In many ways, I think the best way to review the final episode of season two is to refer back to my review of the final episode of season one.

Season one was, I felt, largely brilliant. It got off to a bit of a sputtering start, but it didn’t take long to carve out a distinct and rewarding identity of its own. Its supporting cast got their chances to shine, we developed Jimmy McGill as a character distinct from Saul Goodman and therefore one worthy of separate study, and it seemed less and less fair to view the show in the shadow of Breaking Bad.

It wasn’t perfect, but it was often great. And Rhea Seehorn, a relative newcomer, proved herself to be the most valuable member of a cast that included old pros like Bob Odenkirk, Michael McKean, and Ed Begley, Jr. In short, Better Call Saul had promise. That was no surprise. What was surprising was how quickly it fulfilled that promise.

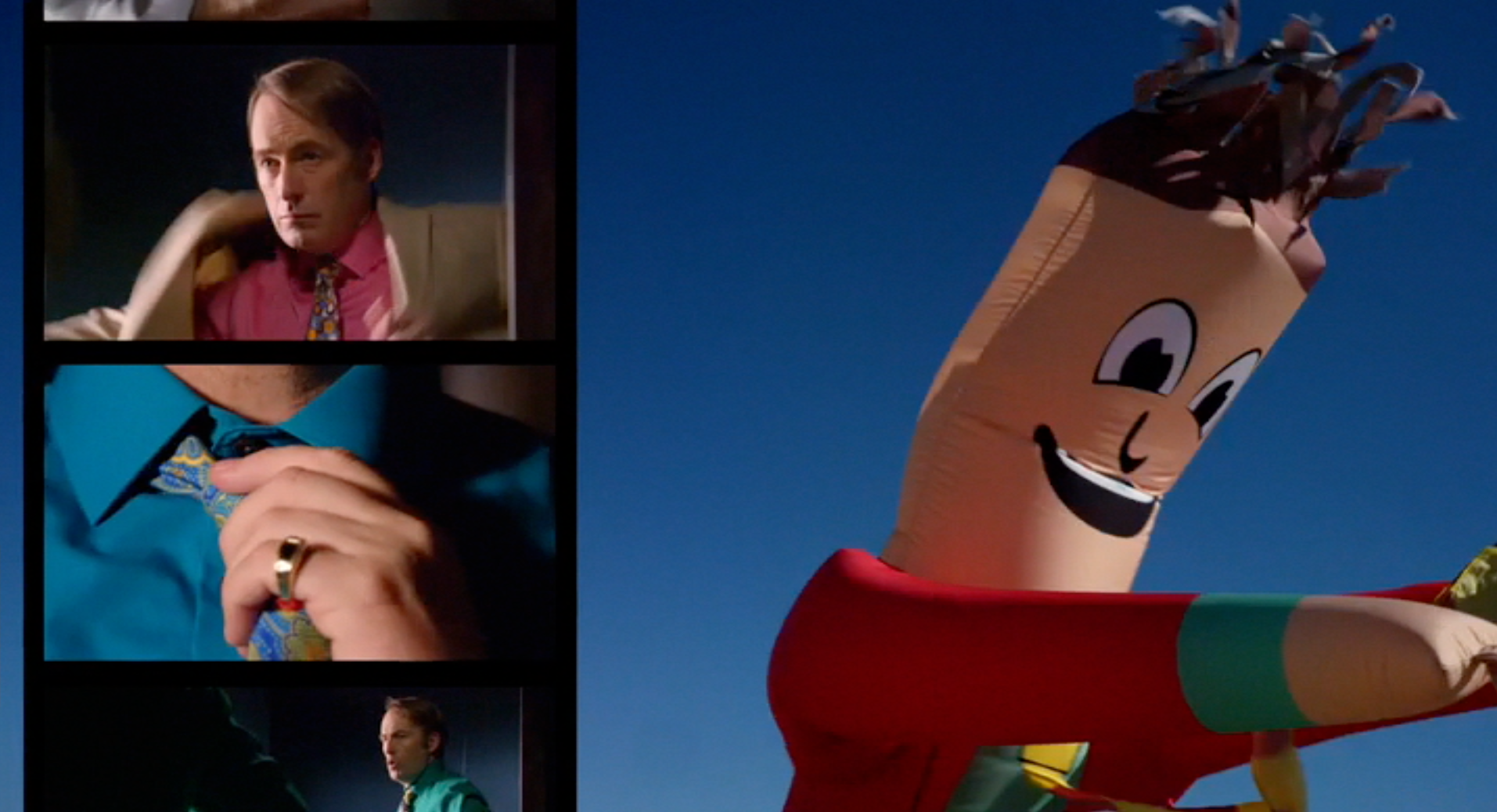

Then came the final episode of the season, “Marco,” which wasn’t exactly the best thing the show could have done. Most disappointing was its ending, in which Jimmy turns down a position at Davis & Main so that he can hop into a phone booth and emerge moments later as Saul Goodman.

It was oddly graceless, and almost insulting to a viewer who would have spend the previous nine episodes and change invested in Jimmy’s story. “Anyway, I’m Saul now, so forget all that.”

The show deserved better. Here’s what I said about that in my review:

Jimmy checks his messages and finds that he has clients — actual people for whom he is doing actual good, and who pay him actual money — waiting for him, and it feels like a nice moment of awakening for the character. [Kim] tells him that he stands a good chance of being hired on at another law firm…and hands us a great setup for where season two can go.

