While waiting for The World’s End, I watched Shaun of the Dead and Hot Fuzz over and over and over again. They were great films, and they rewarded repeat viewings. I noticed something new or appreciated something more each time. They each retained, on the whole, their ability to surprise. They were — and are — finely crafted little puzzleboxes that allow you to respect the craftsmanship even after you think you’ve learned its secrets.

Then The World’s End arrived. I saw it as early as I could, and never wanted to see it again.

In fact, until this month I didn’t revisit and reassess it at all. Shaun and Hot Fuzz stayed in rotation, but I never felt compelled at all to attempt The Golden Mile again with the court of Gary King. There were a few reasons for that, and only some of them were were conscious. I understand my feelings a little better now, and having seen it a few more times I can say that I enjoy it more than I originally did, but The World’s End is, without question, the weakest of The Blood and Ice Cream trilogy.

Whereas the previous two films were tight, complex constructions of both writing and directing, impressive little gifts that seem to contain more every time you open them, The World’s End is all exposed plumbing.

It’s a mess that begins to unravel partway through the film and never quite stops. Its tonal shifts are abrupt and inelegant. Its echoes are (often) forced and without meaning. And the final half hour(!) is given over to a long-winded explanation of what we’ve just seen, heaping upon us a great deal of new information but failing completely to surprise.

It’s bloated, aimless, and can’t seem to figure out what its own message is.

But you know what?

It’s still better than I gave it credit for being.

And while there’s a lot of fat just begging to be trimmed, there are also some truly great moments that more or less justify the missteps.

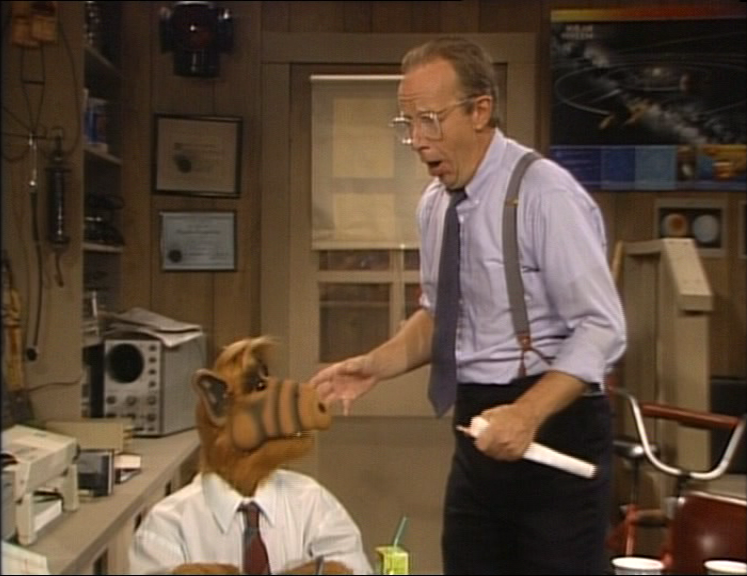

The central conceit this time around is that Pegg’s character, Gary King, rounds up four of his childhood friends for one more crack at The Golden Mile; a 12-pub crawl that they failed to complete back in June of 1990. This necessitates a trip back to Newton Haven, a town each of them was all too happy to escape.

While they’re there some bodysnatcher stuff happens or whatever. I’d explain it here but the voice of Bill Nighy spends 30 minutes doing exactly that and I wouldn’t want to steal his thunder.

The most basic disappointment for me is that The World’s End doesn’t quite manage to mesh its universes. The zombies in Shaun and the slashers of Hot Fuzz felt important to those films, but the bodysnatcher aspect of this film never quite gels with the pub crawl.

In fact, they actively work against each other at several points, and for the first time in the trilogy I started to wish Wright and Pegg just told a straightforward human story without any of that blended-genre silliness.

That, of course, would go entirely against the ethos of the trilogy, but I still feel it would have given us a better film.

The best stuff comes at the beginning of The World’s End, which is incredibly strong. Gary narrates an extended flashback of the fateful night he and his pals attempted The Golden Mile, and a perfect bittersweet note is struck…the nostalgia one eventually feels for times that weren’t that great to begin with.

It’s a great little sequence that strikes an impressive chord. It understands exactly how we reflect on the past and cringe at who we were, wonder how we’re still alive, and yet…still miss it.

