Welcome back to Trilogy of Terror, a series in which I take an in-depth look at three related horror films in the run-up to Halloween. This is the first installment in this year’s trilogy; the second will go live October 24, and the third on Halloween itself.

The films I feature in Trilogy of Terror could be films in the same series, films by the same director, films with a common theme, or films with any relationship, really. This year’s theme is “The Most Dangerous Games,” movies about competitions whose outcomes mean the difference between life and death.

As a bonus entry this year, I took at look at the page-to-screen adaptation of The Running Man. You may want to read that before continuing into this review, as it served as an unexpectedly great point of comparison.

Once I decided to cover games of life and death, The Running Man came immediately to mind. I didn’t realize at that point, however, that in the exact same year, another, much smaller film was released that handled the same premise far better.

Deathrow Gameshow is actually fun. Not great, and I probably wouldn’t push back too hard if you told me it wasn’t even good, but it sure as hell approached its premise creatively and with an infectious giddiness. The Running Man was too busy letting Arnold Schwarzenegger disembowel his pursuers and his dialogue too have any fun. Deathrow Gameshow can’t imagine doing a movie like this and not having fun.

It’s a silly comedy that may have something to say about the media, desensitization, celebrity, and God knows what else, but a cheap laugh is still a laugh and it will gladly stoop to one at any time.

The premises in the two films are remarkably similar, and certainly coincidental. The fact that they were released in the same year means writer and director Mark Pirro happened to come up with Deathrow Gameshow in a case of parallel invention.

