Well, sort of!

My time with Star Trek has come to an end for now. I’ve made it to the end of The Original Series, but I do intend to watch the films at some point in the near-ish future. After that? I’ll almost certainly get around to The Next Generation, Deep Space Nine, Voyager, and maybe some other things as well. I’m open to suggestions, but those are all stories for another time.

Right now, I’m taking a look back at season three of The Original Series. I was interested in this season for extremely selfish and thoroughly disrespectful reasons. Or, reason: “Spock’s Brain.”

For decades I had been hearing about how terrible this episode was. It wasn’t just the worst episode of The Original Series; it was among the worst episodes of television, full stop. How could I not want to watch it? That, as Van once put it, was honey to the bee.

We can learn a lot from the way things fall apart. Sometimes it’s our only real chance to get a peek inside something we love. When a piece of media works — truly, thoroughly works — it’s like watching a magician. We see only what we’re supposed to see; everything else is concealed or (to be more accurate) distracted from. We get caught up in the illusion, with the narrative or characterization or dialogue or filmmaking keeping us so engaged that everything else remains unseen. And, therefore, might as well not exist.

We can learn a lot from the way things fall apart. Sometimes it’s our only real chance to get a peek inside something we love. When a piece of media works — truly, thoroughly works — it’s like watching a magician. We see only what we’re supposed to see; everything else is concealed or (to be more accurate) distracted from. We get caught up in the illusion, with the narrative or characterization or dialogue or filmmaking keeping us so engaged that everything else remains unseen. And, therefore, might as well not exist.

When a piece of media doesn’t work, when you see its guts spilling out all over the place, though, it’s brilliantly fascinating.

Something that is supposed to make us weep is making us laugh. Something that is supposed to move us is amusing us. Something that is supposed to form a coherent whole instead unspools as we watch it.

That’s thrilling to me. I love it. As a writer, I am able to learn from it. As a member of the audience, I am able to revel in it. I don’t hope for movies or television shows to be lousy. Ideally, I’d love everything I watch to be perfect forever. But if something is lousy, I want to see it. I want to know exactly how it went wrong. I want it to educate and entertain me in its failure, because it’s ironically difficult to learn from the things that get everything right.

And so I wanted to watch “Spock’s Brain.” I could have done so easily, at any point. Star Trek isn’t difficult to find legally, and I’m sure if I were willing to do illegal things it would be even easier. All I needed to do, basically, was set aside an hour of my time.

And so I wanted to watch “Spock’s Brain.” I could have done so easily, at any point. Star Trek isn’t difficult to find legally, and I’m sure if I were willing to do illegal things it would be even easier. All I needed to do, basically, was set aside an hour of my time.

But I didn’t want to do that. Not on its own. I had a feeling that watching “Spock’s Brain” in isolation wouldn’t give me the full scope of just how awful it was. And that’s mainly because I knew Star Trek was beloved for a reason.

Television shows, by and large, are slick productions. There are great episodes and terrible episodes, of course, but terrible episodes don’t usually feature boom mics dipping into frame, sets falling apart, actors forgetting their lines, or other such superficial indications of awfulness as we often get in bad films.

The reason for this is simple: Television shows offer regular employment. The production staff has often been with the show for long periods, and has been working in the industry for even longer. No matter what a particular episode consists of — from brilliance on down to nonsense — they know how to shoot it, how to edit it, how to package it into a tidy little product for the audience to consume.

The writing may stink, the story may be idiotic, and narrative logic may be absent, but in terms of production, these people know what they are doing. A crappy filmmaker will assemble an incompetent crew and give us something that fails by every metric, but in television this simply doesn’t happen. Individual episodes don’t have individual crews. Specific members of that crew come and go, but never all at once and for the duration of a single episode. Production competence is the background hum.

The writing may stink, the story may be idiotic, and narrative logic may be absent, but in terms of production, these people know what they are doing. A crappy filmmaker will assemble an incompetent crew and give us something that fails by every metric, but in television this simply doesn’t happen. Individual episodes don’t have individual crews. Specific members of that crew come and go, but never all at once and for the duration of a single episode. Production competence is the background hum.

