I like junk.

I really do. I like terrible movies and television shows and music and video games. While I have less patience for them overall, I even like some bad novels.

What I’d like to convey by saying this is the fact that I don’t mind turning over some sliver of my life to a piece of art that, by all accounts, doesn’t deserve it. I actually enjoy that. There’s a giddy thrill that comes from watching the wheels fall off. That comes from the complete breakdown of what should be an elegant machine. That comes from watching a pile of disparate components continuously fail to connect.

I like bad things. You’ve seen me gush about many of them here, and when I worked for Nintendo Life, I earned a reputation for it. When a seemingly bad game came along, it was assigned to me almost without fail. This is both because they knew I’d find enjoyment with it when most others couldn’t, but also because they could count on me to engage with it respectfully. To dig through the muck in search of something worth talking about. Often, I found only more muck. But sometimes I’d find merit where nobody expected it, and I’d get to show that off to the skeptics. That, to me, made it worth the investment of my time and attentions.

I think the appeal of failed art is an instructive one. Many of my friends don’t have the interest or patience required to watch a movie they know will be a wreck, and I understand that. But my creative friends — the ones who write, or paint, or compose, or make films of their own — are the ones that do enjoy it. Oddly, the more invested you are in producing works you can be proud of, the more interested you are in observing failure.

That’s not a negative impulse, necessarily. While sniping criticism can come from a place of nastiness, I hope mine never does. I hope it comes, rather, from the active desire to analyze, forensically, what went wrong. To, yes, laugh at the sillier missteps, but also to think critically about art. About the missing connections, the faulty components, the same decisions that worked in one place being embarrassing elsewhere. About, as one of rock’s finest musicians once put it, the fine line between stupid and clever.

It’s fun to pull these things apart, but it’s also creatively important to do so. Like literal autopsies, dissecting these corpses gives us a better understanding of what happened — or failed to happen — and can help us, as creators ourselves, to avoid similar fates for our works. And, of course, they help us to appreciate the art that does work…the films that surprise, the novels that move, the music that changes who we are, the video games that make the mechanical press of a button feel like an urgent and compelling adventure.

All of this is to say that I like junk.

And I still don’t like Mega Man 6.

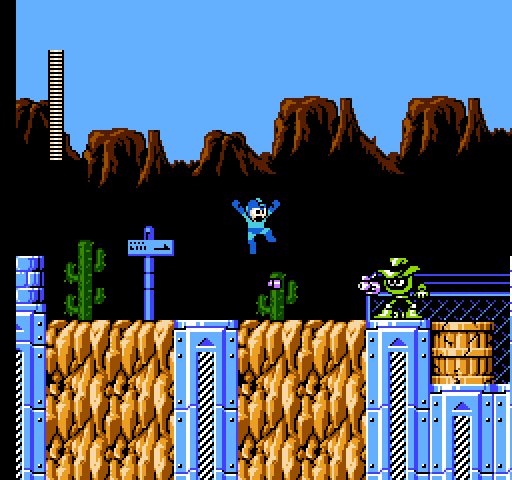

Mega Man 6 is a bad game. It’s not just bad by Mega Man standards; it’s a fairly lousy experience even removed from comparison with its five far superior predecessors.

It’s not a fun kind of bad. There’s nothing worth a chuckle, no heady “Did that really just happen?” moments, and no especially interesting creative missteps worth untangling. (We’d have to wait another two games for that.)

In short, Mega Man 6 isn’t The Room. Instead, it’s more like a dull documentary about a subject of no interest to anybody. And that’s the problem. The issue isn’t that Mega Man 6 is bad…the issue is that it allows itself to be boring. Perhaps, rightly, the cardinal sin of gaming.

It’s also the first Mega Man game I didn’t play on release. I knowingly let this one pass me by. While it’s tempting, then, to dismiss my dislike of the game because I merely lack nostalgia for it, I can promise you that’s not the reason. I didn’t play Mega Man 7 on release, either, but in the next installment you’ll see that I have a lot of nice things to say about it.

No, I don’t dislike Mega Man 6 because I can’t don my rosy spectacles. I dislike it because it’s kinda awful.

I remember when it came out. I was still an avid reader of Nintendo Power, and I saw it advertised there. And, for the first time, I didn’t have any interest in playing a Mega Man game.

I don’t remember enough about its coverage in that magazine to say why, but I do remember looking over the slate of new Robot Masters and feeling…nothing.

Had I outgrown the series? Maybe. We let go of childish things, and year by year our definition of “childish” evolves. Maybe the promise of guiding Mega Man through another eight duels just felt…beneath me. Then again, I was 13 when this was released, so it’s not like I had much concept of intellectual stimulation.

It may have been different in the game’s native Japan, but I don’t think there were many American children who took a look at an enemy roster that contained Yamato Man and thought, “Yes, I need to play this.”

I also remember seeing an image of this game’s central villain, Mr. X. And, to be totally frank, that made the game feel even lazier than a sixth installment should have felt. The previous two games already pulled the same trick…leading us to believe that Wily wasn’t behind the chaos, only to reveal that, yes, he was. Those games, though, at least tried to give us a relatively convincing decoy: Dr. Cossack and Proto Man, either of whom, for all we knew, could have been the bad guy.

Mega Man 6 attempts the same shtick for the third time running, and isn’t convincing at all. Mr. X is very clearly Dr. Wily in Groucho glasses. It was embarrassing, even when I was much younger, to look at a piece of promotional art and immediately figure out the game’s big surprise.

I was a dumb kid. If I figured it out, you had a dumb twist.

And so the game didn’t really look like it was trying very hard. I didn’t feel compelled to try any harder. I let it pass.

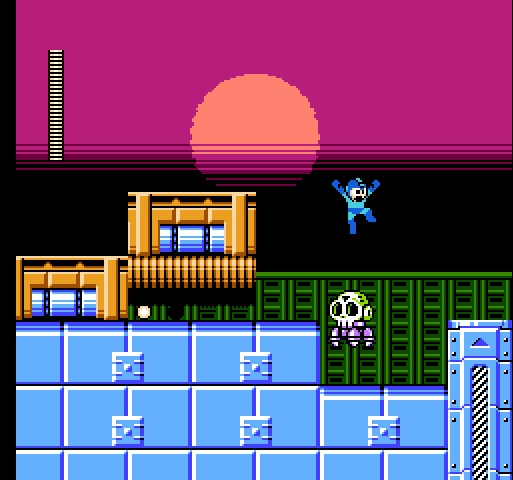

Additionally, I think I had a lack of interest in the game for the same reason many others did: the Super Nintendo had already been out for three years by the time we got this game. Just about anyone with an interest in the medium had long moved on from the NES, and the sixth installment of a decidedly rigid franchise wasn’t about to bring us back.