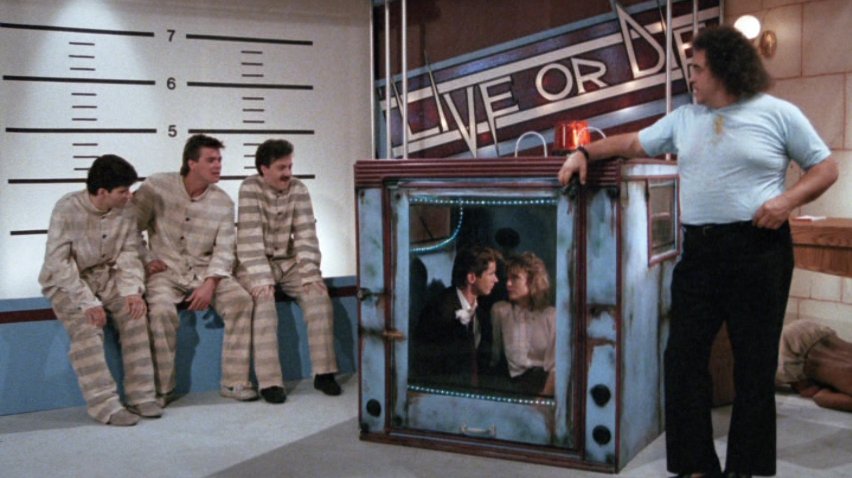

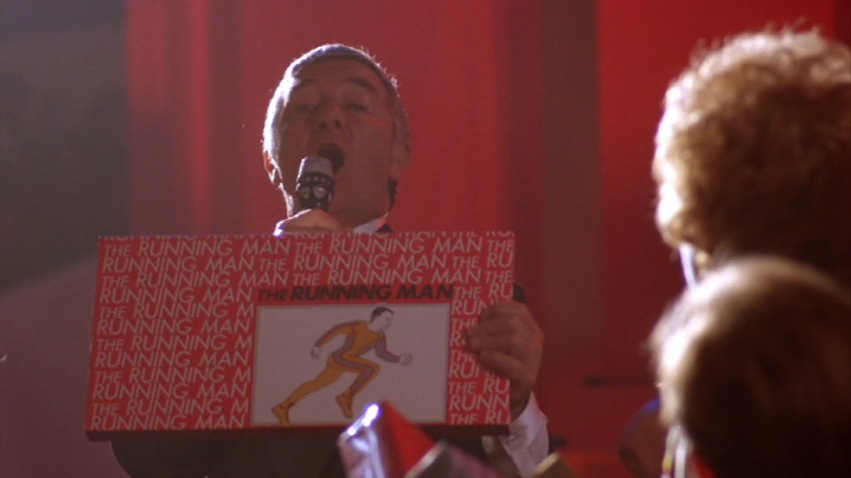

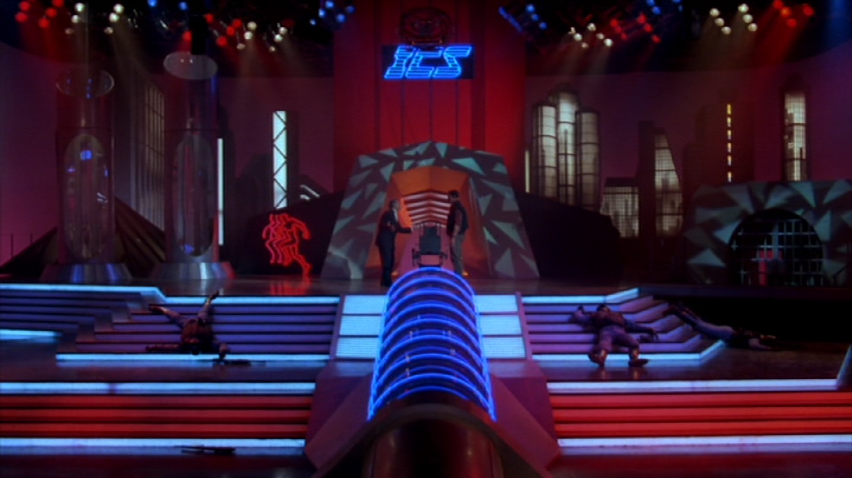

Deathrow Gameshow, just like The Running Man, focuses on a popular game show in which convicted criminals risk their lives for a chance at freedom.

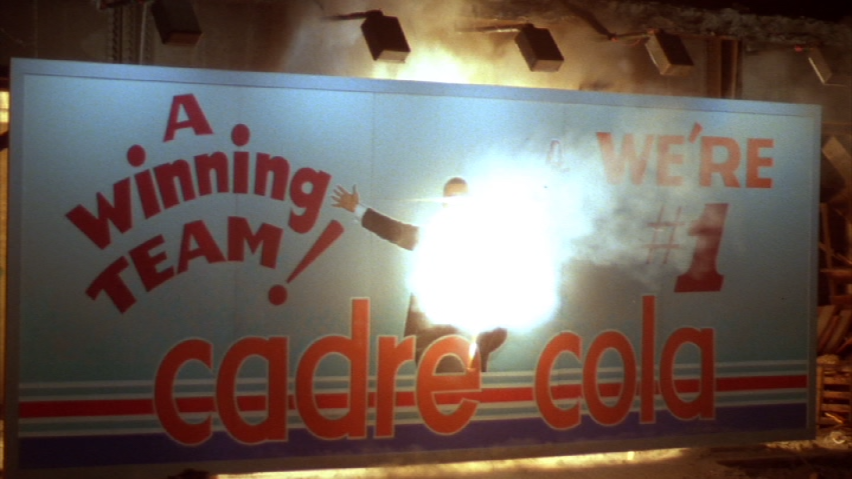

Here, that show is called Live or Die, and it combines familiar elements from Let’s Make a Deal, The Price is Right, Double Dare, and more.