On top of that, Star Trek in itself was a well-made show. People loved it because suspending disbelief was easy. Walls can wobble and makeup can look ridiculous, but it’s not difficult to look past those things and see, at its very sturdy core, that the show was projecting a universe we could understand. I can say that with confidence now, as I just watched most of it for the first time 50 years later, and I had no personal or nostalgic attachment to it at all. If I thought the show worked, it’s because I really did think — as an adult with more or less fully developed critical faculties — the show worked.

Which means “Spock’s Brain” must have been bad for other reasons. Reasons a non-fan probably wouldn’t understand. And so I didn’t think it was fair of me to watch “Spock’s Brain” before having a baseline understanding of what Star Trek offered on a weekly basis. That would only be fair to the show, and it would help me to better appreciate the precise way in which the wheels of “Spock’s Brain” came so fascinatingly off.

Now that I’ve seen it, I can honestly say that…

Okay, yes, it’s bad. It is a bad episode of a show that had been, in large part, quite good.

Okay, yes, it’s bad. It is a bad episode of a show that had been, in large part, quite good.

But it’s not that bad.

We’ll get to this in greater detail but, for now, let me say that I’d heard almost nothing but negative things about season three. In fact, as uniformly as people claimed season two was by far the best, they claimed that season three was by far the worst. As you know from my previous Star Trek post, I didn’t think season two was all that far above season one. Overall, yeah, it was better, but not by enough to matter.

And so I figured that season three might not be as bad as its reputation suggested. Maybe it would indeed be the worst of the three, but — again — not by enough to matter. Perhaps it came in third place only because something had to come in third place. Maybe the disappointment of “Spock’s Brain” — which was a frankly idiotic choice for season premiere — tarnished opinions in a way it wouldn’t have if it had come much later, after a string of better episodes.

I had convinced myself that this must have been the case. Then I actually started watching season three, and became immediately more confident in my assumption.

We’ll come back to “Spock’s Brain,” which indeed sucks on toast, but after that episode, we were in really good hands again.

We’ll come back to “Spock’s Brain,” which indeed sucks on toast, but after that episode, we were in really good hands again.

“The Enterprise Incident” was a fun and engaging heist story, with our heroes infiltrating a Romulan vessel and stealing some dangerous technology. It had an excellent guest star in the form of the Romulan commander, who is toyed with and manipulated emotionally by Spock. She gets her feelings hurt, understandably, and Spock ends up feeling no better, surprisingly. It was a nice, compact little adventure with great twists and a bit of sad characterization as well. I wouldn’t rank it among my favorite Star Trek episodes, but certainly it belongs on the list of good ones.

And the good episodes kept coming.

“The Paradise Syndrome” saw Captain Kirk dreaming openly about settling down one day on a peaceful planet, only for an unfortunate accident to wipe his memory and leave him doing exactly that. “Is There in Truth No Beauty?” was a smart episode about perception and preconception, with another fantastic guest character and some impressive meditations on the nature of love. “Spectre of the Gun” was an amusing, surreal episode about the Enterprise crew being forced to participate in a reenactment of the Showdown at the O.K. Corral.

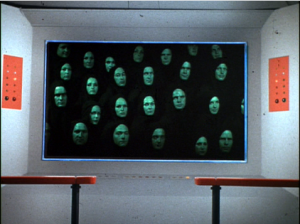

Have I skipped over anything? Oh, right, “And the Children Shall Lead,” which…wasn’t great. It had a decently haunting premise (the crew arrives at a colony in which all of the adults are dead, and they learn quickly that they were killed by their own children) and an excellent scene with Nurse Chapel interacting with the kids, but it falls apart when it’s revealed that it’s all the work of a glowing evil fat guy.

