I’m going to open my discussion of Star Trek: The Original series season two with some unexpected disappointment. Why not, eh?

My journey through Star Trek has taken place almost entirely offline. You got my summary post of season one, and I’ve exchanged messages with a few friends, but nearly all of my discussion about the show has occurred in reality, with the friends and coworkers I interact with normally.

They’ve been very — impressively, even — good at allowing me to come to my own conclusions. Very, very rarely do they tell me ahead of time of a development to come or how an episode is overall received by fans. When it does happen, it’s been stuff that’s pretty obvious. (Chekov joining the cast for the second season, “The City on the Edge of Forever” being rightly beloved, etc.) Beyond that, they’ve volunteered very little that I didn’t bring up — or question — myself in the course of conversation.

And yet — and yet! — there is one thing I heard many times over: Season two is a huge improvement over season one.

And yet — and yet! — there is one thing I heard many times over: Season two is a huge improvement over season one.

This made so much sense to me that I didn’t really think twice. Honest question: Can you name many successful series in which the second season did not represent a notable improvement over the first?

In a collaborative medium — such as television, of course — there’s a lot to learn. No matter how well you plan ahead of time, you’ll face a deluge of curveballs once things are underway.

Actors will bring with them their own talents and limitations. Costumes and sets will be limited by a budget, which itself is likely to fluctuate. Continuity (correctly, in my opinion) goes out the window as the writers discover better, more fruitful ideas as the series progresses. Tight deadlines prevent you from producing a show as strong as you might like. Injury or illness takes people out of the rotation when you need them most.

And that’s just a small sampling of very superficial considerations. My point is that you can’t predict or account for every obstacle you will face, and that’s especially the case in season one of whatever show you’re making.

And that’s just a small sampling of very superficial considerations. My point is that you can’t predict or account for every obstacle you will face, and that’s especially the case in season one of whatever show you’re making.

By season two, you’ve necessarily had to adjust and account for those things at least once. New obstacles will certainly present themselves, but you’ve at least got a handle on the old ones. The pool of “unknowns” has shrunk. You are in a position now to create something that is more in line with the vision in your head.

So of course season two of The Original Series would be a huge step forward. I could have guessed that on my own, but it was nice to have it confirmed by long-time fans. It meant that I had something to look forward to.

Then I watched season two, and…man, I am not sure that I agree.

I do believe it’s better. Full stop. But I don’t think it’s better to any degree that is worth mentioning.

The great episodes don’t really stand above the great episodes from season one. The lousy episodes are no better than their earlier equivalents, either. And I’m not sure that there are a larger number of great episodes or a smaller number of lousy ones.

The great episodes don’t really stand above the great episodes from season one. The lousy episodes are no better than their earlier equivalents, either. And I’m not sure that there are a larger number of great episodes or a smaller number of lousy ones.

I think I can say that the baseline level of competence has risen, but not enough that it has any measurable difference on the quality of the season as a whole.

Of course, I ended up liking season one — quite a lot — so this is a relative disappointment only. I was prepared for season two to blow the previous season away, and it really, truly did not. I’d love to know what folks believe sets season two so high above season one, because as a newcomer I’m kind of baffled.

What I can say for sure is that the pacing is, on the whole, much better this time around.

Better pacing doesn’t turn a bad story into a good one (nor does poor pacing turn a good story into a bad one), but the journey is much more enjoyable for it. Rarely did I feel that an episode dragged (“The Immunity Syndrome” aside, as it was clearly intended to drag and is just as clearly fucking unwatchable), whereas the majority of episodes in season one had at least one dreary stretch that had me checking my watch.

Better pacing doesn’t turn a bad story into a good one (nor does poor pacing turn a good story into a bad one), but the journey is much more enjoyable for it. Rarely did I feel that an episode dragged (“The Immunity Syndrome” aside, as it was clearly intended to drag and is just as clearly fucking unwatchable), whereas the majority of episodes in season one had at least one dreary stretch that had me checking my watch.

But that’s about the only real improvement I can cite. I’m genuinely curious to know what other folks think.

