I’ve been meaning to do something like this for a while. I’ve always been something of a collector of books (which is a polite way of saying it’s the one thing I’m liable to hoard), but as much as I love and respect them, I don’t usually bother to track down rare editions of anything. If I find them, great…but even then there’s no guarantee I’ll buy them. I just look at them, afraid to hasten their decay with whatever oils and greases are bound to be on my fingertips, afraid even to stare too long lest that be the moment I discover I am capable of pyrokinesis.

But once I fell in love with Thomas Pynchon, that changed. At least, as far as rare editions of Thomas Pynchon books are concerned. Over the years I’ve built a collection I really enjoy, and if there’s interest maybe I’ll share more of it later on. But for now, I just wanted to go through his brief bibliography, show off some very poor photos of the first edition hardcovers I’ve acquired, and talk briefly about them.

If you want to know more about what these books are actually about (what a concept!) you can check out my Thomas Pynchon Primer. This is really just a chance to look at some things that I think happen to be pretty cool.

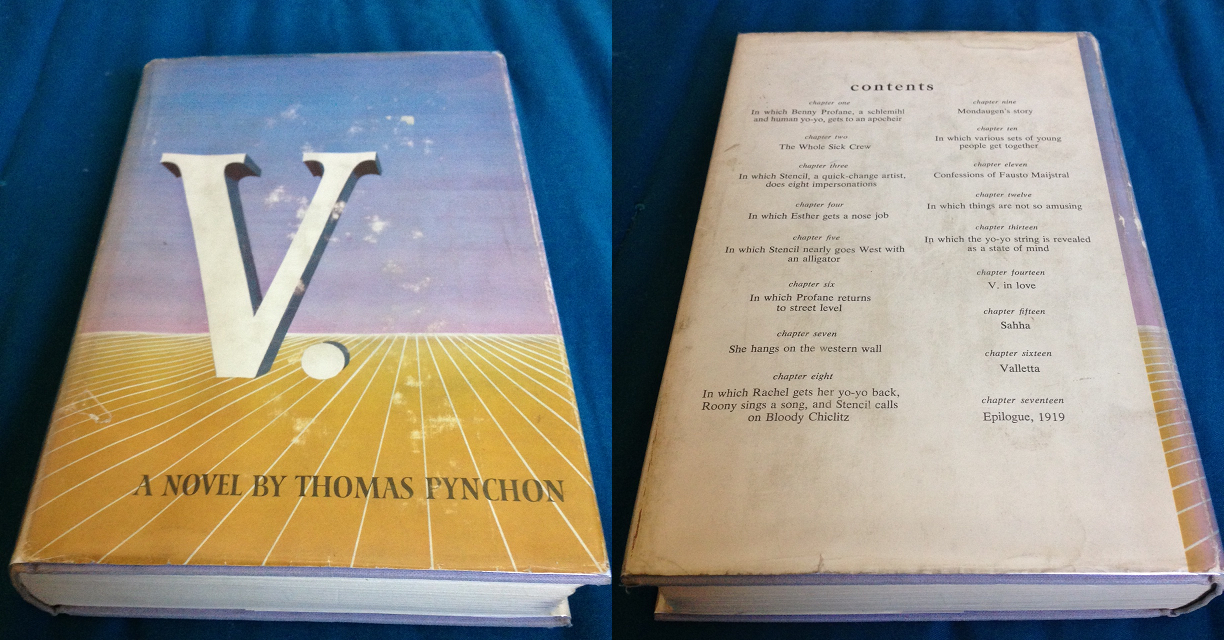

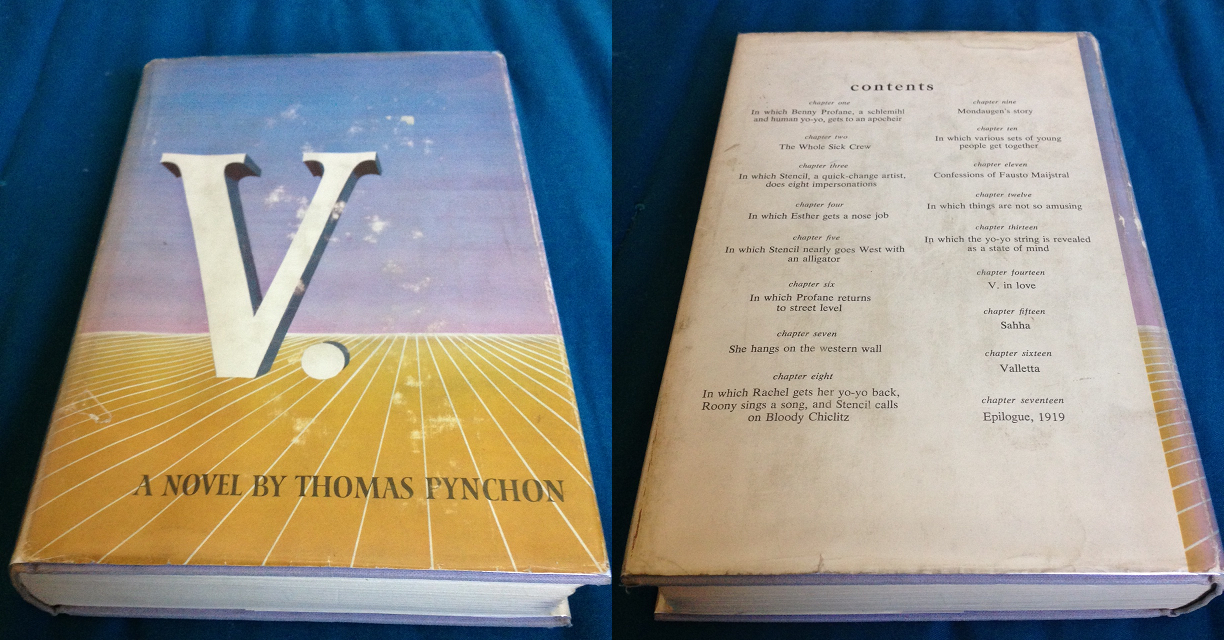

V. was published in 1963, when even fewer people knew who Thomas Pynchon was than do today. I bring that up because it’s certainly the reason my first edition of the book isn’t in such stellar shape. As you can see, there’s some significant wear and scuffing on the front cover, and some discoloration on the back. But it could be far worse, and I’m not complaining.

Finding a better looking copy of V. won’t be easy. As his first book, I’m sure very few people cared to preserve it. Outside of private collections of people who knew him personally, the odds are that surviving copies of the first printing bear the marks of being crammed into backpacks, dropped carelessly, or having things spilled on them. That is to say, people treated it like a book rather than a collector’s item, which, at the time, it was. This copy is the best I’ve seen in person. Potentially I’d upgrade, but the odds of finding a better one seem pretty slim.