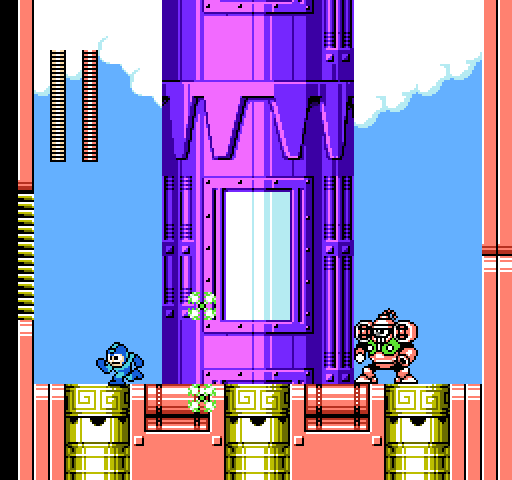

More to the point, Mega Man had moved on, as well. Mega Man 6 was released in North America two months after Mega Man X.* Anyone who really cared about the blue bomber had a whole new series to look forward to, and was already dug into a much more complex, more interesting, better designed, better looking, more fun game.

No, it didn’t star the same character, but it was recognizably the successor to the NES games we knew and loved. Only now it had evolved, like so many other great series, sending the same shivers down fans’ spines that they got from Super Mario World, A Link to the Past, Super Metroid, Super Castlevania IV, and more.

Mega Man X represented the future. Mega Man 6 represented the stubborn and unwelcome past. Place the two games side by side, and there’s a very clear winner.

But that was then. We overlooked Mega Man 6 and didn’t feel as though we were missing anything. So what? We grow up. We start deliberately looking backward. We reappraise the things we loved and the things we didn’t.

We can dig up what we missed, and spend time with it. Turn ourselves over to it. Consider it not as the sixth game in a series or the immediately outdated competitor to another. We can look at it as a self-contained experience.

And we should.

Because that’s how we can be confident in concluding that it really is lousy.

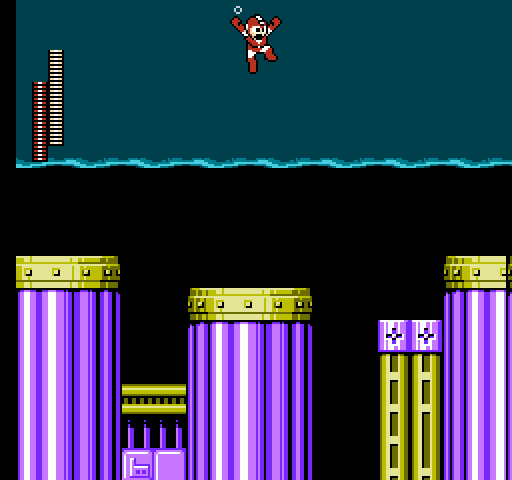

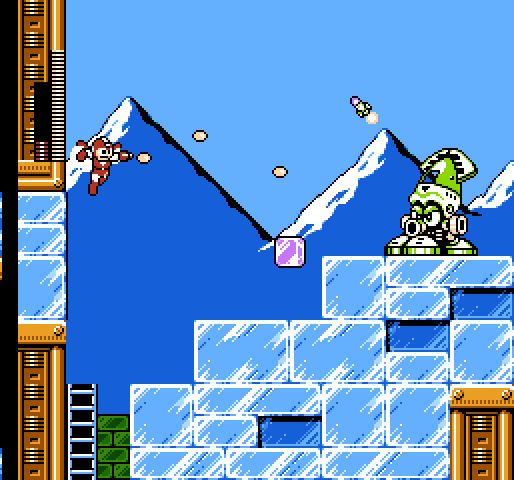

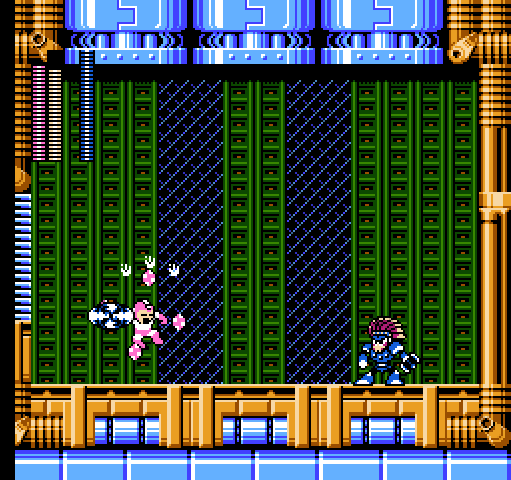

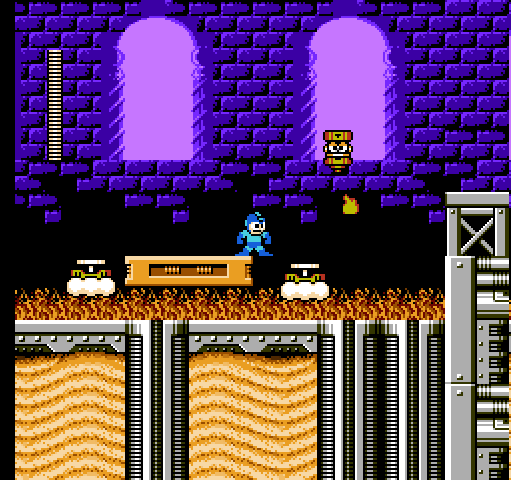

On the surface, it just looks like a basic — if uninspired — Mega Man game. Eight bosses to tackle in any sequence, each holding one of eight new weapons to collect. Mega Man can hop, shoot, slide, and charge his Buster. We earn new transformations for Rush. We then fight through a false castle, the real castle, and reduce Wily to pleading for his life.

That’s what we expect from a Mega Man game at this point in the series and, superficially, Mega Man 6 meets those expectations.

But that’s not all we expect.

We also expect some tweak to or enhancement of the formula. As much guff as Mega Man gets for being the same game 10-odd times over, the truth is that it’s always changing. Mega Man might have hit upon a sturdy and winning formula right out of the gate, but every game that followed brought something new, something that defined not only that game, but went on to inform the design philosophy of the games that followed.

These changes took many forms, be they the number of Robot Masters, additions to Mega Man’s moveset, the introduction of a supporting character, scattered collectibles with a reward for finding them all, or anything else along those lines.