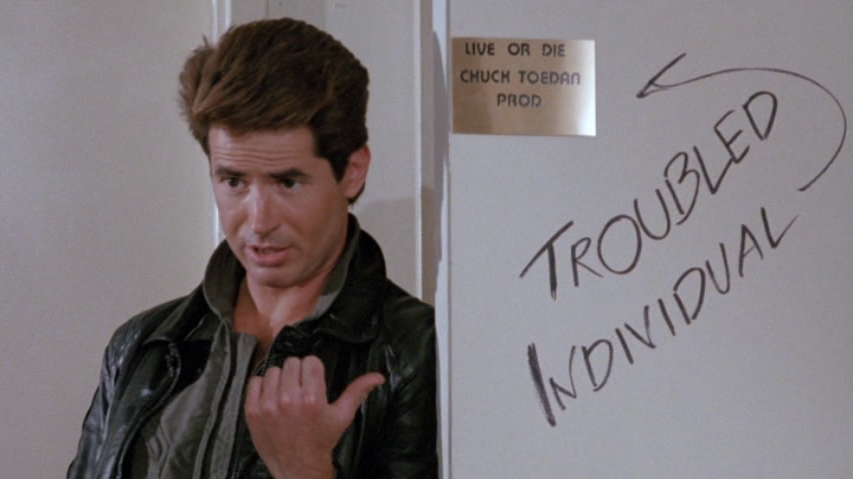

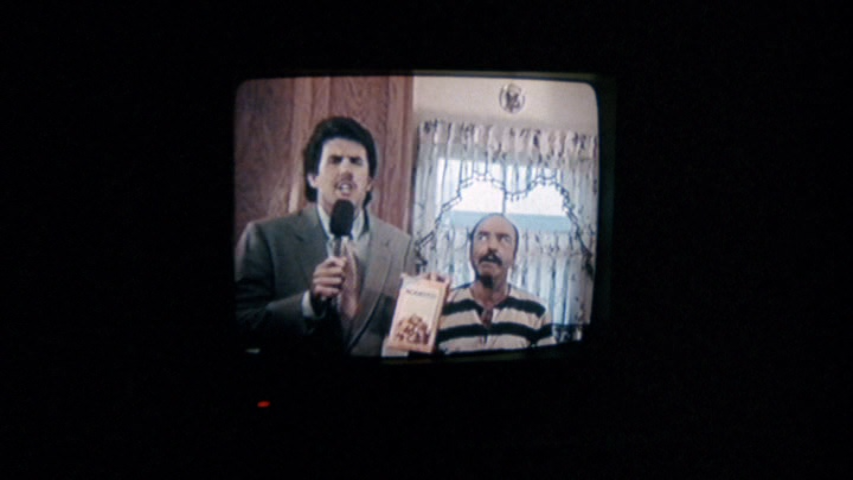

Live or Die is hosted by Chuck Toedan, played by John McCafferty as a character who’s far better described as amoral than evil. He gets no particular thrill out of killing his contestants, but rather respects his role as the modern evolution of a necessary profession: that of executioner.

McCafferty is no Richard Dawson, but he does well enough with this spin on the character type, and it’s nice to follow the experiences of the host rather than one of the show’s contestants.

He plays the role perfectly, which is assisted by his naturally boyish good looks. He’s not the old hand that Dawson is, the seasoned, calm professional…he’s the young buck who enjoys the attention and likes seeing himself on television. He’s easily frazzled and instantly terrified whenever someone or something forces him to step out of his comfort zone. He oozes oily charm, but none of it is calculated. He’s just naturally hollow enough to make for a great game show host.

Chuck, also unlike Damon Killian, is a divisive personality within the world of the film. He has his legions of supporters and mindlessly cheering fans, but he also has a large number of detractors that push back against Live or Die, seeing it for the exploitative horror that it really is.

The thing that allows Chuck to sleep at night is that these are convicts who were already on death row; they’ve been found guilty of their crimes and have already been sentenced to death. What’s wrong with giving them a showy sendoff? With giving them something to look forward to? With giving them a chance to win some money for their families on the way out?

Live or Die has also had a seemingly positive impact on society, with Chuck claiming in a talk show appearance that violent crime has dropped 30% since the game show debuted. It’s keeping viewers entertained and indirectly making their world safer.

Additionally, it offers a small ray of hope in the darkest situations. A caller during that talk show appearance thanks Chuck for killing her father on national television. After all, it allowed him to go out entertaining millions rather than alone in a dank room. His death got to be one of personality rather than procedure.

And early in the film a woman sleeps with Chuck in the hope of convincing him to let her incarcerated boyfriend on the show. If he wins, he’ll go free, and if he loses, maybe she’ll get a parting gift. Either way, everybody wins…and her boyfriend was going to die anyway…

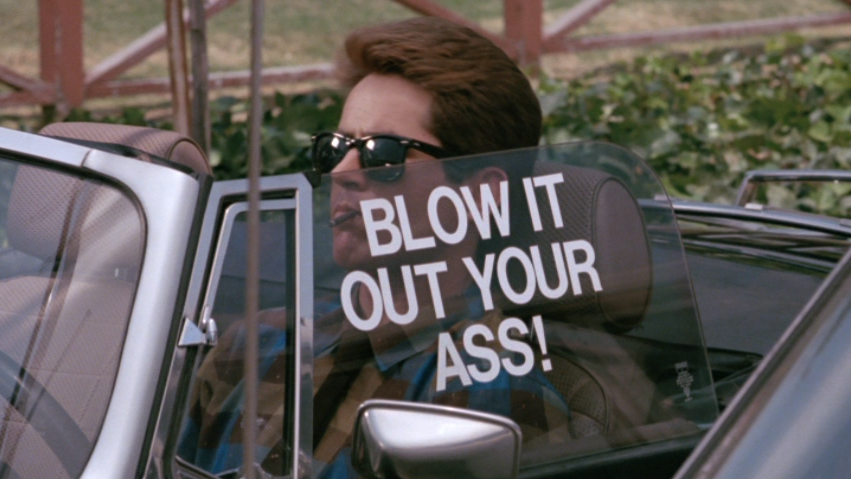

But, of course, it’s public execution, beamed directly into America’s living rooms. It’s not something that makes everybody happy. Protesters hound him at work, for instance, and the frequency of abuse he endures on the road caused him to have this installed:

His most vocal critic is Gloria Sternvirgin, a stand-in for real-world feminist activist Gloria Steinem, played by Robyn Blythe. She represents WAAMAF: Women Against Anything Men Are For, which is a joke that feels orphaned from a Married…With Children script.