One thing that I really like about this cover is the back. As you’ll see, publishers never really figured out what to do with Pynchon’s back covers, but I like the way they experimented with V. the best. There’s no real value to having chapter titles on the back of a closed book, but in a novel as dizzying as V., any help with orientation is bound to be appreciated. It’s also a very efficient way of introducing new readers (as they all would have been, then) to the author; those titles do a great job, I feel, of conveying the way in which he writes. His approach, variety, and interests (and seeming conflicts and confusions) are all laid out right there.

Later Pynchon books would miss out on this back cover matter…but they’d do so out of necessity. V., after all, is the only novel in which Pynchon titled his chapters. FUN FACT.

Also, another FUN FACT: this edition of V. contains different text from all later printings. The reason is that Pynchon changed his mind about a few things after it went to the printer. It’s not uncommon for spelling or formatting errors to be corrected in later printings, but in this case they were actually rewritten passages. Oddly, this unique text wasn’t discovered until just a few years ago, when Pynchon’s novels were being prepared for release as ebooks. Due to the rarity of first edition copies, and the fact that nobody expected anything different there, decades worth of scholarship missed the fact that the V. we were reading wasn’t V. as it was originally published. Neat.

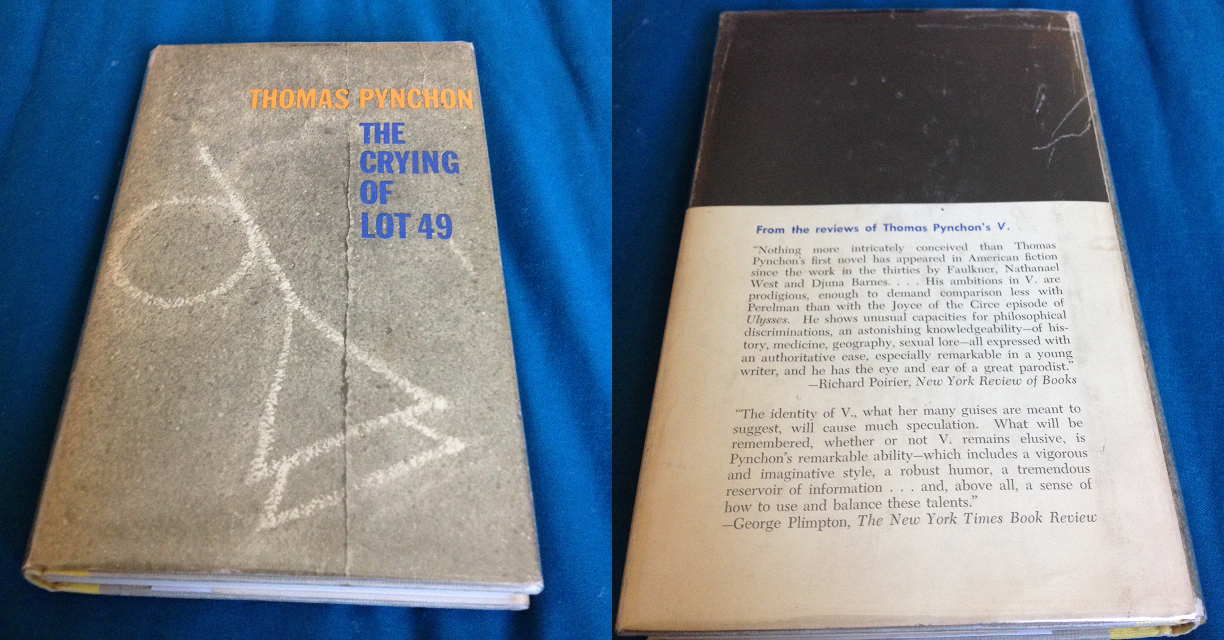

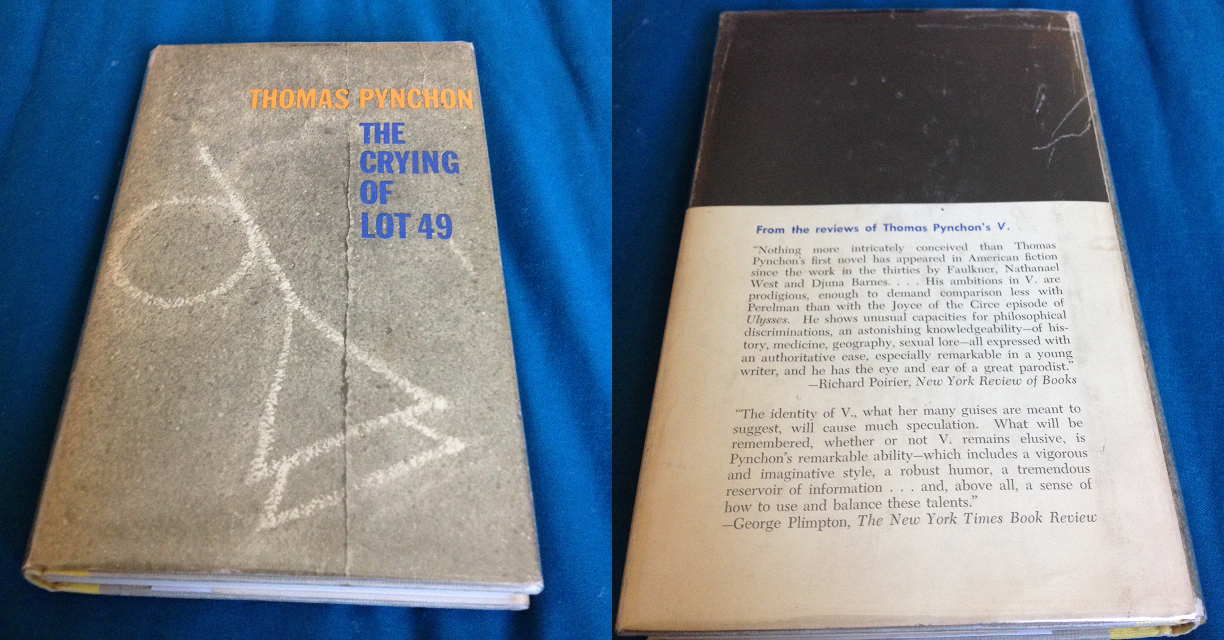

In 1966, Pynchon published The Crying of Lot 49. It’s a glorified novella in terms of length, but not — I’d argue — in terms of depth. My front cover is in better shape than one might think; the artwork makes it difficult to tell. But the back cover definitely betrays some wear and tear.

On the cover we see a sketch of a muted post horn, which is an important symbol in the story and is also the novel’s sole illustration. (It also provided the design for my tattoo.) On the back we have excerpts from the reviews for V., another back-cover idea that was never used again…perhaps because Pynchon’s reviews are notoriously mixed, but more likely because between V. and The Crying of Lot 49, his name began to carry significant cachet, and it became less important to “convince” people that he was worth reading.