In short, Mega Man never saw a substantial overhaul of its formula, but it never stopped questioning what it could do within that formula.

Well, I say never…

Flatly, it stopped with Mega Man 6. There’s nothing new here. At least, not in terms of advancements or refinements. It represents several steps backward — as we’ll discuss — but in terms of doing anything unique with the series…it just feels uninterested. It’s the first Mega Man game content to say “We don’t need to do anything new here,” and that goes a long way toward making it feel lazy and uninspired.

There are a few slight flourishes unique to Mega Man 6, and we’ll discuss those as well because they’re part of the problem, but none of them feel like complete thoughts. They’re just…there, and they were discarded by the games that followed, rather than incorporated into the series’ DNA.

Actually, I take back what I said a moment ago. The series didn’t stop toying with its formula with Mega Man 6. Instead, it stopped during Mega Man 6. Mega Man 7 bounced right back with new ideas that carried through the rest of the series, such as splitting the Robot Masters into two groups of four, adding isolated introduction and midpoint stages, and introducing a currency system. And Auto. And Bass…

With this in mind, Mega Man 6 is not revealed as the point at which the series stopped trying…it’s just the game that stopped trying.

But, okay, fine. It’s disappointing to play a Mega Man game that brings nothing new to the table, but what about the experience of playing it? Surely if it’s fun enough on its own merits, we can overlook the fact that we’ve seen all of its tricks before.

And, yes, I’d agree with that entirely. But Mega Man 6 isn’t fun. It had the luxury of relying entirely on what the series does well without having to spin new plates, but it’s a luxury the game squanders by doing nearly everything worse.

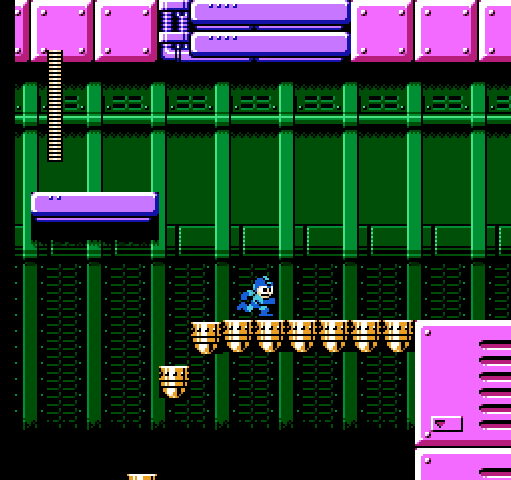

To take the most basic — and necessary — example, there’s the controls.

You’ve probably noticed by now that I’ll sometimes bring up points about one game while I’m talking about another. That will happen, though, if I feel a later game provides a more natural place to raise the concern, so forgive me for doubling back and saying that one of my issues with Mega Man 3 is that it has a habit of eating my inputs.

This may be related to the game’s issues with lag; perhaps the code struggles so much to keep up with itself that when I press a button, it doesn’t bother even trying to respond to my request. It’s doing all it can just to hold itself together; why should it tax itself even further by letting me do clearly unnecessary things, such as jump or fire?

Usually this happens when I try to do multiple things quickly.

For example, I fight Hard Man with a series of fairly rapid button presses. I’ll run away from him, toward the wall. I leap his first projectile while still running away, turn quickly to face him, fire off a shot, and turn again, quickly, back toward the wall. Then I repeat this for his second projectile. I’m not trying to pat myself on the back for agility, here, but rather to illustrate the kinds of situations in which Mega Man 3 ignores one or two of my inputs. Sometimes I’m sure I pressed B, but Mega Man doesn’t fire, and I suspect that’s because I’m feeding the game so much movement to keep track of that it loses other commands while juggling them.

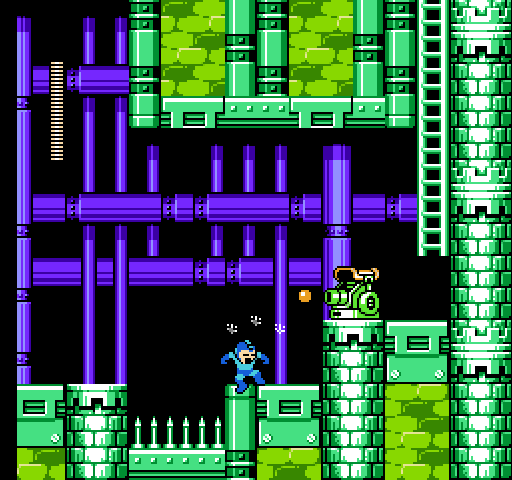

Mega Man 6 takes eaten inputs to a whole new — and wholly inexcusable — level. Instead of fast, nimble movements, I’ll stroll simply through each of Mega Man 6‘s stages and still find that it won’t let me jump, fire, or slide when I ask it to. Nothing much is happening on screen; I just want to slide to get away from a stray bullet, and Mega Man won’t do it. I just want to shoot at this enemy standing in my path, and though I hammer the B button, he doesn’t shoot. I just want to hop over this pit instead of walking mindlessly into it, and though I can hear the press of the A button, the game ignores my input and I die.

The highest failure rate seems to come from sliding, which just doesn’t feel responsive at all. Why the most fluid of all of Mega Man’s movements — one which for the previous three games posed no problems whatsoever and was a natural, organic delight to use — feels so clunky and unresponsive here is beyond me. Clearly the developers toyed around with whatever code informs Mega Man’s mobility, but whatever improvements they were making — such as his increased speed on ladders — were not worth breaking his evasive functionality.

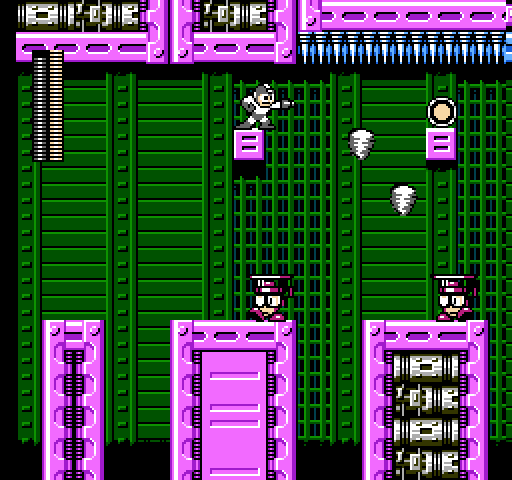

Mega Man is a series that encourages and rewards perfection. Every screen is a puzzle, with each platform, obstacle, and enemy a piece to be properly fit together. It’s a knowingly difficult experience, one that punishes players for barrelling brainlessly forward by ensuring that they’ll get nowhere until they start engaging with the game respectfully and intelligently. (I know this for a fact, as I spent my first few years with the series playing brainlessly and getting nowhere.)