The sequence is set to “Summer’s Magic,” a dance track released in 1990 which is both the perfect soundtrack choice and a song whose title and release date are quite meaningful to the film. In fact, the soundtrack overall is something I take no issue with, with most of the songs being period-appropriate, many of them being quite good, and all of them commenting in some interesting way on the action.

Then the flashback ends and we get a legitimately painful contextual surprise: it turns out Gary was narrating his story not to us, but to a support group.

It’s a truly dark twist that in a flash recontextualizes everything we’ve just seen, and, unfortunately, it sets the bar too high for The World’s End to really live up to. Nothing else in the film is anywhere near as clever — or affecting — as that reveal, and that’s a big part of the problem. The support group fakeout hurts. It takes the cheery narration and wistful footage and jaunty soundtrack and slaps it away with a brutal dose of reality.

The rest of the film, however, lacks that kind of twist. It presents itself…and that’s all it does. The masterful undercutting on display in that opening moment is absent for just about everything that follows. The World’s End is a disarmingly superficial film in that sense, made all the more frustrating because it started as a film that was anything but.

There’s no second layer to anything we’re watching.

Granted, Gary King views himself a dashing, irresistible figure…while his friends find him a bothersome nuisance. At no point do we suspect otherwise, though, and at many points the characters outline this precise dichotomy for us. There’s no twist to it and no surprise. Gary sees himself one way, the rest of the world sees him another, and that doesn’t really change. There’s no twist, and no surprise.

Similarly, for much of the film there’s an unspoken trauma in the group’s collective memory, and that seems as though it will pay off in some kind of interesting way, but it never does. I’m referring to the “accident” that caused Gary and Andy Knightley (Nick Frost) to part ways.

We hear only passing references to this event, and it’s indeed an intriguing question. What happened? Gary might miss all of his friends, but it was Andy to whom he was clearly closest. It’s Andy that he misses most.

What exactly came between them? We know it was an accident, but that’s all we know. We want to find out more.

…and so we find out more. And we realize we knew enough already.

It’s revealed that Andy wrecked a vehicle — and was nearly killed — while driving an OD-ing Gary King to the hospital. After the crash Gary scampered away to leave Andy to deal with the fallout. Which, indeed, is pretty shitty, and exactly the sort of thing that would break up a friendship for good.

But does any of that change what we already knew? Do we reconsider anything? Does it change or enrich our understanding of the situation at all?

We know the details now, but there was enough context already (Gary’s hard-partying lifestyle, the fact that there was an accident, Andy’s disinterest in seeing Gary again, Andy’s tee-totaling) that we pretty much had the idea. It’s enough to know that Gary did a shitty thing to Andy; finding out what that shitty thing was fails to register, because it’s completely in keeping with what we’ve already assumed.

Additionally, late in the film, as Andy and Gary are brawling in The World’s End, Andy sees that Gary is wearing a hospital bracelet. (Reading — with a note of masterfully cruel irony — KING GARY.)

But, again, this is something we already knew. It lends a nice bit of retroactive weight to Gary refusing to show his arm in the smokehouse, but it’s something we already knew. We learn everything we need to know about Gary King in the introduction — and everything we need to know about his friends in their introductions — which leaves the film with such little room to surprise.

Having said all of that, the scenes of the group reconnecting are pretty great. The first couple of pubs see the men catching up, realizing how much they’ve changed, and, slowly, slipping back into old jokes and dynamics. Their laughter feels warm and genuine, and they really do come across as people who became adults individually but remember what it was like to be kids together. It’s very well done, and unquestionably well acted.

The feeling of returning to one’s home town is also handled very well. I didn’t grow up in a town like Newton Haven, but the feeling I get from watching the gang revisit it is on par with the feeling I got when I returned home after nearly a decade away.

There’s some melancholy distance that Wright conveys so well I can’t even explain how he does it, the feeling that this was once part of you…and isn’t anymore. The feeling that you couldn’t wait to leave, but now it’s kind of nice to be back…even if you still can’t wait to leave.

The most affecting example of this is when, early in the film, a man who used to bully Peter in school borrows a chair from the gang’s table, and Peter immediately shifts back into feeling like a helpless child. Brilliantly observed is the fact that the most painful thing about his memories is that he’s the only one who has them. His tormentor doesn’t even remember him. All of it — every unforgettable nightmare he endured and the scars he still carries — stayed only with him. To this day, he remains the only one to suffer.

It’s a very realistic scene, and one of the few times in this film that we turn a human lens on someone who isn’t Gary or Andy.

