I don’t normally do “games of the year” lists, and that’s primarily because I’m only rarely playing games released in the current year. I’ll have one or two I look forward to, and I may or may not get around to them in a timely fashion. I’m usually working through a backlog, or revisiting old games that I already know I love. But this year, for whatever reason, I played a lot of games without being especially far removed from their release. And, what’s more, most of what I played was really good, and worth spotlighting.

In every case with the games you’ll see below, I wanted to sit down and write long, dedicated posts about them. In every case, I didn’t do that. (I’m nothing if not consistent.) So this is a good excuse to run down more quickly and succinctly what I loved about these games, and raise the main points I intended to raise in longer essays. Also, lists always get pretty good views and tend to engender discussion (and suggestions) so I hope you all enjoy disagreeing with me.

Oh, and because it’s my site and I MAKE THE RULES, I’m allowing myself to take games from 2016 into consideration. Why? Because I sure as heck didn’t do a list like this last year, and if I played them for the first time in 2017, I’m counting them. That’s why this is a top 10 of my 2017. If you don’t like it, take over my life and lead it differently. Really; I won’t stop you!

10) I Am Setsuna

Thanks to a really nice deal on Amazon, I was able to get Final Fantasy XV shortly after it launched for about half price. I was very excited, because I thought I’d have to wait a year or so before the cost came down enough for me to buy it. The reluctance to shell out full price, though, wasn’t really a question of money; it was a psychological barrier that I kept in place because I knew — knew — that if I started playing Final Fantasy XV, it would suck so much of my life away that I’d never get back.

But it was cheap. I’d be stupid not to buy it at 50-ish percent off. So I bought it. And I started playing it…and far from sucking my life away, it was a chore to ever boot up.

I didn’t like it. It wasn’t fun. All of the ingredients were there, and I didn’t feel tricked by the marketing campaign or anything. Whatever I expected to find, I found. It just…wasn’t fulfilling. Just like I expected, I was cruising around a big world in a cool car with my cool friends, pulling over to fight monsters. We’d meet eccentric characters, admire gorgeous landscapes, and let the plot unfold at (largely) our own pace.

But it wasn’t fun. I didn’t care. I tried to care. I played it for many hours after I realized I didn’t care, hoping I eventually would. But I didn’t. And so I booted up something else published by Square Enix. Something I also got on sale, which just kind of sat around. Something less ostentatious than Final Fantasy XV. Something easy to overlook. Something bracingly simple and unassuming. And I was hooked from the get-go.

To me, I Am Setsuna really does carve out its identity by contrast. On its own merits, sure, I think it’s a good game. But when stacked up against celebrity titles like Final Fantasy XV, it seems to actively pose the question, “Do you need all of that?”

As games grow larger and more complex, flashier and more advanced, are we actually moving forward? There’s not a definitive answer there. In fact, “not always” is about as close as we can get to a uniform truth. I Am Setsuna is a throwback to the narrative and gameplay simplicity of the SNES era, with graphics that are only marginally more advanced. Yet — or perhaps because of this — it successfully weaves its quiet story of desperation and detachment. It builds a world without hope, populated by characters without hope. Its central plot, after all, sees you serving as bodyguard to a human sacrifice, escorting her to her destination safely…where, of course, she will die.

It’s decidedly minimalist in every sense, right down to the breathtaking, heartbreaking soundtrack that consists almost entirely of a lone piano. I Am Setsuna isn’t overwhelming in its despair…rather it leaves opportunities open for you to find joy along the way, no matter how bleak the journey may be. Maybe you find it in those sparse, twinkling keys. Maybe you find it in the rare moments of levity between two characters. Maybe you find it in another character, who is willing to sacrifice his or her own safety to help you complete your mission.

The snowy wasteland of I Am Setsuna is its simplest and most successful innovation. As long as I live, I’ll never forget leaving trails through the frozen world to the haunting notes of a cold piano. As much as Final Fantasy XV worked to make itself memorable, it’s I Am Setsuna that I won’t forget.

9) Fallout 4: Far Harbor

I debated whether or not to count this as a “game,” but…what the hell. Sure, it’s technically an expansion pack for Fallout 4, but it provides a large, isolated map, unique locations, unique quests, a unique story, unique gear…you may need to own Fallout 4 to play it, but it is a complete and self-contained experience.