Have I skipped over anything? Oh, right, “And the Children Shall Lead,” which…wasn’t great. It had a decently haunting premise (the crew arrives at a colony in which all of the adults are dead, and they learn quickly that they were killed by their own children) and an excellent scene with Nurse Chapel interacting with the kids, but it falls apart when it’s revealed that it’s all the work of a glowing evil fat guy.

Just about any other direction this episode could have taken would have been better, but that’s okay. This is just one stumble along a very strong stretch.

Then we had “Day of the Dove,” which is just fantastic. At its heart it’s about a creature that feeds on negative emotions, but the actual story is smarter and more interesting than that. It’s really about the conflict between the Enterprise crew and the Klingons.

Then we had “Day of the Dove,” which is just fantastic. At its heart it’s about a creature that feeds on negative emotions, but the actual story is smarter and more interesting than that. It’s really about the conflict between the Enterprise crew and the Klingons.

While the creature indeed manipulates them into mutual aggression, it’s more of a gentle nudge than an outright push. The crew and the Klingons already think so poorly of each other and are so suspicious of each other that they immediately assume the worst. They punish each other and take action against each other before they know if there’s a reason to do so, because they assume that of course there is a reason to do so.

It’s a graceful evolution of the idea introduced in season one’s excellent “Errand of Mercy,” which established that Kirk and the Klingon commander weren’t all that different. One may ultimately want peace a bit more than the other, but the more indistinguishable their methods turn out to be, the less convincing the “peace” argument becomes. It’s a great episode with some excellent insight.

Then there’s “For the World is Hollow and I Have Touched the Sky,” which sees my precious Dr. McCoy finding out that he doesn’t have long to live. On its own that could be a great story, but it’s layered atop another story, about a race that doesn’t realize it’s not on a planet; it’s on a multi-generational spaceship that is on a collision course and will be destroyed if it isn’t diverted.

Then there’s “For the World is Hollow and I Have Touched the Sky,” which sees my precious Dr. McCoy finding out that he doesn’t have long to live. On its own that could be a great story, but it’s layered atop another story, about a race that doesn’t realize it’s not on a planet; it’s on a multi-generational spaceship that is on a collision course and will be destroyed if it isn’t diverted.

Two visions of a looming end, explored differently but in ways that overlap thematically as well as narratively. McCoy behaves in ways he would not behave in other episodes, but here it makes sense. We aren’t seeing the Bones we know and love; we’re seeing a desperate Bones trying to come to grips with the fact that he has no future, aside from whatever he chooses to do right here and now. It’s a flawed but wonderful episode.

I assume I’ve made my point by now. The first stretch of season three had a pair of stinkers, but it was otherwise composed of episodes that could stand shoulder to shoulder with the best stuff the show had done prior.

I was vindicated. Season three wasn’t bad; season three got off on an unforgivable foot with “Spock’s Brain” and fans found it difficult to take the season seriously after that. It squandered more good will, fairly or unfairly, than the rest of the season was able to win back. What a relief.

I was vindicated. Season three wasn’t bad; season three got off on an unforgivable foot with “Spock’s Brain” and fans found it difficult to take the season seriously after that. It squandered more good will, fairly or unfairly, than the rest of the season was able to win back. What a relief.

Then, friends…my lovely, wonderful friends…the season really did take a nosedive.

Roughly the first half of season three compares favorably enough to what came before, but the second half of season three is a genuine shambles. Where I could see moments of weakness in the first stretch of episodes, I was celebrating any moments of decency in the final stretch.

My first indication that something was wrong came with the abysmal “Plato’s Stepchildren,” which seems to trip over itself trying to become as stupid as possible as quickly as possible. At one point I was watching a little person ride William Shatner like a pony while the latter neighed with delight. (That little person had by far the most dignified role in the entire mess.)

My first indication that something was wrong came with the abysmal “Plato’s Stepchildren,” which seems to trip over itself trying to become as stupid as possible as quickly as possible. At one point I was watching a little person ride William Shatner like a pony while the latter neighed with delight. (That little person had by far the most dignified role in the entire mess.)