Blythe’s performance is the one thing that helps the character feel like less of an unfair jab at feminism than she probably actually is. Chuck and host Roy Montague both call her a bitch at various points, and she’s without question meant to register at first as a ridiculous killjoy, the sort of character we may logically and ethically agree with, but who we can’t stand.

Blythe plays her straight, though, and she’s perhaps the only character that gets to be human and never becomes a cartoon. This may sound like an insult to the other characters, but I assure you it’s only a distinction. Deathrow Gameshow knows exactly what it’s doing, and any shifts in character and tone are done knowingly, if not always expertly.

She holds her own against Chuck and, ultimately, it’s Chuck who comes around, not Gloria. The fact that Deathrow Gameshow aligns itself with her perspective by the end rather than his does quite a bit to declaw the swipes at her character, as does the fact that she and Chuck soon come to share an adversary.

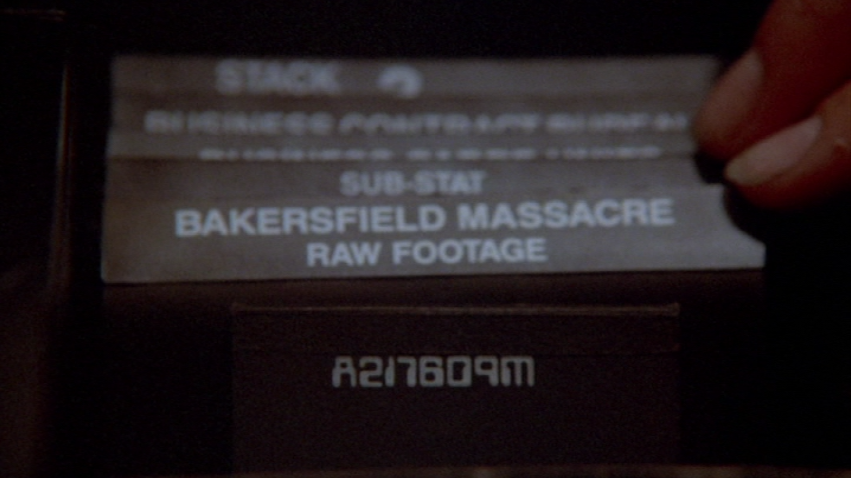

That adversary is Luigi Pappalardo — played by a man with the fantastic mononym Beano — who is seeking vengeance, or at least restitution, for Chuck’s killing of a crime boss, which we see in a flashback that perfectly encompasses everything that makes Deathrow Gameshow work.

We learn that the crime boss, whose name is Spumoni, indeed died on Chuck’s show, but Chuck had no idea who he was. The fact that contestants are only referred to by their prison identification number and never by name is a nice wink toward their dehumanization at the same time it serves as a plot point. (Or, actually, two plot points.)

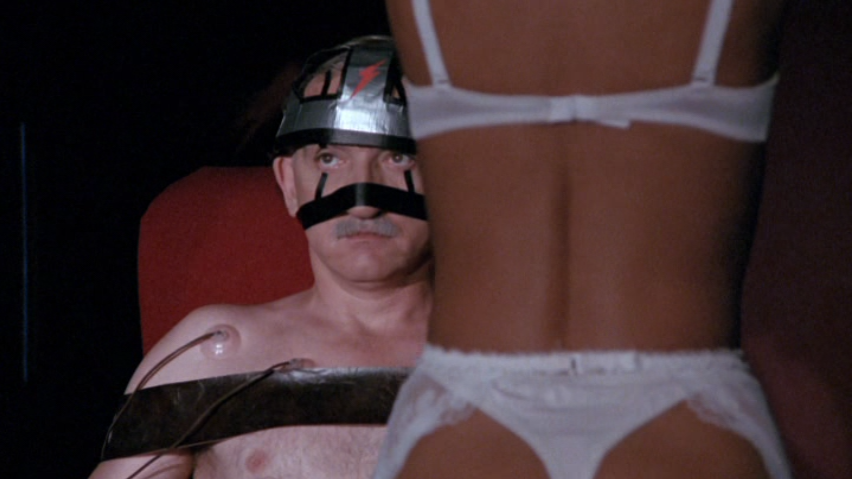

The crime boss has found himself in this show’s equivalent of a physical challenge. He’s stripped naked and rigged up to a machine that will electrocute him if he gets an erection. To win, all he has to do is make it through Chuck’s lovely assistant’s Dance of the Seven Boners.

