For three weeks each year, beginning April 1, I take a look at three related comedy films. These could be films from the same series, films with the same actor, films with a common theme…any connection, really. This year I decided to look at three films based on novelty songs.

I’ll come clean with you up front: I expected to see three terrible movies. To come even more clean, that’s exactly what happened. What I didn’t expect is that Harper Valley PTA would be the one that came closest to doing something like this exactly right.

Let me state clearly that Harper Valley PTA is not a great film. At least, the version we got is not a great film. I strongly suspect it went through several iterations, and the ghost of a really strong one peeks through just often enough that it becomes instructive.

“Harper Valley PTA” was the claim to fame for one-hit-wonder Jeannie C. Riley. If you haven’t heard it before, it might be worth listening before reading on.

The idea of taking a three-minute song and adapting it into a 90-minute film is fascinating to me. I know decisions like this are made for financial reasons rather than creative ones — Harper Valley PTA was essentially tie-in merchandise — but it’s still interesting to explore the process of adaptation. Or, possibly, translation.

Riley didn’t write “Harper Valley PTA” and was not the first to perform it, but it’s her version, released in 1968, that made the song famous, and it’s the one that inspired the film. It’s a song that feels like both a perfect and terrible choice for cinematic adaptation.

On the positive side of the ledger, there’s the fact that it contains a litany of named characters with distinguishing traits, meaning all a filmmaker really needs to do is write a story around them. On the negative side, there’s the fact that that story was already told in the song.

“Harper Valley PTA” is about Ms. Johnson, a widow with a teenage daughter. The titular organization disapproves of Ms. Johnson’s behavior / personality / fashion, and sends her daughter home with a letter to that effect. Ms. Johnson turns up at the next meeting of the Harper Valley PTA to air their dirty laundry in return.

And…that’s it, right?

In a sense, yes, and if that’s all a listener pulls from the song, that’s fine. But there are a few other layers at play.

For starters, Ms. Johnson correctly identifies the letter as a personal attack masquerading as concern for her daughter. The Harper Valley PTA isn’t truly worried that Ms. Johnson’s behavior will negatively impact her child’s future; they just don’t like that a young, attractive, single mother is living the life she wants to live and dressing the way she wants to dress.

Admittedly, this was a fairly quaint perspective even by 1968; the culture clash between the generation that came of age in the mid-50s and the one that came of age in the mid-60s was obviously still unfolding, but “Harper Valley PTA” was far from the first piece of popular media to make note of the conflict.

And it doesn’t do much more than make note of the conflict. Ms. Johnson likes her miniskirts, and the members of the Harper Valley PTA don’t. Ms. Johnson likes casual dating, and the members of the Harper Valley PTA don’t. Ms. Johnson refuses to behave the way they think a widow should, but the Harper Valley PTA insists that she conform.

That’s about as insightful as the song gets. Hearing Ms. Johnson unload on the individual members of the Harper Valley PTA, dragging their secret shames out of the shadows for all to see and then telling them all to get stuffed, is cathartic and all, but it’s also superficial. She draws attention to their alcoholism and flirtatiousness and illegitimate children, calls them hypocrites, and leaves. The singer — revealing herself to be Ms. Johnson’s daughter — celebrates “the day my mama socked it to the Harper Valley PTA,” and we’re left to imagine a group of hypocrites left speechless, clutching their pearls.

It’s easy to picture this serving as the climax of a film, and therefore the easy way to turn “Harper Valley PTA” into one would be to build toward this with long stretches of Ms. Johnson learning of their hypocrisies, turning the same blind eye to them that (presumably) the rest of the townspeople do, until that letter comes, she stops playing nice, and she launches into her big speech.

That could have worked fine, but the film’s first unexpectedly wise decision is that it doesn’t close with this big moment; it opens with it. The bulk of the movie, cleverly, is the fallout from Ms. Johnson’s theatrics, and not the gradually building catalyst for them.

This is smart for a number of reasons, not least the fact that it front-loads the familiarity. Anyone who had heard the song in the 10 years between its release and the release of this film knew the lyrics, so ending the movie there wouldn’t be all that interesting. Beginning the story there, though, and suggesting that there’s an entire movie’s worth of development to follow, is, frankly, a better idea than Harper Valley PTA knows what to do with.

