Mega Man had never gone more than two years between games, but after Mega Man 8 — and the one-off experiment that was Mega Man & Bass — the series went a decade. Once an industry mascot right up there with Mario, Link, and Sonic, Mega Man just…stopped. The saddest part was that nobody really missed him.

The world kept turning, no darker or more slowly without him. The industry trudged forward just fine. Even its developer, Capcom, had moved onto other series that kept its fortunes strong. Resident Evil, Devil May Cry, Dead Rising, Monster Hunter, Phoenix Wright: Ace Attorney, and lots of others were released at a steady clip and to positive reception. To paraphrase Clarence Oddbody, Mega Man had been given a great gift…a chance to see what the world would be like without him. And it turned out the world was just fine.

Mega Man was relegated to the chambers of memory. If you wanted to, you could dust off your old NES and rip through whatever game or games of his you remembered most fondly, but it was far more likely that your attention was now elsewhere. Every so often you’d talk with a friend about the games of your youth, and Mega Man would come up. You’d reminisce about him. You’d laugh about the good times and bad. But like all memories of those you’ll never see again, you’d tuck them away again and focus once more on the here and now.

Mega Man’s disappearance didn’t interfere with my life any. I had other things on my mind. I was finishing high school. Then I was in college. I was dating. I was working, often at multiple jobs. I was developing as a writer. I was moving out. I was learning what I wanted out of life, and I was trying to figure out how to get it. I was growing up, because I had to.

For a good long while I never had to worry about where my food or shelter would come from. Then, overnight, I did, and the amount of time I could devote to extravagances was sorely reduced. Had Mega Man continued on his yearly release schedule, there would have been 20-odd games I wouldn’t have had the time to play.

In short, his absence wasn’t felt. I was able to say that about a lot of figures from my childhood. I valued the time we spent together, but I was somewhere else now. I wished them well, but there was no time for looking back.

Until, of course, there was.

Around 2007, I was still working hard — I had to be — but I was no longer pennies away from bankruptcy. I built up a savings. I found a great place to live in a different state. I had an incredible job. I found a new circle of friends. Things were…okay. The stressors and worries that had defined me for my entire adult life…weren’t there anymore. At some point I stopped. I caught my breath. And I realized I was okay.

I had time again. I had the money and space to devote to the things that I wanted to pay attention to. I started revisiting the things I had loved unquestioningly as a child. Books, movies, music, TV shows. It was during this period that I launched my first website as well, giving me a place to write about those things and more. This goes back many years, but I don’t need to point out that this is still where I am today. This is what I do. I study. I report. I read too deeply into things.

One of my major purchases at the time was a Wii, which was a bit surprising, as I had been out of the video game loop for quite a while. But I was interested in it. Not for Wii Sports. Not for Super Mario Galaxy. Not for whatever Zelda game was guaranteed to come along.

No. What won me over was the Virtual Console.

It’s amazing how quaint the concept feels now, what with digital downloads and emulation becoming less the exception and more the rule, but I remember looking through a listing of classic games available for purchase on the Wii and feeling blown away. I could play Super Mario 64 again? Well, what am I waiting for?

I enjoyed the Wii, and I think it had some incredible games throughout its lifespan. But the crisper visuals didn’t win me over. The motion controls didn’t win me over. The chance to play Mario Kart online didn’t win me over. What won me over was the opportunity to go backward. To rediscover. To rebuild — albeit digitally and with strong limitations — the same library of games I had growing up. The ones I loved. The ones I didn’t love. The ones that were too hard for me. The ones rooted so deeply in my mind that I could replay them from memory, uncovering every secret again along the way.

People complained about the prices; I remember that very well. I thought and still think they were crazy. $5 for an NES game was a steal. $8 for a SNES game. These were games my parents couldn’t easily afford for me when I was little, and now they were priced lower than a meal at a fast food restaurant. Didn’t people realize what a great time to be alive this was?

I downloaded so many classic games, most of which held up just as well as I could have hoped. And since they were so cheap, I bought plenty of games I never got to play as a kid, discovering many gems along the way that had passed me by. I played Ufouria for the first time, and fell in love with somebody else’s childhood.

All of this is to say that the time was right to toss a new NES-style Mega Man game my way. What’s more, though, the time was right to toss a new NES-style Mega Man game the industry’s way. I wasn’t the only one rebuilding and reappraising the library of my childhood. Retro games were a hot commodity online and in stores. Services such as the Virtual Console allowed game companies to continue profiting from their back catalogues. And, most significantly, companies were releasing new titles that deliberately hearkened back to the roots of their respective series.

It was a bit of a fad for a while. Games such as New Super Mario Bros. (2005), Contra 4 (2007), Castelvania: The Adventure Rebirth (2009), Donkey Kong Country Returns (2010), Sonic the Hedgehog 4 (2010), Rayman Origins (2011), and others saw success and critical praise that proved that the kids who played those series hadn’t actually outgrown them…they rather fell away as the games drifted further from what they loved about them in the first place. The moment a popular franchise said, “We’re going back to basics,” ears pricked up.

Mega Man 9 rode that wave of revivals relatively early, meaning it felt both comfortable and fresh at the same time. Mega Man was back…and this time he wasn’t dragging along any clutter. Expectations were high, and Mega Man 9 managed to exceed every last one of them.

The game was and remains a masterpiece. And while I do enjoy nearly all of the games in the classic series, it was surprising and oddly fulfilling to suddenly have another Mega Man game that could be spoken of in the same breath as Mega Man 2 or Mega Man 3.

The fact that this arrived so long after the last Mega Man release was astounding. Even more incredible was the fact that several entire spinoff series came and went in the gap since Mega Man 8.

No, seriously. There was Mega Man Legends (1997-2000), Mega Man Battle Network (2001-2005), Mega Man Zero (2002-2005), and Mega Man ZX (2006-2007). If you want, you can also consider Mega Man X (1993-2004), which was largely released during classic Mega Man’s silence and Mega Man Star Force (2006-2008), whose final game arrived just a few months after Mega Man 9.

It didn’t just seem unlikely that Mega Man would ever return to its stripped-down origins; it seemed impossible. And remember…that previous paragraph isn’t a list of games. It’s a list of entire series. Mega Man had splintered and fragmented so many times over that there just wasn’t a place for the little boy in blue pajamas we had once loved so much. The climate wasn’t the same. Gamers had different expectations now. As Tom Petty once put it, everything changed…and then changed again.

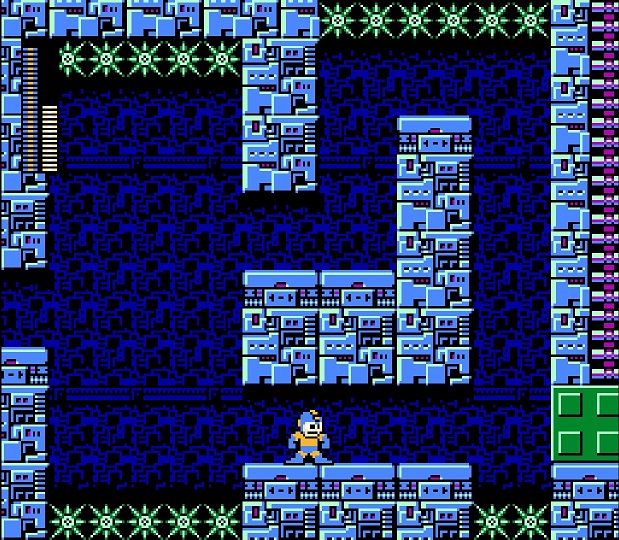

But Capcom brought Mega Man back. The original Mega Man. Without voice acting. Without convoluted mythology. Without extra fortresses and split groups of bosses and mid-point stages and gimmick levels. Without even a chargeable Mega Buster or the ability to slide. When many other series promised a return to their roots, they meant it in a general, spiritual sense. Mega Man meant it to the letter. If he couldn’t do it in the first game, he sure as hell wasn’t doing it here.

In truth, though, this game has less in common with the original Mega Man than it does with its celebrated sequel, Mega Man 2. The tighter physics, the richer sprites, the compositional philosophy behind the music, and the lack of a score system. This last, however, wasn’t so much missing as it was updated for modern sensibilities, but we’ll talk about that later. Mega Man 2 refined and defined the formula for the series, and Mega Man 9 ditched nearly everything that came afterward, and refused to roll the clock back any further.