It’s plot, backstory, riff on the film’s central premise, and juvenile joke all at once.

Of course, when Spumoni dies, it isn’t truly Chuck’s fault, right? He was condemned to death already, and all Chuck did was host a game show. Perhaps Luigi would be upset, and perhaps he’d still seek vengeance, but it’s hard to hold Chuck too accountable for what’s bound to happen…

Except that it doesn’t happen. Spumoni makes it all the way through the performance, and we get the sense that he only barely manages to do so. Spumoni gets to go free.

Chuck, however, places a chummy hand on Spumoni’s shoulder, and the stimulation of physical contact is too much. He fries anyway.

His death was accidental, but it was Chuck’s accident. As a result, our hero has spent the past six months as the target of various threats and attempts on his life. One of these comes immediately after his talk show appearance with Gloria, and he whisks her away from harm. (Don’t worry, though; he won’t be a sympathetic character for at least another hour.) Unfortunately, the fact that she’s seen fleeing with him puts her in Luigi’s crosshairs as well.

At various points throughout the film, Pirro drifts firmly into sketch comedy territory, which surprised and disoriented me on my first viewing. I expected dark humor for sure, but I didn’t expect silly, isolated skits that had nearly nothing to do with the film I was watching.

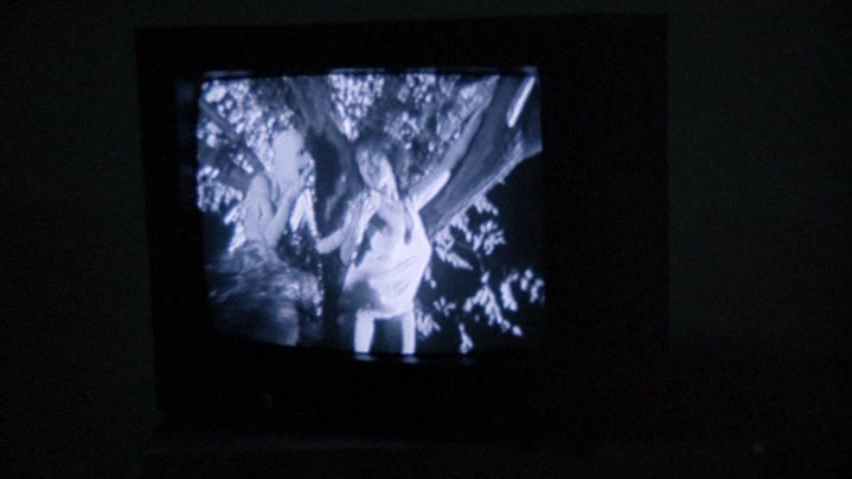

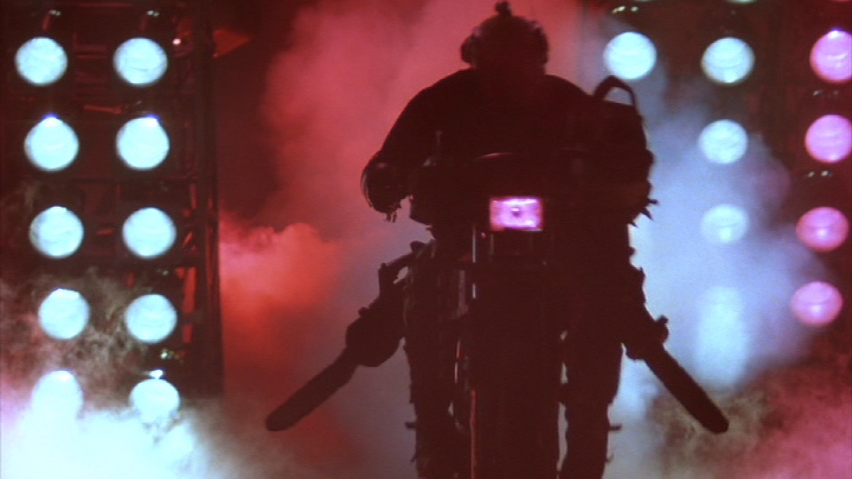

One of these comes during the first round we see of Live or Die. A convict has his head in a guillotine, and if he wants to take it out again he has to identify the famous film he’s shown on the monitor.

We get to watch it with him. A figure wrapped in bandages lunges at a screaming woman, who gets away. The monster lets loose a humorously long string of frustrated profanity.

Recognize the movie? The prisoner didn’t, either. Chuck lets us know the film is called Curses of the Mummy.

A bit later, Pirro shows us slow-motion footage of kids crossing the street, which we cut to several times.

