I’m a barber’s son.

When it came time for me to decide which film to spotlight for Wes Anderson month, I found it to be a pretty difficult decision. I could easily have turned to personal favorites The Royal Tenenbaums and The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou and rattled for a few thousand words about why I think they’re great. Or I could have done a piece about why The Darjeeling Limited feels like Anderson catching himself off guard, with mixed — though ultimately excellent — results. And, of course, I could have written a piece about either Bottle Rocket or Fantastic Mr. Fox, giving myself an opportunity to explore critically my misgivings.

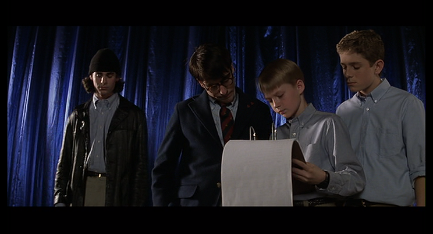

But all of that would have been almost too easy, especially when, all month long, Rushmore has been calling out to me, and attempting to instill itself in my mind as the perfect ambassador of Anderson’s form and methods. Eventually, I caved to its charm and confidence, and accepted what it told me wholesale. Rushmore positioned itself so effectively in my mind the same way Max Fischer positions himself so effectively in the film: by already believing itself to be right. That’s also how Anderson, at his best, manages not only to overcome contrived situations and wooden performances, but to harness their dormant energy and ultimately use them to his creative advantage. It’s a whole lot of charm, a larger amount of confidence, and a willingness to invest absolutely everything. Rushmore embodies all of that perfectly.

But all of that would have been almost too easy, especially when, all month long, Rushmore has been calling out to me, and attempting to instill itself in my mind as the perfect ambassador of Anderson’s form and methods. Eventually, I caved to its charm and confidence, and accepted what it told me wholesale. Rushmore positioned itself so effectively in my mind the same way Max Fischer positions himself so effectively in the film: by already believing itself to be right. That’s also how Anderson, at his best, manages not only to overcome contrived situations and wooden performances, but to harness their dormant energy and ultimately use them to his creative advantage. It’s a whole lot of charm, a larger amount of confidence, and a willingness to invest absolutely everything. Rushmore embodies all of that perfectly.

After all, Rushmore itself is a movie about manipulation, and I mean that in both the constructive and reductive senses of the word. Max Fischer is seemingly a 15-year-old omni-prodigy, though he doesn’t happen to be particularly good at anything. Or, perhaps, he’s not particularly good at anything other than manipulating people into thinking he’s good at things. It’s enormously telling — and appropriate — that the only thing that earns Max any genuine accolades throughout the course of the film is his work as a playwright.

Writing and directing plays allows him to work with his most effective resources: the tools of manipulation. Every line spoken, every step taken, every lighting decision and element of background animation are within his control, and that’s how he likes it. By default, Max is not easily shaken. Upon given notice that he’s being placed on sudden-death academic probation and may be kicked out The Rushmore Academy, he responds coolly and attempts to strike a reasonable bargain to remain enrolled. By contrast, when one of his actors fails to deliver a minor line in his stage adaptation of Serpico, Max becomes emotional, aggressive, and instigates physical violence.

Plays are where Max feels the most control, and they’re where he can rely on retaining that control. As evidence, it’s no coincidence that his assemblage of actors go under the name The Max Fischer Players. These are Max’s projects, in his hands and under his control, and if anything threatens his complete dominion over them he feels threatened, and he will lash out.

Plays are where Max feels the most control, and they’re where he can rely on retaining that control. As evidence, it’s no coincidence that his assemblage of actors go under the name The Max Fischer Players. These are Max’s projects, in his hands and under his control, and if anything threatens his complete dominion over them he feels threatened, and he will lash out.

It’s also no coincidence that hands are a recurring motif in Rushmore. In fact, the film is largely — arguably entirely — about Max’s relentless manipulation of the world around him. Interestingly, the word “manipulate” itself derives from the Latin manus, which means hand. Manipulating means literally to position by hand. The word “manufacture” shares a similar original, meaning to create by hand, and both “manipulate” and “manufacture” feel like inextricable parts of Max’s daily routine. (The Latin connection is also a pleasant surprise when considering this within the context of the film.)

All of this goes to justify and explain the film’s compulsive interest in hands, and what one can do with them. Perhaps most overtly, Max lies about receiving a handjob from Mrs. Calloway, the mother of his chapel partner Dirk, which is an interestingly specific fabrication. Handjobs also factor into Dirk’s deliberately needling letter to Max later in the film, when Dirk claims he witnessed Miss Cross and Mr. Blume giving them to each other. The comedy comes from the fact that Dirk clearly doesn’t know what a handjob is — they’re rather necessarily one-sided in heterosexual relationships — but when Max believes it, he reveals that he doesn’t know either. It’s something that sounded appealing to Max, and its emphasis on handiwork — so to speak — fits in perfectly with his personal ethos, and lent itself to a thematically fitting lie.

