Welcome back to Trilogy of Terror, a series in which I take an in-depth look at three related horror films in the run-up to Halloween. They could be films in the same series, films by the same director, films with a common theme, or films with any relationship, really.

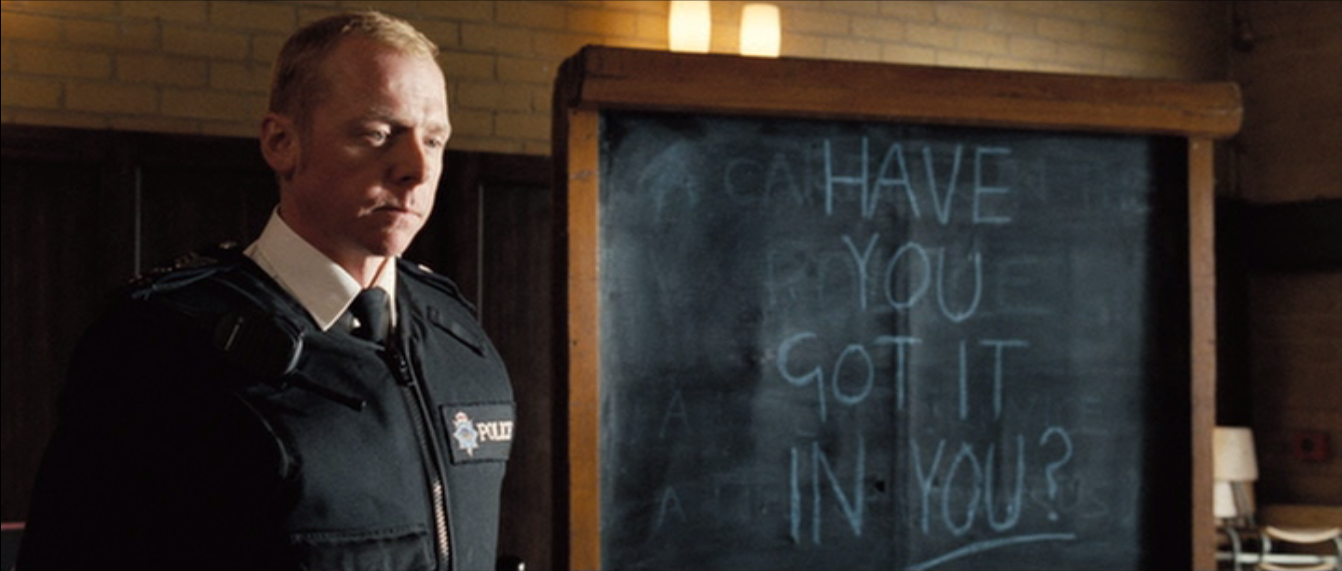

Last year we had some fun with the Blood and Ice Cream Trilogy by Simon Pegg and Edgar Wright. This year we’re much closer to true horror, but that doesn’t mean we won’t be hopping genres.

Alien is an interesting franchise, with each of the main films having a different director, creative vision, and set of themes that it wishes to explore. This has the unfortunate side effect of making the series feel a bit unfocused. In fact, I don’t think it’s easy for somebody to claim to be a fan of the series as a whole.

While I’ve heard people say they like the Back to the Future movies, or the Harry Potter movies, there tends to be more selectiveness when it comes to the Alien films. Many people only like the first two. Many only like the first, or only the second. Somebody, somewhere, must only like the third. (I’m kidding, of course.)

In short, I don’t think there are many fans of the series so much as each individual film has its following. The films may link together to create a longer story, or a vaster understanding of the universe in which they take place, but viewers are welcome to cherrypick. In fact, they’re almost encouraged to do so by the fact that each film is so different from the others.

You may love Alien, and hate Aliens. I think that they’re both good films, but it’s also clear that they take vastly different approaches to the material, and have unique ideas about how their stories should be told. The experience of watching one is entirely different from watching the other.