Which is interesting, I think. Mega Man 9 feels to me like a proper sequel to Mega Man 2, and it’s a great one, finding a true swell of inspiration so many releases and years after most series would have lost steam for good.

It’s not unlikely that all of the credit for this belongs to Inti Creates, the developer who took on the seemingly impossible task of resuscitating a series that was both long dead and still revered. Mega Man 9, however it turned out, would have had to contend with unreasonable expectations across the board, and Inti Creates not only rose to the occasion…they arguably created the best game to bear the Mega Man name.

Of course, the company didn’t just swoop in out of nowhere. They’d worked closely with Capcom in the past, most notably by developing the entire Mega Man Zero series. For my money, Mega Man Zero is front to back the best Mega Man series. It’s certainly the most consistent in terms of quality, and it established Inti Creates as an important partner for Mega Man. The games were well received, each title successfully improved upon most of what came before, and it hearkened back to many of the best aspects of the Mega Man X and classic Mega Man series.

Capcom entrusted them with one of its coolest and most popular characters with the impossible task of relaunching Zero’s career after Capcom themselves sank it with the increasingly dire Mega Man X releases…and Inti Creates still hit a grand slam four times over. It’s really not surprising they were handed the keys to the classic Mega Man series later on.

Inti Creates’ true desires to work on classic Mega Man were probably most explicit in Mega Man ZX: Advent. That series was also great, and also belonged to Inti Creates. In Mega Man ZX: Advent, they included an unlockable mode that reimagined the game in the 8-bit style of the original Mega Man series.

It was a cute flourish far more than it was a statement of purpose, but it was also totally unnecessary. It required all new art and music. It required new AI and new physics. It was short, but it still placed the responsibility of building an entire framework from scratch on the plates of developers who already had another game to finish.

It was a labor of love. They did it because they wanted to do it. They wanted to build a game in the style of the NES classics.

I don’t know who initially pitched the idea for Mega Man 9, but, whoever it was, Capcom would have been positively idiotic not to give the job to Inti Creates.

While there’s very little design overlap between the Mega Man Zero series and Mega Man classic, I do think the quadrilogy of games Inti Creates built around Zero illustrated their ability to handle this throwback sequel. Mega Man Zero is a series that often demands and always rewards precision. It’s a series that expects you to die, and frequently, until you figure out the best way through a given stretch of a level. It’s a series that requires you to observe, understand, anticipate, and react to boss patterns. It’s a series made easier or more difficult by the sequence in which you choose to accomplish tasks. All of that should sound very familiar to classic Mega Man fans.

Most importantly, though, the Zero series proved that Inti Creates could be trusted to do work that was both respectful and innovative with established characters and mechanics. It may have been the first time Zero saw his name in lights, but players had been controlling him since Mega Man X 3, getting more familiar with — and excited about — his moveset with each subsequent game* in that series.

In short, though Mega Man Zero was technically the first game in a new series, it was also a successor to something players knew very well. Inti Creates didn’t have the luxury of building player expectations from scratch; they already existed, and anything they did would have to use the core of the original experience as its foundation.

They proved they could do it, four times over. (Six, if you count the related biometals in the Mega Man ZX series.) Controlling Zero was, if anything, even more of a tactile delight than it had been in the Mega Man X games. He felt faster in his own series, looser, and yet no less responsive. In keeping with the narrative of Mega Man Zero, it was as though he were reawakened, shook the stiffness from his joints, and became who he was meant to be all along.

What’s more, he felt at home, as the games were now designed around his flowing mobility, his graceful swordplay, his evolving movesets. Whereas games in the X series were built around what X himself could or couldn’t do and Zero was just an elaborate cameo, the Mega Man Zero games were playgrounds built exclusively for Zero. They not only lived up to the expectations earlier games had inspired in us, but they made us feel like these were the games we’d been waiting for all along.

I don’t want to dive too deeply into the Zero series** but I do think it’s helpful background information, and it explains why, after a long and what seemed like a permanent silence from the Mega Man classic series, Mega Man 9 landed out of nowhere with immediate perfection.

Okay, I say “out of nowhere,” but that wouldn’t be entirely true. In fact, I remember a trickle of buildup, which was surprising for a WiiWare*** game. WiiWare was a digital distribution platform that allowed large and small developers to release their games digitally on the Wii. Not all of the games were winners — not by a longshot — but there were a few pretty great ones. Usually, though, they just…appeared. Games were released weekly and you’d wait for word of mouth to direct you to standouts like World of Goo, Bit.Trip: Beat, Retro City Rampage, and the Art Style series. Hype came largely after the fact, as there were rarely demos or trailers to get players excited.

Mega Man 9 was different, though. I felt it coming. Like stormclouds in the distance, it was on its way, and I knew it. I was still mainly using my Wii to play old games — and I liked it that way — but now my interest was piqued for a new release.

Word spread that Capcom was releasing another Mega Man game…one that looked like the ones we remembered. The screenshots made that clear. It really did look very familiar, like screenshots from a title developed in the very early 1990s that was only now discovered in the archives. Then more information came along. The soundtrack would be NES-style as well. (Only we now called this “chiptune.”) And, so surprising to me that it felt like a decision born of glorious madness, there’d even be an option to let the game experience slowdown and flicker when too many sprites were on the screen at once.

This alone was a great joke; somebody actually took the time to program false system limitations into the game. After the entire video game industry had been pushing consoles as far as they could go on a regular basis, trying to squeeze that much more performance out of rigid system specs, Mega Man 9 built in an option to make it play intermittently like crap.

Because that’s how you remember Mega Man. And Mega Man 9 wants to be everything you remember about Mega Man.

Just the option for flicker — just the idea of the option for flicker — caused a long-dormant memory to surge back.

I remembered playing my original Nintendo and experiencing slowdown in a game I loved. It was possibly a Mega Man game. It was probably a Mario game. But the point is, I remember the action slowing down, frustratingly. I remember pressing harder on the buttons as though that would speed up my character’s animation. I remember expecting that at some point a more powerful version of the Nintendo would arrive, which would have enough processing power to run these games properly. I never felt as though the games were coded poorly, though they often were. I always felt that the Nintendo just wasn’t strong enough to let them run correctly.

Now, finally, I had an NES-style game to look forward to on a system that would let it run properly.

And the game was choosing to run like garbage.

I admire the sheer gumption of that choice to this day. I still laugh. I still love it.

For the first time since I was a kid, I got to look at a batch of upcoming Robot Masters and wonder which ones would be easiest, which ones to save for last, which ones would give you the best weapons. No, scrolling through screenshots wasn’t much like poring over an issue of Nintendo Power, but a little bit of that same thrill came back. Enough of it came back. And the nostalgia was helped along by the deliberately awful — and true to life — box art that Capcom whipped up. Another unnecessary gesture, as the game was only released digitally.

And so, while Mega Man 9 was technically of a piece with the other throwback-style games I listed above, it didn’t just want to recapture old magic…it wanted to transport you in time. It wanted to make you believe that this really was a game from the 8-bit era…just one, like Ufouria, you hadn’t gotten around to playing before. That “9” gave away its place in time, but very little else about the experience did.

The pixel art was beautiful, but it didn’t register as anything the NES wouldn’t have been theoretically capable of displaying. The soundtrack was the wall-to-wall best in the series, but it was also true to tunes we remembered and loved as children. The enemies, even the new ones, looked familiar. The weapons were better than we’d seen in any previous game, but they wouldn’t have felt out of place there. Instruments dropped out of the stage music to make way for sound effects — old and new — that were comfortable, natural, and familiar, right down to Mega Man sounding like a sneezing dog when he took damage again.

The stage layouts were all original**** while maintaining the design philosophy we passively internalized as children. You had a sense of when you’d experience the rise and fall of panic, you understood the precise degree by which the hazards would ratchet up in complexity, you encountered one enemy in a safe area and anticipated that that same enemy would be used differently later to threaten your life.

Words simply cannot express what a creative triumph Mega Man 9 really was. As if designed solely to prove that bigger is not always better, Mega Man retreated into simplicity and found the heart it had lost long ago. I fell in love with the game the moment I booted it up, and by now, hour for hour, it has to be one of my most-played games ever, right up there with Mega Man 2.

It was perfect, and I had no complaints.

I’m kidding, of course.

I had a complaint. It was hard as hell.

When I was using my Wii to replay the games of my youth, I, for whatever reason, hadn’t really bothered with Mega Man. I couldn’t possibly say why; I don’t think it was conscious. I think, more likely, I had just not gotten around to it yet. Mega Man 9 was the first time I’d played any Mega Man game in ages.

