I’ll be honest, after watching The Lock In, I started to reconsider a few of my life choices. No, I didn’t stop masturbating. If anything, I’ve been masturbating far more frequently, just to spite it.

Specifically, I wondered if I made the right decision when I chose Christian horror as this year’s theme. Not that I was skeptical that I’d have anything to say — last week’s review made it quite clear that I would — but because…fuck. The Lock In was awful. Could I really make it through another two movies like that?

The answer, obviously, is no. No human being could. Which is why I’m glad to report that this week’s film, The Familiar, is far superior in every conceivable way. It’s still not a good movie, but it’s competent. Interesting. Periodically even intelligent. It does things I like. It features actors I like. It’s actually given me things to think about for weeks after watching it. I can’t say I recommend it, but I can say that I don’t feel like my time was wasted.

It was pretty okay!

I sat down to watch The Familiar with the expectation that I’d get through about 10 minutes, then get up and do something more fun, like eat a sack of broken glass. I’d return later for another dose and give up again. That’s how I had to watch The Lock In. (Here. I dare you to outlast me.)

It took me many sessions to make it through that hunk of crap, but The Familiar proved admirably watchable. Even through its worst moments, I never wanted to turn it off. I still could have been doing better things with my time, but I never felt that way, which is a genuine achievement.

I might not have liked the movie, but I liked watching it.

The Familiar actually does a decent job of preaching Christian value through popular media. What I mainly mean when I say this is that the film isn’t compromised by godliness. It has a strong spiritual bent and a number of clear spiritual messages, but the spirituality doesn’t get in the way of the film presenting realistically flawed characters.

The Lock In presented us with a group of kids (three…then four…then nevermind let’s just do the three) that we’re told deserve to be tormented by demons for some indeterminate amount of time. Yet none of their transgressions register to a secular audience. They don’t fight. They don’t steal. They don’t use profanity. They aren’t violent, rude, dishonest, or…anything bad, really. The worst they do is touch (literally just physically touch) a copy of Big ‘Uns. In fact, the kid with the video camera won’t even let the pornography drift into shot, so naturally virtuous is he. For crying out loud, their idea of a wild night is participating in a church lock-in.

They’re the most well-behaved little scamps in motion picture history, but director Rich Praytor thinks they deserve to have pitchforks driven into their heads all night for occupying the same space as photographic reproductions of women in various stages of undress. Forgive me if I don’t find that relatable.

But Sam, our equivalent flawed demon-bait here, is deeply relatable. He drinks. He curses. (A lot.) He’s slovenly. He’s a bit of a dick. He fucks. At one point, he seriously contemplates suicide.

The Lock In bent itself into a pretzel to ensure that it would be suitable for airing in a church basement. The Familiar doesn’t care. And the film is infinitely better for it.

What The Familiar understands is that you don’t communicate with people by speaking your own language. You communicate by speaking theirs. The Lock In was a movie by and for people who didn’t need it. The Familiar, at least relatively, understands the people who do.

Granted, Sam is the whitewashed, exaggerated sermon version of a sinner. But there’s humanity in his situation. In his struggle. In his fight against his inner demons that he needs to conquer before he can face his external one. And that’s good. Not unique, no…but serviceable. It functions. It makes this a real movie.

We meet Sam five years after the death of his wife, Katherine. He’s clearly distraught and unhappy. His life is an obvious wreck, and it’s a wreck of his own making. Later in the film we learn that he used to be a church leader of some kind, and that his father still is, but Sam has withdrawn. The fact that he never falls to his knees and blames God for taking his wife and ruining his world qualifies here as a kind of restraint, and it’s a welcome one. It’s obvious that Sam isn’t interested in dramatically blaming anyone…his response is the much more human retreat from the things that used to comfort him and bring him joy.

One day, without a clear explanation, Katherine’s little sister, Laura, shows up on his doorstep. The film is about the relationship they develop, Sam’s gradual emotional recovery, and a crazy pornography demon who chases them around.

You didn’t really think we were done with the pornography demons, did you?

Yes, I have to admit I laughed out loud when another Christian horror film (100% of the Christian horror films I’ve seen!) kicked off with kids looking at some porn they found. You know, come to think of it, are the kids really accountable for this? If they stole it from a convenience store or something, maybe…but if they’re just bumbling around somewhere and find it, as both sets of kids so far do, are they really to blame for anything?

The answer, obviously, is yes, and they should be tormented by supernatural gremlins for the rest of eternity.

To be honest, though, I’m not sure why this is here. It doesn’t set the stage for any of Sam’s later struggles — seeing this chance encounter blossom into a full-fledged pornography addiction could make it an effective cautionary tale — and it really only serves to introduce the presence of demons to the reality of this film.