The most obvious change is the addition to the cast of Chekov, played by the fucking adorable Walter Koenig. I love Chekov, but I can’t imagine that his debut is the reason people rate season two so highly.

Regardless, he’s an excellent addition. Everybody on the Enterprise has their lighter moments, but young Chekov has a far higher percentage of them, which means that nearly all of his scenes are pleasant and entertaining.

Regardless, he’s an excellent addition. Everybody on the Enterprise has their lighter moments, but young Chekov has a far higher percentage of them, which means that nearly all of his scenes are pleasant and entertaining.

His youth also allows him to illustrate something we saw very little of in season one: a lack of discipline. Chekov is intelligent and accomplished (is there a greater intellectual honor than filling in for Spock whenever necessary?), but he lacks the gravity and authority of his older comrades.

In season one we definitely met some flawed crewmen, but Chekov registers more as someone who just hasn’t had enough time to iron out his flaws. He’s competent and capable, but needs a bit of polish. It’s an interesting kind of character to have as a fixture on the bridge.

In my season one post, I spilled a lot of ink wondering why it took until season two for anyone to think to fill the navigator’s chair with a single, recurring character. Ultimately, I let the issue drop because I knew this would happen with Chekov in season two.

…and yet, now that I’m here, I’m not even sure that that’s the case.

Chekov’s arrival coincides with Sulu’s absence. George Takei was unavailable for many episodes because he was off filming a movie, apparently. So I wonder, was Chekov introduced — as I’d assumed — because it was wasteful to invent / cast a different navigator for every episode? Or was he introduced because Sulu, the only other recurring character on that part of the bridge, would be absent for much of the season?

Chekov’s arrival coincides with Sulu’s absence. George Takei was unavailable for many episodes because he was off filming a movie, apparently. So I wonder, was Chekov introduced — as I’d assumed — because it was wasteful to invent / cast a different navigator for every episode? Or was he introduced because Sulu, the only other recurring character on that part of the bridge, would be absent for much of the season?

The amount of puzzlement the navigator’s chair has brought me is beyond measure, and I won’t belabor the point any further, but good lord, what a strange situation.

This is a case in which the BluRay running order is clearly much different from production. Surely Takei would have been absent for one long stretch of recording, but in my experience watching season two, Sulu is there one week, Chekov is there the next, then Sulu, then Chekov. Rarely are they both in the same episode; one really does feel like a replacement for the other.

That’s a bit disappointing, because some of my favorite material ended up being the rare interactions between the two.

Chekov and Sulu have this natural, recognizable sort of default camaraderie that comes from sitting next to each other every day. They don’t necessarily know each other very well, but they share little quips and commiserations out of proximity alone. They are coworkers who don’t dislike each other but who also — almost certainly — spend no time together after the shift ends.

Chekov and Sulu have this natural, recognizable sort of default camaraderie that comes from sitting next to each other every day. They don’t necessarily know each other very well, but they share little quips and commiserations out of proximity alone. They are coworkers who don’t dislike each other but who also — almost certainly — spend no time together after the shift ends.

That, to me, is so much more interesting than two lifelong chums would be. And it’s probably more believable, as well.

Surprisingly, Nurse Chapel becomes a semi-regular character in season two. She existed in season one, but only barely, appearing in just one or two episodes (if I remember correctly), and those were early in the season.

I was glad to see that a character who seemed forgotten ended up playing a larger role this time around. I’d be lying if I said she got all that much to do, but her presence meant that we could get scenes in sickbay whenever Bones was out gallivanting with the landing team.

Speaking of Bones, the only other casting change that I noticed was the overdue promotion of DeForest Kelley to the main credits. He appears in every episode now, which is very welcome as far as I’m concerned. The guy is still my pick for MVP from both an acting and characterization standpoint. There’s never a scene with Bones that is not elevated for his presence.

Speaking of Bones, the only other casting change that I noticed was the overdue promotion of DeForest Kelley to the main credits. He appears in every episode now, which is very welcome as far as I’m concerned. The guy is still my pick for MVP from both an acting and characterization standpoint. There’s never a scene with Bones that is not elevated for his presence.

