A (relatively) short and quiet entry this time around, as our segment here picks up exactly where the last one left off. Jane Winslett-Richardson has been shown to her room, Klaus has been meaninglessly cautioned against trying to sleep with her, and Steve entrusts tonight’s footage of the rubber tide to Vikram, who knows from past experience that he is to “print everything.”

From there, our male Zissous split and pair off: old-hand Steve with his wife, and newcomer Ned with even-newer-comer Jane.

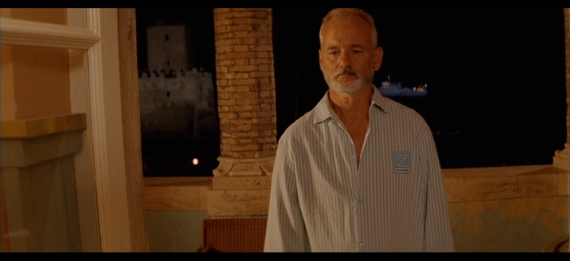

First we follow Steve and Eleanor through a conversation that only lasts about a minute, but manages to be both tense and desperate at the same time. In a gorgeous piece of blocking — though it’s easy to miss this in favor of listening to what’s being said — the two of them stare off at the docked Belafonte, which is lit beautifully…but ultimately needlessly. None of Team Zissou is aboard the ship, and there are no plans for it to go anywhere. It is illuminated for the sake of being illuminated, and even we in the audience can’t appreciate it very much, as the camera doesn’t bring us anywhere near the boat. It is, instead, a tantalizing glimpse of brilliance — double meaning, there — from which we are kept at bay — there, too.

It reminds me of the scene in The Royal Tenenbaums in which Pagoda informs Royal that Etheline intends to remarry. The blocking in that scene positions Pagoda directly in front of the Statue of Liberty, so that it cannot be seen in the final film at all. There’s an anecdote about filming that scene, which I only remember vaguely, as Anderson was questioned about why he’d bother to film his scene there if he wasn’t going to let the audience see the Statue of Liberty. It’s a valid question, but the answer is obvious to me…just as obvious as the Statue of Liberty was in that scene, without it ever being on camera: it’s an act of directorial negative space. Its absence is what gives it presence.

I’m sure that just about anyone watching that scene would recognize that the Statue of Liberty is supposed to be there. We’ve seen enough films and television shows shot in exactly that place that our minds fill in the missing detail. It’s never on film in The Royal Tenenbaums, and yet there it is.

Here that negative space keeps us distanced from the Belafonte. It’s there, and we can see it, but it’s kept deliberately away from us. Lit up gloriously, another aquatic beacon like Lady Liberty, but beyond our grasp. Our minds must fill in the detail.

Personally I like to think that there was another short circuit on the ship, which turned all the lights out, and failing to fix it everyone just returned to the island to worry about it in the morning. Some time after that, the power snapped back on, and nobody’s on board to see it, or shut it off for the night. But that’s just me.

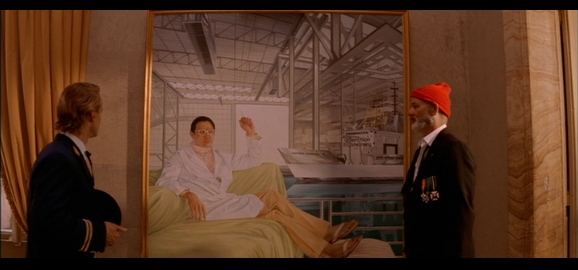

The above image also mirrors that of Steve gazing out toward his wife — and beyond her his ship — from earlier in the film, after his embarrassment at Loquasto.

…which makes it all the more resonant when Eleanor leaves him, alone by the window with his ship in the distance. A reversal of the Loquasto scene, in which it was Eleanor who was alone.

She leaves him here — though not for good, that’s still to come — because she finds out that Steve invited Ned to join them on their mission of revenge. I won’t go into it again, because I think I’ve brought it up at least twice, but, again, this casts some confusion on the earlier scene in which Steve and Eleanor discussed Ned’s joining them. What did she mean then? Why was she receptive to it at that time, but not now?