Mega Man’s health bar is long and generous, but act like a boob and Mega Man feels hopelessly fragile. Take your time, learn from what the game teaches you, and employ critical thinking against even the smallest enemies, though, and you’re suddenly empowered. The health bar is more like a meter of the game’s patience; exhaust it and the game steps in and forces you to try again.

That’s why bosses (almost always) have exactly the same health bar you do. It’s an inherently fair matchup. You each have a bit of leeway when it comes to making mistakes, but who will make more of them? You or your adversary? Who will be tricked into making the final, fatal one?

I say this to emphasize the necessity of Mega Man’s tight evasion. In the first two games, it was simply a matter of walking to the side or jumping. That was all you could do in order to avoid collision with an enemy or a projectile, and that was fair, because the games were designed with that limited moveset in mind. Mega Man 3 introduced the graceful slide, and from that point forward the games took that into account as well. If you could slide, after all, why not present you with enemies and hazards that either required or strongly favored sliding as evasive action?

Mega Man 6 cripples the responsiveness of that evasive action, and, in doing so, turns the game into the unfairly punishing, arduous slog that the series’ detractors always claimed it was. It recontextualized the health bar not as a meter of the game’s patience or a gauge of how many mistakes you can make before being rocketed back to a checkpoint…but as an actual bar of health, and one that depletes by some degree every time the game refuses to listen to what you say.

Mega Man 6 is the first game in the series that demands perfection without actually providing the responsiveness that allows it.

Another step backward comes with the soundtrack. Not that it’s bad. In fact, it’s quite good, and contains some of the best compositions Robot Masters have ever had. The problem, rather, is that they aren’t fitting of the series.

It’s a bit difficult to explain what I mean, but I think a lot of people play Mega Man 6 for the first time and come away feeling that the music kinda sucks. That was my opinion for sure, and it held for a long time. Only later did I realize how rich and layered these songs are, and I think if more people gave the songs a proper listen, they’d agree.

But when we play a game in the Mega Man series, we can’t afford to devote our conscious attention to the soundtrack. Previous games — Mega Man 2 and Mega Man 3 in particular — are revered for their soundtracks, and it’s because the hook in each song is both immediate and repetitive, with the pulse of the composition steady and strong enough that we hear it — and absorb it — while we’re focusing on something else. It’s great music, but it’s composed as great background music.

That’s why you can recognize almost any Mega Man song from a clip of just a few seconds in length; they’re written that way. The composers and designers both understood that the song had to make an impact whenever it could. Perhaps that was for the first few seconds at the beginning of a level. Perhaps it’s in a moment of calmness between two firefights. A player’s attention will be fixed almost anywhere but on the soundtrack, so the soundtrack needs to work whenever it does get attention.

Mega Man songs need to be tight and punchy, full of energy or at the very least atmosphere. (The best songs are both.) They need to say everything they want to say in the space of a few seconds, and yet also be conducive to endless looping. It’s not an easy compositional task, but the previous games understood this and pulled it off.

The compositional philosophy of Mega Man 6, though, is to go with longer songs without obvious hooks, which take their time to build into something interesting. If you’re listening to it on an iPod, it’s pretty good. If you’re playing the actual game, however, you’re too busy staying alive for it to register. You can’t focus on swells and climaxes, and you certainly don’t appreciate the quiet ramping up before we ever get to the melody.

The latter is especially a problem in a death-heavy series like Mega Man. When you die frequently and quickly, as all players picking up this game for the first time are bound to, you’ll hear the song start over before it ever gets going. A song that opens with a slow stretch of its digital instruments “warming up,” such as Centaur Man’s or Flame Man’s, won’t ever feel like a Mega Man track because the player won’t live long enough to hear it become one.

The compositions are of a high quality, but they don’t feel at home in a game with this kind of hectic pace. People remember it as being a bad soundtrack which, truth be told, isn’t miles away from the truth that it’s the wrong soundtrack.

Then, of course, there are the special weapons, which have been on a ceaseless decline in quality since Mega Man 2. Mega Man 6 does a great job of kicking the bottom out of the barrel.

I’m speaking mainly in terms of creativity, as any weapon can be powerful or weak as a game developer dictates. If a cool sword does almost no damage to enemies, it stinks. If a helium balloon knocks baddies out with one shot, it’s good. So rather than focus on how much damage a weapon does or fails to do, I’m more curious about the innovation and imagination that goes into its design.

The weapons here range from unapologetic repeats to just passable. The first of the repeats is the Yamato Spear, which is the Needle Cannon without the ability to rapid fire…the only good thing that weapon had going for it. Then there’s the Plant Barrier, which, as the name implies, is the Skull Barrier with plants where once there were skulls. Swords into ploughshares, and all. Nature from desolation. Thematically worth an essay or two but never worth using in the actual game.

The other is the Wind Storm, which is the Bubble Lead with a different sprite. Sure, when it kills an enemy it sends them irrelevantly skyward, but aside from that it’s the Bubble Lead.

The utter crapness of that weapon is emphasized by the fact that Wind Man — the Robot Master from whom you collect it — doesn’t even use it himself. He instead tries to pull you into his blades, crash into you, and shred you with little propellers. Anything to avoid having to whip out the Wind Storm, I guess. I couldn’t blame the guy if he just started spitting on you.**

The Knight Crusher and Silver Tomahawk are just projectiles with artificially limited range. The former turns and comes back to you like a slow boomerang, and the latter flies largely horizontally and then curves sharply upward. The Silver Tomahawk is therefore good — though not great — for hitting stubborn enemies that like to stay out of your normal range of fire. (Also, by silver they meant brown.) This feeds directly into the design and patterns of one of the fortress bosses, which is nice. The functionality of the special weapons should inform the design of those later stages for sure, but more frequently, as we discussed last time, they feel like they were developed by entirely different teams who didn’t interact.