And since I’m destined to gush about Kelley / Bones all over again, I might as well tie it into my favorite thing about the season: its willingness to explore character.

We had plenty of opportunity to discover who these people were in season one, and I’d argue that just about all of the characterization was effective and well handled. Season two, though, gets to take it a step further. Since we already know who these people are, we are able to delve into what makes them that way.

Perhaps because Bones was already damned well realized in the first season, we don’t get too much that centers around him here. His “big” episode is “Friday’s Child,” which I quite liked in spite of its obvious flaws.

The crew journeys to a planet that Dr. McCoy has visited in the past, where he attempted to bring medical knowledge to the civilization there. His experience of this culture — his understanding of their nature and their customs — proves invaluable in a way that I thought was great. He even gets to do some excellent work with guest star Julie Newmar, seeing him pinched between his obligations as a doctor and his obligations as a visitor on behalf of Starfleet.

The crew journeys to a planet that Dr. McCoy has visited in the past, where he attempted to bring medical knowledge to the civilization there. His experience of this culture — his understanding of their nature and their customs — proves invaluable in a way that I thought was great. He even gets to do some excellent work with guest star Julie Newmar, seeing him pinched between his obligations as a doctor and his obligations as a visitor on behalf of Starfleet.

Overall, though, Bones shines mainly in support roles. I’m hoping we get at least another episode dedicated to him in season three, because I really do think the character can carry more than he’s been given, but the guy is so great as a sidekick that I can’t complain.

He’s insightful and hilarious by turns. The hardest I’ve laughed in a while came in “Bread and Circuses,” when he is tossed into a gladiatorial fight to the death. His opponent — who is a friend — goes easy on him, but tells Bones to at least defend himself. “I am defending myself!” he responds, and Kelley’s delivery is absolutely perfect. There’s surprise, frustration, and fear behind it, and yet it’s still comical.

In fact, “Bread and Circuses” might be one of his best episodes, even if his presence there is no larger than in most others.

There’s a lovely scene in which he and Spock are imprisoned together, and he’s worried to the point that he lets his gruff demeanor fall just enough that he’s able to speak to Spock like a friend, with genuine warmth. Spock responds…well, like Spock. Cold and detached, same as ever. “I’m trying to thank you, you pointed-eared hobgoblin,” McCoy says, and it’s funny and emotional at the same time.

There’s a lovely scene in which he and Spock are imprisoned together, and he’s worried to the point that he lets his gruff demeanor fall just enough that he’s able to speak to Spock like a friend, with genuine warmth. Spock responds…well, like Spock. Cold and detached, same as ever. “I’m trying to thank you, you pointed-eared hobgoblin,” McCoy says, and it’s funny and emotional at the same time.

I’ll give the writing its due credit here, but Kelley absolutely elevates this stuff, giving it resonance that works far beyond the words typed onto a script. (However good those words might be.)

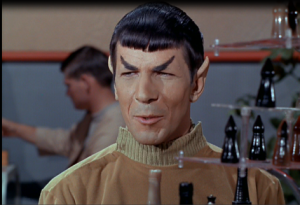

Spock gets a pair of important episodes about who he is, and they’re both among the season’s best. Each of them focuses on the struggle between his Vulcan half and human half, and each of them tips the balance in a different direction.

“Amok Time” is by far the more famous one, showing his Vulcan urges completely overtake his humanity to the point that he finds himself in a fight to the death with his best friend. (McCoy is the hero of this one, settling matters in a way that’s both entirely out of left field and completely appropriate to the situation. Just need to toss my man Bones another high five.)

It ends with Spock asserting his human side, in spite of the fact that he knows his fellow Vulcans won’t understand. Having lost his betrothed to another man, he congratulates him, but then adds, “After a time, you may find that having is not so pleasing a thing after all as wanting. It is not logical, but it is often true.”