Once again Steve lapses into aquatic cliche when defending his position, tossing off two watery metaphors meant to explain his reasoning. “We’re going to put him on the map.” And “We’re going to throw him a life preserver.” This latter statement is particularly loaded in light of Ned’s eventual demise…and it’s just one node in an entire web of dark foreshadowing, forecasting the young man’s fate.

Eleanor doesn’t engage with this line of reasoning, as she’s certainly been through it before, but she does ask a question that manages to be both fair and loaded at once: when Steve says he believes in Ned, Eleanor asks him, simply, “Why?”

Steve’s answer provides a complete summary of his entire character. It’s self-centered, hopeful, nostalgic, desperate, and hurt. He says, “Because he looks up to me.”

Steve is nothing without adoration. That’s both despicable and heart-breaking. And we’ll leave the good captain here to ponder that dichotomy.

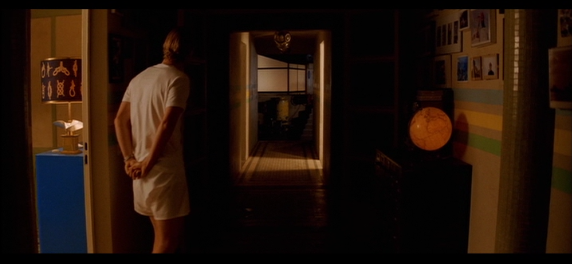

We cut from one Zissou male standing rigid in his company pajamas to the other, standing rigid in his company pajamas. As Steve is feeling abandoned and worthless, Ned is instead optimistic and full of hope. Steve is standing rigid because he’s been wounded — by his own words, tellingly — and Ned is standing rigid because…that’s who he is. With nobody else in the corridor, he still retains proper posture. It’s simply how he was raised…Ned isn’t polite because he wants to be seen as a polite man…he is polite because he is polite. He’s internalized this type of behavior not because he wishes to have good manners, but because this is who he is. And Owen Wilson sells it. Try to find an instance in The Life Aquatic of Wilson slouching or behaving in any kind of physically unbecoming way. I’ll wait. It’s an air-tight performance from an actor who’s far, far from known for any such thing.

Ned is coordinating time off with his employer, Air Kentucky. In fact, before phoning his superior he’s spoken with his colleagues, and worked with them to reorganize the schedule so that the airline will have adequate staffing and complete coverage. That’s just the kind of guy Ned is…he won’t even take personal time without being sure everything will run smoothly for everybody else in his absence.

His boss asks him, though we can’t hear it, something about the voyage he’s about to take. It’s fitting that we don’t hear the question, because Ned’s not quite sure how to answer it. Just like his father before him, his honesty betrays more about his situation than he meant to express: “Well, I just feel I need to see this thing through, sir.”

Ned doesn’t know what’s coming.

He can’t know.

But whatever it is…he needs it.

He believes that this trip, this act of animal revenge, aboard a decaying ship with a financially-troubled captain who is also the father he just met, is something he needs to see through.

Had Ned not been able to arrange coverage with his colleagues, he’d still be alive today.

Had Ned thought twice about any aspect of this trip, or not chosen to finance it himself when Team Zissou went broke, he’d still be alive today.

And the moment he says it, a light is flicked off behind him in the hallway. Another omen unseen.

Ned sacrificed himself…but not for a cause. He sacrificed himself because he needed to know. Whatever it was to know.

And whatever it was he did learn, he took it with him to the bottom of the sea.

It’s a quiet, lost moment in a loud and adventurous film…and it’s one that sticks with me the most.

One thing I’m not sure I ever noticed before this is that it’s raining in the background. There’s a gentle, soothing, watery tapping just on the edge of the soundtrack, and it sets a fantastic mood.

Of course what Ned hears, just after retiring to his own room, is the sound of classical music and Jane’s voice. He follows it down the hallway, and as he does so does the camera, which gives us a glimpse of a pitch-perfect Zissou Compound detail: the sailor’s knots lampshade in Ned’s room.