A couple of episodes later we got the miserable “The Empath,” which saw the crew being slowly tortured within an inch of their lives. What fun we have on this space adventure! There was “That Which Survives,” which was about a computer or something. There was “The Savage Curtain,” during which Kirk meets Abraham Lincoln and a rock monster. The season even ended on an extraordinarily low note with “Turnabout Intruder,” in which Kirk is possessed by — gasp — a woman!

When people tease Star Trek for its writing, for its acting, for its corniness, these must be the episodes they are referring to. Watching the first two seasons — and much of season three, at first — the criticism struck me as overblown. As though people were remembering and responding to an exaggerated echo of Star Trek rather than what Star Trek actually was. As though they were judging the show based on jokes about it and parodies of it, rather than anything it actually did or failed to do on its own.

But shit lord did season three really hit rock bottom.

But shit lord did season three really hit rock bottom.

Which means I should have been in heaven, right? If I love watching the wheels come off, a previously great show now falling apart on a weekly schedule should be one hell of a lucky break for me!

The problem, though, is that the episodes I just listed are not interesting failures. They’re boring. They’re repetitive. They’re superficial.

I’m not watching a show that stretched too far and couldn’t say what it wanted to say; I’m watching a show floundering for anything to say. I’m seeing finally, for the first time, some actors showing up and putting on costumes and saying the lines they need to say before they can cash their paychecks. Star Trek, surprisingly quickly, became a joke, and not an especially good one.

Do you want to know what was an interesting failure, though? “Spock’s Brain.”

Do you want to know what was an interesting failure, though? “Spock’s Brain.”

I can’t imagine watching all of Star Trek or even all of season three and concluding that “Spock’s Brain” is as bad as it gets, because “Spock’s Brain” is entertaining. It’s so dumb that it becomes riveting.

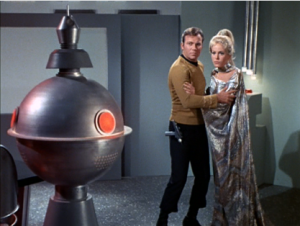

It’s about a colony that needs a brain to operate its supercomputer, and so they steal Spock’s Brain — right out of Spock’s Head — without anyone noticing. When the crew shows up on the planet to track it down, they bring a literally mindless remote-controlled Leonard Nimoy with them. When they find Spock’s Brain, Dr. McCoy has difficulty putting it back into Spock’s Skull, until Spock’s Mouth talks him through the process.

And these are just the broadest strokes; “Spock’s Brain” is masterfully imbecilic.

The idea of a society needing an organic brain to keep itself operational is fine. There are better premises, certainly, but you could kick off a good story with that one. What we get, though, is almost miraculously terrible, and the episode keeps finding new ways to get stupider.

The idea of a society needing an organic brain to keep itself operational is fine. There are better premises, certainly, but you could kick off a good story with that one. What we get, though, is almost miraculously terrible, and the episode keeps finding new ways to get stupider.

In the other examples I mentioned, the episodes find only one way to get stupid, and it’s typically the easiest, laziest way. Nothing is interesting about a plot that doesn’t go anywhere.

“Spock’s Brain,” by contrast, goes everywhere.

In many cases, even season three’s disappointing episodes do have something to recommend them. It’s difficult to entirely squash the charm, especially when the charm comes from as many different directions as it does in Star Trek.

In many cases, even season three’s disappointing episodes do have something to recommend them. It’s difficult to entirely squash the charm, especially when the charm comes from as many different directions as it does in Star Trek.

“The Tholian Web” didn’t do much for me, but the special effect of the titular web being weaved was fucking incredible, particularly when taking into account the era and the budget of a weekly TV show. (They saved money on the awful Translucent Ghost Kirk floating around the ship, I guess.) “The Mark of Gideon” opened with a hell of a great mystery — Kirk beams down to a planet but never arrives, and we cut to him aboard a completely empty Enterprise — but ended up being about something far less interesting. “The Way to Eden” is about hippies who burn their feet because they don’t wear shoes and Spock sits in for a jam session.