Why? Because Pirro is saving the reveal of the SLOW CHILDREN sign for the very end of the sequence.

The silliness of the jokes works, though. I wanted Pirro to view the horrors he created through a dark lens, but he insisted on seeing them in a fun-house mirror. Once my vision adjusted, I could appreciate the movie for what it actually was. Deathrow Gameshow is frequently dumb, but never stupid.

The best of the dopey gags, though, are the ones that flesh out the media landscape of Pirro’s world.

I’m referring to the television commercials that also take advantage of death row inmates. In one, a horrified mother can’t tell whether the desperate cries of her son being executed are genuine, or the remarkably clear audio quality offered by Glamorex cassette tapes.

In another, a criminal is given two cheese samples and asked to identify which is real and which is imitation. Unfortunately, the commercial is actually for Rodento cheese-flavored rat poison.

Scenes like this certainly make the world seem less real, but they also make it feel more cohesive. Once criminals sentenced to death are turned into entertainment, why not advertise with them, too?

Spumoni is actually the only criminal we see who expresses a desire not to be part of the show. (He did sign a release, though.) The others jump up and down with excitement as they await their turn, engage in banter with Chuck, and enjoy the thrill of the proceedings. (If not their termination point.)

In fact, in one of the film’s best jokes, Luigi takes over the show and releases the prisoners…who then sit down to watch the show themselves. From victim to audience in a literal heartbeat.

Families of the condemned even turn up to watch the prisoners compete live, hoping their loved ones either cheat death or leave them with some prize money as a consolation. In a great, unspoken moment, a contestant’s wife covers her daughter’s eyes but not her son’s.

Then, of course, there’s an angry viewer who accosts Chuck in public. He accuses Chuck of being a despicable human being doing unforgivable things, but we get the sense he never misses an episode. “I’ve been watching your show for two years,” he shouts, “and I think it’s sick!”

Chuck even launches into a “we give the people what they want” speech during his talk show appearance, which coincidentally sounds damned similar to the one Killian delivers at the end of The Running Man.

Deathrow Gameshow understands exactly why a show like Live or Die could succeed. Enough of the people who watch it enjoy it, and those who don’t still can’t pull themselves away. There’s something innately seductive about death, and watching those condemned to it trying to conquer it…well, of course they should cancel that show. But did you see it last night? It was wild…

Chuck offers Luigi a bribe to leave him alone, but the cartoonishly Italian assassin isn’t willing to be paid off. At least, not with money.

Mama Pappalardo happens to be a big fan of Make a Big Deal, another game show that films at the same time as Live or Die. You know exactly where this is going, and Deathrow Gameshow knows you know exactly where this is going, which allows the film to play with its own inevitability.

It does so, and it’s incredible.

Luigi suggests that if Mama Pappalardo can be in the audience for Make a Big Deal, maybe he can forget about that whole unfortunate dead crime boss thing.

Chuck doesn’t have control over Make a Big Deal, but through his secretary he manages to get Mama Pappalardo invited to the show. She even escorts the old woman to the Make a Big Deal studio personally while Chuck and Luigi set the world to rights.

And, of course, Make a Big Deal‘s audience shows up in costume, just like our real-world Let’s Make a Deal. Mama Pappalardo shows up dressed as a prisoner from Alcatraz.

Again, you know exactly where this is going…

Things should be fine; the two game shows film in entirely different studios, after all.

Mama Pappalardo has to use the restroom, however, so she gets out of line.

When she’s done she can’t find her way back, and a helpful young stagehand guides her onto the set of Live or Die.

The methodical plod through these circumstances is tremendously fun to watch unfold. Pirro just needs to get Chuck to throw a lever or something and kill an old woman, but the fact that we establish an entirely different game show with its own, very specific, fan base to get us there is great. Deathrow Gameshow doesn’t have many surprises to offer; it’s just fun to watch it play with its toys.

Of course, none of this would be an issue, except that Chuck didn’t get to see Mama Pappalardo before she headed off to Make a Big Deal. And Luigi hates Chuck’s show and doesn’t want to watch it. And he drags Gloria along to the Italian restaurant across the street, so he doesn’t join his mother at the other game show, either.