But the reconnecting goes only so far, because there’s another kind of story the film wishes to tell: one about bodysnatching. Unfortunately, it’s one that Wright and Pegg never figured out how to integrate naturally.

Instead of feeling like an organic part of The World’s End, the bodysnatcher plot robs the film of what should have been its most affecting moments, beginning with the scene in which that concept is introduced. Gary failing to impress a younger boy with his hard-drinking plans for the night — something that should register as a sad, aging man unable to cling to a popularity he never had — is rendered meaningless upon the reveal that the boy is an automaton.

It’s even less interesting when compared to a similar scene in Spaced, in which an almost identical exchange happens — right down to it taking place in a restroom — and which manages to feel both more affecting and more menacing. It’s a lesser shade of something we’ve already seen, and it’s lesser because it’s less natural.

And that ends up being the problem all around. Gary is frequently (and temporarily) deflated by the fact that so few people in Newton Haven remember him and his antics, but that means a lot less when it’s revealed that they’re all robotic replacements for the people he did know. So far from having to face the fact that he’s not the living legend he believes himself to be — which would have given his character some sorely needed growth — he gets to assign his lack of notoriety to the fact that these are all robots, and not the people who would remember him.

Part of what makes the film’s introduction work so well is that it spotlights, indirectly, how big the small things can feel to us. How massively important they are to us, while they mean nothing to anybody else.

The events of that night in 1990 meant — and continue to mean — the world to Gary King, but to anyone working at those pubs, drinking alongside the boys, or otherwise going about their business, it was just a night. The kids were just customers.

That’s the awakening Gary King should have…not the assurance that they would remember him if only they hadn’t been replaced by machines.

Then again, the robots (or Blanks) are shown to retain the memories of the people they replace, so I’m not sure where the film wants us to land on that. It’s our explanation for why nobody in Newton Haven remembers them (which seems to be reinforced by the fact that those who haven’t been replaced, such as Mad Basil and The Reverend Green, do remember them), but the twins recognize Sam, and Mr. Shepherd remembers them even though he has been replaced, so I’m not sure there is a definite answer in there.

Even odder is the fact that the Blanks have such radically different responses to the boys. In the first pub, the barman doesn’t recognize any of them and is not interested in engaging with them. In a later pub, much of the dialogue from the first pub is revisited, with the barman (Spaced alum Mark Heap) making a big, friendly show out of recognizing and engaging with them. That’s odd because Heap’s barman is meant to clue you in to the fact that he’s a Blank, as that plot point was recently revealed to the characters. But the first barman was also a Blank; we just didn’t know it yet. So does a Blank want to wall Gary and company off from their pasts, or fool them into thinking they’ve found it again? If they’re meant to represent a unified “Starbucking” (as we’re overtly told they are), then why are their behaviors and intentions at odds?

Maybe it’s a plot inconsistency, or maybe I’m just missing something. Either way, it’s nit-picking I wouldn’t be doing if I didn’t have a larger issue with the bodysnatchers.

So here’s my larger issue with the bodysnatchers: nobody flees.

The film does its best to give us a reason for that.

In fact, it gives us a bunch of reasons because it’s desperate to have us believe that these idiots will still try to finish the pub crawl: the buses have stopped running, there’s nobody sober enough to drive, they don’t have a car, nobody has a better plan, and so on.

All of which is fine. None of which convinces me that they wouldn’t make a break for it anyway.

Running might be a doomed idea, but aside from Gary I see no reason the others wouldn’t at least try…especially considering the fact that they weren’t having all that great of a time to begin with. They were already talking about ditching The Golden Mile and going home back when it was just a dumb social event.

Once they realize their lives are in danger, they for some reason feel less inclined to give it up.

It’s a cheat. A necessary one to keep the film moving, but it’s only necessary because Wright and Pegg came up with lots of reasons the guys would stick together, and none of them are the right one. Gary King, I believe, would march stupidly into danger for the sake of finally completing The Golden Mile. I don’t believe that any of the others would push through as stupidly.

The danger simply isn’t handled believably to me here.

In Shaun of the Dead, Ed and Shaun fled the danger because it wasn’t safe to stay where they were…and they picked up the others because it wasn’t likely to remain safe where they were, either. Right or wrong, the impulse to find a safe place to hole up made sense.