Sam and his buddy Charlie — who will grow up to become the worst actor in The Familiar — find the pornography and are followed home by some sort of evil force. Many years later, the two of them must face and defeat that force. Why the force had to spring forth from a skin mag and not from something truly horrific — like a marijuana cigarette, or two men holding hands — is beyond me, but it’s all we get.

As an adult, Sam is some kind of gun dealer and/or repairman, and his friend Charlie is a fat cop. I don’t like using the word “fat” to describe a character, but we’d only have “cop” without it.

That’s the extent of his characterization, and roughly half of his scenes consist of him stepping aside to reveal Sam’s father. Sam’s father shows up about 50 times throughout the course of the film and each time it’s supposed to be a surprise. I kept expecting Sam to see Charlie at his door and roll his eyes, saying, “Hello, dad.”

The father’s role in this film is to repeatedly offer his help to Sam in fighting the pornography demon. Sam refuses his help in fighting the pornography demon 49 times. The 50th time, Sam accepts his help in fighting the pornography demon. Together, they fight the pornography demon.

So, yeah, The Familiar is pretty dumb. It’s the kind of movie that sounds like it has potential until you look past the synopsis. Nearly every decision is made poorly. It’s watchable, don’t get me wrong. And it has moments (and even stretches!) of genuine competence. But it’s not a good film, and it’s difficult to look at any aspect of it and not see room for improvement.

With one exception.

Laura Spencer plays Laura, and she’s…pretty great actually. To put it in spiritual terms, she redeems the film. She’s certainly what I’ll remember most about it, and she rises so far above the material she’s given it’s almost miraculous.

That’s not to say she’s good in this role. To be honest, she’s kind of not. But she exists on a plane of goodness entirely separate from the film. She may not be the right fit for the character, or what writer/director Miles Hanon calls on her to do, but she’s good on her own, independent of whatever other foolishness is going on.

There’s a disconnect between Laura and the rest of the film, which, as we’ll talk about it more, might seem to be an artful choice. But I honestly feel it’s a happy accident that came about simply because Laura Spencer is genuinely too good for it.

It didn’t take me long to pick her out as the brightest spot of the experience. She’s immediately sweet and warm. A welcome and uplifting presence, which works within the context of the film as a great counterpoint to the drab, dark life Sam is choosing to lead. But it goes further than that. It’s not a directorial choice; it’s a contrast entirely of casting.

Spencer is a natural. A delight. I found myself shocked that in the middle of this instantly-forgotten Christian horror film there was an actor who…I really liked. One I enjoyed spending time with. One I wanted to see more of. While I’ll never know for sure, I’d be willing to bet that Spencer herself is the reason I was able to watch this film in one sitting. She’s not in every scene, but there’s always the promise that she’ll be in the next.

Most of the actors in Christian cinema are ones that are either not talented enough to rise above the low standards of that particular audience, or ones that have fallen far enough professionally that they have no chance of rising again (such as Kirk Cameron or Kevin Sorbo). So my actual love for an actor here came as a surprise. And the more time I spent with her, the more time I refused to believe she belonged here. She should be doing better things. She’s capable of better things. She deserves better things.

And, well, there must be a God, because she indeed has had a pretty strong career post-The Familiar. I’d never seen her in anything before this, but it’s nice to know her star has been rising continuously. This film was one of three she appeared in during 2009, her first year acting professionally. After this she moved onto parts in far bigger projects, such as Criminal Minds, 2 Broke Girls, Bones, Sleepy Hollow, and, most significantly, a recurring role on The Big Bang Theory. In fact, that show has recently promoted her to series regular. That’s huge.

In short, the industry took notice of her, and it was for good reason. You can’t watch The Familiar and not enjoy the time you’ve spent with Laura Spencer. I’m glad she won’t be appearing in Christian horror any time in the future.

It’s amazing how just one excellent element of a film can elevate it, can cause you to open yourself up to it, can earn your attention enough for an otherwise undeserving project to hold it. I spent a good part of the movie not learning good Christian morals because I was trying to imagine what a perfect fit she’d be as Poison Ivy in a Batman film. Heck, it doesn’t even have to be a good Batman film. She’d make it worth watching on her own!

She’s also, it must be said, almost painfully cute.

This isn’t even a comment about her attractiveness…there’s just a natural, innate adorableness to her that simply can’t be overlooked. It’s part of who she is.

That’s a necessary comment, I think, because part of her character’s purpose is the temptation she poses to Sam. She’s supposed to be attractive. She’s supposed to be desirable. It’s fair to say Spencer is those things. But she’s also supposed to be sexy, as seen when Sam finds and is transfixed by a recording of a striptease she performed during an audition.

And…Spencer isn’t sexy. She comes across as too pure for that. As too likable. There’s nothing wrong with being sexy (unless you ask these films, natch) but there’s a difference between sexiness and cuteness, and I don’t mean any disrespect by saying Laura Spencer is in the latter camp.