It ends with Spock asserting his human side, in spite of the fact that he knows his fellow Vulcans won’t understand. Having lost his betrothed to another man, he congratulates him, but then adds, “After a time, you may find that having is not so pleasing a thing after all as wanting. It is not logical, but it is often true.”

It’s a pained and painful acceptance of the part of himself he works hardest to keep hidden, and it’s executed brilliantly.

The other one, “Journey to Babel,” approaches things from the other direction. Here, it is Spock’s humanity that is tested to the point of agony.

His father falls ill and is in need of a transfusion, which only Spock can provide. Easy enough, except that with Kirk indisposed, Spock is in command of the Enterprise. No Vulcan would shirk his duty for the sake of something as sentimental as saving a loved one. Spock’s father is one person, after all; there are hundreds aboard the Enterprise. Clearly the logical thing is to fulfill your obligation to them. No Vulcan would disagree. In fact, Spock’s father won’t even disagree as he finds himself at death’s door.

But that human side of Spock — personified in this episode by his human mother — won’t let the matter remain settled. He ultimately gives into this side, but bonds with his father afterward by picking on her (in a genuinely good-natured way) for her tendency to put emotion over logic. After an episode of human struggle, he snaps back to being a Vulcan.

But that human side of Spock — personified in this episode by his human mother — won’t let the matter remain settled. He ultimately gives into this side, but bonds with his father afterward by picking on her (in a genuinely good-natured way) for her tendency to put emotion over logic. After an episode of human struggle, he snaps back to being a Vulcan.

Each episode raises the question of Spock’s nature, and each one provides a different answer. It’s interesting, and though I far prefer “Journey to Babel,” they’re both handled extremely well, with a level of care and intelligence I wouldn’t have expected.

Even Scotty — who I have to assume was an unexpected breakout character last season — is explored in a pair of episodes. In “Who Mourns for Adonais?” we see him fall in love with a woman who doesn’t quite feel the same way toward him, and he’s willing to sacrifice himself to keep her safe. In “Wolf in the Fold,” we see him work through some off-screen trauma, though it does land him in a different kind of hot water, which ends up being even worse.

Then there’s “The Trouble With Tribbles,” which sees him calm and clear-headed as a rowdy group of Klingons insults their captain…but he throws a punch the moment they insult his beloved ship.

His runaway highlight of the season though is his attempt to outdrink an alien visitor in “By Any Other Name.” The drunk acting between the two characters is a fucking delight. It’s played for obvious comedy, but there’s something genuine and identifiable about the way they go from being distant to being pally to seeming like they’re about to fight before they both pass out.

His runaway highlight of the season though is his attempt to outdrink an alien visitor in “By Any Other Name.” The drunk acting between the two characters is a fucking delight. It’s played for obvious comedy, but there’s something genuine and identifiable about the way they go from being distant to being pally to seeming like they’re about to fight before they both pass out.

Absolutely wonderful stuff.

Kirk, understandably, gets the most attention as a character, and the criticism of Shatner’s acting that I’ve been hearing for years seems even further divorced from reality.

I’ll put it right out there: I love Kirk. He seems to have been written in a way that positions him as a role model, but also, crucially, as an achievable one.

He’s not infallible; he is a human being as flawed as any other, but he works through his flaws. He earns every ounce of respect and admirability he commands. Kirk doesn’t coast on his good looks or his charm, and he doesn’t take his success for granted.

All of which is very interesting, because season two explores him mainly through other characters. Characters in positions similar to Kirk, but who have let their flaws take over, or who have thought too much of themselves, or who have taken something for granted with disastrous results.

We encounter a number of other members of Starfleet who Kirk remembers fondly, and then we see just what could happen if Kirk were to fail to think through the results of his actions, or let himself take the easy way out at any point.

We encounter a number of other members of Starfleet who Kirk remembers fondly, and then we see just what could happen if Kirk were to fail to think through the results of his actions, or let himself take the easy way out at any point.

In “Bread and Circuses,” Captain Merik turns his crew over to a brutal world because he doesn’t have the integrity to fight back…and though he finds himself rewarded for doing so, it’s hollow, and feels like no kind of victory to him.