I actually acquired this first edition copy twice. Yes, the same exact copy. A few years ago, my girlfriend at the time bought it for me as a Christmas gift. It was — and will certainly always be — one of the best possible gifts I could receive. But I didn’t want to read it…I wanted to display it on a shelf. My motives for this were obvious, I think; the last thing I’d want to do with a piece of literary history like this is put myself in a position to destroy it. But she took my reluctance to handle it too much as dissatisfaction with the gift.

She took it back. Merry Christmas to all. And that was the last I saw of it for years, until well after we broke up. The rare book store we both visited when we were together called me and told me they’d just gotten a very good first edition of The Crying of Lot 49 if I was interested. They knew I was, of course, and they did everything they could to make it clear, without saying it, that it was the same copy she’d bought for me in the first place. So I went and bought it myself, and I made sure to show me the proper appreciation for it so I wouldn’t have it taken away again.

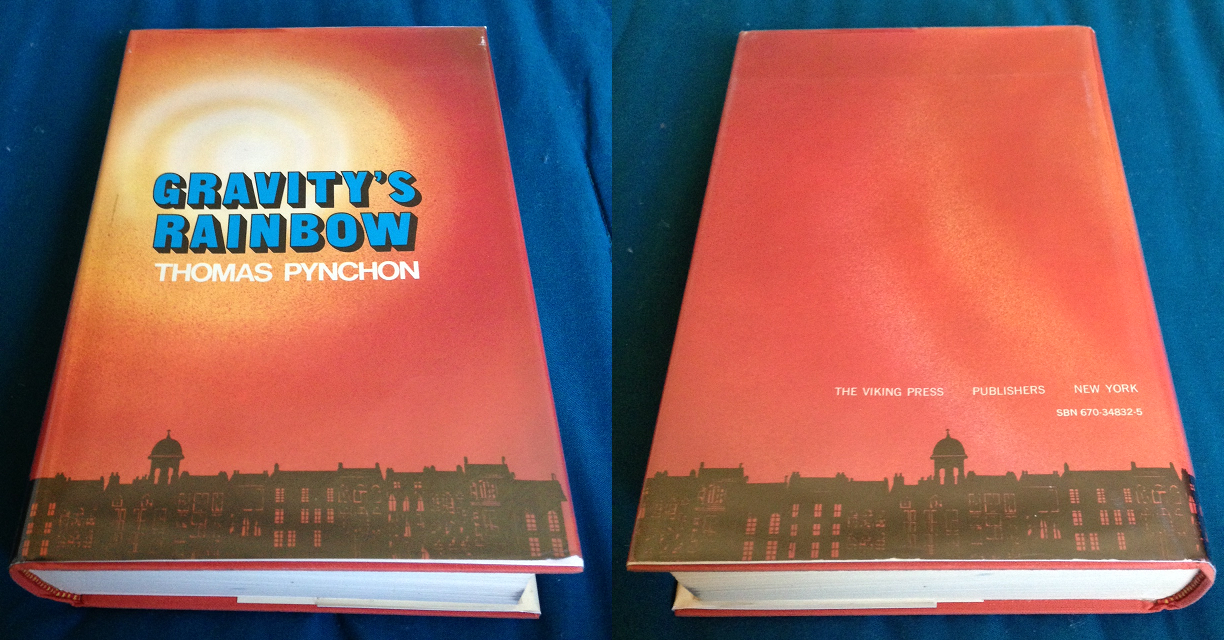

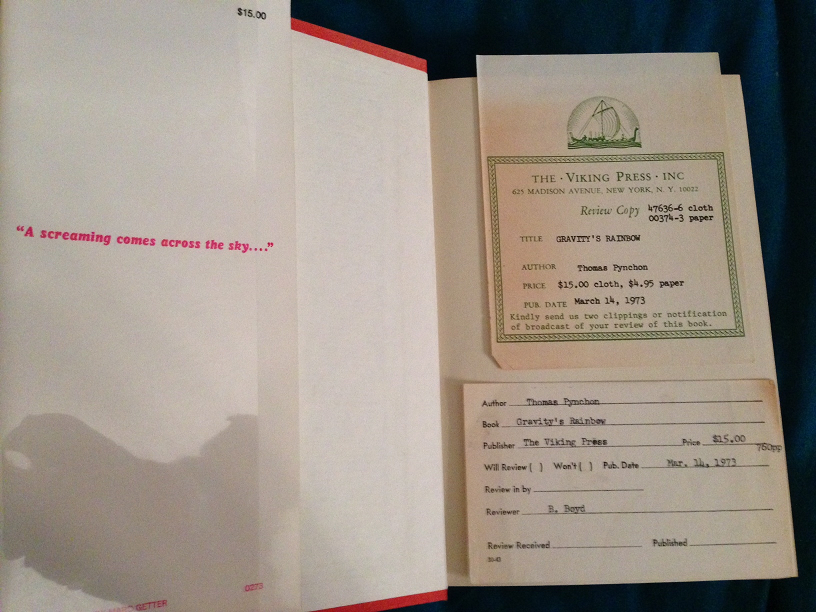

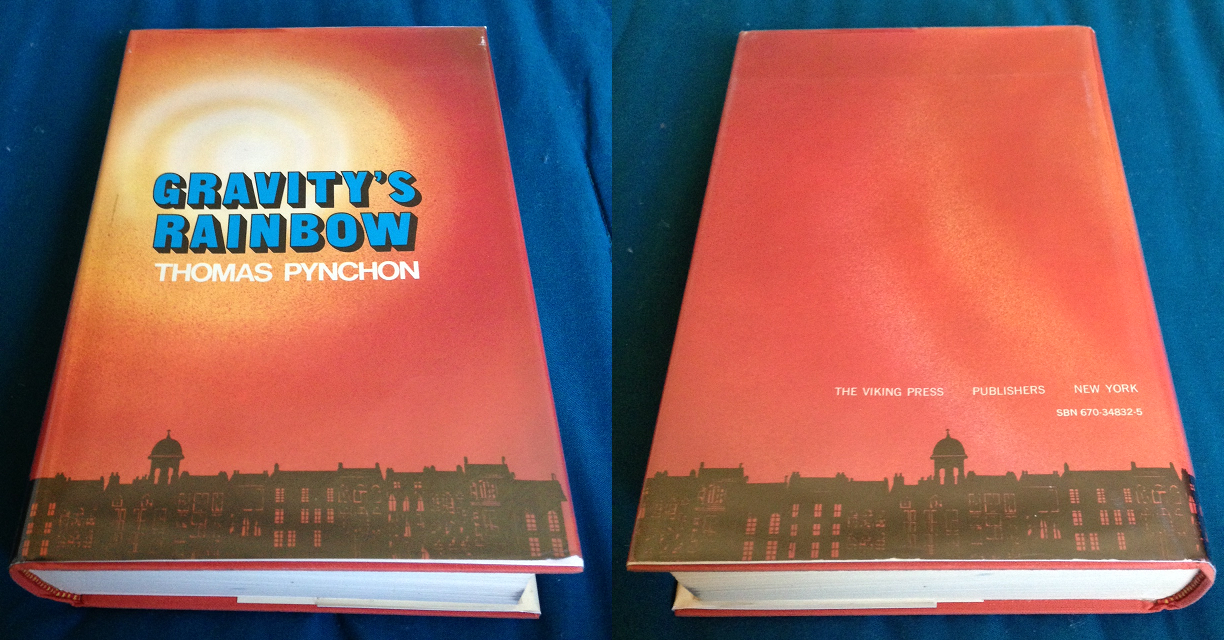

Now this…this is the one I never expected to own. Gravity’s Rainbow (1973) got a larger printing than both of Pynchon’s previous titles, so scarcity isn’t the issue so much as the fact that this is the Thomas Pynchon novel. Rare copies demand high prices, because this is the one people — fans, collectors, resellers — want most.