And I died.

A lot.

And frequently.

More than you could even imagine.

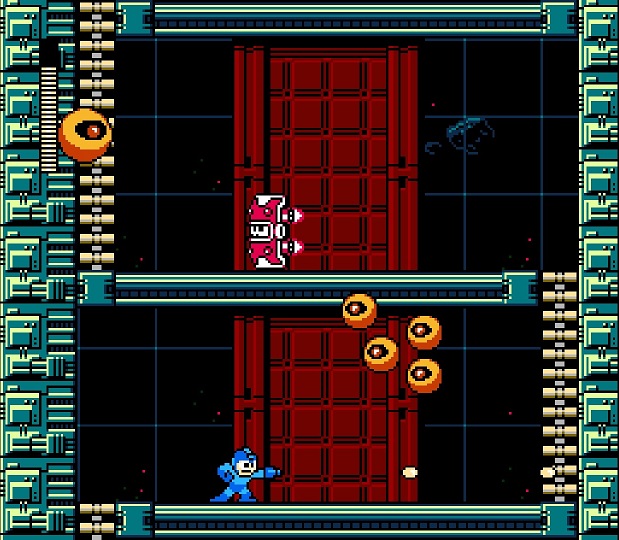

Every screen was difficult. No stage seemed notably easier or harder than any of the others. Usually in a Mega Man game you’ll hop from level to level until you find the one nut that’s easiest to crack. Typically the boss of that level is also a relative pushover, but even if he’s not you can at least reliably clear the stage and take pop after pop at the champ.

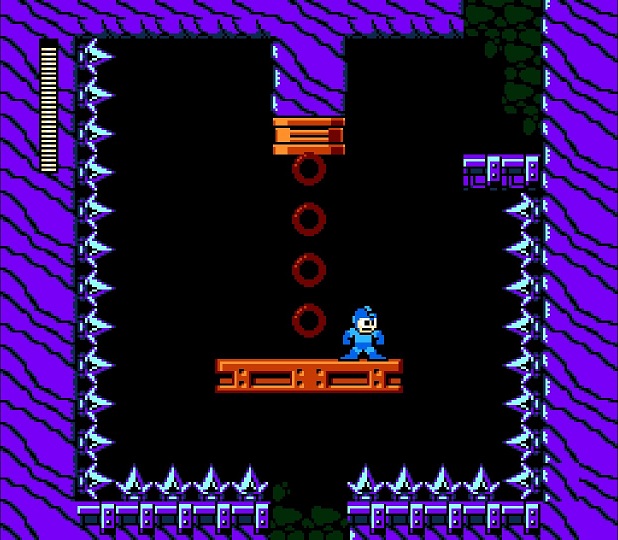

In Mega Man 9, though, nothing was easy. The enemies whittled my health down quickly. I’d limp from screen to screen, hoping to make it just a little further. (And rarely succeeding.) As if to mock me, the game would finally drop health or extra lives for me…into pits and onto beds of spikes. When I managed to figure out how to deal with an enemy or a particular configuration of enemies, some other obstacle would then serve as a brick wall against my progressing any further.

It was rough. It was cruel. It was relentless.

And yet…I kept playing.

Just like the Mega Man games of my youth.

The truest Mega Man 9 comes to the series isn’t in its optional flicker or its period-appropriate box art. It’s in the compulsive need it inspires in you to keep beating your head against that wall. I’ve played plenty of games that stand imposingly before me and knock me down every time I try to stand back up. Nearly all of those see me giving up at some point, and letting the game exist without me. Very rarely do I do what I did with Mega Man 9, and a number of its predecessors, which is surrender myself to it, let it kick my ass repeatedly, and finally learn to outwit it.

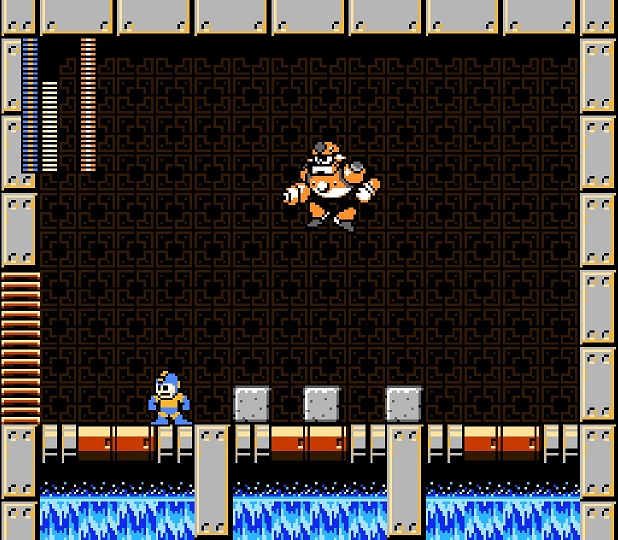

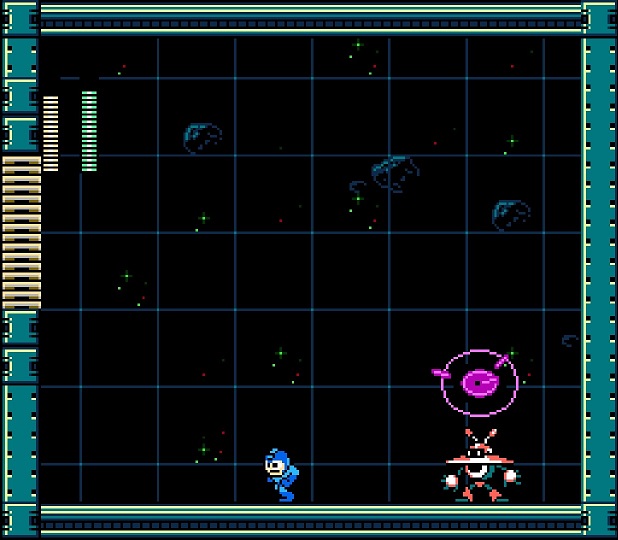

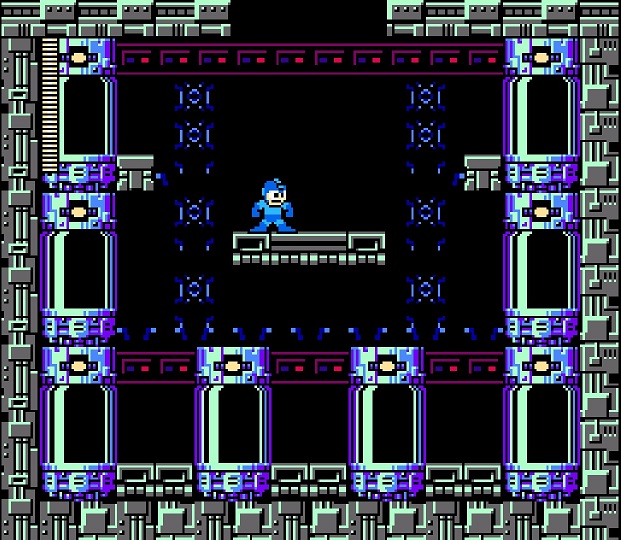

I came a long way with Mega Man 9. A game that seemed comically impossible gradually gave way to a rewarding adventure that just required vigilance. It wasn’t nearly as unfair as it had seemed at first. I remember struggling for days to take down any of the Robot Masters, only to finally force my way through the battle with Galaxy Man. But fast forward a few months and there I was, performing a live playthrough of the entire game for viewers on a stream. Not only could I now reliably beat it, but I could do so in one sitting, in front of an audience. I remember one commenter saying he had never seen anyone take down Dr. Wily as fast as I did.

The game I could barely play became one I was actually, legitimately good at.

Actually, no; strike that. The game made me good at it.

It trained me. It enabled me. It tore me down and dared me to try again, but each time I did I learned a little more about what not to do. And then a little more about what to do. And then a little more about what I could do better, or faster, or more impressively.

Mega Man 9 isn’t easy, but if you’re willing to spar with it, you’ll come out so much stronger for having done so. It has a sturdy, sometimes cold internal logic that you need to learn how to read. It plays by rules…just not your rules. And it leaves itself open just enough that you keep coming back…after you get the profanities out of your system and pick the controller back up.

I don’t mean to suggest that the game is entirely fair. Replaying it now — so long after I’ve come to grips with its quirks — there are still a number of moments that exist only to be troublesome.