In “Patterns of Force,” a historian attempts to provide a framework for order to a chaotic society, without quite thinking far enough ahead to realize that Nazi Germany might not be the best example.

In “The Omega Glory,” Captain Tracey has manipulated a civilization into a state of eternal conflict simply to keep himself safe after being stranded among them.

All of these examples suggest alternate paths that Kirk could follow. He won’t, but he could. What’s more, each of these men could be said (to varying degrees) to have been doing what they felt was right, given their difficult situations. Kirk follows his gut on a weekly basis. Surely it’s just a matter of time before that gut leads him to the wrong decision…

In each of these cases, things have spiraled out of control. In each of these cases, the men in question probably got to enjoy a good, long stretch of believing everything has worked out correctly. In each of these cases, we meet them after they can no longer convince themselves that that’s the case. They’re lost, and the best they can do is try endlessly to justify to themselves what they’ve done, because nobody else is around to listen.

In each of these cases, things have spiraled out of control. In each of these cases, the men in question probably got to enjoy a good, long stretch of believing everything has worked out correctly. In each of these cases, we meet them after they can no longer convince themselves that that’s the case. They’re lost, and the best they can do is try endlessly to justify to themselves what they’ve done, because nobody else is around to listen.

But these are all hypothetical paths for some alternate version of Kirk to take. There’s another alternate Kirk we meet this season, and it’s far less hypothetical.

In “The Doomsday Machine,” we meet Commodore Decker, who has lost his entire crew and his ship to a creature of unknowable power. He made the decision to beam them down to a planet, in the hopes that he could save them. He could not; when Kirk finds him, he is the lone survivor of the attack.

Decker made the best decision he could possibly have made at the time, but that didn’t matter. It was a no-win situation, and he lost. The experience broke him. It’s a tragic performance that does excellent work selling just how busted up this man is, just how much he’s lost, just how tormented he feels about outliving the crew that was entrusted to him.

He’s beamed over to the Enterprise for bed rest while Kirk attempts to get the disabled ship up and running. While there, the Enterprise spots the beast…and Decker, out of his fucking mind, assumes command.

He’s beamed over to the Enterprise for bed rest while Kirk attempts to get the disabled ship up and running. While there, the Enterprise spots the beast…and Decker, out of his fucking mind, assumes command.

He outranks everybody else on the ship. There’s nothing they can do aside from follow his orders. He single-mindedly pursues the monster that could — and certainly will — eat the Enterprise for lunch. The desperate glances between crewmen who reluctantly carry out the orders that will bring them to their deaths are chilling.

They are marching, step by step, into their graves, and there is nothing they can do.

In the end, surprise surprise, Kirk comes back and takes over. The entire crew is understandably relieved to have someone sane in the captain’s chair again.

They all mop their brows and say, “Whew!” A close call, but they will never serve under Decker again. Roll credits.

Then, many episodes later, we have “Obsession.”

Here, Kirk encounters a beast that killed his crewmates early in his Starfleet career. He always believed he made the wrong decision, though he was found to have not been at fault for the disaster. Regardless, Kirk unexpectedly crosses paths with it again, and is determined to destroy the thing this time. He orders the ship onward, toward the unstoppable beast, against all reason, against the counsel of his most trusted friends, against the protestations of his crew…

Here, Kirk encounters a beast that killed his crewmates early in his Starfleet career. He always believed he made the wrong decision, though he was found to have not been at fault for the disaster. Regardless, Kirk unexpectedly crosses paths with it again, and is determined to destroy the thing this time. He orders the ship onward, toward the unstoppable beast, against all reason, against the counsel of his most trusted friends, against the protestations of his crew…

And suddenly they are serving under Decker again. But it’s Kirk. Which means they can’t sit around waiting for Kirk to beam over and get the crazy man out of the chair. Nobody else is coming.

Kirk meets many alternate versions of himself — versions with different appearances, ranks, histories, but versions of himself nonetheless — and gets to end each episode thankful that he’d never make the decisions that would get him to that point.