I had a chance to spring for a first-edition paperback, and passed it up…something I was pretty regretful of for a while. But eventually I was at my favorite rare book store and asked if they had any copies.

They did…and they kept it in the back, where nobody could muck it up with their grubby hands. It was gorgeous; on the upper right of the front cover it may look like there’s a bit of damage, but it’s actually just glare from the plastic dust jacket I use to keep it in good shape. It’s quite lovely, really.

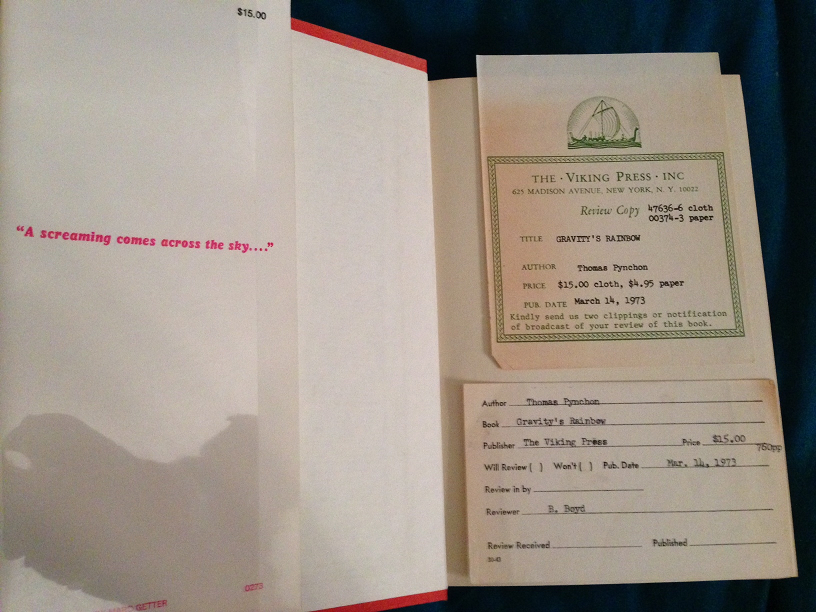

The best thing, though, is this:

This isn’t just a first-edition hardcover…it’s a review copy. This was sent to some magazine or newspaper reviewer with the materials you see here. (They are loose; I arranged them here for the photo but they’re not attached in any way to the book itself.) As you’ll also see, the reviewer never did his or her job. This is a copy mailed out ahead of general release…that sat on a shelf somewhere, was moved to an archive, and was likely never even read. It’s one of the first printed copies of the novel period, and I’ve never seen another copy with the review request materials. For all I know, these are the only ones that survive.

Oh, and it’s my favorite novel of all time so THERE’S THAT.

It’s also the most expensive thing I’ve ever purchased, outside of any cars I’ve owned, so if you break into my house and want to get out with something quick, go for this. It’s small and worth a lot more than any of the other crap you’ll see lying around.

The back cover sets what’s pretty much the closest thing to a precedent Pynchon’s back covers would ever have: an uninterrupted continuation of the front cover’s artwork. It’s pretty beautiful.