But ah, the Sickle! Jimmy comes home, stands in a parking lot for a little bit, then says “Fuck it, I’ll be a bad guy!” It’s an unconvincing reversal, to say the least, and it again feels so effortful. It’s a forced conclusion that speeds us toward Jimmy’s eventual transition into Saul, which works against the quiet, tragic slowness we’ve known all season. […] With the high highs of the previous episodes still so strongly in mind, I find it hard to believe that that’s where we actually ended things.

[…] A far more intriguing end to season one would have been Jimmy getting hired on at [Davis & Main]. He could spend “Marco” doing largely the same things, coming to largely the same conclusion as he comes outside of that church. He decides that he can do this, and sets out to make a name for himself at a reputable firm.

…at which points he finds it extremely difficult, makes an ass out of himself, and despite his best efforts keeps getting beaten back to the man who will eventually give up and become Saul.

That could have been a great series of episodes. It would have proven to him that he couldn’t handle what he expected to handle. It would have given Chuck’s “chimp with a machine gun” concern some retroactive weight, as Jimmy fails to live up to the sacred practice of law.

I’m not saying that I know the direction of this show better than anyone else does, but I do know that Kim’s arrangement floods my mind with possible storylines, whereas “I’m Saul Goodman, and you’re not! G’night everyone!!” doesn’t.

Forgive the long quote, but its length is deliberate: doesn’t season two seem like it addressed that concern specifically?

Not that I suspect anyone involved with the show read my reviews, much less took my criticisms to heart when working on the next batch of episodes. But I do think that my concerns must have been shared by at least someone on the writing staff. Why else would season two have begun with Jimmy literally undoing the decision he made at the end of season one? It must be because Davis & Main floods the mind with possible storylines, whereas ditching all that for Goodmanism just gives us the same stuff we already saw on Breaking Bad.

Funnily enough, the first episode of season two even shares my metaphor of a light switch:

I’ll watch season two, unquestionably. But Jimmy deciding he’s going to be a crooked shit is too easy. We already know where he ends up, so this isn’t surprising. It should have been something more momentous than flipping a light switch, which is what he might as well have done.

But now I’m just bragging.

My point is, Better Call Saul was excellent, but it had some issues…mainly at the very beginning and at the very end. Season two deliberately set out to correct those issues, even going so far as to have Jimmy immediately reverse the very decision that season one led to. It was course correction for both the character and the show, and as a result season two deposits us in much more interesting territory than season one did.

Season one said, “Here’s that guy you like.”

Season two now says, “Here’s these characters you’re still getting to know. And they’re fucked.”

We can get Mike’s story out of the way easily enough: it ends with a beginning. Instead of assassinating Hector with a sniper rifle, our aging hitman finds his view blocked. Some time passes (in an impressively tense scene, considering we know full well he doesn’t kill Hector) and then there’s the sound of Mike’s car horn. Someone’s wedged a stick against the steering wheel to set it off, and they’ve left a simple note: DON’T.

For starters, that’s pretty similar to the “Go home, Walter” phone call from “Thirty-Eight Snub,” which stops Walt from killing Gus. (Well…stops him for the time being.) That’s nice.

But the larger development here is that…well, it’s Gus, isn’t it? Gus tailed Mike, I guess, for some reason, and stopped him from killing Hector, I guess, for some reason. And he waited a long time to wedge that stick, too; if Mike’s view hadn’t have been blocked by Nacho, Hector could have been shot dead 150 times over. So…whatever. I’m not really sure what happened here, but FRING’S BACK so we know it’ll be worth waiting around to find out.

It’s Jimmy and Chuck, though, who are really in an interesting spot as the season ends. Chuck tricks Jimmy into confessing his felony, and records him doing so.

Okay. So, no, that doesn’t sound like much when you just see it in print like that.

What’s interesting is how Chuck plays it. How villainously he plays it.

He resigns from Hamlin, Hamlin & McGill. As in, actually resigns. Howard isn’t in on the deception, but Chuck knows that if he quits, Howard will call Jimmy for some insight. And once Jimmy finds out Chuck quit, he’ll rush over to check on him. And once Jimmy shows up, Chuck will act a little extra crazy, to disarm Jimmy and make him feel bad. And once Jimmy feels bad, he’ll come clean…and Chuck will have it all on tape.

And it plays out exactly that way. Of course it does. Chuck’s the one who pieced together every detail of Jimmy’s crime, in sequence. He knows how this stuff works.

His deception is clever, and in line with what we know and suspect about the character. Sure. But what really makes it sting is that Jimmy spends a huge portion of this episode the same way he spent a huge portion of season one, and much of season two: caring for Chuck. Sitting with Chuck. Refusing to leave Chuck. Doing whatever is in Chuck’s best interest to keep him safe and healthy.

This is what Chuck takes advantage of. He knows Jimmy will drop everything the moment Chuck needs him. Chuck abuses his brother’s good side in order to prove his bad side.

That’s the weight of twenty good episodes making that cliffhanger work as well as it does.

And it also gives us some great insight into who Jimmy is. We know he’s flawed. We know he’s unscrupulous. We know he’s easily led astray.

But now we also know that he’d willingly commit a felony just to help the woman he loves.

And he’d confess to that felony just to make his sick brother feel better.

This leaves us with a lot of possible storylines for season three. This is not closure that needs to be reversed. This is one story becoming, in an instant, another story entirely.

There’s fallout to anticipate. There will be consequences. And, eventually, Jimmy will lose both Kim and Chuck as a result.

As a direct result? Probably not; the show hopefully has a few good years left in it.

But as a result of being Jimmy? As a result of being who Jimmy is?

Yes.

And that’s already a more interesting story than Saul Goodman’s would have been.

Roll on, season three.