“Requiem for Methuselah” was great until Kirk went mad over wanting to fuck somebody’s robot. “Whom Gods Destroy” had a great scene in which Spock has to figure out which of two Kirks is an imposter, and it had Yvonne Craig, who is hotter than the sun. Actually, we had Julie Newmar last season and Frank Gorshin this season, so the fact that Adam and Burt never showed up is criminal.

“Requiem for Methuselah” was great until Kirk went mad over wanting to fuck somebody’s robot. “Whom Gods Destroy” had a great scene in which Spock has to figure out which of two Kirks is an imposter, and it had Yvonne Craig, who is hotter than the sun. Actually, we had Julie Newmar last season and Frank Gorshin this season, so the fact that Adam and Burt never showed up is criminal.

Speaking of Gorshin, “Let That Be Your Last Battlefield” was obvious and heavy handed, but I’ll be damned if I haven’t been thinking about it regularly in the weeks since I’ve watched it. Unlike “A Private Little War” or “The Omega Glory,” I think the message here actually does benefit from being simple and direct. It’s preachy, but deservedly so.

Speaking of Gorshin, “Let That Be Your Last Battlefield” was obvious and heavy handed, but I’ll be damned if I haven’t been thinking about it regularly in the weeks since I’ve watched it. Unlike “A Private Little War” or “The Omega Glory,” I think the message here actually does benefit from being simple and direct. It’s preachy, but deservedly so.

The writing is a bit flat and the episode suffers from an extended foot chase through the ship’s corridors, but the actual substance of the ending — which, like most of the premise, I won’t spoil — was unquestionably the perfect conclusion to this particular story. It stumbles a bit in the execution, but not at all in its intention. Gorshin is fucking marvelous, and the makeup — while also simple and direct — was impressive. It can’t be that easy to get such a perfect division on a human face.

You know, just thinking again about “Let That Be Your Last Battlefield” makes it grow in my estimation. I wouldn’t rank it among the best in the series, but it’s guileless and sincere in a way that honestly impresses me more than its flaws disappoint me. And I’ll be fucked if its message didn’t hit home in 2021, after the few years we’ve just had.

You know, just thinking again about “Let That Be Your Last Battlefield” makes it grow in my estimation. I wouldn’t rank it among the best in the series, but it’s guileless and sincere in a way that honestly impresses me more than its flaws disappoint me. And I’ll be fucked if its message didn’t hit home in 2021, after the few years we’ve just had.

So season three, to be clear, wasn’t a total write off. It was just frustrating, and frequently so.

There was an interesting (possibly unintentional) theme that I enjoyed, too. Season one felt like a series of what-if scenarios; The Twilight Zone in space, basically. Season two, as we discussed, felt like a longform examination of Kirk, who he is, how far he can be pushed, and what he could become if he isn’t careful. Season three seemed to focus more on other cultures and how they operate.

That is certainly something we explored in the first two seasons, but it was usually in relation to how the Enterprise crew affected or was affected by those cultures. That made complete sense; we have recurring characters for a reason. Here, though, a lot of what the Enterprise crew does boils down to observing, secretly aiding, or attempting to avoid. They often do interfere — what Prime Directive? — but, even then, the story seems to be more about what these cultures are, what they have been, and what they will continue to be.

That is certainly something we explored in the first two seasons, but it was usually in relation to how the Enterprise crew affected or was affected by those cultures. That made complete sense; we have recurring characters for a reason. Here, though, a lot of what the Enterprise crew does boils down to observing, secretly aiding, or attempting to avoid. They often do interfere — what Prime Directive? — but, even then, the story seems to be more about what these cultures are, what they have been, and what they will continue to be.

“The Paradise Syndrome” is about a largely peaceful group of natives who have no idea how close they’ve come to extinction. We learn about who they are, their history, and their customs through Kirk, who becomes a member of the tribe. “Wink of an Eye” is about a group of aliens who move too quickly to be seen by humans, and we explore both the advantages and drawbacks of that kind of existence. “Elaan of Troyius” is entirely about a political alliance that is about to be sealed by a marriage, with the Enterprise acting as little more than a ferry between nations.