Whatever you liked or disliked about one Alien film — the atmosphere, the action, the cast — may never come into play again, and each one, I’d argue, exists in its own creative bubble.

As such, the Alien series is more like an anthology of related short fiction than it is an ongoing narrative. This is especially apparent when you factor in the prequel movie(s), and the side series in which Alien and Predator stand around slapping each other.

That all comes later, though. Neither Alien — as the first entry in the series — nor its audience could have possibly been interested in “what came before.” As such, the film establishes everything that it chooses to establish, glosses over what it chooses not to, and weaves its own complete narrative, uncompromised by audience expectation.

It’s also one of the best horror films ever made.

Is it horror, though? Or is it sci-fi?

Well, it’s both, obviously. And not always at the same time. It’s sometimes horror, sometimes sci-fi, and sometimes sci-fi horror. It’s a slasher movie set in space, which allows director Ridley Scott to focus alternately on the slasher and the space as he sees fit.

The rest of the movies would follow a similar template, swapping out “slasher” for another genre. Aliens is a war movie set in space. Alien 3 is a prison movie set in space. Alien: Resurrection is a not-very-good movie set in space.

It’s actually during the long (brilliantly long) stretches of sci-fi that I think Alien is at its best. It’s impressive how well-built Scott’s world is here, when all he strictly needs to do is set up some toys for the alien to eventually kick over.

We get a lot of great, very well-handled moments and fragments of dialogue that open brief windows into the larger universe, and spend very little time explaining them overtly.

What we learn about the ship, the crew members, the company for which they work, even the alien itself, comes incidentally.

It’s second-hand. It’s what the film lets slip between “important” moments, and that’s what makes Alien so effective, so intelligent, so great. It gives the audience credit at every step, not flooding viewers with detail and backstory, but providing it for those who choose to pay attention.

Remember here, too, that Alien was released before the home video renaissance; if you were rewarding those who would watch your movie several times, it was under the assumption that they’d pay to see it several times in theaters. Scott banked on a repeat audience that would have the patience for a layered narrative, and, somewhat shockingly, he succeeded.

The film opens with the crew of the Nostromo being revived from deep sleep. They’re on their way back to Earth — from parts and activities unknown — but that’s not why the ship’s computer wakes them up; it’s picked up what seems to be a distress beacon.

The first stretch of the movie is masterfully sedate. One by one the characters rise from their sleep pods…yawn…get slowly about the day-to-day. They make breakfast. They perform basic readings to figure out where they are. They complain about their pay.

We learn everything we need to know about how the team members interact — and either work together or fail to work together — here, while nothing is happening, while things are quiet. The movie wakes up along with them, just as slowly. It’s not in any more of a rush than the characters are.

We learn, of course, a few things more clearly than we learn others. Mainly we learn that there’s some friction between the engineering team and the main crew. The former is comprised of two people, Parker and Brett, and at some point before they entered deep sleep, they voiced their misgivings about the pay structure. The discussion was obviously tabled — or at least not resolved to their satisfaction — and it comes up again now. Parker pushes the issue, Brett quietly lets the discussion unfold around him.

Their relationship, and their relationship as a pair to the rest of the crew, comes through clearly. Whatever they do or don’t actually deserve, it’s clear what they’re getting, and that’s that. We have a career’s worth of frustration raised and dismissed in just a minute of screentime…which is certainly why there is so much frustration.

We also get a good sense of how distant Ash, the science officer, is from the rest of the crew. It’s easy (by design) to read this as a kind of emotional detachment, or intellectual aloofness.

He doesn’t joke around. He isn’t playful. He doesn’t even seem to be especially interested in anything his crewmates care about. These are qualities that could well make him a great science officer — one who adheres to logic and reason over worries and gut feelings — but we learn later that he only recently joined the crew. Ash’s detachment is felt here, and explained more and more deeply as the film unfolds, but the mere fact that he’s the new guy means that he won’t fit as well, and the crew may be as detached from him as he is from them.