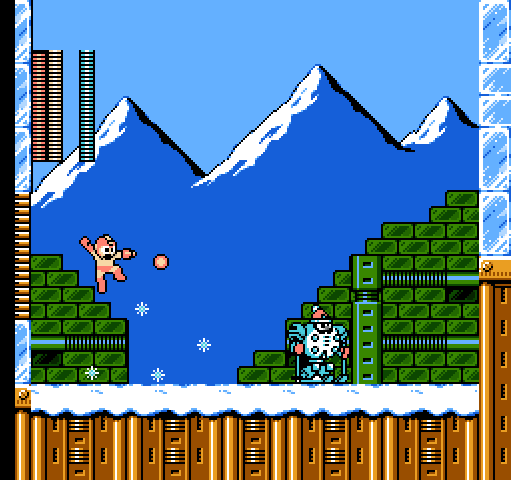

The Blizzard Attack is decently interesting. It places four snowflakes ahead of Mega Man, which, after a moment, spread out and travel forward. They’re decently powerful for snowflakes, though I wouldn’t say they’re fun to use.

The Flame Blast is probably the most interesting, as it’s a heavy glob of fire that falls and forms a rising column of flame from the impact point. Nearly always that means it rises vertically from the floor, but if you hit a wall with it instead, the column will extend horizontally. This is a really cool feature of the weapon that should allow for interesting applications. Needless to say, it’s never explored at all, and it functions as merely another differently shaped projectile. What’s more, if the Flame Blast is fired into an enemy directly it just deals damage and disappears, meaning we lose the possibility of playing with a continuous “burn” effect for powerful foes. That’s a huge missed opportunity.

Before we talk about the Centaur Flash, I want to double back a bit. Despite what I said earlier, Mega Man 6 did actually introduce one new idea that the series kept around. Read on to see why I’m not giving the game any credit for it.

Mega Man 6 introduced weapon demonstrations to the console series.*** This is a great idea, as it allows players to see what these fun new tools do without having to waste precious weapon energy. I love it, but it’s also not really a gameplay innovation so much as it is a very basic and brief cutscene. It’s also not nearly as helpful as it sounds, which is the main problem.

See, later games would include enemies in these demonstrations, so that you could actually see what the weapons do. All Mega Man 6 shows you is how they look, which is pretty useless. Mega Man collects a new weapon, fires it into the void, and off you go. It’s…pretty disappointing.

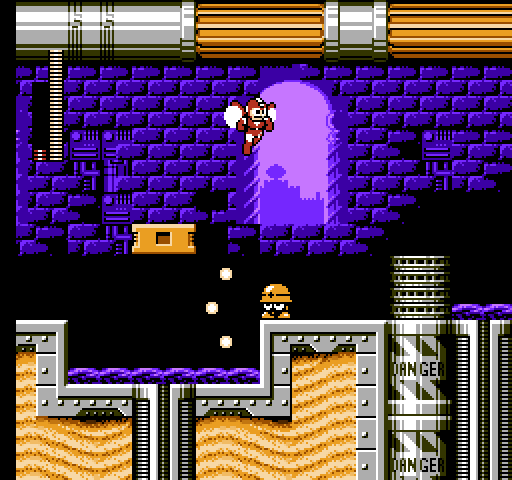

And also frustrating, as we see when we get the Centaur Flash.

Most special weapons, after all, are versions of the weapons we’ve already seen that Robot Master use. As such, you’d expect the Centaur Flash to function similarly to the way it does for Centaur Man himself: we hear it activate, the screen flashes briefly, and Mega Man is frozen in place. So the Centaur Flash is a simple time stopper weapon, right? The series has a precedent for it, and the weapon demonstration just shows the screen blinking when Mega Man uses it, with no projectile or other attack to follow, so that must be what it is.

Then you use it, and find out it’s actually a screen clearance weapon, like the Gravity Hold.

Why? That’s not how it works for Centaur Man. He has a time stopper, not a screen clearance weapon. Yet we get a screen clearance weapon and not a time stopper. That’s confusing, and a perfect opportunity for the weapon demonstration to let us know that what we got works differently from what we saw. It instead tells us nothing.

Even more confusing is the fact that the Centaur Flash does function as a time stopper…briefly. It freezes enemies in place for a fraction of a second as it deals damage. You can’t actually do anything to them while they’re frozen, but it does happen, further confusing me as to why it’s clearing the screen. In fact, I’d assume the logic behind making it Wind Man’s weakness is that it stops his fanblades from turning. At least, that’s the only rationale I can come up with, and it only works if the fucking thing stops time.

Speaking of boss weaknesses — and by no means speaking of Mega Man 6 only — the confusing lack of clear reasoning in these weakness chains creates player detachment and works against the satisfying rock/paper/scissor simplicity of the first two games.

At first, the weakness order made sense. The Rolling Cutter killed Elec Man because it severed his wires; the Thunder Beam killed Ice Man because water conducts electricity; the Ice Slasher killed Fire Man because it melted and extinguished his flame; the Fire Storm killed Bomb Man because it detonated him; the Hyper Bomb killed Guts Man because blowing up rocks is literally what they’re designed to do in-universe; and the Super Arm kills Cut Man because rock crushes scissors.

Mega Man 2 requires a bit more creative thought, but most of the weaknesses make sense. Wood Man, as a tree, can either be burned or cut down. Heat Man can be doused. Quick Man can’t tolerate sitting still. Air Man can be stuffed with leaves to clog up his fan. Even the big question about why the Wily alien is weak to Bubble Lead never confused me the way it seems to confuse others: when you beat the game you see he was just controlling a flying projector; the water shorts it out.

These things make sense. They’re never explicit in-game, but they’re also no kind of barrier to engagement. Maybe you didn’t know what weapon Crash Man was weak to, but once you find out, you can rationalize it. It feels like you solved a puzzle. Indeed, once you get a new weapon for the first time, you can take a look at that stage select and try to guess who might be weak to it. If you’re right, you’ll feel satisfied. As you should.

Then we ended up with tops being weak to knuckles. Toads being weak to drills. Trains being weak to rocks. And we no longer feel satisfied. The weaknesses feel like they were chosen carelessly. The fun of sorting out a logic puzzle — even if you do it after you know the solution — is replaced by remembering that stars are unnaturally weak to water. There’s a distance there. Enjoyment suffers.

Mega Man 6 has a few fair weaknesses — fire melts snow; snow is bad for plants — but that’s it. The bosses in the game seem like they’re weak to things not because they should be by any stretch of the imagination, but because they had to be.