Mainly, though, I wanted to call it out for adding something that the base game was sorely missing: genuine ethical conflict. Granted, Far Habor doesn’t entirely scratch my itch in that regard — the most problematic ethical conundrums unfold off camera, before you arrive — but it at least raises difficult questions that are worth thinking through.

The plot kicks off in a way guaranteed to grab my attention: you’re called upon to play detective. As much as I love shooting Super Mutants in the head with a railgun, I like pretending my last name is Marlowe even more. Far Harbor asks you to travel along with out-of-time noir detective Nick Valentine (one of Fallout 4‘s more impressive characters to begin with) in search of a young girl who’s gone missing.

This conveniently takes you to the town of Far Habor, and the larger island around it. From here, in true Fallout fashion, you can do whatever you like. You can immediately seek out the girl, you can get embroiled in any number of sidequests, you can aimlessly wander in search of interesting locations and stories, or you can toy — deliberately or not — with everybody’s fates.

So, hey, it’s more Fallout 4. And while it’s my least favorite of the Bethesda-era games, I’d be lying if I said there wasn’t enough appeal in that alone for me to enjoy it.

But at the center of everything in this expansion — both narratively and geographically — is DiMA, perhaps the richest and most complex character in the entire game. DiMA is a synth…the same model as Nick Valentine. He’s lived on the island since he escaped The Institute, and helped it grow. He assisted the Children of Atom when they arrived, and he’s helped the people of Far Harbor to survive the noxious fog that coats the island. What’s more, he’s successfully brokered a peace between these two mutually antagonistic factions. Oh, and he runs a large and efficient colony for refugee synths.

I plan on avoiding specific spoilers, but if you don’t even want to hear about general revelations in the game, skip to the next entry now.

DiMA is a good guy. He helps people. He keeps everybody safe.

And yet, as you dig into his history, you learn that he didn’t do any of this in ethical ways. If he’s a good guy today, it’s only because he was not one yesterday. As a robot, DiMA has the ability to erase his own memories, and he indeed does so. You are able to piece the deleted data back together, revealing DiMA’s misdeeds, and when DiMA learns of what he’s done, he’s appropriately horrified. He’s such a good person that he doesn’t even seek to justify his actions…he’s appalled by them.

And yet…he’s still the person who committed them.

The ethical question, again, is resolved by the time you arrive. DiMA already acted monstrously in pursuit of a brighter tomorrow. And, well, he succeeded. It’s brighter. Whatever you may think of his methods, they panned out the way he expected them to. The island knows peace. It’s a peace that must be actively and painstakingly maintained, but the residents are safe from each other, in a way that they truly are not in other areas we’ve explored in Fallout games. DiMA raises and answers his own question about the ends justifying the means before we ever meet him.

But once we do, we have an after-the-fact ethical question to face. Should DiMA escape justice?

That one’s entirely up to us. And while I’ve made my decision and completed the storyline of Far Habor, I think I can go back and forth on the right answer all day.

What’s more, that’s just one (admittedly major) aspect of the expansion. Elsewhere there is so much more to enjoy. There’s Jule, the tragic synth forced to live with a botched memory wipe. There’s The Mariner, the rightful owner of Far Habor who labors day and night to keep anyone in need of shelter safe. And there’s Kasumi, the missing girl whose identity crisis kicks the entire story into gear. She flees her home and family because she’s not sure who she is anymore…and no matter what you do in the DLC, neither you nor she will leave with a definite answer. Is she a synth? Is she a human being? The ethics behind the decisions you make will be at least in part determined by what you believe, but you’ll never know if what you believe is true.

In many ways, Far Harbor does Fallout 4 better than Fallout 4. It adds much more than an environment.

8) Inside

One of my favorite games of all time is Limbo. It was striking, surprising, and remarkably effective for such a simple game. (I never believed a game that only saw you walking, jumping, and grabbing could possibly feel so deep and profound.) Inside, a followup by the same team, somehow escaped my attention upon release. But I finally sat down to play it, and found myself impressed and in love all over again.