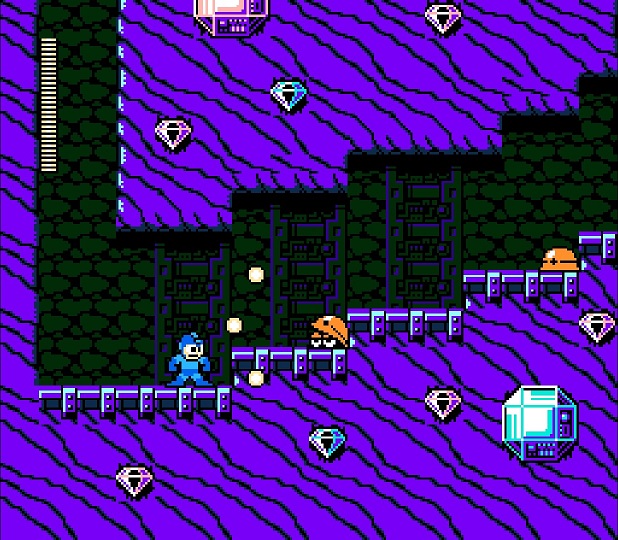

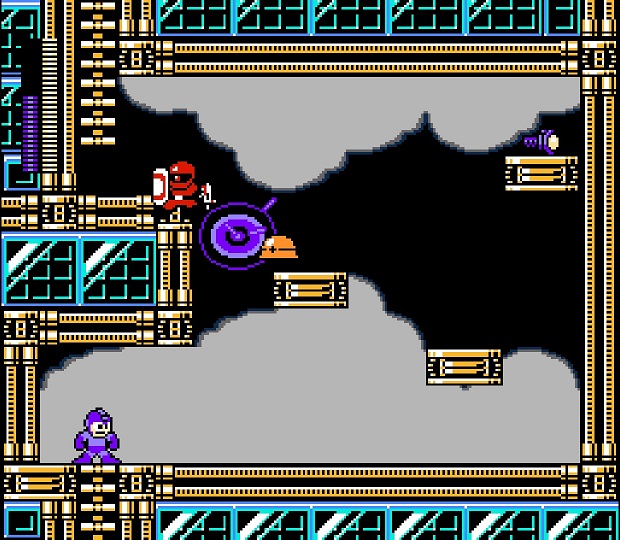

There are the little grabber enemies that rush you into death spikes in Galaxy Man’s stage and Wily’s fortress, which are almost uniformly impossible to predict your first time through. There are the draining water platforms in Splash Woman’s stage that require you to navigate them while they move at different speeds around death spikes. There’s the swing in Jewel Man’s stage above a bottomless pit and next to a wall lined with death spikes, requiring you to jump toward both and hit the gate rather than either of the two hazards.

You know, I’m noticing a pattern here…

Yes, one of the recurring criticisms is that Mega Man 9 is a bit too liberal with its use of death spikes. The entire time I’ve been replaying the Mega Man classic series, I was prepared to get to this entry and dispel the accusation. “Mega Man games were always full of death spikes,” I’d say. “This one just seems to have more because you played it more recently and haven’t spent as much time memorizing how to handle them.”

But, well, I’ve just recently replayed the previous eight games…and I can say with confidence that the critics are correct. Mega Man 9 is a bit too liberal with its death spikes.

We’ve talked before about the health bar functioning as a kind of ticker that represents the number of mistakes you can make before the game shoots you back to a checkpoint. And I think it’s helpful to view it that way; Mega Man encourages perfection. If you like, you can take risks and hope for the best, but you can only do that a finite number of times before you lose too many of the bets you place.

Mega Man games don’t let you coast on luck, because you’ll never be lucky enough times in a row to finish the game. You can afford to tank your way through certain obstacles, but you’d better learn the rest, because you’ll never make it to the boss doors otherwise.

Mega Man 9‘s overuse of death spikes, though, betrays that mutual understanding. You don’t get to learn by making a mistake and moving on, crippled by your error. Your error far too often kills you, and you’re back to the checkpoint. Often you won’t even know what you were supposed to do differently. That’s a feeling that really sets in during the fortress levels, which have a bit more personality than they had in previous games, but are only marginally more fun than they ever were.

It’s a bit difficult to put myself back in the shoes of a new player. When I play through Tornado Man’s rainy sections, I know there are platforms behind the clouds to make platforming easier. When I’m launched skyward by Galaxy Man’s teleporters, I know the flying enemies will never hit me as long as I don’t panic. I know which way to veer during screen transitions to keep from clipping a spike with my foot and exploding unglamorously.

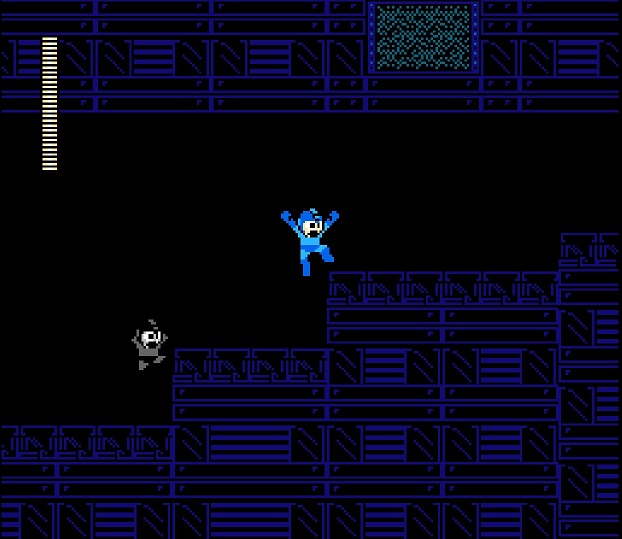

Back then, though…I remember experiencing a mix of emotions. At first — nearly always — I’d laugh. Some unforeseeable hazard swooped in and killed me. Ha ha.

It seemed almost knowing…a wink to the player. “Remember when games used to be this cruel?” And it was a good joke. The death was worth the chuckle.

For a while.

Because it would happen again and again throughout the course of a level. It would strip me of my lives, one after another. It would frustrate me so much that I’d get careless, and die even more than I was already fated to. The joke got old. An instant-kill hazard I have no way of knowing how to navigate appears three quarters of the way through the level, and I’m on my last life. I die, as I must, learning nothing about how to progress, and am booted back to the stage select.

Repeat. Over and over and over again. All I wanted to do was make it to the boss so I could see if I had the right weapon, and maybe get a sense of what to expect when I fought him (or her!) properly. But I’d make it to the boss so rarely, and when I did I’d have so little health remaining. I’d be killed by the first attack and kicked out of the stage knowing no more than I did when I started.

My girlfriend at the time watched me play. She watched me die. She heard me shout, “No!” more times in an hour than I’m sure she thought was reasonable. At one point, I asked her if she wanted to try. She declined. “I don’t know why anybody would play a game that punishes them like that.”

She…had a point.

Granted, I think she was at the other end of the spectrum. The games I knew she liked were Animal Crossing, and whichever Katamari game it was that asked you to collect one million roses. Not that I disliked those games, but watching her play those was such a foreign experience to me. She steered little avatars around environments that couldn’t hurt her, let alone kill her. Everything was sunny and welcoming. Reflexes and experience barely even entered into it.

I don’t mean to imply that those games are or were in any way beneath me — I now enjoy both series on their many merits — but when I sit down to play something, I rarely reach for a game that requires so little of me.

Instead, she watched me reach for a game that requires everything of me, and then spits in my face and tells me that I’ll never be good enough. Surely an ideal — and emotionally healthy — gaming experience lay on the spectrum somewhere between those two extremes.

But I kept at it. It punished me, she was right, but it never defeated me. First Galaxy Man. Then Splash Woman. I think it was Tornado Man next, but I know for a fact that Plug Man was last. Piece by piece, I chipped away at that wall. And then I finally made it to the Wily fortress, which made me chuckle with its eyebrow waggling introduction and then promptly beat the living shit out of me over and over again.

And yet, I was still making progress. Even when I wasn’t doing anything but entering a stage and dying to the same enemy or obstacle over and over again. And that’s because of one great carryover from Mega Man 7: the shop.

Or, I suppose, more specifically the currency. Bolts were back, and you could trade them in for all kinds of helpful items, from familiar (and invaluable) ones like 1-ups and E-tanks to gracious additions like the one-off ability to negate death spikes. And that’s where the feeling of progress comes even when you’re not earning new weapons or scratching Robot Masters off your hit list.