“Let That Be Your Last Battlefield” is about a massive civil war that we never see, though we hear about its past and we see what it’s done to two characters caught in its midst. The central conflict in “The Lights of Zetar” revolves around the universe’s invaluable memory banks, records of histories beyond number. (It also, incidentally, features history’s single cutest librarian.) “The Cloud Minders” is about a specific — and quite literal — struggle between a lower and upper class.

“Let That Be Your Last Battlefield” is about a massive civil war that we never see, though we hear about its past and we see what it’s done to two characters caught in its midst. The central conflict in “The Lights of Zetar” revolves around the universe’s invaluable memory banks, records of histories beyond number. (It also, incidentally, features history’s single cutest librarian.) “The Cloud Minders” is about a specific — and quite literal — struggle between a lower and upper class.

So much of season three feels effectively alien, and I love it.

So much of season three feels effectively alien, and I love it.

“The Lights of Zetar,” “Is There in Truth No Beauty?” and “The Tholian Web” all feature major appearances from creatures beyond the understanding of our limited human minds. And we get the inverse as well; there’s a genuinely sad, moving moment in “Is There in Truth No Beauty?” during which an alien possesses a willing Spock, only to be overcome with sorrow for how brief and limited a human life is.

All of this stuff is good, and that’s just a small portion of it. Just about every episode explores a problem faced by a culture that’s going to continue dealing with the fallout of its own decisions long after the Enterprise moves along to its next adventure.

Each episode is like a window into a different show entirely, and I mean that as a compliment. It’s one of season three’s most impressive feats, even if the windows are not created equal.

Each episode is like a window into a different show entirely, and I mean that as a compliment. It’s one of season three’s most impressive feats, even if the windows are not created equal.

I have a feeling that folks who have seen season three have noticed that I haven’t mentioned one particular episode at all.

So…let’s mention it.

When I started this proper journey through The Original Series, I’d already seen a handful of episodes. Those included “Balance of Terror” from season one and “Mirror, Mirror” from season two, which ended up being my favorites from those seasons. I can’t say that I was disappointed by that outcome (they are fantastic episodes of television), but it would have been nice if some other episode I hadn’t seen managed to surprise me instead.

When I started this proper journey through The Original Series, I’d already seen a handful of episodes. Those included “Balance of Terror” from season one and “Mirror, Mirror” from season two, which ended up being my favorites from those seasons. I can’t say that I was disappointed by that outcome (they are fantastic episodes of television), but it would have been nice if some other episode I hadn’t seen managed to surprise me instead.

I hadn’t seen a single episode from season three, though, so I had no idea what to expect, what I liked, or what I didn’t like.

No matter what, some episode would become my favorite of the batch. That could just mean it was the least objectionable one rather than anything that approached the greatness of my favorites from the first two seasons. In fact, I honestly doubted anything would come near those heights, especially as the season wore on and puttered along without steam.

Then, the second-to-last episode of this season (and The Original Series as a whole) hit me like a brick.

Then, the second-to-last episode of this season (and The Original Series as a whole) hit me like a brick.

“All Our Yesterdays” is one of my favorite episodes and my biggest surprise during my little journey. It’s right up there with my two other favorites. It’s not only the best of the season; it’s one of Star Trek’s most magnificent achievements.

Probably coincidentally, each of our three leads this season is faced at some point with the question of where they will end up. Sure, they’re out there zipping around space and flirting with sexy aliens today, but where will they be tomorrow? Everybody ends up somewhere. Where will it be for our heroes?

Kirk raises this question and then ends up trying an answer on for size in “The Paradise Syndrome.” Bones is forced to confront this question in “For the World is Hollow and I Have Touched the Sky,” when he needs to decide if he’s going to spend his final days patching up wounds or enjoying some sort of brief, quiet retirement.

Then we have Spock, who must address the question in “All Our Yesterdays,” and it’s fucking devastating.