I think we expect something specific of our sexy demons. A certain look. A certain behavior. A certain…something beneath the flesh, within, deeper, conniving, teasing, beating down our defenses…something irresistible.

Spencer is too cute to be a demon, because demons aren’t portrayed as cute. Angels are as cute. Demons are as sexy. I’m all for subverting expectations, but I don’t believe Hanon is doing that. I think he lucked into a solid actress, and then forced her into a role she doesn’t fit.

One doesn’t look at her and succumb to lustful urgency. One looks at her and wants to hug her. And adopt puppies with her. And beat up whatever guys broke her heart.

Spencer — and therefore Laura — triggers our urge to protect rather than our urge to protect against. She’s terribly cast for a demonic sexbeast, but perfect in her performance of a completely separate character the film doesn’t realize it has.

Because, yes, Laura becomes a demonic sexbeast. Or channels one. Or is manipulated by one. It’s not entirely clear, but I think that’s okay; ambiguity is probably a good thing when it comes to sexbeasts.

The main conflict of the film is that of the Madonna and the Whore. Laura, as you can easily enough guess, represents the latter, with her deceased sister easily filling the role of the former. This somehow manages to not be the most problematic thing about Laura’s treatment, but we’ll get to that.

Boiling females (characters or otherwise) down to those two roles is obviously a bit regressive, and looks even more quaint (and uncomfortable) with each passing year. If we were generous we could redefine these roles as Virtue and Vice, but Hanon’s intentions are clear.

Sam, for a long time, had the sobering influence of a Madonna in his life.

She was honest. She was loyal. She was godly in word and deed. This was Katherine, his wife. When she dies — when her influence is removed — Sam’s spiritual condition is tested by the intoxicating influence of a Whore.

This is emphasized by a genuinely artful moment in which Sam speaks with a hallucination (or spirit, or fantasy) of Katherine, during which the camera pans around to reveal Laura approaching from behind. She causes him to literally turn from his wife.

Sam should stand firm. Should rebuff Laura’s advances. Should bring her to penitence. That is his duty. Will he be strong, or will he lie with woman who is not his wife?

That’s not as much of a worry for a secular audience, and he ends up (relateably) sleeping with her. To a spiritual audience, this would represent a serious faltering. To a secular one, it just makes him human. It works either way, but it’s still a bit distressing that Laura is cast in a negative light for having — and wanting! — a sex life.

Why wouldn’t she? She’s young. She’s attractive. She has a good personality, behaves selflessly, and seems like an all-around decent human being. Would a sex drive automatically damn her? Would it be just if it did?

There are a number of strange aspects at play. It would be one thing if Katherine were still alive, as fornicating with her younger sister would pretty clearly be a jerky thing to do. But the fact that she’s dead — and has been for half a decade by the start of the film — makes it impossible to see the issue as black and white. It’s a very grey area from the outside, and it’s up to the participants only whether or not this is okay.

Are they consenting? Are they comfortable with the fact that they share a relationship to the deceased? Do they see this as being disrespectful to her or her memory?

I’m not here to judge. Personally, no, I don’t think I’d romantically pursue my dead wife’s sister. But I also can’t judge somebody else for the direction their life takes them. What’s more, much ado is made of the fact that Sam and Laura hadn’t seen each other for many years. (The last time was well before Katherine died, and Laura didn’t come to the funeral.) It’s not as though this retroactively makes previous interactions seem like flirtation; there was no connection. If there now is…is that inherently a bad thing?

The Familiar thinks so. I don’t know that I do. I think it’s a topic worthy of discussion, and exploration by an intelligent piece of art.

Intrafamily romances of varying degrees run through works of art from The Royal Tenenbaums to Arrested Development to The Hotel New Hampshire, and each of those works has something unique to say about the subject. In those situations I also wouldn’t behave the way the characters do, but, by the end, I don’t end up judging them, which is why it’s a little disappointing that The Familiar is only interested in judging them.

There’s something to say about this. There’s a valid question. He was happy with Katherine, but he isn’t the one who’s dead. Characters keep telling him to move on, and, yes, he does need to move on. If entering into a new romance is the way in which he chooses to do so, is that a bad thing? What if he and Laura are actually a better match? What if they end up loving each other more deeply? What if that relationship is better for them than his relationship with Katherine was for either of them?

It’s not enough to say, “No, it’s wrong,” and shut the door on discussion. Many, many kinds of sexual interactions are inherently wrong. Forming a relationship with an ex’s sibling is not.

Especially when the possibility is only raised for the purpose of dismissing one of those siblings as a Whore, which Hanon does here.

The contrast is clear and intentional, with the sisters each characterized by their opposition to each other. It’s also strongly suggested that the state of Sam’s soul is at play. He can follow the influence of his dead wife to Heaven — where, in the reality of this film, she certainly has gone — or the influence of her sister to Hell.