I read a book recently about the development of the excellent Rogue Legacy. I won’t bother looking up the title, because the book wasn’t very good. But one of the game’s designers spoke for a while about how the leveling system in that game allowed players to feel like they were advancing, even if they kept failing in the same area each time. Their characters would get stronger, they could upgrade their equipment, they could discover new, permanent items in chests…basically the design of the game kept players from feeling like any given run was fruitless, even if they didn’t make it any further than they had previously.

Mega Man 9 offers something similar. You can keep dying, sure, and you will. But you’ll also be accumulating bolts as you do, and those carry over. Die enough and, yes, you’ll be frustrated, but you’ll also have a cache of cash that you can use to invest in items that will give you an edge. You can load up on lives and health restoratives to your heart’s content. In an apt metaphor for so much, failing really could make you stronger.

It was a smart design move, and a further reinforcement of the fact that the limited currency of Mega Man 8 was a bad idea. The shop needs to function as an ongoing reward, whereas Mega Man 8 turned it into an additional source of stress as you could never buy all the upgrades, meaning each purchase locked you permanently out of the chance to buy something else.

The shop did almost have one thing in common with Mega Man 8, though; while the stripped-down jump-and-shoot moveset of the original Mega Man was known long in advance to be the approach Mega Man 9 would take, there evidently were plans for the shop to sell permanent upgrades in the form of sliding and charging the Buster.

This I do think would have represented a nice middleground; those who struggled could buy the upgrades for an easier run through the game, and purists could ignore them. But I believe Inti Creates made the right decision by scrapping the idea. Nobody in their right mind would have avoided grinding for the bolts necessary to purchase those upgrades, and therefore the core Mega Man moveset would have been relegated to the opening stage or so, before players could afford to move on from it.

By removing the option altogether, Inti Creates forced everybody to familiarize themselves with the same limitations, and to engage the game without those additional offensive and evasive capabilities.

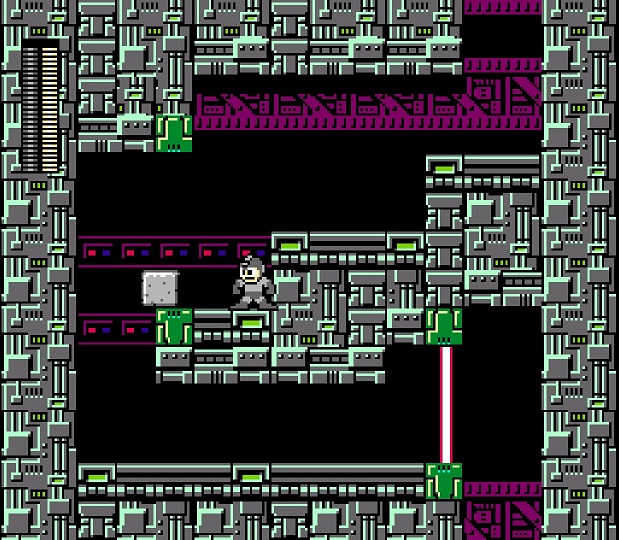

Mega Man 9 did offer somewhat of a concession there, however. It was the first game in the series to make DLC available, and one of those options was the ability to play as Proto Man for the first time ever.

This version of Proto Man could slide and charge his Buster, much like Mega Man could in Mega Man 4. But that wasn’t all; he also had a shield that deflected projectiles (so long as you were in the air and not firing).

All of which makes it sound as though Proto Man’s run of the game would be far easier…except that there were some artful tradeoffs.***** Proto Man didn’t have access to the shop, he took double damage, he had more significant knockback from enemy attacks, and he could only fire two Buster shots at a time, compared to Mega Man’s three. Then again, playing as Proto Man meant you got to hear his iconic whistle at the start of every stage, so maybe it was worth it.

Playing as Proto Man was a great bonus, but the mode removed all of the story sequences and felt more like a novelty…a more punishing sprite-swap than anything else. I have to admit that this is something Mega Man 10 did far better than this game.

There were other bits of DLC available as well, including harder difficulty settings, a fairly dull extra stage with another boss (something else Mega Man 10 did far better, as we’ll see), and my personal favorite: Endless Mode.

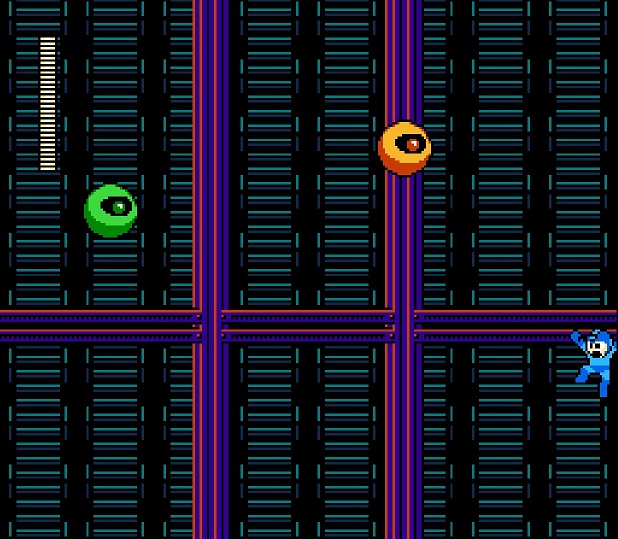

Endless Mode was almost as good as the game itself, and (living up to its name) was endlessly replayable. The mode would hand you all of the special weapons in the game and toss you into a randomized series of corridors. Every 30 or so screens you’d have to face a Robot Master.

It was that simple, but it was extremely addictive, and it’s one of the highlights of the entire series to me. Sometimes I wouldn’t make it further than a screen or two. Just once (if memory serves) did I make it beyond 100 screens, and when I did I was sweating and tense.

Endless Mode was, essentially, the chance to play new Mega Man content whenever you wanted to. And while you could devote enough of your life to it that you catalogued and memorized all of its surprises, there was more than enough content there to keep most players happy for a very long time. (Mega Man 10‘s equivalent mode wasn’t nearly as good, however, and felt as though it contained significantly fewer modules.) It also made a scoring feature — not seen since the original Mega Man — feel meaningful. Nobody cared about beating their high score in that game…but getting further in Endless Mode than you ever had before? Now that felt good.

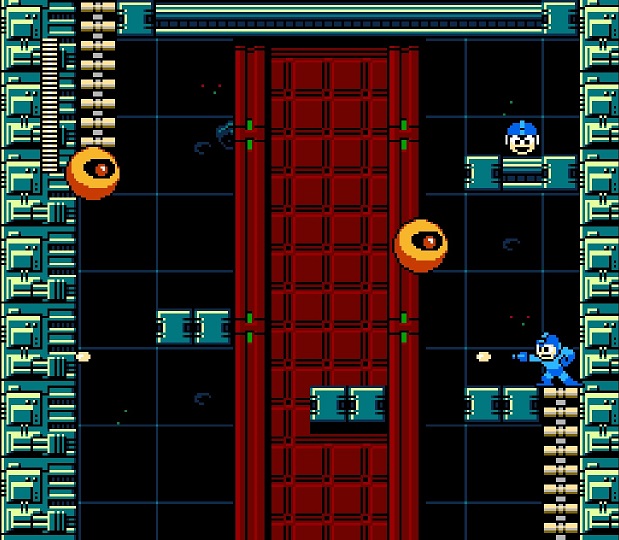

And, so, yes, that’s a lot of gushing. But we haven’t even started praising the single best set of weapons in Mega Man history.

As you’ll recall, I was very happy with Mega Man 7‘s loadout overall. In fact, I honestly couldn’t ask for anything more. And yet, Mega Man 9 gives us so much more.

In previous installments I’ve voiced my disappointment that the weapons felt as though they were designed in isolation from the stages. They were fun things for Mega Man to hurl around the screen, sure, but they didn’t feel tailored to the games themselves. They felt, at best, as though they’d been plugged in after the fact, and at worst as though they were just differently shaped projectiles for the sake of fulfilling a quota.

You’d be forgiven for assuming that with (at least) eight new weapons introduced in every game, the well had simply run dry. There was no real way to design a truly great arsenal of original weapons anymore. And I would have agreed. Mega Man 9 gleefully proves us wrong.

The weapons here are not only fun, but they’re useful. They’re versatile. They’re worth playing with, even when you don’t “need” them. And, most impressively of all, nearly all of them of them also function as utilities, meaning poor, overtaxed Rush can revert back to his basic Coil and Jet functions.