All of this goes to justify and explain the film’s compulsive interest in hands, and what one can do with them. Perhaps most overtly, Max lies about receiving a handjob from Mrs. Calloway, the mother of his chapel partner Dirk, which is an interestingly specific fabrication. Handjobs also factor into Dirk’s deliberately needling letter to Max later in the film, when Dirk claims he witnessed Miss Cross and Mr. Blume giving them to each other. The comedy comes from the fact that Dirk clearly doesn’t know what a handjob is — they’re rather necessarily one-sided in heterosexual relationships — but when Max believes it, he reveals that he doesn’t know either. It’s something that sounded appealing to Max, and its emphasis on handiwork — so to speak — fits in perfectly with his personal ethos, and lent itself to a thematically fitting lie.

Miss Cross also invokes the concept of a handjob when she asks Max what he’d tell his friends if they did sleep together. She also asks whether or not he’d claim that he fingered her…another clearly (and more accurately phrased) reference to his hands in a sexual sense.

Less obscenely, Max uses his hands to make statements that he cannot — or chooses to not — make through his words. He orders a construction crew to shut down by gesturing to them, he signals to a disc jockey to play a song he’s selected specially for the occasion, and he flashes Dr. Guggenheim the middle finger after starting a fire outside of his office window. For an artist, particularly one who engages regularly in strongly physical extra-curricular activities, the hand can be as expressive or more expressive than the voice. Even his handwriting is deliberately considered and executed, with a careful calligraphy employed even his least formal note taking.

Less obscenely, Max uses his hands to make statements that he cannot — or chooses to not — make through his words. He orders a construction crew to shut down by gesturing to them, he signals to a disc jockey to play a song he’s selected specially for the occasion, and he flashes Dr. Guggenheim the middle finger after starting a fire outside of his office window. For an artist, particularly one who engages regularly in strongly physical extra-curricular activities, the hand can be as expressive or more expressive than the voice. Even his handwriting is deliberately considered and executed, with a careful calligraphy employed even his least formal note taking.

Max’s hands serve as a clear symbol of who he is, and of what he does. That’s why when Dirk refuses to take his hand after a school-yard scuffle, it’s much more clearly a rejection of who Max is as a person than a simple — though loaded — refusal to help him up. Dirk eventually apologizes for not taking his hand, and Max, in the same conversation, apologizes for claiming that his mother gave him a handjob. A hand caused both insults, and an apology — pardon the phrasing — waves them away. Soon afterward Max overcomes his funk by taking the kite from Dirk and flying it himself…a physical engagement and act of control that immediately causes him to begin brainstorming a new endeavor: The Kite Flying Society, with a flood of names for potential members following close behind. It’s Max regaining control…however far removed from what he might have lost on his way down.

This unstoppable yearning for absolute control is endemic to Anderson as well, and the meticulous structuring of each of his films — starting, of course, with Rushmore — makes that clear. Like Max, there’s not a set detail that escapes his notice, or that could possibly receive too much of his consideration and attention. Like Max, he demands limitless artistic control over his actors, their wardrobes, and the soundtracks playing behind them. And, like Max, his critics would argue that in this search for clinical perfection, he misses the human element that makes these pieces of art worth creating.

This unstoppable yearning for absolute control is endemic to Anderson as well, and the meticulous structuring of each of his films — starting, of course, with Rushmore — makes that clear. Like Max, there’s not a set detail that escapes his notice, or that could possibly receive too much of his consideration and attention. Like Max, he demands limitless artistic control over his actors, their wardrobes, and the soundtracks playing behind them. And, like Max, his critics would argue that in this search for clinical perfection, he misses the human element that makes these pieces of art worth creating.

The latter is a viewpoint I don’t particularly endorse, but it does mean that Anderson’s taking a sideways approach to humanity, which to some is one of his clearest hallmarks and to others is one of his most distracting tendencies. For Max, it was more a question of realizing that those around him — along with the world as it actually is, as opposed to how he wishes it to be — are beautiful in their own way, and worthy of his respect and appreciation for who they are. Max wants to see the world as a series of purposefully constructed moments marching toward a grand statement or triumph…which, it must be said, is exactly the environment Wes Anderson creates for him within the film. But, along the way, those moments reveal weakness, and a genuinely pained emotional core.

It’s not until the end of the film that Max can accept that, sometimes, we just need to take the world for what it is, and realize that while we can’t have everything we think we want, we can live a perfectly fulfilled life with what we have. His father may only be a barber, but that’s a disappointment only in the relative sense that he’s not a neurosurgeon…a fiction Max invented for the sole purpose of being taken more seriously, but which instead proves to be a painfully distinct schism between his fantasy and the real world around him.