The end of the film makes clear that Laura is not beyond salvation, but her gravity certainly pulls Sam down rather than up. After all, the demon was released (or summoned, or awakened, or interested…it’s not clear) when the boys found the pornography. Laura not only attempts (successfully) to seduce Sam into actual, extramarital fornication, but she ultimately serves as a vessel for the forces of Hell themselves.

…man, we’re drifting really close to the despicable thing at the heart of this film that I really don’t want to talk about. Let’s yak for a bit about those forces instead. Or rather, that force, as Hell’s emissary (missionary?) here is Rallo.

Who’s Rallo? It’s not explained.

Why is he called Rallo? It’s not explained.

What is actually happening here? It’s not explained.

“Rallo” is such an uncommon and oddly specific name that I have to assume it means something, but unless The Familiar was hoping to do some cross-promotion with The Cleveland Show I’ve got nothing.*

Wherever the name comes from, Rallo is the demon Sam and Charlie face at the beginning and end of the film. Between those two confrontations, Rallo torments Laura, seemingly because something about her makes her a viable channel for him and his objectives. More on that to come…

Laura at one point is aware of some kind of presence in Sam’s home, and becomes very worried. It even attacks her at one point. She goes to Sam for help and he talks to her about spirits. Specifically, Sam tells her how to tell the difference between good and bad spirits: bad spirits hate the name Jesus.

Personally, I’d get Laura and myself the hell out of my house if we were being savaged by demons, but I guess his response is good, too.

Or, it would be, but his advice was pretty vague. Laura goes back to her room and feels the presence there again. She says Jesus’ name, and it seems to me like the demon gets upset. We don’t see the demon physically, but it’s clearly there, and it exhales in a kind of huff that blows her hair around. Seems pretty clearly like a negative response to me, but she takes it as confirmation that the demon is a good spirit, and that’s that.

Friends, if you’re staying in a house haunted by any spirit, go find a motel.

I’m tempted to see Sam’s advice as artfully useless. I want Hanon to be using this to illustrate Sam’s spiritual rustiness. Had he not been a drinking, cursing, fucking fool, he could have given Laura some much more actionable (or at least specific) advice. He explains that good and bad spirits can be told apart, but not in a way that helps her to reach the right conclusion. Especially since Laura has been physically assaulted by it, with the scars to prove it.

This should be a gimme. If Sam’s advice can’t help her see that the spirit that already attacked her is sort of bad, he’s genuinely useless.

I’m not really sure if we’re meant to see it that way, though. We can read it that way, but it doesn’t play that way in the film. Usually when attention is drawn to Sam’s shortcomings, it’s drawn clearly and without potential for misunderstanding. This is hugely important in a didactic film; if you leave any room whatsoever for your audience to admire the wrong traits, some of them will. Therefore you can’t leave these things to interpretation.

As a related example, at one point in the film, after Rallo is riled up and on the offensive, Sam and Laura both panic. Rightly so. Sam sees an opportunity to flee the house, but doing so would leave Laura behind, at Rallo’s mercy.

And he indeed leaves her behind.

The film doesn’t treat this as a positive thing. I’d certainly agree that it isn’t. We could debate the ethics on either side (is guaranteed survival for one party better than a reduced possibility of survival for both parties?) but I actually like the way the film plays this moment. It’s a human response, and it’s a flawed human response.

It’s a plot point and characterization at once. And, of course, it both sets the stage for and makes it more rewarding when Sam actively stands up to Rallo to save Laura at the end. The plot has progressed, but so has Sam. He’s grown. It works.

But — and this is my main point here — all of that happens very clearly. We don’t see Sam leave Laura to Rallo’s attack and believe he made the right choice. The film won’t let us see it that way. Ditto the amount of time he spends watching Laura’s ostensibly sexy audition tape; we know he’s wrong to keep watching it, and every second his decision grows wronger. There’s no opportunity to read it in any other way.

So when he gives lousy advice to Laura about telling demons apart, I’m not convinced it’s deliberate evidence of his flawed spiritual state. I think it’s just clumsy writing. Laura’s told what to do, she does it, and she comes to the wrong conclusion.

If this were a better film, perhaps Laura would have had her own wrong ideas about how to tell spirits apart. Perhaps they could have been based on…let’s say…her personal spiritual leanings, which aren’t in line with Sam’s correct ones.

Hey, actually, now that I mention it…

Okay. Deep breath. Here we go.

Laura is a good person. Possibly even a great person. She’s human, so she makes mistakes and acts in her best interests at times whether or not it’s the “right” thing to do. But as a member of the viewing audience and not a member of the production team, I’m confident in saying that Laura’s a good human being. I’d get along with her. I think most people would. She deserves good things and I’d look forward to seeing what she does with her life as she grows and matures.