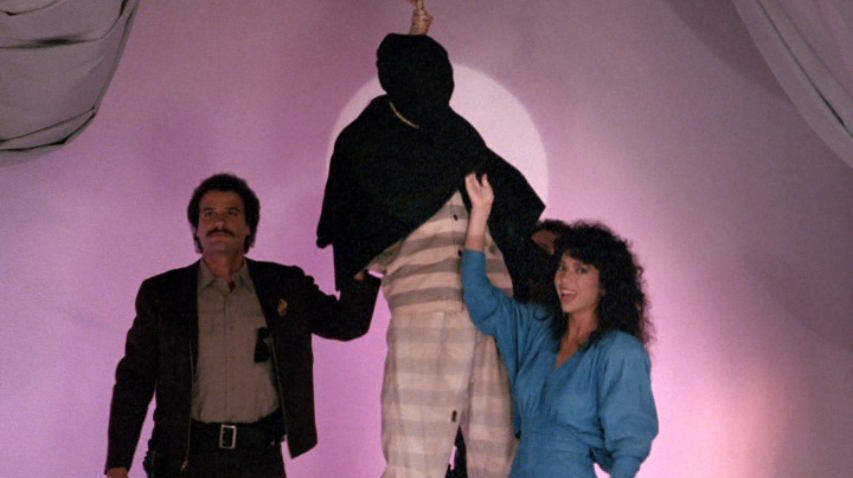

Mama Pappalardo appears on Live or Die, as she must. She’s the only one to buzz in to answer the trivia question, and she gets it right. As she must. Chuck rewards her with a physical challenge. As he must.

And if there’s any doubt about the film’s willingness to play with inevitability — to never undercut expectations but rather to drag them out lovingly — this sequence lays them to rest.

It’s not enough to know Mama Pappalardo is not long for this world; we need to see an old woman holding two canisters of gasoline, hopping weakly through rings of fire.

As she gets near the end of the sequence of flaming rings, Chuck’s lovely assistant blows flames that nearly singe the old lady. She’s not trying to complicate things…she’s just kind of a ditz.

Mama Pappalardo doesn’t explode. She does what no other contestant has done in our presence: she survives. She sets the canisters down next to some candles and celebrates, thinking she’s won Make a Big Deal.

The table collapses. The gasoline ignites. Mama Pappalardo is sprayed all over the studio backlot.

There’s nothing artful about it. Nothing clever. A doddering old lady explodes. But Pirro treats it with the appropriate gravitas: none whatsoever.

I absolutely love Mama Pappalardo. In fitting with the overall tone of the movie, it feels like she stepped right out of a Monty Python skit. In fact, she’s even played by a man in drag: Mark Lasky, who also plays Spumoni.

She’s never fully present in any of scenes, consistently confused and distant. She likely doesn’t know or understand how her son earns his money, and she certainly doesn’t know or understand anything else that’s going on around her.

Her goofy enthusiasm for leaping through the burning hoops is one of the film’s biggest and best laughs, as she finally comes to life in exactly the wrong situation. Nothing we observe or know about Mama Pappalardo suggests that she deserves her fate, which is what makes her explosive exit from the film such a giddy delight.

We know it’s coming, the movie knows we know it’s coming, and then it gives us exactly what we tuned in to see. Deathrow Gameshow is operating on the very same wavelength as Live or Die, and it’s getting the same reactions from its audience as well.

After the show, Chuck learns who he killed and is mortified. He immediately launches a plan to edit her death out of the episode and hide the truth from Luigi, which leads directly to Luigi seeing the footage himself.

The acting in Deathrow Gameshow is no better than we got from Arnold in The Running Man, but it’s far more appropriate to the film. Arnold seemed to be acting in an entirely different movie, operating on a plane of mental existence that wasn’t shared by any of his costars.

Here, none of the actors were in any danger of winning awards for their roles, but they all understood what they were doing, and that makes it work so much better.

They’re ridiculous people in ridiculous situations, saying and doing ridiculous things…but it makes the film feel more real than The Running Man felt, because everything is actually working together rather than the film being at odds with itself. Knowing you’re ridiculous allows you to establish a consistent identity. Not knowing you’re ridiculous leaves you flailing.

In addition to the main characters we’ve already discussed, there are two more worth noting.

The simplest and most successful is Debra Lamb as Chuck’s lovely assistant Shanna Shallow. Like much of the dedicated eye candy on game shows — Vanna White most notably — Shanna doesn’t get anything to say. Not just on Live or Die, but in the larger film itself.

She’s just a presence, and an increasingly bizarre one as we learn that she’s still speechless when the cameras are off, always staring blankly into the middle distance as though she’s been genetically engineered to be the perfect lovely assistant. This isn’t her job…it’s her existence.

Shanna barely even reacts toward the end of the film when Luigi takes over the show and forces the crew into a large cage on set. While they’re all trapped inside, Shanna postures and poses, introducing some imaginary Brand New Car on her right.

It’s funny and well played. Slightly less successful is Darwyn Carson as Chuck’s secretary, Trudy.