Not “in love” because my heart was warmed or inspired or…anything positive, really. Rather “in love” with the bravery of a game that unfolds in such oblique, mysterious ways, telling you more with every screen but never enough to truly orient you. Never explaining the who, what, when, why, or where. Never giving you a direct reason for progressing, yet compelling you to progress all the same.

Limbo was a remarkable achievement in that area, I feel. I’ve played through it multiple times and still don’t know what it’s about…beyond the obvious (but fair) observation that it’s about the experience. And it’s a great, unique, memorable experience to be sure.

Inside follows its predecessor’s lead in every way I could have wanted it to. Its simplicity, its mystery, its quality.

The nature of your plight seems to change multiple times over the course of the game. At first it feels like escape. Later, it feels like infiltration. Later still…well, if you played it you know what comes later still, but I won’t spoil it specifically here. This is in contrast to Limbo which, in my opinion, didn’t really define the nature of your plight in any way whatsoever until its ending. Inside is a little trickier, and plays a little bit more actively with your expectations.

One thing I regretted from my initial experience of Limbo was that I didn’t play it all in one sitting. I’d get a bit further, then do something else. I’d come back to it in a few days and make a little more progress. At one point I stopped playing, picked it up again the next day, and saw that I’d taken a break right before the end of the game. That’s part of the problem with not defining a clear goal: players never know how close or far from that goal they are. Had I known what I was chasing, I might have been more aware of the fact that I was nearing it.

And that always bothered me. It wasn’t Limbo‘s fault…I was mainly mad at myself that I put a break between the ramp up and the conclusion. I made sure to rectify that with Inside, which I saved for one long sitting, and I’m glad I did. I allowed the game to dictate its pacing, its rhythm, its flow. And so each segment — isolated though each may feel — worked in service of a greater psychological and emotional whole. What’s more, the running theme of agency was made so much more ipactful because I experienced it in so many ways over the course of such a short time.

Playing this game made me dream of a sort of Twilight Zone series of games. Same engine, same basic controls, but with a different story unfolding in each installment. Maybe we could treat it like an episodic season of games (see the next entry), with a small number of regular releases. Each entry is self-contained, but we’d end up with an anthology of tales like Limbo and Inside. Games that disturb us the way the best episodes of Rod Serling’s series did. Games that explore major themes in artistic, artful ways. Games that mean far more than they say.

I doubt we’ll ever see this kind of game released at a regular clip, and I’m not even convinced it would be a good thing if we did. But I’m glad we at least have this pair of bizarre, disorienting masterpieces to return to again and again.

7) The Walking Dead: A New Frontier

Maybe I’m mistaken, but I seem to recall The Walking Dead: A New Frontier being advertised originally as The Walking Dead: Season Three. It’s not a crucial change, but it’s indicative of how detached this season is from the two that preceded it.

If you haven’t played the previous games, Telltale’s The Walking Dead is a series of episodic games that last around two hours apiece. Each episode picks up where the previous left off, and the decisions you make affect what happens in later games…along with who will or won’t be around for the next leg of the journey.

The gameplay is more about choice than it is about action. You certainly have your moments of popping zombies in the head, but the more important sequences are much different, such as when you need to divvy up the remaining food among survivors, knowing full well there’s not enough to go around. Or when you need to give your young charge Clementine just one piece of advice to carry her along through the unfolding apocalypse. Or when you need to decide whether or not to make a pass at your brother’s lonely wife.

Everything you do or say is likely to have some degree of consequence, which is why it was a bit surprising that A New Frontier followed new characters entirely, in a new setting, with a new goal. It wasn’t so much that your previous decisions didn’t matter…they still had the same emotional impact they ever had. It was more that they suddenly felt irrelevant, part of a parallel universe, as though A New Frontier were a kind of reboot.

And that makes sense to me. It gets increasingly difficult to sell a batch of games with the caveat that you should have played all of the previous batches as well. Starting over with new characters is fair. After all…it’s the end of civilization. There are more stories to tell outside of one small group of survivors.

A New Frontier did have previous protagonist Clementine, and it did actually follow up on a number of plot threads from the previous game, but its focus was firmly on newcomer Javier and his relationship with his estranged brother David. Someone buying this set of games without having played the others may feel a bit lost at times, but those times would be infrequent. Any important information would be information dished out here and now.