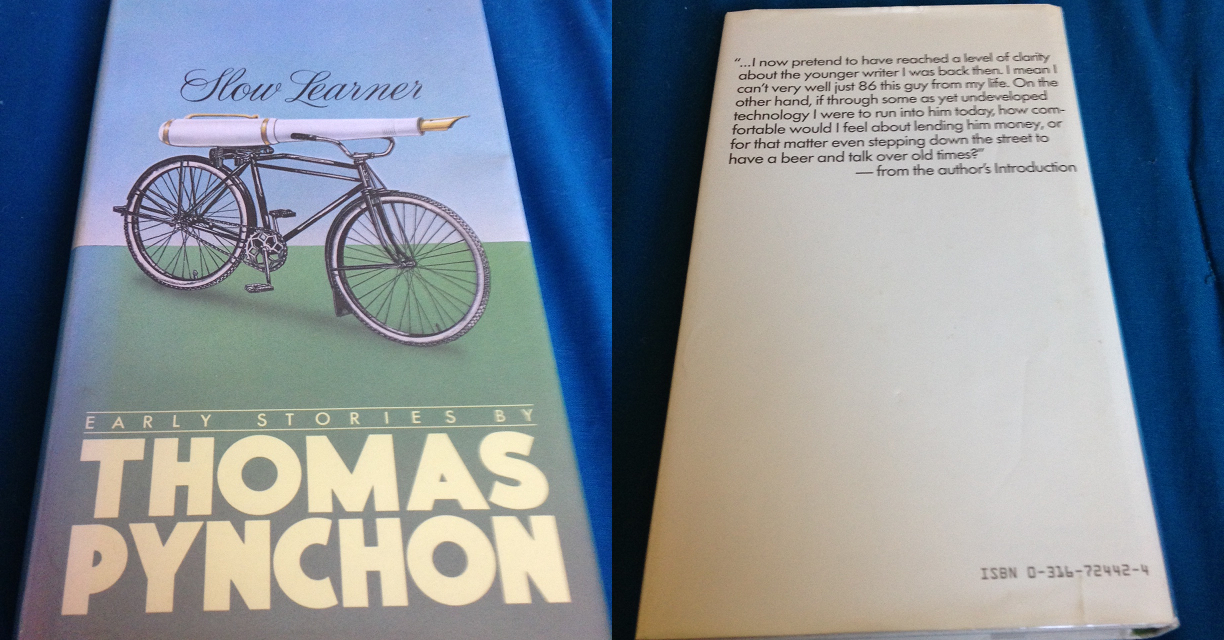

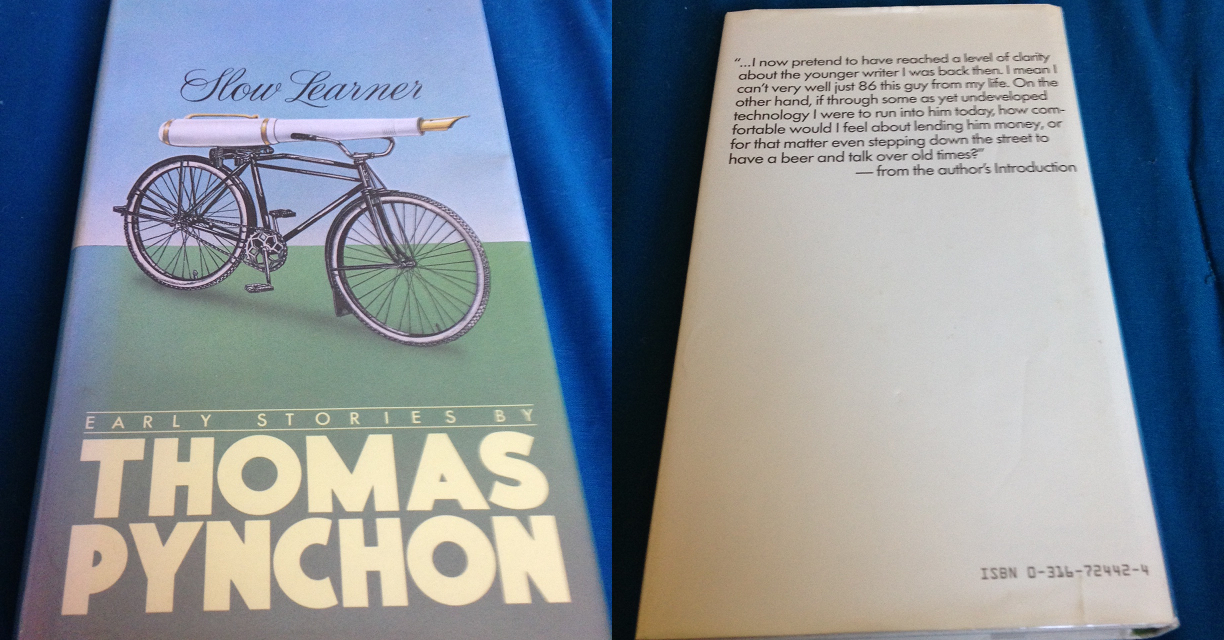

In 1984, eleven years after Gravity’s Rainbow, Pynchon finally published something: a collection of other things he already published.

Slow Learner isn’t that great; as a reading experience, you’d be hard pressed to do much worse. As a slow study of a young artist becoming a legendary one, though, it’s unparalleled.

I’ve mentioned before that some copies of Slow Learner are reported to contain a sixth story: “Mortality and Mercy in Vienna.” I’ve found copies of that story, but never a version of this book that contains it. And since this is a first edition, I don’t know where else to look. It’s possible that it was only included in printings released in other countries, but I’ve never found specific information about that, and part of me suspects it’s just false information that’s been propagated over time.

The back cover in this case includes an excerpt from the book…specifically, the author’s introduction.

By this point Pynchon had only released three novels, but his reluctance to speak about himself, make public appearances, provide interviews, or do anything else that established writers were supposed to do meant that a huge part of Slow Learner‘s value came from the brief introduction Pynchon provided. Spotlighting it here meant that people wouldn’t miss its inclusion, and, certainly, it still stands as the book’s highlight.