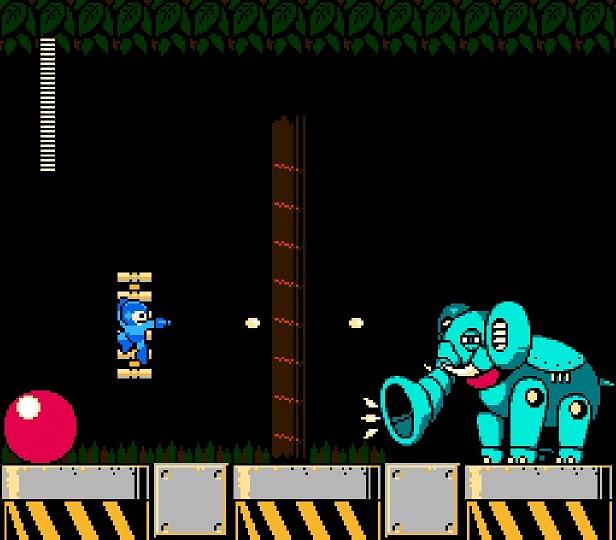

The simplest of the new weapons is probably the Plug Ball. It’s a cross between the Spark Shock and the Search Snake, but with an actual purpose. The Plug Ball drops directly to the ground and runs forward, around platforms, across the ceiling, and pretty much anywhere else it can get without crossing gaps. It’s powerful and fast, which in many games would earn it a spot among the best weapons. Here, it gets outdone by everything else, and that’s a great thing.

Next there’s the Jewel Satellite, which is even better than the Junk Shield, but feels more specifically like an upgraded version of the Leaf Shield or Star Crash. Four jewels orbit Mega Man and will take out weak enemies easily, only breaking if they hit an enemy powerful enough to withstand them. (This actually makes it superior to Jewel Man’s own version of the weapon, as his Jewel Shield chips away each time it’s struck by a Buster shot.) You can throw it when you’re done using it, but you can also move while it’s active, which makes it extremely handy in nearly all of the game’s long gauntlets.

The last of the “standard” weapons is the Magma Bazooka, an enhanced version of the Atomic Fire. It’s chargeable, like its forebear, but it launches three projectiles instead of just one, making it a decent spread weapon.

The rest of Mega Man 9‘s arsenal is truly great, though.

The Concrete Shot deals a decent amount of damage, but its main selling point is the fact that it creates temporary blocks to stand on. This is a huge asset when it comes to many of the game’s tricky platforming challenges; it’s not easy to aim the Concrete Shot precisely, but the odds are good you’ll get it close enough to create a foothold somewhere helpful. You can also use it to climb higher than you normally would, as well as block lasers late in the game and solidify the lava blasts in Magma Man’s stage and the fortress.

The Laser Trident is super fun, and a great example of doing the “differently shaped projectile” right. Not only is it powerful, but it’s ammo efficient. What’s more, it flashes and makes a really cool sound…and since this is a video game, flashing and making a cool sound is a legitimate selling point. Additionally, it pierces armor, and will sail straight through rows of enemies. What’s more, this is Mega Man 9‘s weapon for tearing down certain barricades, which makes it worth grabbing early so that you can reach items that are otherwise blocked off. It can also destroy the lava blasts you’ve hardened with the Concrete Shot. It gets a lot of use.

Then there’s the Tornado Blow, which is a retooled Gravity Hold that wisely doubles as an assist to Mega Man’s jump height. Trigger it at the right time and you’ll get a lot of extra lift on your ascent, which is a pretty cool feature. It also adjusts some of the platform heights in the fortress. The Hornet Chaser is the game’s homing weapon, and the fact that it actually works makes it a very rare thing indeed. What’s more, the hornets will seek out and collect items for Mega Man, many of which can’t actually be obtained in any other way. Do you really want that large health that fell into the death spikes? Sure you do. Hornet, chase ‘er. (Aaaand just like that, I get the joke behind Splash Woman’s weakness.)

The best of the batch is the Black Hole Bomb. This one is powerful, steerable, and triggerable at will. You can feed it into almost any area of the screen, detonate it, and watch as enemies and projectiles are drawn into it and erased from existence. Do it above yourself and get ready to be showered by the falling health and ammo of your swallowed foes. The Black Hole Bomb consumes a lot of ammunition, but the sheer value of the item absolutely justifies the lack of efficiency, and it’s one of my favorite weapons in the entire series.

The special weapons prove that Inti Creates did its homework. They looked back at previous weapons, determined what made them fun to use, and ensured that they were woven into the gameplay experience itself. For once, you didn’t just pull a weapon out because it would deal more damage to a certain enemy; you pulled a weapon out because it was the best answer to the puzzle posed by a given room.

Mega Man 9 is so slickly designed and perfectly presented that it retroactively makes the best things about the previous games in the series look like happy accidents rather than deliberate choices. Sure, the other Mega Man games were largely great, but never had they felt so deliberate. Here, every gear feels perfectly placed and finely tuned. It’s a deceptively complex machine that improves upon the stacks of blueprints that inspired it. It’s a game that must have been subject to endless playtesting, because as cruel as some of the sequences can be, especially to new players, everything feels right.

It seems as though Inti Creates took the same approach to the stages as they took to the weapons…replaying them all, parceling out moments that worked and moments that didn’t, and reverse engineering the entire Mega Man experience to find out what really mattered underneath all of the clutter.

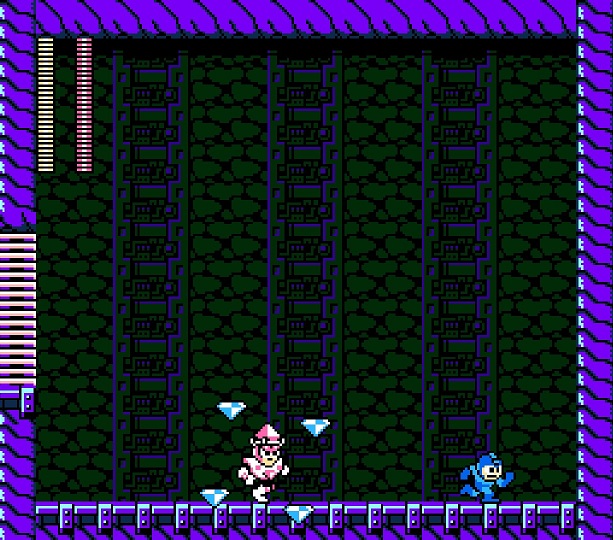

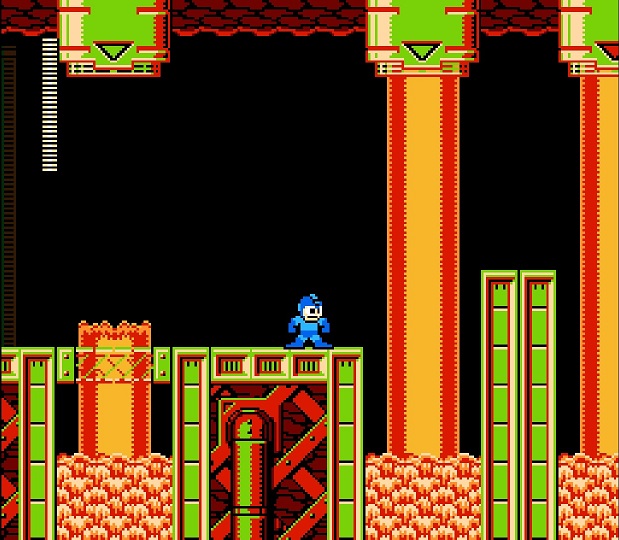

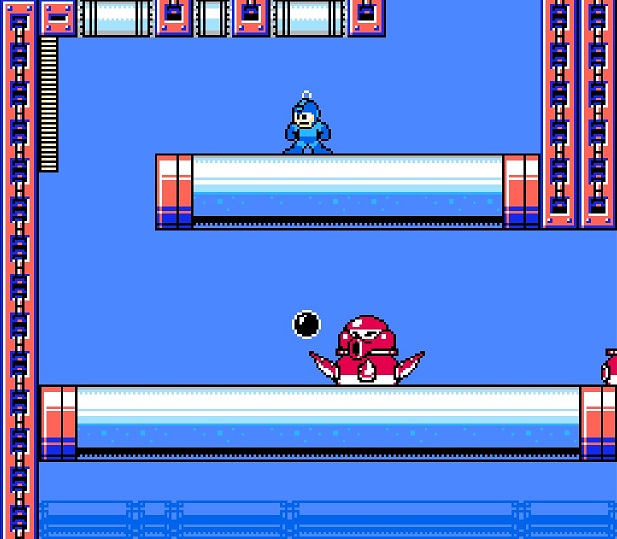

And it worked. In addition to offering my favorite batch of weapons, Mega Man 9 may also offer my favorite batch of stages. Some of them are fairly basic Mega Man fare, but Splash Woman’s stage is one of the better and more varied water stages in the series. It has a variety of interesting enemies, each of which requires a unique approach. The octopus enemies have to be coaxed out of their pots, the mines force you into a brief and hectic dance, and the fish that torpedo you from the sides of the screen require you to be constantly ready on the trigger. The death spikes here aren’t even too bad, as the water physics are almost always present, giving you more maneuverability and allowing you think at a more reasonable pace.