And, overall, I think that worked. It makes A New Frontier feel much more like a side story than a sequel, but it tells a compelling and deeply personal story about family, about relationships, about loss, and about identity. After all, Javi is and has always been the family fuckup. For him to be in charge of anybody, himself included, these must be seriously trying times.

Part of me wishes Clementine didn’t show up. As much as I like this latest branch of her story, forcing her into A New Frontier requires a pretty abrupt severing of much of season two’s narrative. In fact, I spent season two forming a very strong bond with someone I thought was an important and fascinating character…only to have her instantly killed off at the start of A New Frontier. It felt like a cold disservice to her more than it was one to me.

But I enjoyed A New Frontier for what it was, and the idea of an isolated season worked in favor of raised stakes. If this was the only time we’d ever see Javi and co., nobody had to survive to keep the story going. The family fuckup could well fuck up the family, and that would be that. Gravity could assert itself. Everybody could be crushed by the plans crumbling down around them. And, indeed, the story can play out a number of different ways.

However it plays out, though, you’re sure to have your patience, your loyalty, and your tolerance tested many times over. And that’s the best trick A New Frontier pulls. It places one of gaming’s most effective family dramas in the heart of a zombie swarm, where nothing’s likely to be resolved positively.

6) Battle Chef Brigade

Sometimes a game has a concept so perfect, I know I’m going to buy it no matter what. Even if the reviews are poor. Even if people tell me it’s junk. Even if it looks terrible. There are just some central conceits that are too perfect to let pass me by. Battle Chef Brigade was one of those for sure…and it also turned out to be pretty great, which is a nice bonus.

The idea is essentially that it’s Iron Chef set in a fantasy realm. So for that overlap between “nerds” and “viewers of Food Network” (a niche I am quite comfortable occupying, thank you very much) you really can’t ask for more. The gameplay involves hunting and killing the creatures that will serve as your ingredients, and then preparing your dish for harsh and particular judges.

Think an episode of Iron Chef in which the theme ingredient is crab meat, and we spend half the show watching Geoffrey Zakarian stalk giant crustacean monsters in a swamp.

That’s the kind of thing that should be fun even if it doesn’t work as well as intended, but Battle Chef Brigade works pretty damned well. The combat felt a little clunky to me at first, but once it clicks, it’s actually quite fluid and interesting. And the cooking sequences seem a bit lame at first — oh, a match-three puzzle game? yay… — but are actually more frantic and involved than you’d expect.

Perhaps my favorite thing about the game, though, is its art style. It’s light on animation, but heavy on character and personality. Everything just looks…lovely. The game establishes and maintains a distinct visual approach that reminds me of storybooks several generations removed from the ones I used to read. Maybe storybooks from an alternate reality, in which the heroine bravely leaves home to seek her fortune in cooking competitions.

And that heroine, I have to say, is one of the main draws of Battle Chef Brigade for me. Mina was just so charming that I wanted to spend time hunting and cooking with her, competition or not. I wanted to roam around town with her. I wanted to talk to strange and wonderful people with her. I wanted her to win, because she worked hard enough and wanted it bad enough that she deserved it.

The game is packed full of little side quests and character interactions that make it feel so warm. With competition at the heart of the game’s progression, only rarely does it feel truly combative. More often you have two skilled culinary artists squaring off with each other through mutual respect. There’s so much camaraderie in this game that it’s almost inspiring. It’s a nice and unexpected reminder that while two individuals may hope for different outcomes, they don’t need to be at each other’s throats.

Battle Chef Brigade is a great game to unwind with. There’s evidently also a daily challenge feature, unrelated to the actual plot of the game, which I haven’t tried yet but really should. It’s a game to visit and catch up with when you need a break from the real world. It’s a game where you might need to beat up a dragon to please a judge, and whatever the outcome, whether you win or lose, you feel good about the effort.