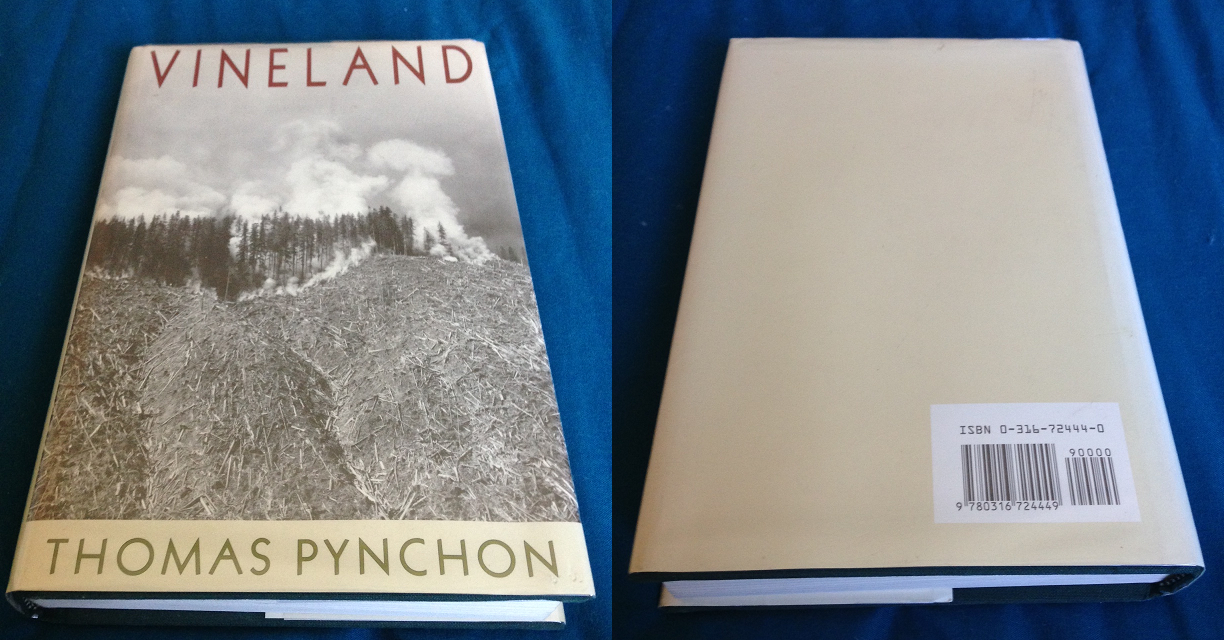

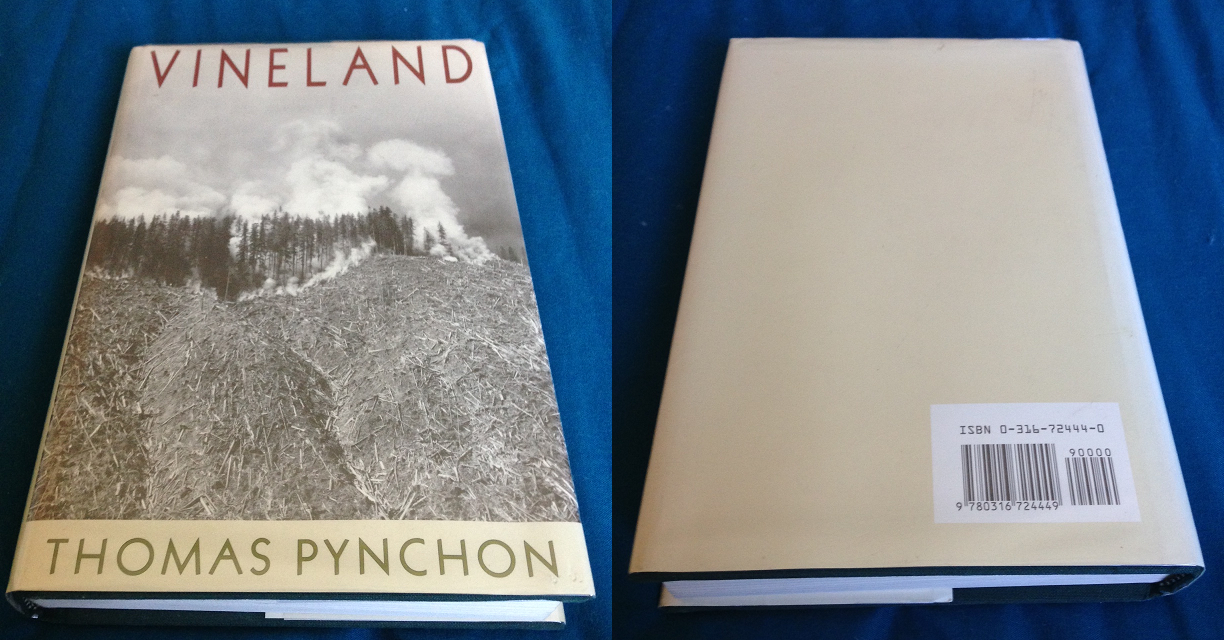

Unlike the above, Vineland is fairly easy to find as a first edition. In fact, I think this one set me aside around $20, and it’s in gorgeous shape. I think the reason for this is that by its publication in 1990, Pynchon’s reputation had grown so much that it was guaranteed to get a huge printing…and the mixed to negative reviews that met its release meant that a lot of them were left unsold.

Personally, I don’t know why anyone could read Vineland and come away feeling negative about it. It’s one of my favorite Pynchon novels, and, yes, a wait of almost 20 years after Gravity’s Rainbow probably helped people set their expectations too high…but, damn. What a bunch of crybabies.

Oh well. It resulted in me getting this very inexpensively, and I’m sure you can find one around that price, too.

The critical reception to Vineland stings in a way that I can’t really articulate. I think I just hate the fact that I live in a world in which something of such strong literary merit is met with a shrug because it’s not whatever illusory thing people decided they wanted instead. Artistic entitlement is such an awful thing.

The book, though, is in pristine shape. The back cover features a bar code. A BOLD CHOICE.

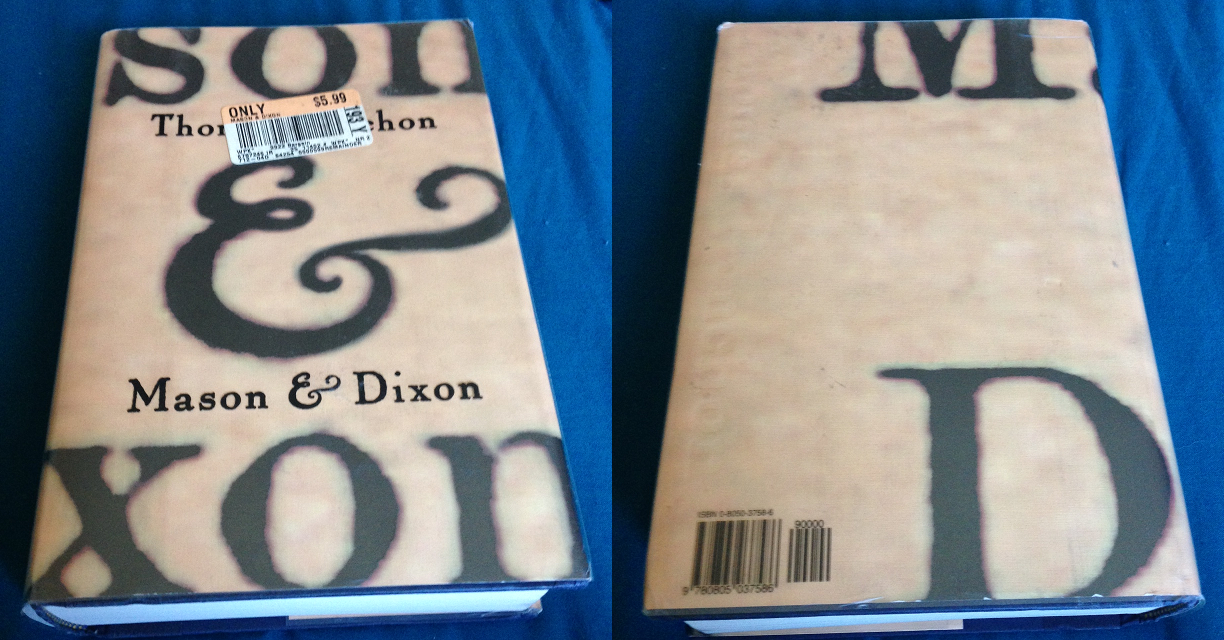

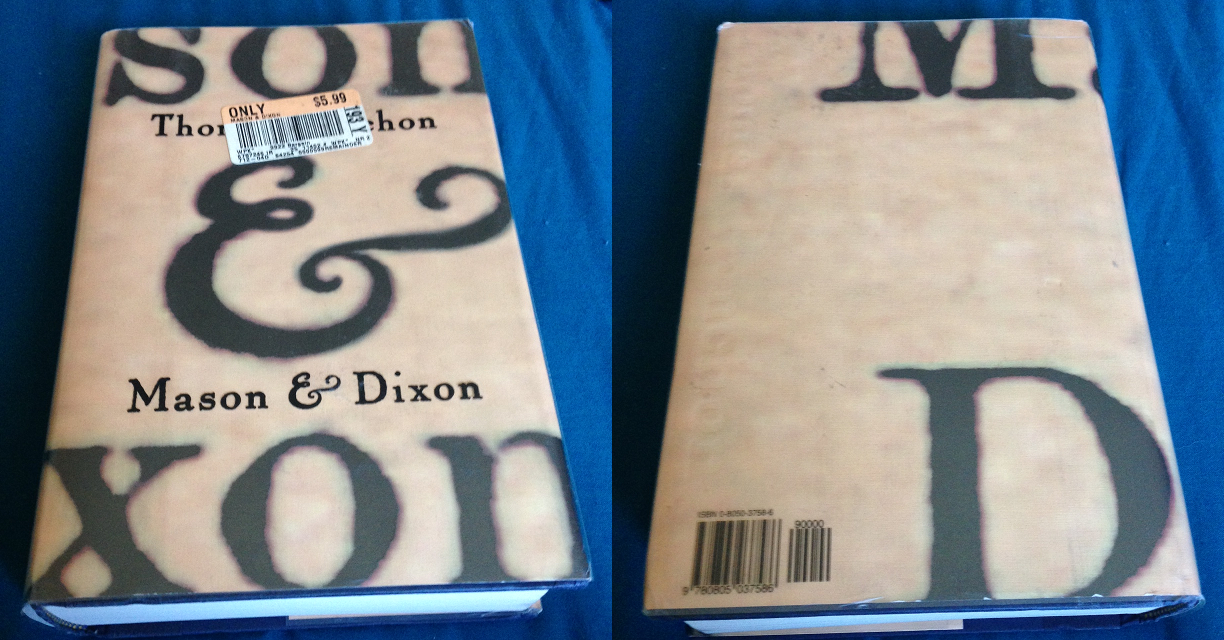

From here on, we get to the first editions that I actually bought upon release.