Except in the case of Decker, because he makes exactly the same decisions, endangers his own crew in exactly the same way, failing to learn one of the most important lessons this season tried to teach him.

In my rankings below, I honestly wasn’t sure whether to place “The Doomsday Machine” or “Obsession” higher. They chart similar ground and they each do so excellently. You can swap those two around if you like; I won’t mind.

In my rankings below, I honestly wasn’t sure whether to place “The Doomsday Machine” or “Obsession” higher. They chart similar ground and they each do so excellently. You can swap those two around if you like; I won’t mind.

Ultimately it came down either to giving the nod to a truly fantastic guest character, or to the horror of seeing Kirk drift so easily and naturally into the status of “cautionary tale” for whatever captain would happen to come along next. I went with the latter. I’d be no less satisfied with the former.

We get some other confirmations of flaws in Kirk along the way, though they aren’t given nearly as much time as we get in “Obsession.”

In “The Deadly Years” we see him clinging to command of the Enterprise well after he’s lost his faculties and mental acuity. In “The Ultimate Computer” we see him fret about losing his job to a machine, with McCoy both comforting and chiding him: “We’re all sorry for the other guy when he loses his job to a machine. When it comes to your job, that’s different. And it always will be different.” (Guys, McCoy is fucking great.)

Possibly not coincidentally, that episode also gives us an alternate Kirk: Dr. Daystrom, another hotshot who showed promise young, and then became desperate to avoid falling into irrelevance.

Possibly not coincidentally, that episode also gives us an alternate Kirk: Dr. Daystrom, another hotshot who showed promise young, and then became desperate to avoid falling into irrelevance.

All of which sounds like this season was pretty excellent, right?

Well…yeah! Kind of. For the most part. At times.

Not all of the episodes I’ve highlighted above are actually good…it’s just that, as with season one, even the worst episodes have something to recommend them.

Also like season one, but which I didn’t discuss there, the episodes have a strange tendency to take a hard left turn at various points, becoming something else entirely.

“The Omega Glory” is a particularly egregious example; it begins promisingly, with the Enterprise finding a derelict ship full of crystalized crewmen. What happened? It’s a good mystery and, as cheap as it certainly was, a nice visual. Then we take a hard left turn to a planet on which Americans and Communists both sprouted up independently of Earth and Kirk explains their — also identical — U.S. Constitution to them in what I hope to Christ is the most embarrassing thing Star Trek ever does.

“The Omega Glory” is a particularly egregious example; it begins promisingly, with the Enterprise finding a derelict ship full of crystalized crewmen. What happened? It’s a good mystery and, as cheap as it certainly was, a nice visual. Then we take a hard left turn to a planet on which Americans and Communists both sprouted up independently of Earth and Kirk explains their — also identical — U.S. Constitution to them in what I hope to Christ is the most embarrassing thing Star Trek ever does.

“Wolf in the Fold” is a strange one, too. It starts with a decently effective whodunit, at the heart of which is poor, baffled Scotty. He’s the only suspect in a series of grisly murders. We know he didn’t do it, of course, but we can still have some fun learning how, exactly, he was framed. Well, the joke’s on us because after a hard left turn the episode is about the ghost of Jack the Ripper who now haunts the Enterprise‘s computers.

It’s not always a bad thing. I really liked “By Any Other Name,” but I don’t know if I’m impressed or confused by how easily it swings from being an episode with a genuine threat to being overtly comic. Both halves work well on their own, but it really feels as though everyone involved with the first half of the episode died suddenly in their sleep and a completely different set of folks were brought in to finish it.

That about does it for anything I can really say with any thought behind it, but I do have a few other, scattered thoughts.

Firstly, Harry Mudd got robbed. Roger C. Carmel is an absolute riot in the role, but “I, Mudd” and last season’s “Mudd’s Women” are abysmal pieces of television. I’m told he doesn’t appear in season three, and that’s unfortunate because if any character needs an episode good enough to redeem him, it’s poor old Mudd. The guy should have been the show’s Sideshow Bob, but it feels like the writers just sort of shrugged and figured Carmel could carry his episodes on charisma alone. I can’t blame them — dude is amazing — but come on.