Ultimately, the movie we ended up with is one in almost constant conflict with itself. It’s both an insightful drama with minor comic elements, and a broad, idiotic farce.

It feels as though an early draft of the film had a grounded satirical tone, a later draft relied almost exclusively on slapstick, and these drafts were merged inelegantly for shooting. Or, perhaps, one version of the film was shot and early feedback encouraged them to retool the film significantly. There are a few things that point to this being a possibility, but I’ll get to those later.

For now, let’s talk about the more serious elements of the film, as they work quite well and illustrate the potential for a great movie being made from a frivolous song.

The serious draft of the film would have focused on Dee, Ms. Johnson’s daughter. There’s enough reason to believe this to have been an early intention; the song itself was sung from the daughter’s perspective. We learn quickly in the film that her perspective is by far the more interesting one.

What we learn from the time we spend with Dee is that…well, it kind of sucks to have a mom like Stella Johnson.

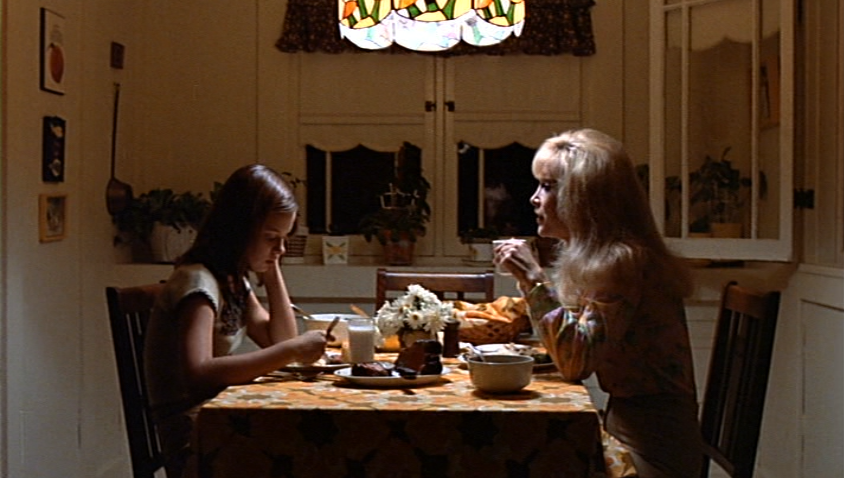

Our first glimpse of her home life sees Dee returning from school to a locked door. Inside, her mother drinks and sings noisily with friends, having lost all track of time. Dee hammers on the door and rings the doorbell, unheard.

It’s upsetting to her, and when her mother finally remembers she exists and opens the door, Dee blows immediately past her and into her own bedroom. Stella picks up on her obvious disapproval and rather than apologize or comfort her, she sarcastically promises that she’ll start sipping tea with church ladies instead.

In other words, she turns her own daughter’s complaint against her, and it’s easy to imagine how this makes Dee feel. She’s been given a letter to take home about her mother’s shitty behavior, and then returns home to be surrounded by it and reminded that, yeah, it actually is kind of shitty.

The clash between her mother and the Harper Valley PTA may well be a fiery one, but neither side — no matter what they say — really cares about how Dee feels about this. Each side in the fight has their own feelings about how life in a small town is to be lived, and neither of them are focused on the impact any of this has on the young girl at the center of it.