Hanon clearly disagrees. And he disagrees because he’s viewing her through a different lens than we would (and should) in reality.

This is part of the inherent problem with religious media. When you wish to promote particular values, characters who don’t share those values are automatically wrong. And while you probably realize this, I’ll say it anyway: I’m not referring to large, ethical, relatively universal values. I’m not referring to “don’t kill.” I’m not referring to “help the needy.” I’m not referring to “don’t torture animals.”

I’m referring to…well, in this case, Christianity.

And while Christianity at its core can be said to be a religion of love, ethics, and honesty, many rules (formal and informal) have built up around it, so that being a good person is no longer enough. You also have to do a, b, and c, as well as avoid x, y, and z. There are expected behaviors, habits, and mindsets that — from a social standpoint at the very least — inform what it means to be a good Christian.

Those change — in nature, number, and degree — between denominations, but there’s always** more to it than belief. There’s a world of functional difference between the Silent Worship of Quakers and the testimony-based, door-knocking approach of Mormons, even if the roots of their beliefs are quite similar.

I wasn’t able to identify the specific denomination that The Familiar endorses, but it certainly endorses something. It’s not enough to be a good person or even to be Christ-like; you need to do and believe very specific things, lest you become a conduit for evil.

Case in point: poor Laura.

Laura gets dragged through the mud, both by the film and by the characters within the film. And at no point does she deserve it. While we can point at decisions she’s made and disagree with them, we can (and are encouraged to) do that with Sam, as well. It’s not a matter of someone getting everything right and someone else getting everything wrong; it’s a matter of only one character getting things right in the right way. (She even says, in the spirit of tolerance, “To each his own,” regarding the fact that Charlie and Sam have different values than she does. They look at her as though she slapped them.)

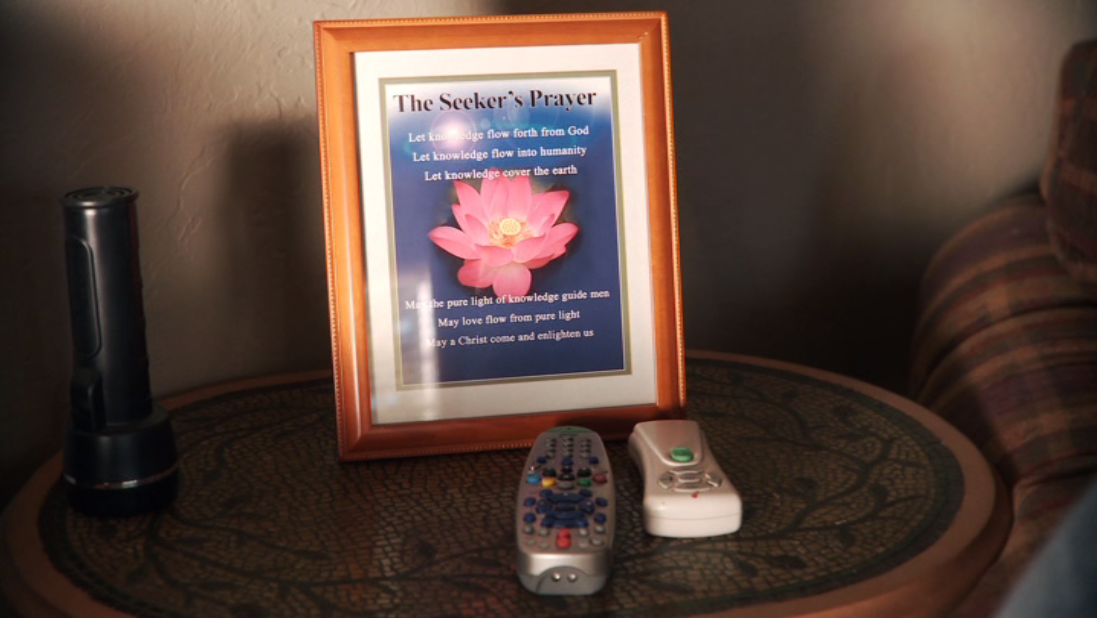

Laura’s crime is that she gets things right in the wrong way. She’s not whatever specific kind of Christian The Familiar thinks she should be. She’s a Light Seeker.

I’ve found some people online who call themselves by the same name, but I get the sense Hanon invented the concept for his film as a kind of catchall. (For what? We’ll get to that.) I think any actual relation to real-life Light Seekers is coincidental. Hanon didn’t make The Familiar to tear real-world Light Seekers down. He made The Familiar to caution against following anything other than The One True Path.

And so when Laura shows up at Sam’s door, she’s not a negative influence in any kind of secular sense; she’s only a negative influence through a very specific (and very narrow) spiritual lens. She believes something other than what Sam believes, which means she has the potential to pull him further away from the truth.

That’s it.

That’s what makes her a vessel for evil.