Firstly, Harry Mudd got robbed. Roger C. Carmel is an absolute riot in the role, but “I, Mudd” and last season’s “Mudd’s Women” are abysmal pieces of television. I’m told he doesn’t appear in season three, and that’s unfortunate because if any character needs an episode good enough to redeem him, it’s poor old Mudd. The guy should have been the show’s Sideshow Bob, but it feels like the writers just sort of shrugged and figured Carmel could carry his episodes on charisma alone. I can’t blame them — dude is amazing — but come on.

Secondly, I had somehow gotten it into my mind that “The Gamesters of Triskelion” was the episode with television’s first interracial kiss. I was wrong — that must happen in season three at some point — but I do sort of wish it had happened in this episode. It would have been one of the only redeemable things about that fucking mess.

Thirdly, “Mirror, Mirror” is a god-damned masterpiece. I think I still prefer season one’s “Balance of Terror,” but I was genuinely impressed by every last one of the choices made in “Mirror, Mirror.” It’s not surprising to me at all that the concepts of mirror universes and evil versions of characters became so common after this. Many Star Trek episodes have solid concepts, but this one nails the execution as well anything possibly could. It’s as brilliant as “Catspaw” is dumb. And “Catspaw” is really, deeply, profoundly dumb.

Fourthly, I prefer the theme tune without vocals. No idea how much sacrilege I’m practicing here but, well, there ya go.

Finally, I’m sorry, I almost touched upon this in my season one review but I can’t keep it inside anymore: Everyone on this show is hot as fuuuuuuuuck.

Finally, I’m sorry, I almost touched upon this in my season one review but I can’t keep it inside anymore: Everyone on this show is hot as fuuuuuuuuck.

Shatner is gorgeous, and he’s gorgeous in a way that doesn’t lock him into “1960s heartthrob” status. He is just a genuinely great looking human being. Spock isn’t my cup of tea, but his beard in “Mirror, Mirror” absolutely had me swooning. Scotty, Sulu, and Chekov are all adorable in such very different ways. Uhura is quite possibly perfect; if there is a straight man out there who isn’t attracted to her, I’d have to ask what it is they find attractive about women; she certainly seems to satisfy every possible answer to that question. And Bones is probably the least conventionally attractive character on the show but let me be very, very clear about the fact that I would make out with him and I’d do it proudly.

Whew. Okay. Anyway, point is, season two was pretty great, but season one wasn’t much less great. If season two’s quality was inflated, I’m glad to hear it; all I’ve heard about season three is how much of a step down it is, so maybe that will turn out to be an exaggeration as well.

I’ll find out soon enough, I suppose. I’ll be diving into that next. And I can finally reveal that, in all honesty, I only started watching Star Trek so I could eventually see the legendary “Spock’s Brain.”

I’ll find out soon enough, I suppose. I’ll be diving into that next. And I can finally reveal that, in all honesty, I only started watching Star Trek so I could eventually see the legendary “Spock’s Brain.”

Anyway, everything above is just my opinion and you are more than welcome to disagree. In fact, please do! I’d like to end on some indisputable fact, though, so here is every season two episode of Star Trek: The Original Series ranked from worst to best.

26) Catspaw

25) Who Mourns for Adonais?

24) The Immunity Syndrome

23) The Changeling

22) The Gamesters of Triskelion

21) The Omega Glory

20) A Private Little War

19) The Apple

18) Assignment: Earth

17) Return to Tomorrow

16) A Piece of the Action

15) I, Mudd

14) Wolf in the Fold

13) Patterns of Force

12) Metamorphosis

11) Friday’s Child

10) Bread and Circuses

9) The Deadly Years

8) Amok Time

7) The Trouble with Tribbles

6) By Any Other Name

5) The Ultimate Computer

4) The Doomsday Machine

3) Obsession

2) Journey to Babel

1) Mirror, Mirror

Images throughout courtesy of Warp Speed to Nonsense.