Or, kind of. Mason & Dixon came out in 1997, but I don’t think I bought mine until 1999 or so. I wasn’t a Pynchon fan at the time, but it was on an overstock table at Borders, as you’ll see from the price tag.

I bought it, read it, and hated it with a passion. Now I think it’s a remarkably warm and profound book that I revisit every couple of years, so…yeah, sometimes it’s worth persevering with things you don’t at first understand.

The price tag is still on it because I don’t want to remove it without damaging the book. Granted, it’s on a dust jacket, but that dust jacket isn’t entirely transparent…the words “Thomas Pynchon” and “Mason & Dixon” are printed on it.

Of course, since I bought this before I was a collector there’s quite a bit of shelf-wear and a few dings, so it’s not like it’s in the best of shape anyway, but I still haven’t risked removing the tag. Maybe part of me just really misses Borders.

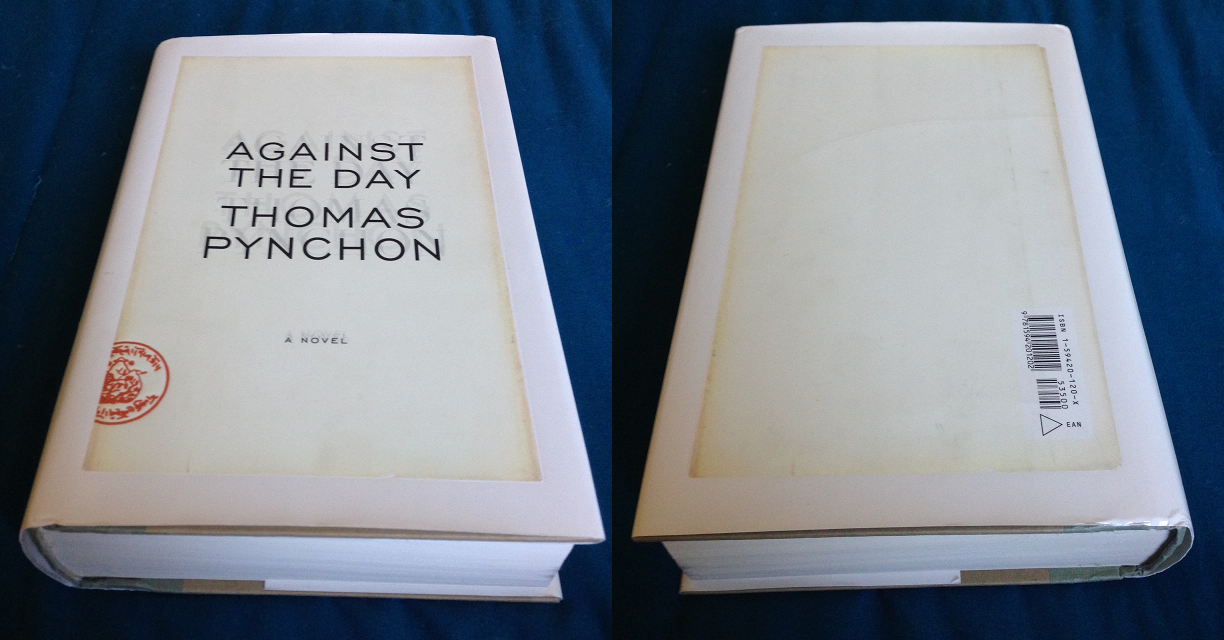

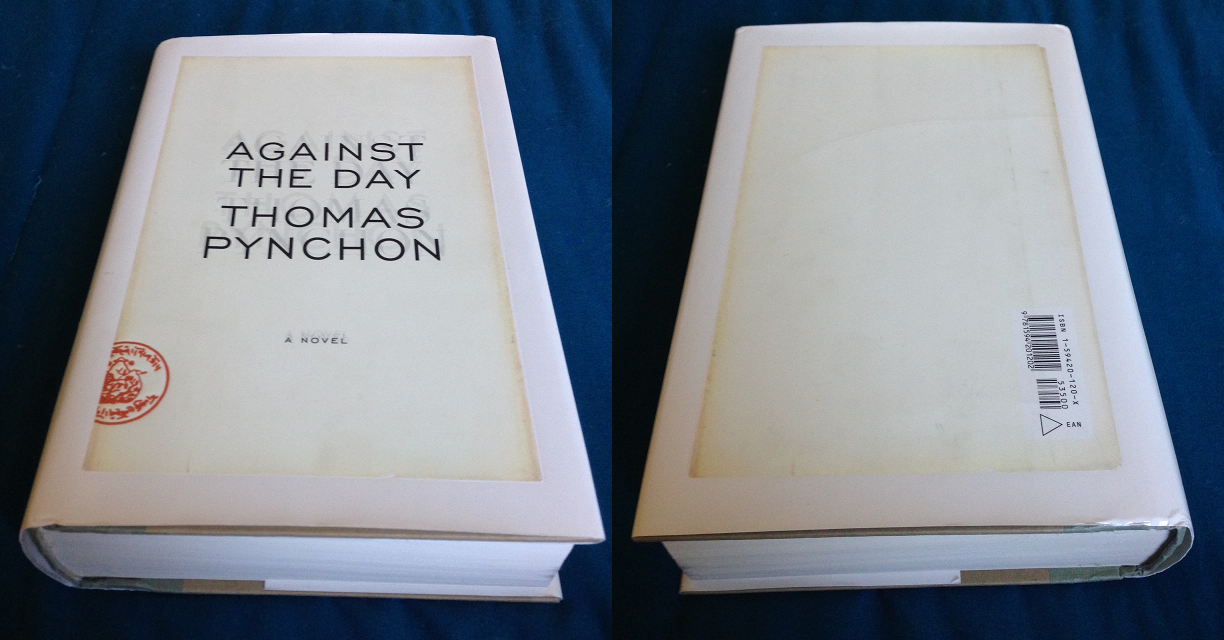

I can’t get too upset at the first-day Vineland haters, because I had a similar (if not nearly as strong) reaction to Against the Day when it came out in 2006. I’ve warmed up to it since, but it still feels a bit overlong…like it could do with a reduction of a couple hundred pages easily.

That’s not to say it’s without charm, though, and I re-read it recently and found more reasons to love everything I initially loved, and a few new reasons to love some of the things I originally overlooked. It’s by no means Pynchon’s best…but it’s an experience I know I’ll return to many times.

My copy is in pretty good shape!…is what I would have said before taking these photos. Now I see a pretty nasty scratch across the back cover. I have no idea what that’s from, but it’s a good reminder to be careful. Fortunately I’m sure I could find another copy; for now I’m okay with it, but in the future I have a feeling that proof of carelessness is going to drive me insane.