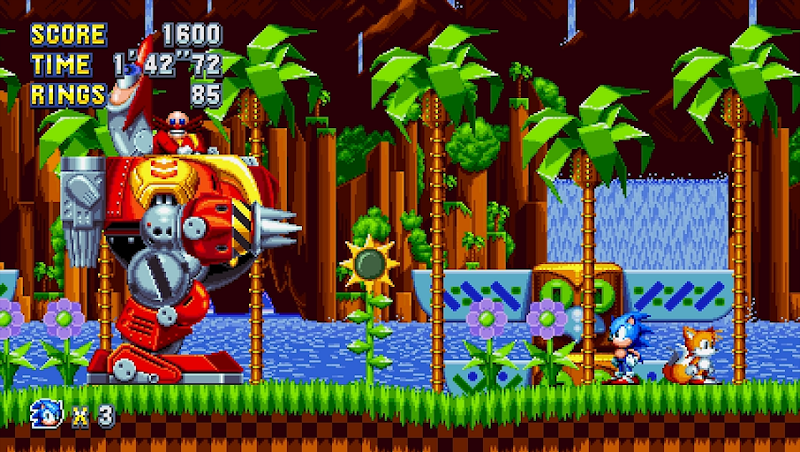

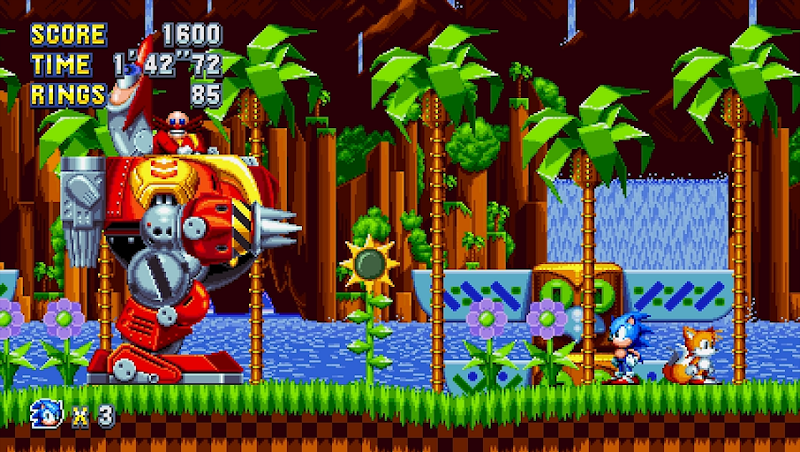

5) Sonic Mania

I grew up in a Nintendo household, which I’m sure couldn’t possibly surprise anyone. But, to be honest, I was never really jealous of those who had Sega consoles. There were fun games and crappy games on both sides, but I couldn’t imagine trading a Nintendo library for a Sega one. It seemed like it would be a huge step downward. So I’d play Sega when a Sega was available, but I’d go home to the comforting arms of Nintendo, where I belonged.

Except when it came to Sonic.

Sonic was…great, actually. My uncle had the first game, and years later one of the kids I babysat had the second and eventually third. I put a lot of hours into all of them — the second game especially, which I still believe is the best one — and felt, for the only times, a feeling of envy.

It still wasn’t enough to make me want a Genesis, but at least I knew if I had a Genesis, I’d have three great games I would not likely tire of.

They were fun. They were colorful. They had stellar soundtracks. There was always another secret or twist to the level design to discover. I’d be lying if I said I was actually much good at the games, but I enjoyed them a huge amount. Later in life, long after Sega stopped making consoles, I played those three games (& Knuckles) properly, and found them to have held up pretty well. They were still great, and I enjoyed playing through somebody else’s childhood.

But that was…it. 3D Sonic games never interested me much, and the ones I did play largely didn’t impress me. (I still hold to my opinion that Sonic Lost World on the WiiU was far better than anyone gave it credit for being, though.) So even though I finally got to become a Sonic fan, I didn’t care enough to seek out any of his new games. In other words, I didn’t finish the 2D games and dive excitedly into his other outings…I finished his 2D games and thought, “Yeah, those were good. That’ll do.”

Sonic Mania, though, made me pay attention. I’m a sucker for retro throwbacks in general, and this one looked like an actual lost title from that era. I was excited to give it a spin…especially when the reviews came in and were uniformly positive. When’s the last time that happened with any Sonic game?

It was everything I could have wanted. Brainless, inventive, giddy fun. It reveled in the series’ history, which I’m sure was a treat for bigger fans than I’ll ever be, but it also tapped into everything that made the original games work and refined anything that didn’t. It did a great job both of recreating what the original games were and what our memories of them were. Playing it put me immediately back in mind of how I felt when I was a kid, experiencing levels for the first time, wondering what could possibly come next.