We’re also introduced to Ellen Ripley, of course, played incredibly by Sigourney Weaver. And it’s here that the length of the franchise robs us of a great surprise. By now, whether you’ve seen any of the films or not, you know that Weaver is a constant. She’s the main recurring character, outside of the general “alien” itself. We’ve seen her in trailers, on movie posters, on DVD boxes for years. So watching the original Alien as a newcomer, it’s impossible not to know that she’s the protagonist.

This is all understandable, but disappointing, as Alien takes great pains not to single Weaver out from the start.

It’s an ensemble cast. No one character is present for all of the important conversations, no one character makes the decisions that save or damn them, and no one character really calls the shots. Audiences experiencing Alien for the first time in 1979 may well have been under the impression that Captain Dallas (Tom Skerritt) was the main character. After all, he’s handsome. He’s rugged. He holds the highest rank.

He’s…y’know. Male.

Alien gradually, artfully narrows its perspective until it belongs to Ripley. I’m speaking literally here, too, as she narrates the dénouement in the first person. Which is a telling change from the soundless establishing text that opens the film. Alien isn’t Ripley’s story; it becomes Ripley’s story.

In doing so, it also reveals itself as a woman’s story. It may or may not serve as a deliberate comment on passive sexism in real, actual workplaces, but it certainly comments on it within the universe of the film.

Throughout Alien, Ripley is interrupted. Spoken over. Ignored. Contradicted. Even when she’s left officially in charge of the Nostromo, her authority is overridden.

She’s questioned more sharply and more frequently than the other characters are. She’s discouraged from speaking up at all. When she asks questions she has to do so several times, and her male crewmates respond through gritted teeth or with rolling eyes.

Why? Because Ripley isn’t playing by their rules.

The safety of the crew is important to her. She respects protocol. She understands enough of what’s happening to find holes in the official explanation…or at least to smell bullshit. But she’s a woman, and she’s not behaving the way a woman should, so they need to put her in her place.

Okay, yes, she’s acting in the best interest of the crew and voicing valid concerns that would prevent the entire situation from spiraling out of control the way it ultimately does, but, man, she sure needs to learn to speak when spoken to.

The crew’s treatment of Ripley is further emphasized by the much more positive way they treat the other female aboard: Lambert.

Lambert is a more traditional woman. She doesn’t push. She doesn’t fight. She might mutter under her breath now and again, but she knows better than to talk back.

In one very telling scene she tries to relay what she thinks is critical information to Dallas…and he interrupts her, telling her to give him the short version.

And you know what? She does.

Lambert does as she’s told.

Would Ripley have responded the same way? Of course not. Because Ripley, foolish girl, would have actually thought that what she had to say was important.

So Lambert gets the better treatment. She plays the game. When Dallas assigns squads to comb the ship for the alien stowaway, she gets to be on the A-team. Ripley, in an unspoken but clear fuck-you, gets saddled with the two disgruntled maintenance guys.

Of course, we all know how the film ends by now. Ultimately Ripley’s concern — along with her pragmatism, her understanding, her willingness to lose a lot in order to save a little — is vindicated. She goes from being dismissed and talked over and contradicted to quite literally having the last word. The woman gets to talk…after absolutely everybody else is silenced forever.

You know, watching Alien during this particular election cycle sure brings a lot of things into sharp focus…

Oh, but, wait, okay, so, you may not believe me here, but: there’s an alien in this movie! Sorry. Sorta just skipped right past all that.

Yes, the beacon leads the crew of the Nostromo to another ship, marooned on a hostile planet. It’s devoid of life…at least as far as they can tell initially. Further investigation leads them to a misty area below-deck, full of eggs. One of the crewmen gets a bit too curious, and ends up with a strange creature attached to his face.