Another thing I’ve never noticed before. God I love this film.

He finds Jane reading to her unborn British child from Swann’s Way, the first volume of either In Search of Lost Time or Remembrance of Things Past depending upon the translation. Either title would have clear resonance for the eternally backward-facing Steve, though both go unspoken throughout the film. It’s a detail for those who recognize the book (or its text) to pick up on and appreciate for themselves. Like nearly everything else in this film, Anderson refuses to spell it out. To borrow Ned’s phrase, that leaves us pretty strongly adrift in these strange surroundings — just as Ned and Jane are, which I’m sure is deliberate — and it’s up to us to “catch as catch can.”

It’s worth talking about what’s commonly perceived here as a continuity error in the film. Ned asks if Jane is reading poetry, and she replies, “No, it’s a six volume novel,” while gesturing at the pile of books beside her. However there are six books on the chair, and the one she’s reading from would make seven.

However while I know Anderson isn’t exempt from human error, I know even more that he, of all people, isn’t likely to be careless when it comes to details of set design. So it’s either a mis-spoken line that wasn’t caught in the edit (In Search of Lost Time is actually a seven volume novel), a mistake on the part of the character (though I don’t think there’s any reason to assume that based on anything else Jane says or does in the film), or simply a marriage on our part of two disparate facts (Jane’s edition of In Search of Lost Time does indeed come in six volumes, which is actually the case when two of the shorter volumes are bound together, and the pile of books next to her are just books…not necessarily the ones to which she is referring). Whatever it is I won’t say that it’s important, but it does seem to distract some other folks that I’ve seen write about the film, so there you go.

Jane is reading the book aloud and playing classical music for her unborn child’s benefit…the same reason she’s giving up cursing and smoking. Unsurprisingly, the conversation turns quickly to the question of whether or not Steve is Ned’s father, but her questioning hits Ned hard, as his answers are tied up in his mother’s recent sickness and suicide. Jane, perceiving this, backs off.

As much similarity as we’ve seen, and will see, between Ned and Steve, this is one often overlooked similarity between Jane and Steve: both of them seek to structure the world in formats with which they are comfortable. For Steve it’s heavily-edited documentary, and for Jane it’s one-on-one interviewing, in which questions are rattled off and answers returned in easily-publishable capsules. In both cases, Ned doesn’t quite fit their expected molds…though Jane, unlike Steve, has the good grace to back off — which then, interestingly, leaves her as the one outside of her element.

A final great — and easily missable — joke here is how quickly Jane has trashed her cabin. She literally just arrived, but bags are half unpacked, laundry is everywhere, and popcorn is scattered all over the bed. It’s an interesting character touch, and lest you think that she was just too tired to get organized on her first night in the compound, a later scene reveals that she’s done the same to her cabin aboard the Belafonte, where she’s been a resident for a much longer period.

It’s a great, minor, charming quirk for a character who seeks very hard to present herself in a particular way. Open the door and peer inside, and you end up seeing something quite different from what she’d like to project.

Perhaps Steve has an illegitimate daughter, too.

Ned asks if he can listen to Jane read, and she offers to catch him up on the story. Ned, still hopeful, says that he’s sure he’ll be able to figure it out.

Once again, Ned has no idea what he’s getting himself into.

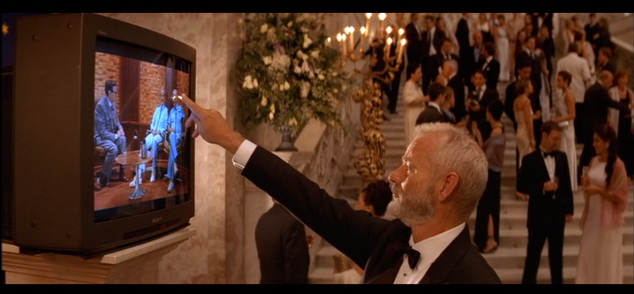

Next: It’s the Steve Zissou show.