Sonic Mania is one of the very rare games that I completed and then immediately played through again. In fact, I’ve made multiple trips through the game by this point, and I’ve enjoyed it a little more each time. It isn’t easy to live up to nostalgic expectation, but Sonic Mania outdid itself. Of course, even in 2017, it still comes in behind the plumber.

4) Super Mario Odyssey

Mario’s been quite a fortunate character in the sense that he’s never had any real missteps. He’s had a few games with mixed reception (such as Super Mario Sunshine) and a few outliers that are easy to ignore (such as Mario’s Time Machine), but, on the whole, Mario’s presence in something is a reliable seal of quality. His games are fun, addictive, and positively overflowing with joy.

So it says something that Super Mario Odyssey is clearly one of his best.

As much as this game gets credit for returning to the massive sandbox layouts of Super Mario 64, it also does so much new and does it so well. The most obvious innovation is Cappy, a sentient hat Mario tosses at enemies and NPCs to temporarily possess them. It’s a concept that sounds distractingly gimmicky on paper, but which is integrated so well it’s difficult to imagine Super Mario Odyssey being even half as fun without it.

Each of the worlds features new ways to explore it, new things to find, new challenges to complete, but as with any of the best Mario games, the real attraction is simply being there, hopping around, exploring, admiring the inventiveness of Nintendo at its best.

I knew Super Mario Odyssey was going to be great. I waited for its release to pick up a Switch, and it absolutely lived up to my expectations. While the main storyline itself can be conquered in just a few hours, there are a total of 999 Power Moons to track down throughout the game, giving you a lot of reason to return to it many times over. My own plan is to pop in for a few hours here and there, finding whatever I can find, eventually getting them all…and then starting all over again.

Mario games are built to be replayable, and there’s no way Super Mario Odyssey will turn out to be any different. It’s a game that will lead to breathtaking speedruns. It’s a game that will be worth revisiting just to beat your times in the footraces. It’s a game you’ll think about long after shutting down the Switch, looking forward to when you’ll have time to boot it up again.

One very interesting evolution to me is the inclusion of vocal tracks. The music throughout the game is pretty solid, as is to be expected, but there are a handful of tracks on which there is actual singing, which I’m pretty sure is a first for a Mario game. What’s more…they’re really, really good, especially one that plays toward the very end.

There’s a lot that Super Mario Odyssey does that I didn’t expect it to do, and there hasn’t been a moment yet that’s disappointed me. It’s all just been varying degrees of fun and exciting, and watching Mario march through and pay tribute to so many aspects of his heritage is like taking a trip through my own life, as well. I’ve known Mario since Donkey Kong, and I’ve actively followed his adventures since Super Mario Bros.

I care about the guy. I care about what he gets up to. However old I get, however rough the world gets, Mario’s still smiling, still laughing, still showing us new ways to have fun.

Super Mario Odyssey acknowledges the character’s history in a way that reminds us of his consistency, his reliability, his steadfast refusal to accept defeat. On the rare occasions that he does stumble, he hops right back up, better than ever before.

3) The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild

I could have played Breath of the Wild much sooner than I did…but I didn’t want to. It got great reviews. People said it was the best in the series. My friends assured me I’d love it.

But I remembered Twilight Princess. People said the same thing about that.

And I remembered Skyward Sword. People said the same thing about that.

At some point, after you stop enjoying something, you need to stop going back. Especially when that something costs you $60 a pop.

I love the Zelda series. Nearly all of the games blew me away and became instant favorites. I still feel that A Link to the Past > Ocarina of Time > Majora’s Mask > Wind Waker represents the greatest sustained run in video game history. But then…I stopped liking the games. They began to annoy me. They no longer trusted me to play them. Exploration gave way to exposition. Problem solving gave way to following instructions.

I stopped caring.

So Breath of the Wild came out, and people liked it. I was glad they did. I was no longer convinced that I would.

What I failed to realize is that it addressed every single one of the concerns I ever had with the series. While I was quite fond of a few helper characters (Navi, Tatl, The King of Red Lions), it was nice to play an entire game without anyone bleating answers over my shoulder. While the overall lack of combat difficulty in some other recent titles never bothered me, it was nice to play a game in which I really did need to pay attention to everything I did in every fight, lest I wind up dead at the bottom of a ravine. And while I never really minded the predictability of dungeon weapons, it was nice to play a game in which there were so few of them, and I instead had to scrap by with whatever I could scavenge.