And this is where the film veers directly into horror, but, unfortunately, it’s also the most effective horror in the film. In terms of scares, Alien peaks a bit early, with the facehugger being a genuinely frightening — and horrifically believable — movie monster.

It’s also something that every one of this film’s sequels has failed to top.

The facehugger is scary. So much so that I’ve actually had nightmares about it, and that usually won’t happen for some imaginary beastie I’ve seen in a film.

This thing, though?

Holy hell this thing.

On the whole, the alien itself — the final, physical presence — is the area in which the film has noticeably aged. The film’s overall visuals and effects have held up brilliantly, but the ultimate alien is a bit too obviously a guy in a rubber suit. Terrifying for 1979, probably pretty scary through the 80s, and now…bordering on silly.

The design of the creature is without question fantastic, but the actual execution feels at times like the crew is playing an especially tense game of hide and seek with a guy in a very expensive Halloween costume.

Not so with the facehugger. That thing looks — to this day — like an actual, living monster.

It’s terrifying. I get chills just hearing Ash refer to its “knuckle.” Its design — and execution — is amazing, and feels horribly timeless, as though this pale, fleshy succubus will be causing feelings of unease in audiences long after you and I are dead and gone.

It looks real. It breathes, for Christ’s sake. And while I know — of course — that the thing exists only within the confines of the film’s reality, I’m unable to see it as “just” a plastic prop.

It feels alive, and watching it tighten its tail around Kane’s neck when they first attempt to remove it is just…scary.

The facehugger benefits from the same vagueness of detail as the rest of the film. We hear a bit about it, courtesy of Ash’s findings, but are left to imagine the most horrible parts. The tube forced down a human neck to feed it oxygen. The eggs laid in the chest. The disorientation involved that leaves the victim to remember nothing more than awful dreams of suffocation…

We see the facehugger do enough. But we hear about more, and that’s what keeps it scary. It’s still mysterious, no matter how clearly we see it on the screen. Often in horror films (this one included) the best course of action is to show the monster as fleetingly and infrequently as possible. This allows the viewer’s imagination to take over, as what they will see with their mind’s eye will likely be much scarier than anything you can achieve with makeup and prosthetics.

But the facehugger isn’t fleeting.

It’s there.

It’s…doing whatever it’s doing.

It’s in plain sight. The crew members stare at it. They try to remove it. They analyze it. They eventually find its corpse and prod at it.

And it never — ever — gets any less scary for it, because no matter how much time we spend with it, our imaginations still have a lot to work with. We’re still inventing our own horrors. And the more realistic that little prop looks — whether it’s the pulsing silhouette in the egg or the slimy innards its death allows us to probe — the more we are able to believe in the horrors we don’t see.

The film letting us spend so much time with the facehugger is a mark of bravery, and confidence. “Go ahead,” it says. “Look. You still won’t see the scariest part.”

And of course it all leads to one of the most famous scenes in science-fiction history. By now so many other productions have borrowed it and homaged it and parodied it that it’s been robbed of its necessary surprise, and it’s one of those film moments I really wish I could travel back in time to witness firsthand, with an audience that had no idea what was coming, and couldn’t possibly have known how to react.

Once the chestburster is — ahem — out of the film’s system, we’re squarely in slasher territory. The characters are stuck, they’re up against a killer with inhuman strength, and at least a few of them are going to have to die before they figure out how to defeat it. And, spoiler: damn…there really is no defeating it.

One of Alien‘s great narrative flourishes is the way it doesn’t allow the crew to kill it. While trying to cut the facehugger off of Kane, they discover that the alien has acid for blood. And a tiny little squirt — about the same that you’d get from nicking your finger in the kitchen — burns through several levels of the ship.

It’s a detail that makes the alien scarier — and, er…alien — and it also solves the basic logistical question of why they don’t just fight like hell against it: even if they did manage to kill it, its blood would eat through the hull and take them all with it.

It’s a deeply efficient detail that answers a lot of questions and does an impressive amount of storytelling all on its own.