Here are just some of her nefarious deeds. She cleans up Sam’s house for him, so that he is no longer living in the Christian horror film equivalent of squalor. She performs much needed maintenance around his house, such as clearing gutters and taking care of the yard. She speaks to him about his problems and fears, encouraging him to work to overcome the emotional hurdles that have destroyed his life.

Oh, and she literally prevents him from committing suicide. It’s her ring of the doorbell that keeps him from pulling the trigger.

Laura’s first action in the film is to save the life of our protagonist, and she’s still made out to be a negative influence.

The Familiar cares a lot about the Bible, but doesn’t seem all that interested in the “by their fruits, ye shall know them” bits. Despite that passage in Matthew making it clear that “good fruit” cannot come from a corrupt tree, Laura provides only good fruit, and yet is also explicitly made out to be a corrupt tree. That’s bad theology and bad characterization at the same time. (The Bible literally laid out the rules for your characters!)

In fact, I’d argue that Laura’s production of good fruits happens far more frequently than Sam’s. Early in the film they have a discussion about their respective faiths. Oh, actually, wait, my mistake. Early in the film, Sam chews her out for believing something other than what he believes.

The confrontation occurs over a framed Light Seeker prayer Laura displays. It’s so similar in content to the various framed prayers I’ve seen in my life that I can’t imagine Sam having an issue with it. But he does.

When he brings it up, Laura demonstrates an openness to the faiths of others that Sam makes it clear he doesn’t share. Laura is willing to listen, to learn, and to accept. Sam is willing to do nothing but shut down those who don’t already believe in him. She’s open to Sam’s personal views of Christianity, whereas Sam is not open to hers.

Specifically, when she discusses her beliefs, sharing with him something that’s deeply personal to her, he replies, “Are you an idiot or something?”

This clearly hurts her. She stands up and leaves the room so that he won’t see her cry.

Which is the good fruit? Who is the better person?

It ultimately comes down not to the roots of their beliefs (neither of which, tellingly, are ever mentioned) but to the labels, to the rituals, to the symbology of each. We’re both right, but I’m right in the right way.

And, of course, this mindset manifests itself in our world not just theologically, but politically.

The democratic divide is significant. It’s why certain voters never accepted Obama as a Christian, no matter what they heard through his words or saw through his deeds, while those same voters do accept Trump as one…in spite of his words and deeds. In spite of their quality of the fruits they bring forth. In spite of their respective tendencies toward unifying and dividing.

I use these two as examples because they’re recent, of course; I’m not trying to make a grand point about Obama or about Trump specifically. But it is clear that in a general sense, much of the “true Christian” mindset extends to the political sphere. It’s not enough to disagree with somebody…it’s our obligation to vote against them.

As such, The Familiar is filled with conservative dogwhistles. We don’t see Sam lamenting the then-recent defeat of John McCain, but we do see his quaint, homey, conservative view of the world threatened by a woman who will literally serve as a demon’s surrogate.

In brief, she’s more liberal than he is.

She expresses feelings of acceptance. Of tolerance. Of peace. She’s sexually liberated. She’s made mistakes but doesn’t carry around her guilt. She seeks and discusses opposing viewpoints. Hell, at some point she even says she doesn’t see why people should own guns! That’s one step away from forcibly taking guns away from all true Americans!***

These aren’t bad things. These are the things that make her likable. And yet they are also the things that, in The Familiar, ultimately make her a monster who must be stopped.

The political aspect doesn’t take much digging to find. (In fact, it doesn’t take any; it’s right there on the surface and lacks only an explicit label.) Much like Katherine and Laura, Sam and Laura are defined by their opposition.

Katherine’s status as Madonna reinforces Laura’s as Whore, and vice versa. And Laura’s unwelcome intrusion into Sam’s rural, small-town, literally backwoods life serves as its own dichotomy. (She’s from, as though this says it all, “the city.”) They have opposing values, and in order for the film to be didactic at all, one set of those values has to conclusively be proven wrong.

That’s a dangerous and destructive mindset. Wherever you fall on the political spectrum, it’s foolish to believe that we can’t accomplish more when unified than we can while divided. Hanon has the right to say whatever he likes — it’s his film, and, frankly, it’s not a half-bad one — but I do think The Familiar would work better, and be more focused, if it were entirely about a struggle for Sam’s spiritual state, and not about one worldview functioning as the path to Heaven with the other being a direct portal to Hell.

Toward the end of the film, Rallo possesses Laura and tells Sam that Laura only came to him in the first place because she was pregnant, and she wanted him to help her raise the child.

Of course, since this is a demon speaking, we don’t know if there’s any truth to it. (Wisely, Hanon doesn’t confirm it either way.) But it’s framed, obviously, as a terrible thing for Laura to do, and evidence of her status as Whore.

