Calling all writers / humorists / parodists / gamers / whatever else you are. This is an official announcement of a one-off fiction anthology that I will be assembling, and I need your submissions!

The anthology is called The Lost Worlds of Power, and I would love to get as many submissions as possible, so please pass this on to any writers you know who might be interested in being published in a collection!

THE LOST WORLDS OF POWER

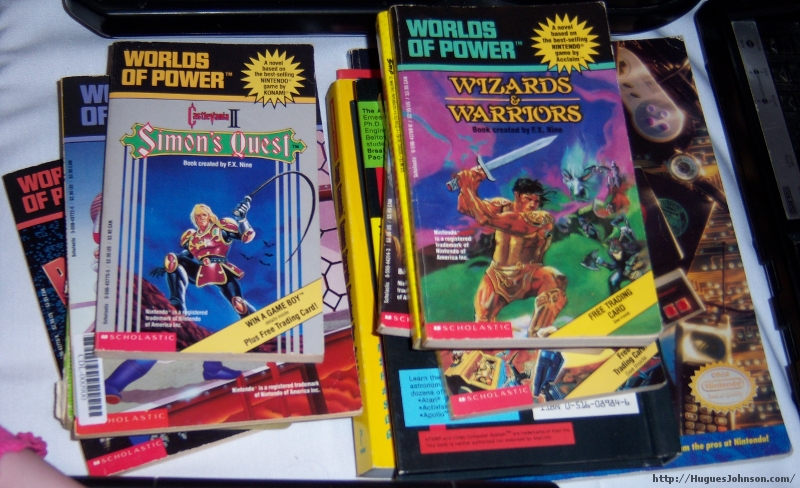

The Concept: Worlds of Power was a series of notoriously awful and totally inaccurate novels based on popular video games. What we’re doing is writing more of them! I want you to choose a video game (see the rules below) and novelize it. If you aren’t familiar with Worlds of Power, you can read a bit about the series here. You can also read my reviews of two of the books (with excerpts) here and here.

The Final Product: The Lost Worlds of Power will be an electronic, one-off fiction anthology. I will not sell it, and will make no profit off of it. In fact, I will pay out of pocket to have it professionally designed and formatted…and hopefully illustrated. I will host it here for free download, and I’d encourage anyone interested to host it and distribute it themselves as well. It should be something a lot of people can enjoy, and your submission should see a wide and appreciative audience!

The Style: You’ll be writing a “lost” installment in the Worlds of Power series! The obvious route here would be to write something intentionally bad, but that’s not the route you have to take. All styles, lengths and degrees of artistic merit are wanted. If you want to be outlandish and silly, that’s perfect. If you want to write a heart-stopping work of emotional brilliance based on T&C Surf Designs, that’s equally perfect!

The Length: There’s no hard and fast length requirement. Use as much or as little space as you like. The original Worlds of Power books were only around 100 pages long, with large type, so probably around 40 or 45 pages of traditional text. You can shoot for that, or you can let the spirit move you. Personally, I’d encourage you to do the latter.

The Rules: Read carefully, and make sure you adhere to the following rules when submitting:

– Your “novel” must be based on a game that was released on the NES. It doesn’t have to be a game exclusive to the NES, there just needs to be a version of it that existed for the NES (or Famicom). If it was something that was originally an arcade game or was later ported to the SNES or Genesis, that’s fine!

– Games that were actually adapted into Worlds of Power books are not eligible. (Remember, the idea is to write a “lost” installment in the series.) Therefore Blaster Master, Metal Gear, Ninja Gaiden, Castlevania II, Wizards and Warriors, Bionic Commando, Infiltrator, Shadowgate, Mega Man 2 and Bases Loaded 2 are all off limits. You can, however, base your submission on a different game from those series.

– Only one adaptation of any given game will be selected for inclusion. In essence, if I get five submissions based on Super Mario Bros., I will only choose one of them, even if they’re all very good. For this reason it’s probably best to either choose something relatively less popular, or make sure you’re confident that the adaptation you’re writing will be the absolute best I receive!

– Be creative! Don’t just write out the events of the game…have fun with them! Get things wrong. Grossly misunderstand your protagonist’s motives. Skip over the best fights and spend time on mundane interactions with townsfolk! The Worlds of Power books are legendarily off the mark, so warp your filter a little bit! Do your Goombas look like carrots instead of mushrooms? Is Link’s traveling companion a rapping leprechaun? Does the dog from Duck Hunt travel through time and solve mysteries? Are your ideas better than these? I hope so, and I can’t wait to find out!

– You retain the rights to your submission (barring, obviously, any trademarked characters or titles you incorporate). I will only have the rights to collect and distribute it if you are selected for inclusion.

– Multiple submissions from the same author are allowed.

– We reserve the right to edit submissions for spelling, punctuation and formatting reasons.

What if I Don’t Know Anything About Video Games? The original Worlds of Power authors didn’t either! Just use the characters, settings, and / or plots as a springboard. From there, this is your story to tell!

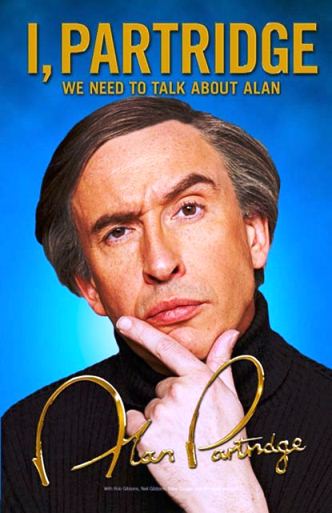

The Prize: There is no financial or physical prize…just inclusion in the one-off Lost Worlds of Power collection. Still, it’ll be fun, and being published in a fiction anthology, no matter how small, is something that will be a great credit toward getting your future work published elsewhere! You’ll also be eligible for the title of First Person to Ever Brag About Writing a Worlds of Power Book.

The Deadline: Januaray 31, 2014. I know. That’s soon. Believe me, that’s a good thing. The Worlds of Power books aren’t known for being particularly well thought-out.

All submissions and questions should be sent to reed.philipj at gmail.com. I’m not picky about the format of your submission, as long as it’s a common file type (.doc, .rtf, .txt, etc.) and you’ve taken the time to proofread before sending it in.

Please let me know if you are interested in submitting. If enough folks are I’ll be more flexible with the deadline. The more the merrier, and I look forward to seeing your submissions!

Credit to James Lawless, die-hard Worlds of Power fan, for the idea!