The tragedy of the Nostromo unfolds as it must. After all, once you let a ruthless killer on board and establish that you can’t shoot it, stab it, or blow it up, there’s really no chance of a happy ending.

Prior to that, of course, there were several chances of a happy ending.

Respecting quarantine procedure, for instance.

Or deciphering the beacon before sending out the search party.

Or…y’know what? Let’s just say “letting Ripley finish her sentences” and be done with it.

Ripley is — and I genuinely can’t fathom anybody disagreeing with this — the film’s crowning achievement. With no biographical details to speak of (outside of approximate age and the fact that she’s a pet owner), she feels fully drawn. She feels real. Too real, so that the crew’s steadfast refusal to take her seriously registers as its own kind of horror…the horror of a life sidelined in favor of somebody else’s interests.

Ripley’s experience is relateable. It’s understandable. It’s frustrating. And it makes her eventual survival that much more satisfying. Not because she was strong enough to overpower the alien; she wasn’t. She was just the most level-headed of her crew, was able to think more clearly, and was able to change her plans and then change them again as various solutions to the problem closed themselves off.

She wasn’t a singular, blessed bad-ass. She was just the most competent person on the ship. That’s all. She was an everywoman. Not transformed by a threat into an ass-kicking hero, but emboldened by danger to take her own ideas more seriously. And as the objections — and those making the objections — fell away one by one, she became more empowered to place them into action.

This is something that the sequels, I feel, really missed. Ellen Ripley becomes a sort of Chosen One, at the ultimate expense of her humanity. She becomes almost hyper-competent, whereas her role in the first film is defined by relative competence.

Ripley shouldn’t survive because she’s an invincible, fearless powerhouse; she should survive because the others don’t. It’s difficult to identify with an adept alien whisperer, but pretty easy to identify with somebody just resourceful enough to make it out alive.

Alien is a nearly perfect movie. In fact, the only thing I keep going back and forth on is the reveal that Ash is an android, sent by the company to ensure that the crew does its bidding. Granted, both aspects of this (the company’s intentions and Ripley’s rightful distrust of androids) are elaborated upon to great effect in the sequel, but for now it just feels a little muddy.

I don’t dislike it, exactly, but I’m not sure that the film needs another active villain on the ship. There’s already a murderer, and I think that I’d slightly prefer the crew to unknowingly endanger each other through poor judgment and thickheadedness than to have one member of the crew programmed to endanger them.

It also provides Ash with another specific reason to dismiss Ripley’s concerns, which I don’t think he needs.

The others dismiss her, and they’re not androids. They do it because they’re people. Tired people who don’t want to be bothered. People with egos they don’t like to see pierced. People in a panic making decisions they can never take back.

“I’m a robot so, yeah…” is a much less compelling explanation than the one that arises from basic human behavior and gender conflict, and I definitely don’t think we need a sci-fi explanation for someone being a dick.

I’m not saying it was a bad creative decision, necessarily, but it’s the one I do second guess from time to time.

But it’s Alien, and if its biggest misstep is something I can still enjoy, understand, and appreciate, then I’m really not surprised at all that it quickly became — and remains — such an important film. A film that instantly cemented its place in horror history, sci-fi history, and film history, and continues to shape our expectations of similar films today.

It’s a truly great movie, front to back. One that has absolutely earned its reputation. One you feel familiar with even if you haven’t seen it. And when you do finally sit down to watch it, you’ll likely see that it’s still better than anyone led you to believe. It’s one of my favorites, and, in my opinion, one of the best.

The tragedy of the Nostromo is one we already know. Corporate indifference, class conflict, inequality. Rules for the sake of rules. Safety compromised by shortcuts. Bad decisions made in heat. People who don’t necessarily get along having to work together, because a job’s a job. Being damned in an instant by the interests of another.

Sure, the alien didn’t make things better.

But was life all that great to begin with?

Tune in next week, when we’ll discuss Aliens.