Breath of the Wild is clearly a Zelda game, and yet it’s so little like what Zelda has come to represent. It’s Zelda stripped down to its elements, and then built back up with a much stronger framework. Playing it was revelatory. It was the Zelda game I had always wanted, and yet never expected. And while a few areas felt disproportionately hard, I get the sense that I could have made them much easier on myself had I visited some other areas first and stocked up on better gear. That’s something I’ll keep in mind for my next playthrough.

What I really loved about Breath of the Wild was how much fun everything was. Not just the battles and dungeons, but everything. Sitting at a campfire cooking meals should have been dull, but watching the ingredients pop and sizzle in the pan was actually pretty hypnotic. Hiking from town to town revealed new things on the journey each time, whether it was fellow travelers, monsters, or environmental puzzles to waylay me. Even getting around — the singular act of motion — was thrilling. Paragliding, climbing, surfing down sheer rockfaces on my shield…everything was fun.

I don’t get it. I really don’t. Breath of the Wild is nothing like what I would have described as my ideal Zelda game, and yet it’s the perfect Zelda game. It’s engrossing. It’s rich in detail. It’s alternately hysterical and brutal. It’s cute and it’s shocking. It’s personal and it’s cruel. It’s overpowering and it’s empowering.

It’s a great game, and as much as I love Nintendo, it’s a more mature one than I honestly thought they were capable of creating. (Short of creating an all-new IP, at least.) It represents a brave new step forward, and a massive gamble on rendering a reliable formula almost completely unrecognizable.

The payoff was massive. Breath of the Wild was everything the best games should be, and the only thing I truly dislike about it is that I’ll never be able to play it for the first time again.

2) Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice

As far as video game titles go, you can’t get much more generic than Hellblade, which is why I was not only surprised it was so unique, but was also surprised that it’s an incredible, respectful, admirable portrayal of mental illness. Surely the best and most accurate in video games by a wide margin.

I didn’t know that aspect of the game even existed when I started playing it. I’d heard good, vague things about Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice, so I tried not to read much about it, knowing I’d eventually give it a spin. All I knew (or at least retained) was that you played as Senua, who traveled into a dangerous land with the severed head of her boyfriend attached to her hip.

So, fine. Explore this crazy world, fight these crazy monsters, finish this crazy quest.

I didn’t expect that “crazy” would be such a defining aspect of the game, though.

The very first credit in Hellblade goes to a mental health advisor. The moment I saw that, I knew the game was either destined to become one of my favorites, or one of my most hated. Fortunately, it almost immediately established itself as the former. As somebody who struggles with mental health issues — anxiety being the relevant cocktail ingredient here — the swirling, conflicting, smothering narration that precedes, overlaps, and follows every action Senua undertakes is all too familiar to me. So much so that I had to stop playing the game at several points, just to recover from it.

Senua is plagued by voices. Real? In her head? It doesn’t matter. She hears them. They criticize her. If she backtracks, they laugh and mock her for getting lost. If she takes damage in battle they give up on her and write her off as dead. If she teeters on a small ledge over a steep drop they tease her and assure her she won’t make it. They are relentless.

This is what life is like for me. Not the same voices, not the same words, but the same experience. I’ve never seen it represented so accurately, and I believe that the accuracy is helped a lot by it being attached to an interactive experience. Watching a film about mental health issues may be instructive, but experiencing them in response to your actions, hearing every little thing you do wrong get criticized, learning to second guess yourself in anticipation of oncoming criticism, diminishing your own accomplishments, becoming overwhelmed by voices that are in your head and which you cannot control…

It’s nightmarish, and Hellblade respectfully renders that nightmare. It’s even smart enough to let the voices conflict at times with each other. Some seeming to offer genuine encouragement while the rest tear you down…but you know it won’t be long until they’re all on the same side again, their faith in you completely lost, their unwillingness to believe you’ll ever accomplish this or any goal you set for yourself. Reminding you of your failures with every step you try to take forward.