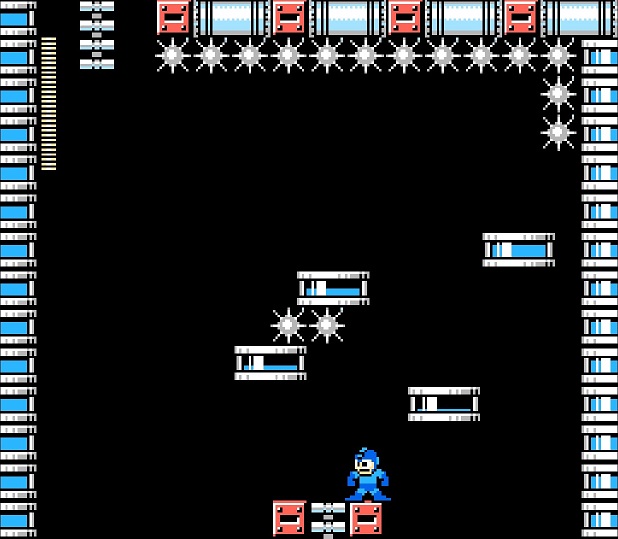

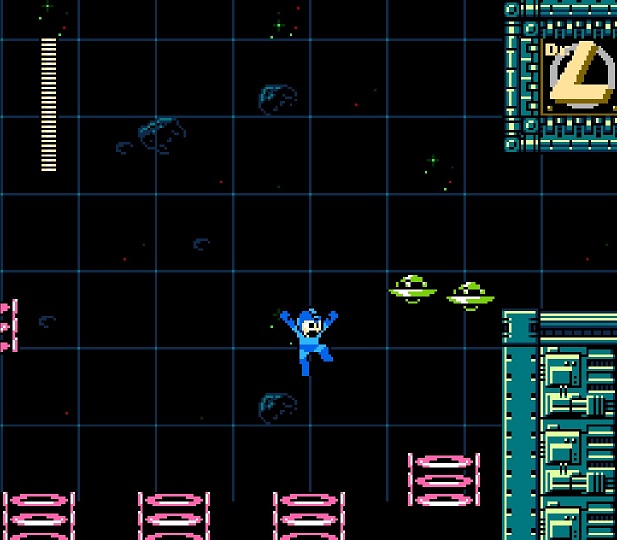

Galaxy Man’s stage is probably my favorite, for sheer flair alone, with the teleporters being a fun little mechanic and the 8-bit futuristic aesthetic being exactly the sort of environment I would have fallen in love with as a kid. Hornet Man’s garden-themed stage is a nice, unexpected approach, and Magma Man’s stage does the impossible and makes a fire level more fun than frustrating to play.

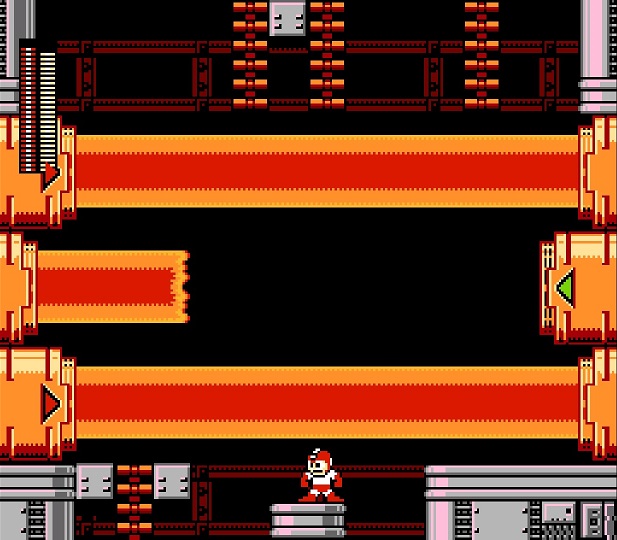

For sheer variety, though, I think Tornado Man’s stage is the most impressive. It has spinning magnetic platforms which are used in multiple ways and can be handled in multiple ways, but it also leans into the weather theme more than we’ve ever seen the series do before. It opens with a clear, sunny stretch to help you get acquainted with the enemies and magnets, but then you’re working against the wind while stormclouds obscure hazards and platforms alike. Then you’re navigating a frozen area with slippery ice physics. And then you’re flying forward with the wind at your back, forcing you once again to come to terms with movement and momentum in a whole new way. It’s a really great stage, and an easy standout.

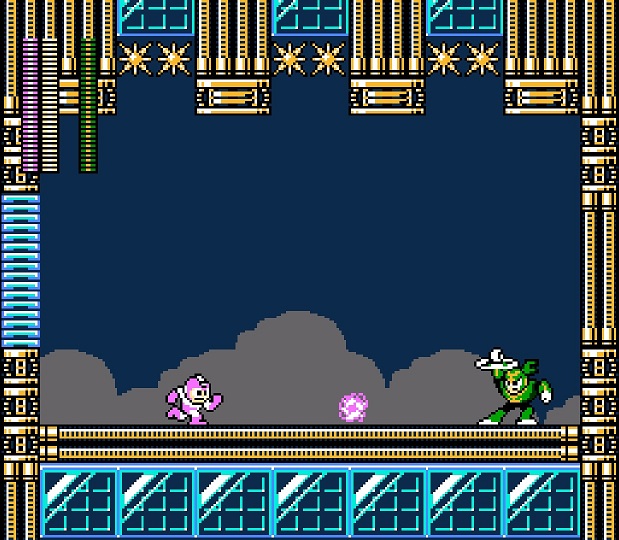

The Robot Master duels themselves are also a lot of fun and rewarding to figure out, with most of them requiring you to pay attention to more than just the boss and his (or her!) direct attacks.

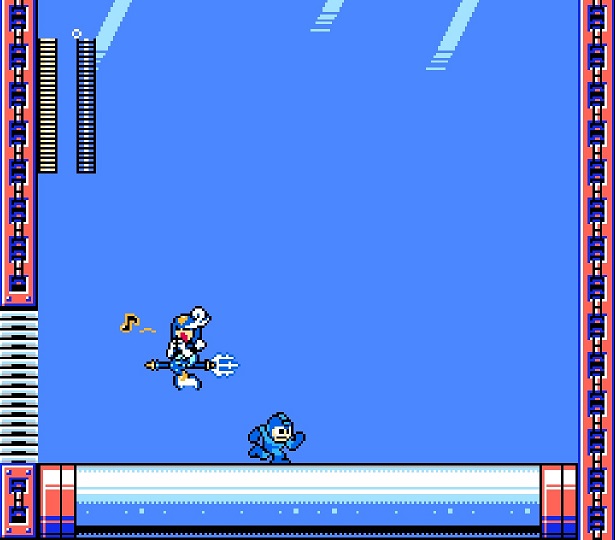

Splash Woman asks you to watch for her Laser Trident from above and fish from the side. Jewel Man’s shield fragments fire back at you any time your shot connects with them. Tornado Man’s fight may actually be the best, as your location dictates where his Tornado Blow will appear. (Tornado Man’s design also hearkens back — and narratively forward — to the design of Harpuia, a recurring character from the Mega Man Zero series, which is some efficient continuity.)