It’s not until the end of the film that Max can accept that, sometimes, we just need to take the world for what it is, and realize that while we can’t have everything we think we want, we can live a perfectly fulfilled life with what we have. His father may only be a barber, but that’s a disappointment only in the relative sense that he’s not a neurosurgeon…a fiction Max invented for the sole purpose of being taken more seriously, but which instead proves to be a painfully distinct schism between his fantasy and the real world around him.

And Margaret Yang, a classmate whom he remakes into something more attractive by removing her glasses, doing her hair and dolling her up with makeup, fails to capture his fancy even after all of his meddling. When he dances with her at the end of the film and is sweetly embarrassed by the possibility that she might now be his girlfriend, it’s the real Margret that he finally embraced…not the deliberately manufactured fiction that he put on display in front of everybody. (It’s also worth noting that the character of Margaret Yang was originally intended to have a missing finger — a concept that was latter reappropriated for use in The Royal Tenenbaums but would have even further advanced this film’s manual infatuation.)

Max Fischer’s world is less a place to live than it is a stage upon which he intends to will to life a carefully shaped destiny. He cultivates the world like a gardener, pruning what doesn’t work, attending to what does, and if there’s anything missing that he really wants, he’ll go out there and plant it himself. It’s precisely the opposite of Herman Blume’s worldview, which is more akin to being trapped in a Hell of careless accumulation. He ends up married to a woman he doesn’t love, with two brutish sons he never expected to have, and he’s envious of a 15-year old boy…not because he has everything together — he’s already heard from Dr. Guggenheim what a lousy student Max is — but because he seems to have everything together.

Max’s confidence is seductive. It doesn’t matter to Mr. Blume what Max’s situation actually is — from bad grades to being a simple barber’s son — it matters to him that Max has found a way to thrive within those circumstances, something Blume’s not been able to do. Of course, Max’s very act of thriving is confined to a rather thin and obvious bubble, but it’s more than Blume has, and it’s understandable that he would be seduced by that, just as fans of Wes Anderson’s are seduced by his own, just as clearly manufactured, bubble. It’s a worldview that certain people — Blume and ourselves — active want to buy into.

Max’s confidence is seductive. It doesn’t matter to Mr. Blume what Max’s situation actually is — from bad grades to being a simple barber’s son — it matters to him that Max has found a way to thrive within those circumstances, something Blume’s not been able to do. Of course, Max’s very act of thriving is confined to a rather thin and obvious bubble, but it’s more than Blume has, and it’s understandable that he would be seduced by that, just as fans of Wes Anderson’s are seduced by his own, just as clearly manufactured, bubble. It’s a worldview that certain people — Blume and ourselves — active want to buy into.

As much as Max attempts to restructure the world around him through sheer force of will, Blume — far too late — now attempts the same thing with Max. After all, Ronnie and Donnie are the two sons he never thought he’d have. The unspoken sentiment here is that Max is the son he thought he’d have: an achiever, a charmer, and — seemingly — a self-assured young gentleman. That Max would probably also have preferred being born to this steel mogul is also unspoken, but equally clear, and the fact that they both settle upon Miss Cross in a romantic way that skews enormously toward the motherly on both sides is also quite telling. These are people attempting to build their worlds…Blume for the first time, and Max continually so.

They may be at different stages in their lives, but they yearn for the same things. Blume and Max may seem perfectly suited as father and son surrogates, but as Miss Cross — and many other aspects of the film, including the escalating prank war that nearly results in death — reminds us, they’re made for each other. They’re friends, whether they like it or not, and whether they know it or not. The love story would involve Miss Cross if Max had anything to say about it — his frustration here stems from the fact that, no, for once he doesn’t have anything to say about it — but, in reality, it’s Blume that’s his soul mate.

They may be at different stages in their lives, but they yearn for the same things. Blume and Max may seem perfectly suited as father and son surrogates, but as Miss Cross — and many other aspects of the film, including the escalating prank war that nearly results in death — reminds us, they’re made for each other. They’re friends, whether they like it or not, and whether they know it or not. The love story would involve Miss Cross if Max had anything to say about it — his frustration here stems from the fact that, no, for once he doesn’t have anything to say about it — but, in reality, it’s Blume that’s his soul mate.

It’s a sweet movie with a clear and loving craftsmanship that keeps the tragedy from being too tragic and the comedy from removing it too far from reality. It takes place within a distinct bubble — presented literally as a play — but that’s as it should be. Rushmore is Max’s story, and Max’s story deserves to be told with as much charm and detail and structural obsession as possible.

It’s also Anderson’s story, and an exploration of the results of unchecked control. It makes for a beautiful portrait, but one that needs to be penetrated before you can see the actual human shape that’s being painted.