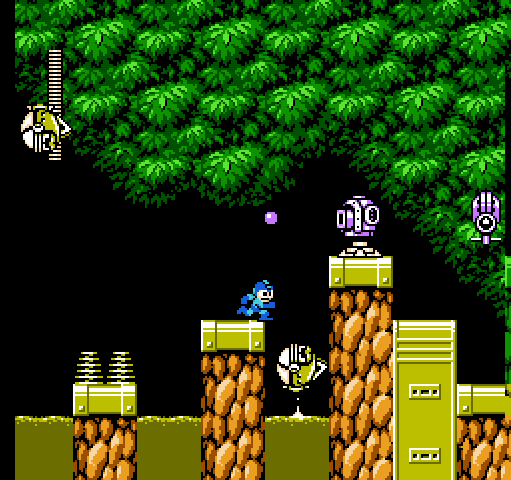

There are things I like about the game, though. Admittedly, they aren’t the things I think of when Mega Man 6 comes up in conversation, but at gunpoint I’d be able to say a nice thing or two.

In addition to the few bright spots I’ve mentioned above, Mega Man 6 has branching paths. As in, proper ones. Mega Man 4 and Mega Man 5 both had optional rooms, but they rarely provided anything more worthwhile than a visit from Eddie. This is especially disappointing in the latter case, as only one of its eight collectible letters was hidden in an optional room, in Stone Man’s stage. In fact, that’s the only letter that was hidden at all.

Granted, snagging many of the letters involved problem solving on the part of the player, which added a nice — if small — wrinkle to the standard, expected gameplay. One had to bravely time a jump from a platform after it had already started to fall in Gyro Man’s stage. In Wave Man’s stage you had to have reflexes quick enough to jump into it during an autoscrolling section. In Napalm Man’s stage you had to find and navigate a short series of false walls. In Gravity Man’s stage, you had to understand the gimmick enough to know how you’d fall during a gravity switch.

All of which is fine, but I think there was a missed opportunity in not hiding more of them out of view, requiring players to seek out breakable walls, small gaps leading into hidden rooms, and paths that were not immediately obvious. Possibly Mega Man 5 just didn’t think its players would be savvy enough to identify alternate paths. Mega Man 6, though, trusts them enough.

And that’s great!

…except that the alternate paths are — say it with me now — handled quite poorly.

In fact, the alternate paths just lead to different versions of the same boss.

The alternate paths exist in four stages. If you play through the stage normally, you’ll make it to the fake boss. You won’t know this, however, because the fake Robot Master looks and behaves identically to the real one. You’ll even get his weapon after beating him.

You won’t, however, get one of the four Beat parts, which allow you to call in your little blue avian friend for help. If you want those, you’ll need to use a utility to find the secret path, which you may or may not ever suspect exists. Find the path and you’re led to…the same boss. Only it’s the real one this time, because he gives you the Beat parts.

It’s a lousy implementation of an otherwise smart idea. Why not encourage the player to traverse a stage multiple times with branching paths? Well, Mega Man 6 answers that rhetorical question: because the path leads to another fight with the same damned boss. Nothing changes in terms of their attacks, their patterns, or their power.

I think the only stage in the game to truly employ branching well is Yamato Man’s, as it contains two parallel paths that are long and offer distinct experiences, right down to a miniboss you’ll encounter on one route and not the other.

Of course, tee hee, that’s not the choice that matters. Later the stage branches again, and this time it leads you to either the real or false Yamato Man. Leave it Mega Man 6 to handle the thing that doesn’t matter well, and the thing that does matter poorly.

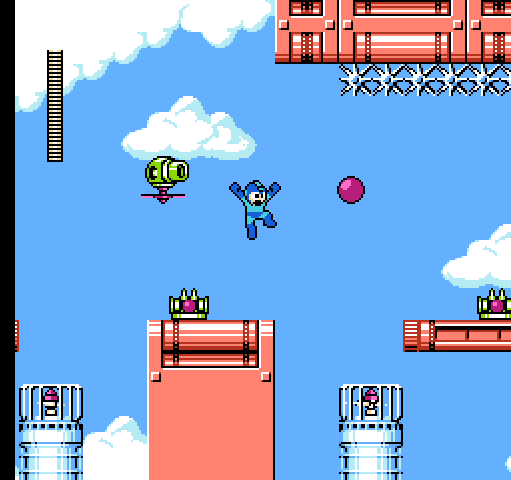

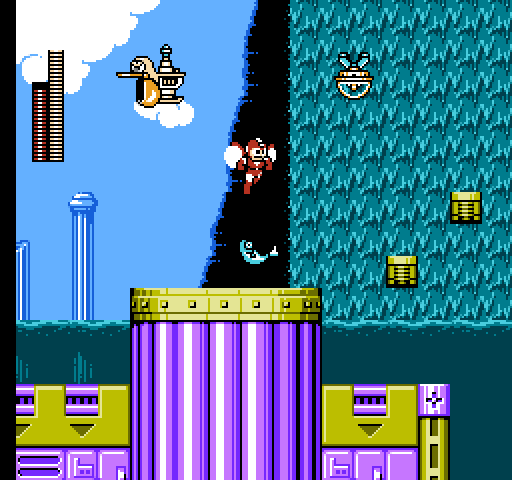

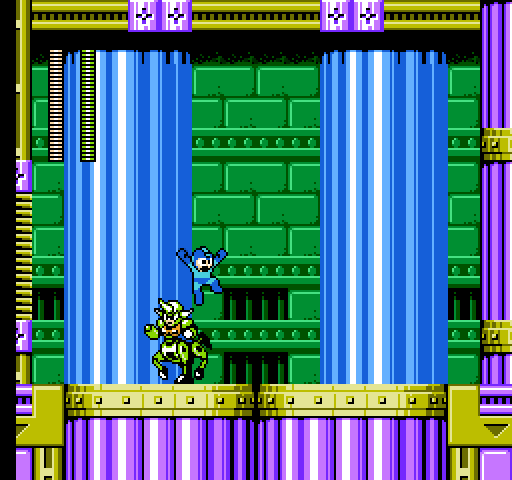

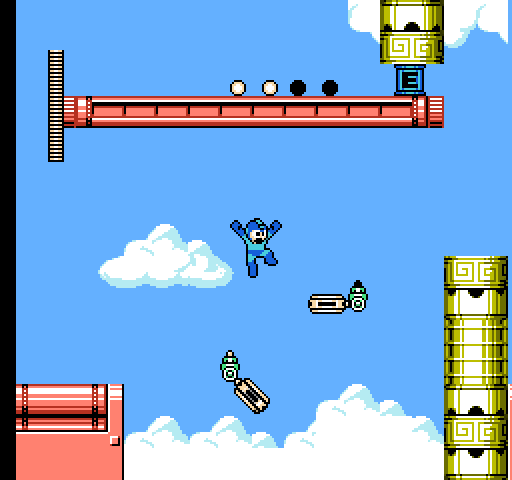

And, hey, speaking of things Mega Man 6 does poorly, there’s the game’s approach to utilities. This time around there are only two, which is fine as nobody was clamoring for a triumphant return of Rush Marine. However, this time Rush doesn’t function as a series of external platforms. Rather he attaches to Mega Man as a sort of add-on, providing abilities and movement options that our hero doesn’t have on his own.