I actually feel bad saying so because Carson had far more to do than Lamb, and I don’t think she did a poor job. I think it’s more the case that she’s less defined as a character.

Trudy works best as an unintentional foil for Chuck. We only get a few scenes of the two of them interacting in this way, but it’s some of the best stuff in movie.

CHUCK: Any messages, Trudy?

TRUDY: Yes sir, Mr. Toedan, two I believe. A lady called asking for Lisa Whitman.

CHUCK: Who’s Lisa Whitman?

TRUDY: I don’t know, sir.

CHUCK: Well, what happened then?

TRUDY: She apologized and then hung up.

CHUCK: Trudy?

TRUDY: Yes, sir?

CHUCK: Isn’t it possible that this could have been a wrong number?

TRUDY: No, sir! It rang right here.

CHUCK: What about the other call?

TRUDY: Other call?

CHUCK: You said there were two calls.

TRUDY: Oh, yeah. A lady called asking for Lisa Whitman.

CHUCK: You told me that already.

TRUDY: She must have called back.

It’s corny, sure, and it’s the kind of comedy routine that we’ve seen thousands of times across all media, but it works. It’s funny. It’s the type of exchange that’s fun to write, act out, and watch. It plays well here, and is a welcome drift into a more familiar kind of insanity.

There’s also a great, unacknowledged visual gag involving the various notes Chuck leaves Trudy to clean up her work area…which accumulate so quickly they become their own kind of clutter.

All of this is good, but I get the sense that Deathrow Gameshow only intermittently knows what it wants to do with her. Another running gag, and a far less successful one, involves her secretly masturbating at work. I suppose there’s a way to make that funny or interesting, but Deathrow Gameshow doesn’t manage it.

In a way, that’s fine. In a screwball, wackadoo comedy like this, not every joke needs to (or can be reasonably expected to) land. It’s disappointing, though, because Deathrow Gameshow has stumbled on to several other ways to make Trudy funny, and this feels like a holdover from an earlier version of the script that couldn’t think of anything else for her to do.

I don’t mean to oversell Deathrow Gameshow. It’s not going to change anybody’s life or offer them compelling insight into difficult questions. It is, as they say, just a movie.

But it’s a movie that works. It’s a movie that achieves its own goals. They aren’t lofty goals, but they’re worth shooting for. They give us a movie that’s memorable, a movie with personality, a movie with a lot of great laughs and a few strong digs at the actual media we know, love, and follow.

It’s a cheap movie, but it uses its budget wisely. Setting the vast majority of the action on a game show set is a wise way to keep costs down; just like a real game show, most of it is static and props can be wheeled in or out to suit the changing needs of the scenes.

Pirro claims on his website that the film was produced for $200,000, which I certainly believe. But it went on to make $1.5 million in home video and cable revenue. (I suspect this will grow with the recent rerelease by the fantastic film restoration company Vinegar Syndrome.)

That sounds like a paltry sum, and for a major Hollywood movie it certainly would be. But for a winking labor of love like Deathrow Gameshow, that’s damned impressive. I don’t think the film is due for a universal reappraisal or anything, and whatever level of cult appreciation it holds today is unlikely to increase significantly in the future, but it’s a movie I really enjoyed. It will stick with me as an example of having as much fun as possible with a concept, and then shaking it off completely before it gets stale.

Deathrow Gameshow doesn’t overstay its welcome, nor does it underdeliver. When I told a friend I was reviewing this movie, she asked, “Does it actually have a death row game show?”

It’s the same question anyone should ask if they grew up renting horror movies, making decisions based on title and box art, feeling disappointed when the movie that looked like it should have been awesome offered barely a glimpse of the concept that hooked you.

Deathrow Gameshow delivers what it promises. It doesn’t attempt to trick its audience or even surprise them. You get exactly what you asked for. No more, no less. But in the horror genre, which so frequently fails to live up to its own hype, “no more, no less” can actually mean “significantly more than we should reasonably expect.”

I was disappointed the first time I started watching the film, because I wanted something that would disturb me, upset me, fire me up against the media, against the entertainment industry’s dubious sense of ethics, against the way we view and treat prisoners in this country…

But I got a carefree farce instead. Once I realized it wasn’t the movie I hoped it would be, I was free to enjoy the movie it actually was.

You don’t watch Deathrow Gameshow because you want to see what happens, or because you care about the characters. You watch it because it enjoys itself, and however corny or telegraphed the jokes might be, you end up falling into its spell.

Paul Michael Glaser spent $30 million to make a movie about convicts fighting for their lives on a popular gameshow. Mark Pirro spent $200,000 to make a far superior one. History may not remember Deathrow Gameshow, but I certainly and happily will.