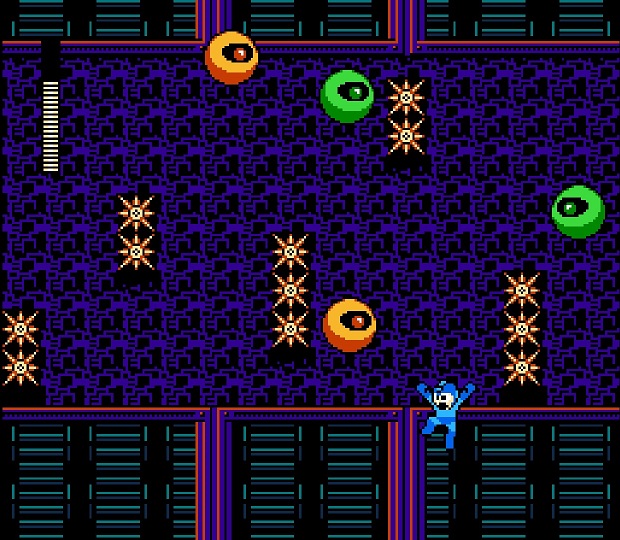

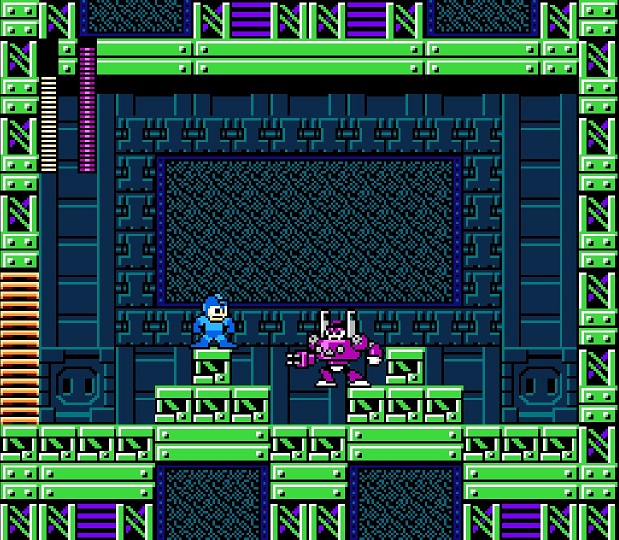

I think the only duel I really don’t like is the one with Plug Man. It feels as though there’s just a bit too much to keep track of there, with multiple Plug Balls zooming around the screen and dropping from above, while Plug Man himself hops around unpredictably. Electricity-based Robot Masters tend to be among the most annoying, and this one doesn’t break the tradition. It’s the only fight I think is too busy, and the only one I still haven’t been able to complete Buster-only without taking damage.

The soundtrack does a lot of the work toward making the levels feel as great as they do, without a single weak track in the game. Jewel Man and Plug Man have probably my two least favorites, but they’re still great. Hornet Man’s is a bouncy, flighty tune that I always find myself enjoying more than I expect to. Concrete Man’s is a hard-edged homage to Wood Man’s theme, the first industrial forest level in the series. Tornado Man’s is a swirling, pulse-pounding masterpiece that fits perfectly with every weather condition his stage throws at you.

Splash Woman’s theme is beautiful, buoyant, and blue, and it ranks high on my list of all-time favorites. Magma Man’s is my favorite fire theme in the series, with a raging composition that evokes fiddles and brass intermittently and makes the entire area feel far more playful than it rightly should.

But Galaxy Man’s? Oh. Oh, Galaxy Man’s…

That song is a masterpiece. It’s the best track in a game full of standouts, and I’m sorry that the stage it underscores is the easiest, because that means I get to hear it that much less frequently. It’s almost too good, with it sometimes distracting me from the action on screen and causing me to make foolish mistakes. I love it, and there’s not a single track in Mega Man history that I’d rank higher.

I do have one complaint about the soundtrack, though: all of the stage themes sound like they could be Dr. Wily themes.

I don’t have the vocabulary to explain why, but if you think back to other strong themes from the previous games (Elec Man, Bubble Man, Snake Man, and so on), they feel tailored to their levels. You couldn’t play any of them underneath a Wily fortress stage, because it wouldn’t feel right. They were written for one particular area, and couldn’t survive in another.

In Mega Man 9, though, every stage’s theme sounds like a potential fortress theme. Thumping. Excitable. Drawing you forward. And while that’s by no means a bad thing, I find it a bit odd. It’s as though Mega Man 9 is full of fortress music as opposed to Robot Master music. Great compositions, but often they feel less tied to the identities of their levels.

That’s truly reaching for a complaint, though. And while I ladled out some disappointment above, if you can move past those rough edges — and many people were certainly able to — you have the best Mega Man game in ages. Possibly even the best ever.

I’ve gone back and forth — and even as I write this sentence I continue to go back and forth — about whether or not I prefer this to Mega Man 2. In my mind, Mega Man 2 is my easy favorite. But playing them again, reappraising them so close in time to each other, I’m not as sure.

Mega Man 2 has its ropey moments, as we’ve discussed. Mega Man 9 irons nearly all of them out. Sure, it introduces one or two of its own, but it also has better stages, on the whole. It has a better fortress. It has better weapons. It even, incredibly, has better music.

So I really don’t know. In a way, it doesn’t matter. I can pick either one today and change my mind tomorrow. And the mere fact that I can ask myself this question speaks volumes about just how successful Mega Man 9 really was about what it set out to do.

According to the old saying, you can never go home again. Mega Man 9 heard that and replied, “Like hell you can’t.” It provided a genuinely great — and remarkably true — retreat to a time when, for many players today, games actually meant something. When they were hard as hell and you’d stay up all night passing a controller back and forth just to make it one stage further. When you gathered around the TV to cheer and howl with dismay whenever something incredible happened on the screen.

I shouldn’t have been transported there. I was too old. I was too far along in my life. Video games didn’t mean the same thing to me that they meant then.

But Mega Man 9 took me by the hand and led me there anyway. It led many people there. And we found each other. Maybe this time it was online, sharing stories and tips and videos, beating the game during a live stream for others who had never seen the ending, comparing high scores in Endless Mode or showing off the achievement we’ve earned…including that incredibly rare and maniacal one that requires you to beat the game without taking any damage. Hell, my review of Mega Man 9 for a site I used to work for is what inspired Nintendo Life to reach out and hire me. The game singlehandedly turned me into a professional critic.

It was perfect, and part of me wishes the series ended forever, right here, on a note higher than any of us had any right to expect of it. What’s more, it would have left us with three trilogies, forming a perfect three-act structure. In the first three games, the young hero finds his footing. In the next three, he slowly loses his way and credibility, but not his drive. In the final three he struggles through a crisis of identity to find and redeem himself.

I know the phrase gets thrown around a lot, so forgive me for bumping the ball back into the air, but there really is no better way to put it: Mega Man 9 was what you thought you remembered of Mega Man, but it provided a better, more careful, more meticulous experience than Mega Man actually was. It was also self-aware to the point it had a number of genuinely good jokes sprinkled throughout, in particular the montage of Wily begging for his life.

Inti Creates was having fun. And why not? If gamers got to revisit and rediscover the games of their youth, developers had every right to enjoy the same opportunity.

So, okay. I’ve danced around the question enough. Was it better than Mega Man 2?

I don’t know.

And, again, it doesn’t matter.

But I think I’m going to give Mega Man 2 the edge. Not because Mega Man 9 isn’t, strictly speaking and removed from nostalgia, the superior experience. But rather because it means one thing to set the standard for the entire series, and something else to live up to it.

I’ll pay my respects to the pioneer, because his successors wouldn’t be here without him.

Best Robot Master: Splash Woman

Best Stage: Tornado Man

Best Weapon: Black Hole Bomb

Best Theme: Galaxy Man

Overall Ranking: 2 > 9 > 7 > 5 > 4 > 3 > 1 > 6 > 8

—–

* The games themselves fluctuated wildly in terms of quality, but I think it’s safe to say that playing as Zero remained a fairly consistent highlight.

** Would there be any interest in a Mega Man Zero retrospective done in this style? With only four games it would be fairly easy, but I also have no clue who would or wouldn’t want to read it.

*** It was also released on the PlayStation Network and Xbox Live, making this the first Mega Man game to be multiplatform on release, but I played the WiiWare version, so that’s my point of reference. I’m unaware of any meaningful difference between the three releases, but please let me know if you can report any.

**** The main exception is the stretch of Splash Woman’s stage that borrows the bubble ride from Wave Man, but there are also some fun recreations of previous game levels parceled out in Endless Mode.

***** There’s also the fact that Proto Man’s Buster is lower to the ground, but I couldn’t decide if I should list that as a positive or negative attribute. I’d say there are an equal number of ticks in both columns, so I’d consider it a wash.