Then we have Spock, who must address the question in “All Our Yesterdays,” and it’s fucking devastating.

The episode sees the Enterprise crew heading over to a planet that is on the brink of destruction. They’re there to help, but nobody is around to be helped. The residents of the planet have all evacuated…into the past. Everybody chose a destination, and they escaped tomorrow by heading into yesterday. It’s a neat little sci-fi idea. Our landing party doesn’t quite understand the situation, however, and they end up popping into the planet’s past themselves. First Kirk into one time period, then Bones and Spock into another.

For Kirk, his problem is straightforward. He needs to figure out how to return to the present and reconnect with the rest of his team before the planet goes kaboom.

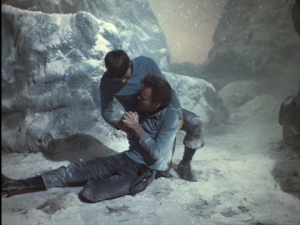

For Bones and Spock, stranded much farther into the past, it’s a different story. They’re stuck in frozen tundra without heat or shelter. Kirk has the relative luxury of being able to think about a solution; Bones and Spock are minutes from death.

For Bones and Spock, stranded much farther into the past, it’s a different story. They’re stuck in frozen tundra without heat or shelter. Kirk has the relative luxury of being able to think about a solution; Bones and Spock are minutes from death.

The whole “people escaping into the past” premise can go a thousand different ways. This is already one very good way.

Then it gets better.

In fact, it gets so good that it hurts.

Bones and Spock are rescued by a woman who never expected to see another person for the rest of her life. She did not evacuate into this time period; she was sent here as punishment for a crime of civil disobedience. It was, essentially, a death sentence.

The more time we spend with her, the easier it is to believe that the punishment was unfair. She’s a good person. She’s a kind soul. She’s caring and friendly. Stranding her in this icy hell was a cruel injustice. She wasn’t sent here to keep her follow citizens safe; she was sent here to silence her.

The more time we spend with her, the easier it is to believe that the punishment was unfair. She’s a good person. She’s a kind soul. She’s caring and friendly. Stranding her in this icy hell was a cruel injustice. She wasn’t sent here to keep her follow citizens safe; she was sent here to silence her.

She’s been stranded here for years with no hope of returning. In fact, everybody who has left for the past has undergone a process that will kill them if they return. For some of them, it’s to keep them from returning to the impending death of their planet. For others, it’s to keep them caged where they are. This is her life; scrounging for food in a world unfit for human habitation, alone, living in misery and dying slowly.

Until she finds Bones and Spock. She rescued them, yes, but their presence has also rescued her. She is no longer alone. She has companions who can help. Friends. Maybe, in Spock, a lover. Someone to care about and to be cared about by.

This actor, Mariette Hartley, is so gentle, and has such kind eyes, and is so clearly stuck here unfairly, that it’s impossible not to feel strongly for her character. For her predicament. For her very real damnation at the hands of a society that has not thought about her since the moment she was banished forever.

This actor, Mariette Hartley, is so gentle, and has such kind eyes, and is so clearly stuck here unfairly, that it’s impossible not to feel strongly for her character. For her predicament. For her very real damnation at the hands of a society that has not thought about her since the moment she was banished forever.

And Spock, unable to find any way back to his captain, or even out of the past, begins to consider a life here. With her. Helping her grow crops and stay safe. Speaking with her. Exchanging stories of completely different worlds and histories. The episode gives his Vulcan impulses a reason to regress, but I don’t believe they’re necessary; Spock feels love, he feels fear, he feels happiness, he feels sorrow, as much as he wished he didn’t. Realizing that he’s stuck in a hopeless world, he’s going to experience a lot of emotions, and they are not going to be pleasant. Realizing further that he’s at least stuck with…well…Mariette Hartley, he’s going to experience even more emotions.

The man’s internal conflict ramps up over the course of the hour to the point that it seems like he is losing his mind. It’s real and it’s sad and it’s even a little scary.