That doesn’t sound bad at all, and it’s an interesting impulse to reconfigure Rush’s role in the games. Again…Mega Man 6 handles it poorly.

The main problem is that switching to Rush adaptors is tedious and breaks the flow. You have to go to the weapons menu, select the adaptor, and then watch a cutscene in which Mega Man and Rush join forces. It’s skippable, thankfully, but you still have to wait for the cutscene to start before you can back out of it.

At first, it’s not much of an inconvenience, but before long — and with the frequency with which you might want to use those adaptors — the extra time eaten up by the process interrupts the pace of the game. In fact, I often don’t bother using them simply because of how irritating the interruption is. It’s as though the developers sat down and actively brainstormed ways to make using Rush less fun.

One adaptor allows Mega Man to fly short distances, and the other allows him to unleash a powerful punch. Neither of them allows him to slide, however, which prevents any sane player from leaving an adaptor equipped for longer than necessary.

Interestingly, the Rush adaptors feel a lot more like they belong in the new Mega Man X series than the classic series. The Mega Man X games also allow the player to find pieces of armor that enhance movement and attack capabilities, and those indeed function as that series’ equivalent of utilities. The classic Mega Man series tends to enhance the hero’s movement by external means. It’s Mega Man X and Mega Man 6 that snap the upgrades right onto the character himself.

That may be a case of parallel invention, or maybe the developers saw what was happening with Mega Man X and found themselves inspired…consciously or not.

But the inspiration — wherever it came from, however deeply it ran — simply isn’t felt in the final product that is Mega Man 6.

It’s not fun. It’s not exciting. It’s just there.

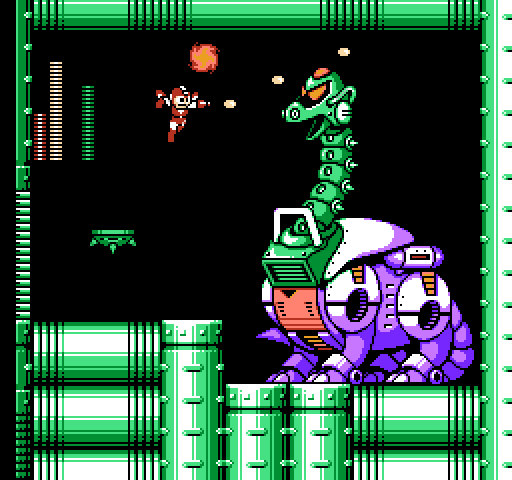

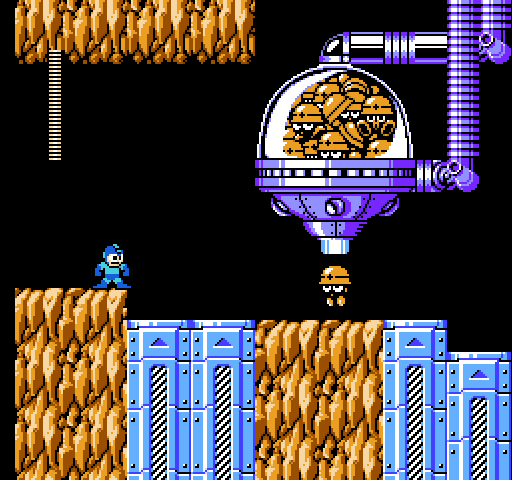

But, as much as I love the series, maybe that wasn’t this game’s fault. Maybe it was just the latest point on a downward creative slide. After all, wasn’t the feeling of spectacle that defined the first few games long gone? We talked a lot about the thrill of seeing the Yellow Devil and the Mecha Dragon for the first time. Did anything else ever live up to that? Maybe Gamma, for some. Beyond that…weren’t these just games?

Good games, sure. Fun games. Maybe even games we loved.

But wasn’t the thrill gone? Weren’t we just going through the motions, just like the series was?

Mega Man 6 maybe just stopped pretending. It knew what we expected, and it gave us that. It went no further than it had to go in order to meet the bare minimum. Why would it push further? The world had turned. There was a new console in town. Hell, there was a whole new incarnation of Mega Man.

Mega Man 6 played to a diminished audience. One that had already moved on. It had a job to do, and it did it. Then it turned the lights out on the NES without bothering to say goodbye. To paraphrase one celebrity oceanographer, Mega Man was hoping to go out in a flash of blazes, and it ended up just going home.

In Mega Man 6, I’d probably say that my favorite Robot Master is Yamato Man after all. I’m not sure why. I think something about him just suggests a kind of nobility, which is the same reason I like Shade Man and Sword Man from some other often-dismissed games.

During the battle with Yamato Man, he’ll hurl his Yamato Spear at you. Whether the shot connects or not, he’ll then run across the screen to retrieve it. He doesn’t attack on the way. He leaves himself wide open. And he knows he does. He knows he’s vulnerable. But he also knows he needs to find and collect it, because it’s meaningful to him.

When you get the Yamato Spear, however, it’s just a projectile to be fired away without thought. You never have to run over and pick it up again. It’s disposable. Removed from its original context, from its original novelty and identity, it’s just a thing.

And that’s Mega Man 6 as a whole.

The series began its life on the NES feeling precious. Important. Irreplaceable.

And it ended its time on the system feeling predictable. Outdated. Forgettable.

You each hold the Yamato Spear, but you do so at very different times in its career.

Best Robot Master: Yamato Man

Best Stage: Centaur Man

Best Weapon: Flame Blast

Best Theme: Yamato Man

Overall Ranking: 2 > 5 > 4 > 3 > 1 > 6

(All screenshots courtesy of the excellent Mega Man Network.)

—–

* Oddly enough, Mega Man 6 features the characters Mega Man and Mr. X, which combined form the title Mega Man X.

** I’ve heard from a few folks that Wind Man does use the Wind Storm under specific circumstances. I’ve literally never seen it, and I’ve played through the game dozens of times. If anyone has proof of him using it, I’d like to see it. As it stands, I think this weapon has the dubious distinction of being the only one in the series that the Robot Master who wields it never bothers to touch.