In reality, though, I’m not sure that it is. It’s not clear what specifically made Laura a valid receptacle for Rallo. It could be her sexuality. It could be her liberal bent. It could be her openness to hearing others out. (The line, one might suggest, should be drawn before hearing out actual demons from Hell.)

But the climactic placement of Rallo’s explanation in the film suggests that Laura’s intentions when running to Sam were evil, giving the demon something to latch onto. It even knocks Rallo for a loop when Sam says, “Okay, sure. I’ll raise the kid. Now what?”

Rallo has no answer. He really thought that was his ace in the hole.

We don’t know if Laura was really pregnant. But even if she was…and even if she wanted Sam to help raise the child…what’s the problem?

Granted, she didn’t tell him about the child, but maybe she was waiting. Maybe she wanted to get a sense of what Sam was like now — and what his life was like now — before foisting a child on him. Maybe she did come with the intention of swindling him into caring for the kid, but thought better of it when she realized she had actual feelings for him, and might be able to create a real family together. Or, hey, maybe the fact that she was being chased around by Satan Jr. made some other things slip her mind.

The fact is that this grand reveal is meant — based upon its structural context — to cement Laura as the bad person in need of redemption. This again in opposition to Sam, the good person who is standing up to a demon as proof that he’s been redeemed.

But it doesn’t make me like Laura any less. Much like the casting of Spencer herself, the character isn’t a believable demon. She’s too good. She’s too real. Her flaws don’t register as flaws.

As much as the movie wants me to judge her, it’s hard to ignore the fact that nearly everybody I know in life has done far worse than she has, often with worse motives…and yet they’re still people. I’m okay with them. I like them, and I want to see them grow and mature and succeed.

I can’t hate Laura. I can’t hate Sam. All I see are two flawed people that have a lot in common at their cores, yet who we’re supposed to view as diametric opposites. I don’t think that either of them is right, and I don’t think that either of them is wrong. I think they both have a lot to learn, but I honestly feel as though Laura is closer to learning it. If that makes me a conduit for evil, so be it. If I show up pregnant on your doorstep, feel free to throw me out.

I just can’t help but wonder if The Familiar would have been a better movie if it were about two people learning from each other, rather than a movie about one learning from the other…especially when the other is kind of a fuckup.

It didn’t have to be this way. There’s a lot The Familiar does right. But it also strikes a sour, divisive note. It reinforces the concept of a definitive right way and a definitive wrong way to live one’s life, but it doesn’t provide a compelling argument for it. It’s right because it’s right, and that’s that.

There’s a decent personal story buried here, and sometimes it’s not even buried too deeply. The Familiar is about a man facing his demons who eventually ends up facing a demon. That can work. It falters when it casts the first stone at Laura, who is far more of a redemptive force than the movie actually realizes.

I didn’t hate The Familiar. I can’t say I recommend it, either. But it’s stuck with me. It’s given me things to think about.

And, one day, when Laura Spencer is the star she deserves to be, it will serve as one Hell of a fascinating footnote.

—–

* If there’s not a church-oriented PR firm called Cross Promotion there can be no God.

** Of course, I’m speaking of organized Christianity. Any human being has a right to follow whatever teachings they like in their own way. The moment you structure it, though, the maintenance of that very structure becomes an additional concern.

*** Charlie warns Sam as follows: “Anybody that doesn’t like guns…gotta be something wrong with them.” Sure enough, she opens the portal to Hell. This is why we don’t tolerate dissent, people!

Another outstanding write-up, and this one actually inspires me to see the film. (But that would require effort, so I won’t.)

–

Again the curious issue of target audience is raised for me. I can see that The Lock-In, although void of cinematic quality, might appeal to a young, non-critical Christian audience. At least it deals with your peers and addresses things that are genuinely scary. And at the same time, for the reasons you give here, The Familiar, although far more interestingly constructed and thought-provoking, would probably fall flat to its intended audience. “Gee, I dunno. I realize that gal is off base, but she really doesn’t seem THAT bad…”

–

Lesson to aspiring Christian horror film producers: Run your script by Phil first. If he likes it, rewrite. If he finds it irredeemable, proceed as scheduled.

–

I like Rallo, I really do. It was revealed to me in a dream about 30 years ago that the demon who inhabits me is named DEON. That’s right, like Deon and the Belmonts, the dude who sang “Abraham, Martin, and John.” So I don’t find Rallo that odd a name.

I came *this close* to complaining that this movie has much the same flaw that “The Lock In” does–that the dangers involved aren’t the real ones that follow from sin. Not only does “(doing whatever with) porn unleashes actual named demons” not register with most mainstream Christians (much less secular viewers), it borders close to lying on the part of the Christian filmmaker. Go as far as “The Lock In” does, and it comes across like one of the “and that’s why you don’t…” scenes from Arrested Development. Go too far towards realism and you cut off potential horror movie tropes like being possessed by demons. It’s a tension that–now that I’ve realized it–I want to see more Christian horror films to see how it’s handled.