In Hot Fuzz, Angel’s response was the opposite: he tackled the danger head-on, even when he knew he was doomed (see him attempt to place the entire NWA under arrest, alone), but that, too, made sense because of his unwavering commitment to justice. When the police joined him in his crusade, that also had a built-in explanation: they were the police.

In The World’s End, though, the characters’ response to the danger feels forced and manufactured, a product of the fact that the movie needs them to behave that way, and not because that’s who they are.

The bodysnatcher stuff does give the film some great moments, I admit. The scene in which the gang drunkenly tries to figure out what to call them is brilliant, and Gary’s “to err is human…” speech toward the end of the film is one of the best things in the entire trilogy. Ditto Nick Frost’s incredibly cathartic performance when he rips his shirt open and shouts, “I fucking hate this town!”

But overall it just leads to some toothless commentary about Starbucking, and dull (and often humorless) fight scenes.

Shaun of the Dead had the good sense to keep its action either brief or funny. Hot Fuzz leaned on it a bit too hard, but still made Angel’s creative non-lethal takedowns interesting. (And, it must be said, still pretty funny.)

But in The World’s End they just feel tedious. Maybe it’s the silliness of the blue ink or the way limbs pop off and reattach like action figures, but something here just lacks weight, and I lose track of why I’m watching.

The first fight scene in the restroom uses one seemingly unbroken take (I don’t know for sure if it’s genuine or editing-room trickery), which may be technically impressive, but I don’t find it particularly engaging. It seems like something done for the sake of doing it, and not something done because that was the best way to shoot the scene. Compare it to Rope or the Copacabana scene in Goodfellas and you’ll get a sense of how hollow the gesture feels here.

A later brawl sees Gary’s drinking continually interrupted, and that’s decently funny, but otherwise it’s just the characters hitting people and getting hit in return. It gets old quickly and never complicates itself. The fight with the twins comes across as too Looney Tunes to even feel like it’s part of the same film.

In fact, nearly all of the bodysnatcher stuff feels like filler, and that might be because — unlike zombie films and cop movies — bodysnatcher films don’t have an established set of tropes from which to draw.

Both of the preceding installments in the trilogy hinged upon us knowing (at least in passing) the rules of the genres that they straddled. “Bodysnatcher” isn’t really a genre. Sci-Fi sure is, but it’s also much too broad. As a result, we’re left with a movie that doesn’t get to coast on an assumed level of familiarity as the last two did. It needs to introduce — continually — every one of its rules.

And, as a result, it feels like it’s putting forth a great deal of effort just to approach what the other two films achieved so naturally.

But, mainly, there’s the fact that Gary King doesn’t change.

Nobody really changes. There’s an odd, unnatural stasis at the center of The World’s End, and I honestly don’t know how much of it is intentional, or what’s meant by it. It becomes particularly problematic at the end of the film, when Gary’s behavior and attitude (and reluctance to change or grow) results in global apocalypse and countless deaths. (Including his friends and loved ones, his own mother among them.)

What’s more, Gary causes this to happen.

In Shaun of the Dead and Hot Fuzz, the danger springs up with no help from our protagonists. Shaun tries to beat it back; Angel successfully puts a stop to it.

Gary King, by contrast, triggers the apocalypse single-handedly.

And yet, nobody in the film seems to bat an eye. They just adjust to the fact that the planet is a desolate wasteland, and Gary leads younger, robotic versions of his friends from pub to pub.

That would be fine if there were a larger statement being made, but if there is I’d have trouble identifying it. I don’t even know what Gary’s ostensible purpose is, let alone the film’s larger, thematic one.

It’s not to get drunk with his young friends — he orders waters for all of them — and he knows he and his gang aren’t welcome, so I guess it’s just to start fights and be a dick?

It’s an oddly vague conclusion for a film that just spent half an hour trying to rigorously explain to us what we were watching.

You know what, though?

There’s a lot that The World’s End gets exactly right.

As down as I am on it, and as much as I can pick it apart, there is a lot that I enjoy.

There’s the intro sequence, obviously. There’s the series of short scenes of Gary rounding up his old friends, in which Simon Pegg seems to channel a somehow-more-delusional David Brent. But the biggest achievement comes, again, from Nick Frost. He plays Gary’s most pained and hurt companion beautifully.

Andy, if anything, is too real.

His standoffish nature and refusal to engage is just…it’s brutal. It hurts to watch. And it’s not because he turns away from his friends, but because it’s so clearly a symptom of how much he aches on the inside.