*** I specify “console series” because weapon demonstrations actually debuted in Mega Man IV for the Game Boy, which came out a few months before Mega Man 6 both in Japan and North America. But I wanted to talk about weapon demonstrations in general, and I’m not covering the Game Boy games…yet.

I feel pretty similar about this title. The game feels like there was minimal creative thought put into it from a design standpoint, and so it feels like a boring slog to play through. Interestingly enough, the more I think about Mega Man 6, the more I feel as if it *could* have been the best classic series game to be made if it was handled better. Like, so many of the elements that the series had built up to are still there. The music is still phenomenal, and the graphics got noticeably better with each installment. The Rush Adapter idea is awesome! Without mentioning the story, the opening cutscene had utterly fantastic presentation: tense, catchy opening music with a quick slideshow of the events leading up to the game. Hell, I even like the story because of how obviously goofy and stupid it is.

Unfortunately though, like you said, it just ended up being one heck of an uninspired and forgettable game. It utterly baffles me how they screwed up the controls after perfecting the movement with 4 and 5. The game has a plethora of interesting enemies that are almost never used in interesting situations (which is compounded by the amount of enemies, like in Yamato Man’s stage, that are only ever used like once in the whole game). The structure of the levels is usually boring and rarely ever presents an interesting challenge. It only gets worse in the fortress levels where it just feels like they’re throwing miscellaneous enemies at you in stages characterized only by straight lines with a few bottomless pits thrown in.

Ultimately, MM6 ranks low with me too, but I could never help but shake the feeling that it could have been one of the all-time greats.

You know, I think that hits on something I didn’t realize. The frustration I have maybe isn’t just that it’s boring or uninspired…but that it didn’t have to be either of those things. There are a lot of great ingredients in 6, and I think I find something new to like every time I play it…but I also find more that I don’t like. The flaws don’t retreat.

This was one of my favorite MegaMan games, probably because I like platformers a bit slow and nonthreatening. Each NES MegaMan did seem to get a little easier than the one before… Generally I liked the music better than 5’s, which was almost as experimental as 8’s, though in some of 6’s tracks I got tired of one of the sound channels abandoning its harmony to do the same cutesy vamp over the long notes. KnightMan’s theme may have been the generic, meandering one of the bunch. And of course RockMan Complete Works 6 couldn’t have given us an arrangement of MegaMan 6’s revised introduction scene music…

I remember hearing about how the A button makes MegaMan stop and stand still when pressed in the middle of a slide, instead of jumping directly out of the slide the way he would in all other games. You have to double-tap A to jump after a shortened slide! Why couldn’t they have used Up to stand up from a slide like the later Game Boy games? I also remember being informed that the special weapons don’t have unique sound effects in this game! Why the sudden lack of attention to detail?

I think the developers just had too much fun designing effects for the Rush Adapters, in particular Rush Power. Yamato Spear’s gimmick may have been to break through shields, but it only works on a few enemies, while Power MegaMan can punch out all shields that I know of, and the punches knock many enemies back, send some sliding into others for mutual destruction, block off an enemy generator, and make a few bosses reverse course! Then with the charge-up function’s trick of trading range for power, there’s so much to play around with with Rush that they might as well have made Power the only weapon and designed a game around that. (Yeah, just make a little guy with rockets and power punches, call him “AstroBoy” or something.)

Actually where the design starts to bother me is in which boss hands out which bonus prize. FlameMan gives you Rush Power, which breaks through special walls, but he also gives you Flame Blast, which also breaks through another class of special walls. (It also functions like HeatMan’s throwing attack for MegaMan, which I always found amusing.) Wouldn’t it be more interesting if you had to decide which walls you wanted to be able to break through first? Then the four bosses that offer Beat parts (and the Energy Balancer) all require either a Jet flight or a Power punch to reach (and they all change their level palettes when you revisit them in some clumsy attempt to indicate this) and in fact all form a weakness chain that can follow Flame and Plant, so you’re basically forced into playing seven levels in a certain order if you want to use all the boss weaknesses while acquiring all the bonus upgrades. If only they’d spread the prizes out better and added more weaknesses, there could have been actual reasons to try a different level order!

I did make up my own boss weakness rationales for this game, but since like half of them are based on actual warriors from different parts of the world, I shouldn’t be sharing the ones that are like “[Nation] beat [Nation] once” for fear of starting a fight. And I can’t even guess what the advantage of Plant Barrier could be that it has to use double the energy of the seemingly-identical Skull Barrier. Smoother animation? Just seems like bad design to have to use its entire stock to defeat TomahawkMan, forcing you to take care never to slam it into him again during each mercy invincibility period. (But not as bad as being unable to finish MetalMan entirely with his weakness on Game Boy.)

Not sure if I said this before so let me make it clear now: I read every comment posted on this site, and I absolutely love the stuff you’ve posted regarding this series. Please keep it up. I always learn a little more than I knew when I wrote the piece, and in many cases you raise issues that I simply didn’t find a way to express. Thank you.

No problem! I didn’t know if anyone liked me going on criticizing my own favorites. I liked that MegaMan 6 at least tried to step up the presentation a little bit, and with a now-atypical ending for Dr. Wily… I think I like its many basic stage hazards, too. They don’t all have to be elaborate puzzles, you know! But (and this is probably bias from watching the TAS recently) I feel that too many of the enemies move too slowly to be a real threat anymore. PlantMan might be the one exception in having the robots frequently surprise the player. If that’s the one that provides Rush Jet, then I like the idea of taking on that extra challenge early for it!

I mean, they could have given it to WindMan and made it even more pointless to try an unusual level order. As it is, I find it much more natural to start with WindMan than to end with him, because FlameMan can be tricky enough to dodge to warrant extra help, but who has trouble dodging WindMan to the point of wanting to use the entire stock of Centaur Flash (carefully spaced out, remember)?

These write-ups are so fun to read. The Mega Man series has always fascinated me with its sheer volume; in the classic series alone you’ve got like 11 unique games, then Mega Man X has another 8. Mega Man Zero has 4 on one console. What prompted them to make so many of each series? Profits, inspiration? The games are pretty short so I suppose it wasn’t that time-consuming.

Have you thought about covering the Mega Man X games after this? No one seems to ever talk about those games beyond the first one and there’s no nostalgia culture surrounding it–you won’t walk into GameStop and see plushes of Zero or anything. But I personally think they’re a lot more fun and I’d love to see what you make of them, even if it’s just one post for the whole series.

Thanks for the kind words! Regarding the X series…stay tuned. I’ll have two pieces of good news about that soon. I’ll post something, most likely, around the time my Mega Man 8 retrospective goes live. Thanks for reading!