.

I was going to say that “The Familiar” does the same thing… but I think that the climax of this movie is what some Christians believe could happen outside of God’s protection. Jesus talked to–and cast out–demons possessing people. (There’s also a long history and academic discussion of repressed female sexuality and “demonic possession” that I am in no way qualified to summarize, but which I’m sure would have a lot to say about this movie.) So for many viewers, this may very well be a realistic horror movie.

.

It’s really hard to keep my own criticisms of Christianity reined in making comments for these, so let’s see if I can keep it about the films themselves. Your review butts up on the periphery of the faith vs works discussion. You’re absolutely right to ask why good behavior doesn’t amount to a (calvary) hill of beans if the person doesn’t believe the exact right thing. I’d argue that it’s the content of the belief itself that lends it that importance according to Christianity. But salvation by faith is a tricky, precise argument to make, and it’s apparent this film didn’t argue it successfully for at least one viewer.

.

Now that I’m thinking about it, “The Familiar” is like “The Lock In” in terms of their focus. Both are discussing the dangers of sin (not to mention sharing a deep unawareness of gender roles in Christianity), which is really just one side of the equation. In Catholic teaching, there are sins of commission and sins of omission. Why not a horror film about zombie-like Christians who focus only on not sinning but don’t take time to help others? Call it “Faith Without Works is Undead”

And so it came to pass that in this way Casey became the first of all men who burden on this earth to say, “I want to see more Christian horror films.”

–

If I may pitch in re: faith vs. works, it is true that the specificities of all Christian denominations are different. Some may even have different opinions concerning the exact requirements for salvation… e.g., is baptism necessary?

Those that adhere to salvation through faith, however, all agree on one thing: Jesus paid the price so that you don’t have to. So, I think the film’s intention isn’t to show that Laura Spencer’s faith lacks the proper components. I think it’s rather that her “it’s all good” mindset betrays a LACK of Christian faith–i.e., she turns a blind eye to the Christian truth that we deserve eternal torment (or separation from God, depending on your interpretation, although the Bible clearly says the former), and that Jesus is the only way out. The target audience would recognize Laura’s beliefs as too much of the world and not enough from the New Testament.

Interesting thoughts here, from both Casey and Jeff, and they led me to wonder about two things I didn’t discuss above.

–

1) “Faith without works is dead,” sure, that’s an easy one. We can all understand that. Believe the right stuff but don’t actually follow through with those beliefs and you don’t get through the pearly gates. Fine, and a Christian film (horror or otherwise) shouldn’t have to work too hard to demonstrate this.

–

But Laura’s character strongly suggests that “works without faith is also dead, and maybe deader.” And I think a Christian film would have to work pretty hard to convey that successfully. I’m not even sure it can. “You won’t get to Heaven” is obviously an easy caution to offer the audience, but if they don’t believe in Heaven, it doesn’t mean anything to them, and devaluing “works” (being a good, selfless, supportive, helpful, caring human being, such as Laura is) comes across as insulting.

–

If two hypothetical characters — a Christian and an atheist — perform exactly the same works, does the atheist’s works inherently mean less? Why should they? Certainly he’s not performing them with any expectation of reward in the afterlife. A Christian film has every right to point out that he won’t get to Heaven, but that’s his business. What should it matter to an outsider? And, frankly, if he dedicates what he believes is the only life he will ever get to helping others, that’s pretty heroic to me. He gets a few decades to do as he pleases, and he chooses to make the world a better place, expecting that he’ll never see or reap the results of his work. It’s strange — but by no means unexpected — that a Christian film would position this as a tragedy.

–

Oh well. Viva divisiveness.

–

2) Casey’s idea of zombie-like Christians avoiding vice but not practicing virtue, or following the letter of the law but not the spirit, is obviously a superior one. But after this series, I’m reasonably convinced that in Christian horror, the call is never coming from inside the house.

Interestingly, the Bible has something to say about marrying the sibling of your deceased mate.

Deuteronomy 25:5-6

“If brothers dwell together, and one of them dies and has no son, the wife of the dead man shall not be married outside the family to a stranger. Her husband’s brother shall go in to her and take her as his wife and perform the duty of a husband’s brother to her. And the first son whom she bears shall succeed to the name of his dead brother, that his name may not be blotted out of Israel.

There’s also a name for this – Levirate marriage.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Levirate_marriage

That IS interesting. I can’t imagine Hanon had this in mind when he wrote the film, but I honestly didn’t know the Bible offered any guidance in this regard. Thanks!

Agreed, it’s an interesting point! The infamous Onan, BTW, was victim of this requirement. When he had second thoughts about impregnating the old sis-in-law, ZAP. The end. I also agree that Hanon didn’t bear this in mind, but in a logical world he would have.