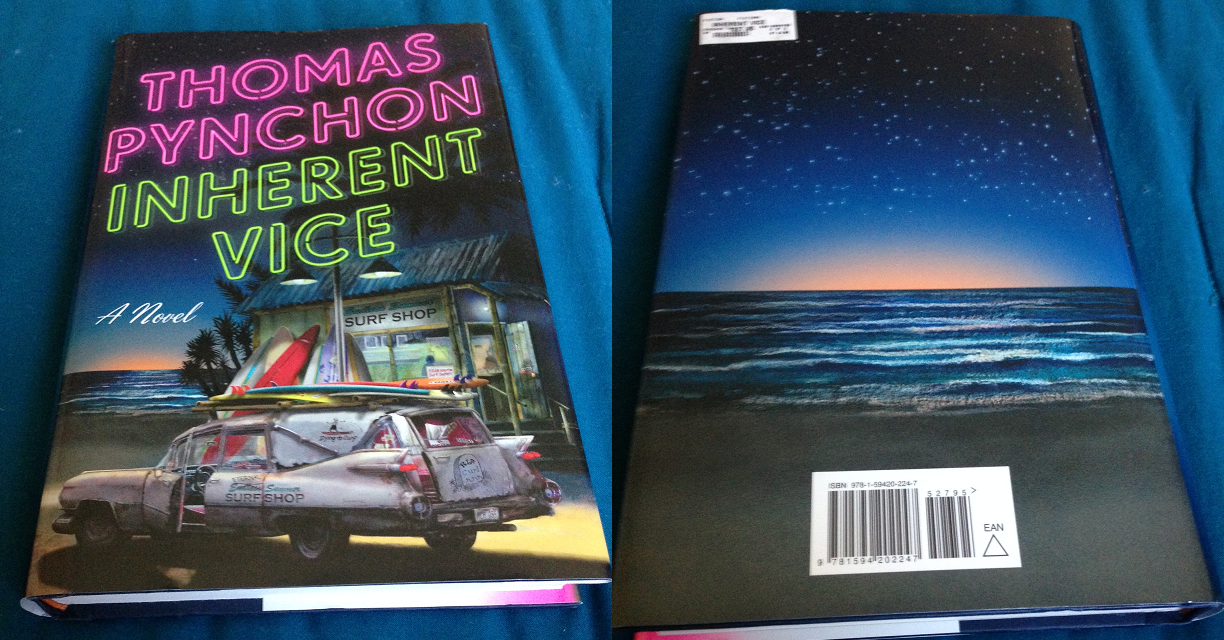

I bought Inherent Vice the day it was released in 2009. It feels like a lifetime ago. I was a different person then, in a very different place in life. I won’t get into any of that, but I know I read through this exact copy multiple times I was recovering from a surgery. It was this and Neil Young’s Heart of Gold concert DVD that kept me the most — and best — company.

This one is still in very good shape, even if the back cover still has a price tag and I can’t take a non-blurry picture to save my life. I’d like to be able to say that any first editions I buy as an adult are guaranteed to remain gorgeous and pristine, but the fact is that I like to read them. Wear and tear is the cost of enjoying what you collect, I guess.

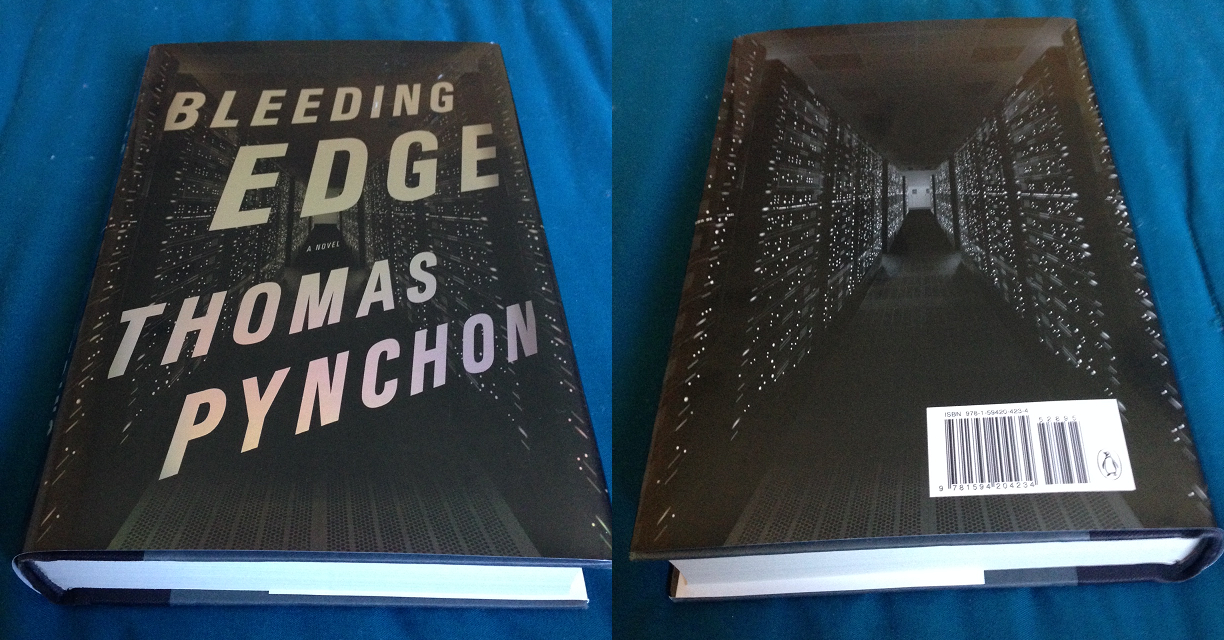

And, finally, 2013’s Bleeding Edge. No great stories about this one (I drove to the bookstore after work and bought it!), but I guess I did cross some kind of ethical line. After I’d purchased it, but before I left the store, I noticed damage to the dust jacket, so I EXCHANGED IT WITH ANOTHER COPY WITHOUT TELLING ANYBODY. I hope the statute of limitations is up on that crime, because if there’s one kind of prisoner that gets it rough, it’s the book swapper.

As of right now, that’s Pynchon’s most recent book. It might end up being his last, but I’ve been saying that for the past three books, so maybe I’ll just wait and see rather than convince myself that my favorite author is as good as dead.

So, that’s my tour of my first-edition hardcovers of Thomas Pynchon. A complete set, and there’s something truly comforting and rewarding about looking over at that shelf and seeing a small piece of literary history. It’s humbling…especially for a guy who writes about ALF.

Choose Your Own Advent is a yuletide celebration of literacy. We’ll spotlight a different novel every day until Christmas, hopefully helping you find one you’d like to read in the new year.

Choose Your Own Advent is a yuletide celebration of literacy. We’ll spotlight a different novel every day until Christmas, hopefully helping you find one you’d like to read in the new year.