When Kirk manages to find a way to reunite the trio, Spock is faced with the very real dilemma of having to choose between two futures. Does he return to his captain and live that life, or does he stay here and live this one? His choice is soon taken from him, in an even sadder swing of the hammer; since he and Bones slipped into the past together, they can only escape it together. If he stays here, he’s robbing the good doctor of his future. As such, he is obligated to return. A choice between two futures has suddenly become one entire future snatched away before his eyes.

When Kirk manages to find a way to reunite the trio, Spock is faced with the very real dilemma of having to choose between two futures. Does he return to his captain and live that life, or does he stay here and live this one? His choice is soon taken from him, in an even sadder swing of the hammer; since he and Bones slipped into the past together, they can only escape it together. If he stays here, he’s robbing the good doctor of his future. As such, he is obligated to return. A choice between two futures has suddenly become one entire future snatched away before his eyes.

And poor Mariette Hartley, who against all possibility found companionship in the wasteland — with intelligent, friendly people — is left alone again. How much more must it sting, to have to adjust a second time to being alone. How much pain must now follow that brief window of relief. How much sorrow must she feel, knowing that she had what she could not keep.

It’s — again — fucking devastating, and the episode plays it perfectly. In “The City on the Edge of Forever” we similarly met a doomed love interest, but that love interest was always doomed. Joan Collins died in the timeline in which she didn’t meet Kirk, and she died in the timeline in which she did. Nothing really changed except for the fact that Kirk (and we) got to know her. That’s why it hurt. She wasn’t a name in the obituaries; she was a person. In all truth, she was no worse off for the experience, however sad and upsetting her end might have been to us.

Mariette Hartley is worse off. She had adjusted, she had her adjustment shattered, and she was left alone to adjust again. Only this time in more pain, more hopeless, with memories of another, more recent loss.

Mariette Hartley is worse off. She had adjusted, she had her adjustment shattered, and she was left alone to adjust again. Only this time in more pain, more hopeless, with memories of another, more recent loss.

I love “All Our Yesterdays.” And if Star Trek had ended just one episode sooner than it had, this would have been the final chapter of The Original Series. What a perfect way to go out. Instead we got “Turnabout Intruder,” and the nicest thing I can say about that episode is that watching it didn’t make all of my teeth fall out.

And so that’s it for season three, and for The Original Series. Without question, I enjoyed it. But I expected that. I expected highlights and lowlights. I expected to laugh with the show and at the show at different times. I expected that there would be moments and episodes that impressed me.

But it was also a journey full of surprises, and none of those was bigger or more appreciated than “All Our Yesterdays,” which ripped my heart out and stomped on it in a way that impressed the hell out of me.

But it was also a journey full of surprises, and none of those was bigger or more appreciated than “All Our Yesterdays,” which ripped my heart out and stomped on it in a way that impressed the hell out of me.

Season three was rough going much of the time, but there were still moments that reminded me of why Star Trek was adored in the first place. And there was one episode that would have justified an entire season of “Spock’s Brain.”

Speaking of which, here is every “Spock’s Brain” ranked from worst to best. And please, let me know your favorites from this or the previous seasons. Discussing the show here has been great fun, and I thank you for joining me on this long-overdue trip.

24) Plato’s Stepchildren

23) The Empath

22) The Way to Eden

21) The Savage Curtain

20) Spock’s Brain

19) Turnabout Intruder

18) Whom Gods Destroy

17) And the Children Shall Lead

16) The Mark of Gideon

15) Requiem for Methuselah

14) The Cloud Minders

13) That Which Survives

12) Wink of an Eye

11) The Tholian Web

10) Elaan of Troyius

9) Let That Be Your Last Battlefield

8) The Lights of Zetar

7) The Paradise Syndrome

6) Spectre of the Gun

5) The Enterprise Incident

4) For the World is Hollow and I Have Touched the Sky

3) Day of the Dove

2) Is There in Truth No Beauty?

1) All Our Yesterdays

Images throughout courtesy of Warp Speed to Nonsense.