He has his life together, but he’s unhappy. And when we learn later that his wife and kids have left him, it lands. It makes sense.

This is a guy who played second banana to someone who literally left him to die…and he scraped his life together as best he could only to have that fall apart as well.

It’s affecting, and it feels real in a way that Gary’s struggle — however we may wish to define that — does not.

Andy has been beaten by life. His inner conflict doesn’t feel manufactured; it feels honest and sad. And when he punches his wedding ring out of a robot’s tummy, we get one of the few times in this film that the bodysnatcher aspect has legitimate resonance.

Ditto his fight with Gary toward the end, when he takes his frustrations out on his traitorous, selfish friend physically. There’s something deeply affecting about that. It’s inner torment made manifest. It’s two men who love each other trying to hurt each other, because that’s what they feel like they should do.

The conflict, sadly, doesn’t last. The floor of The World’s End descends and there’s no resolution to the confrontation between Andy and Gary. We’ve left the film about people, and shifted irreversibly into the film about alien bodysnatcher robot things.

The World’s End doesn’t know how to resolve the fistfight that the entire film has been building toward, so it — quite literally — just drops it.

That’s hugely disappointing, but I was talking about the things I liked, so let me shift tracks and say that I also love Paddy Considine’s turn as Steven Prince.

Steven is Gary’s put-upon and downplayed third banana, and he reconnects with his childhood crush Sam. Together they kindle a gentle romance as civilization comes crashing down, and while the romantic element if the film is far from one of its most important, it’s handled very well. Considine does fantastic work here, and I’m glad we got to see more of him after his great — but too-brief — turn as one of Sandford’s detectives in Hot Fuzz.

In fact, the casting is great all around, and the effects work is good as well…even if I do wish the film leaned on it a bit less.

But rewatching it (a few times) prior to writing this, I realized why I didn’t want to rewatch it at all.

At first, I just thought I didn’t like it as much. It wasn’t as funny. That kind of thing.

Instead, I think it’s just a little too hard to face.

Gary King’s arrested adolescence is too well drawn. It’s too potent a reminder of…well, of all the stupid things I’ve done. All the crap I’ve put people through. All the times I hurt someone close to me, and never took the time to apologize or make amends.

I don’t look at The World’s End and see myself. But I do look at it and find unpleasant emotions triggered. See reflections of things I’d prefer not to remember. Realize that even now I’m not the person I probably should be.

That’s not the film’s fault. In fact, I admire how successfully it conjures those emotions.

It’s just frustrating that it doesn’t then know what to do with them.

The World’s End, through my personal filter, starts to look to me less like a bodysnatcher film and becomes more of a psychological horror.

The idea that someone like Gary King could exist…could continue to exist, as he is…could round up his old friends and interfere with their lives all over again…could end the film just as he always was, without the help he needs…could be left bounding unchecked through the world with no incentive to reconsider his place in it…

That’s terrifying to me.

If monster movies have you checking under the bed, this film makes me dread looking in the mirror, lest I see any part of Gary King staring back at me.

It paints a man like Gary very well, and then doesn’t know what to do with him. The character — and the audience — are underserved.

If anything, the film’s biggest problem is how accurately and honestly it paints Gary. Because he’s not a caricature, and is instead a deeply hurting and dangerous man, he’s beyond the scope of the film. He’s too much for it to tame. He, by his own existence, raises questions and triggers concerns that the film isn’t capable of addressing.

But because it paints him so effectively, it can’t be a bad film. It’s disappointing, especially in light of the two that preceded it, but The World’s End hits some great notes along the way. It has interesting things to say about growing up, even if it can’t quite complete the thought.

And again, at its core, it’s the story of Pegg’s and Frost’s characters. This time around, though, it’s not about why they need each other. In fact, they don’t need each other at all, and they separate at some point before the end of the film to do…whatever it is they each do.

The emptiness of the ending comes from the confused story the film is trying to tell. Perhaps it was too ambitious for its own good. Or perhaps Wright and Pegg just got complacent. I certainly don’t know, and I can’t pretend to.

But I know that it’s worth watching, even a few times, because the lousy stuff makes you appreciate the previous films a bit more, and the good stuff is really good stuff.

It’s just that, for the first time, the balance seemed to really falter.

That’s at least in keeping with the film, though.

You can get the old crew back together, but you’ll never manage precisely the same magic.

All you can ask is that you get some enjoyment out of it, before it’s all over.

Happy Halloween, everyone. Thanks for reading.