It’s remarkably affecting, and I think very helpful to players who don’t suffer from or understand mental illness. I’ve had friends (often very good ones) who don’t understand why I can’t hang out whenever they’d like to, or why I shut down in certain social situations, or why I worry so much about things that don’t even register to them. Some of them get frustrated. I can’t blame them. But I do think a game like this is extraordinarily valuable. It translates the language of mental illness from something they can’t see or hear into something they can actively experience and feel. Hellblade would be great for that alone.

But it’s also an impressive game in general. It’s beautiful, in a haunting, desolate way. The sound design is incredible. The swordplay is deceptively rich. And Senua herself is probably the single best looking video game character I’ve ever seen. Not exactly in terms of attractiveness, but in terms of…humanity. She looks real. I’m not controlling an avatar…I’m controlling Senua. A person. A person who moves and reacts and responds realistically. She’s the most human video games character I’ve ever known…so expressive. So unique. So fragile.

Early in my game, the voices were correct. I didn’t make it across a narrow ledge. I fell and died. And I didn’t think, “Oh well, I’ll try again.” I thought, “I killed Senua.” And I felt awful.

That alone set Hellblade apart from anything else I played this year.

1) Persona 5

A few years ago, my good friend Matt practically bullied me into playing Persona 3 and Persona 4. I’ll be grateful to him forever as a result, not least because having these games under my belt allowed me to participate in the brilliant wave of anticipation for Persona 5.

The game suffered delay after delay, with very little information or screenshots being communicated through the official channels. I don’t think anyone truly expected that the project was dead or dying, but we knew almost nothing beyond the broadest strokes what Persona 5 was even going to be.

Then it was released, and it was a strong contender for the most stylish video game in history.

Everything about it was so…correct. The character designs, the animations, the voice acting, the environments, the battle system…and, yes, these things all built upon and learned from the Persona titles that came before, but they still felt so right here. They were the latest link in an evolutionary chain, but they were also uniquely Persona 5. Held together by a striking black and red color scheme and a modern pulp aesthetic, every moment of the game is beautiful, and beautifully designed.

It also may have the best soundtrack of any game, period. I’m dead serious. In fact, I think it would be unfair to compare many other game soundtracks to this one, as it would be a sorely mismatched fight. I very much enjoyed Persona 3‘s hiphop and Persona 4‘s J-pop, but Persona 5‘s smokey, jazzy, chanteuse numbers are on a plane of their own.

Overall, I don’t think I enjoyed it as much as I did its two predecessors, but any complaints I have would be minimal (as you can probably guess from the fact that it’s still the best game I played all year). It’s a fun, often dark, sometimes silly time…an RPG of epic scope crammed into the space between school nights, one in which the beating back of evil has to be scheduled around exams and class trips, one in which life or death dalliances with your friends won’t keep you from flirting with that cute girl you know, because whether you survive or not, you’re only young once…

It’s an adorable game full of impressively rounded characters, and while I’d argue that a few of them miss their marks, so many of them land well enough that you’re never far away from the next engrossing backstory. Each of the characters — major and minor alike — are haunted by some mistake in their past. Spend enough time with them, and you might just get to see them move, finally, forward. Persona 5 is a game full of isolates, full of characters who want only to connect, but don’t see themselves as capable or deserving of connection. Gradually, one by one, you can help them to tear down their walls…achievements even more satisfying than slaying the biggest monsters.

There’s so much to love here. Ryuji, the first friend you make at your new school, seems like your run-of-the-mill knucklehead, but soon comes to reveal real vulnerability and loyalty. There’s an overachieving honor student who is asked to spy on you, and if you pay attention while roaming the city, you can spot her doing just that. And Futaba’s story arc is probably the most affecting and heartfelt in the series…which is saying something. I found myself genuinely moved by her struggles, and being very defensive of her throughout the rest of the game.

She was human. As so many of these cartoon characters revealed themselves to be human.

I’ve heard many people say that Persona 5 is too long. And, you know what? They’re probably right. But just like every Persona game, it also feels just a bit too short. By the time it’s over, however long you had together, you still wish you could have just one more day with your friends.

And there you have it. My top 10 games of 2017-ish. What did I miss out on? Let me know; I may feature those games in my best of 2028 list.

(Screengrab burgled with permission from Full House Reviewed.)