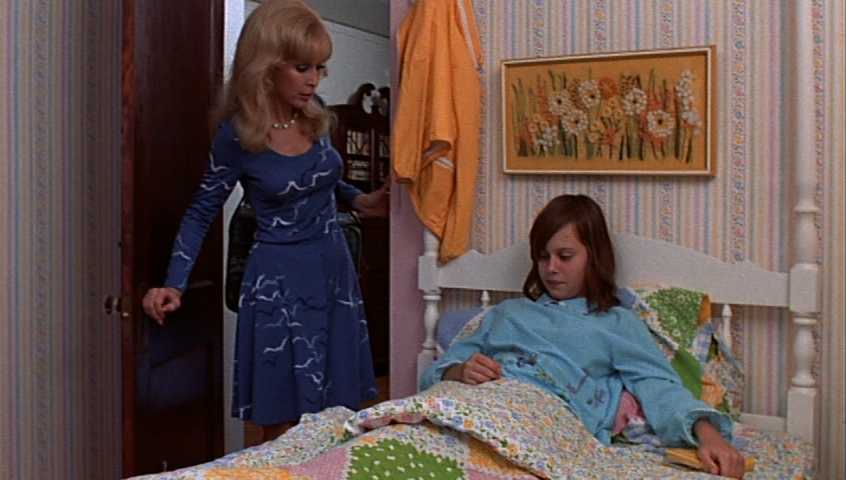

I say it’s easy to imagine how Dee feels, and that’s mainly due to Susan Swift’s performance as the girl. She’s not an especially good child actor when it comes to delivering her lines — though, trust me, I’ve seen far worse — but she is an absolutely fantastic physical actor.

Everything from the way she walks to the way she sits to the expressions on her face sells Dee’s embarrassment and frustration on impressively deep levels. It’s difficult to watch her and not feel protective. This is a girl who is getting hurt, in the middle of a conflict that both sides are about to knowingly escalate.

The most brutal part comes soon afterward, when Stella goes to the next PTA meeting to deliver her speech. She takes a clearly uncomfortable Dee with her, and the girl’s body language is exquisite. Whether this was Swift’s insightful interpretation of the character or some extremely well-considered direction, I can’t know. I suspect it’s the former, though, as none of the other actors seem to have received direction this good.

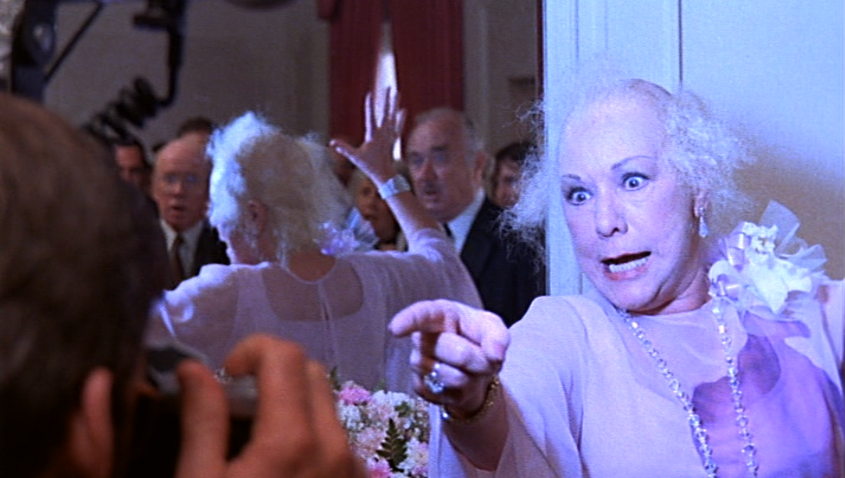

Dee squirms and tries to detach emotionally as Stella stands up, interrupts the meeting, speaks over objections, and ultimately takes the stage, where she delivers her calculated takedown of (nearly) every member of the PTA. When Stella finishes she steps down off the stage and tells Dee they’re leaving.

Dee takes a long time to process this, either completely numbed by the experience or mortified that the attention her mother kicked up is now on her as well. Stella walks away. Dee sits. Is it more embarrassing to leave with all of these eyes on her, or to sit quietly until the end of the meeting and pretend, somehow, that she’s not related to that woman who just commanded her to follow?

In the song, Ms. Johnson’s daughter sounds triumphant, the entire thing a paean to her mother’s theatrical bravery. And maybe Dee, at some later point, will sing about this in similar celebration.

But how did it feel to be there, then, in that seat, knowing you’d be the one who had to be at school tomorrow with these people’s kids? How did it feel to watch this conflict explode when you’d wished it would just go away? How did it feel to know that yesterday about a dozen people were talking about what a piece of shit your mother was, and tomorrow everyone else will be talking about it as well?

In the song, it’s fair to assume Ms. Johnson’s daughter is enough like her that she shares her mother’s opinion on and reaction to the matter. In the film, we’re given explicit indications otherwise. And that’s where “Harper Valley PTA” could, and nearly does, find its mileage as a full-length motion picture.

I started to suspect that the film had gone through multiple conflicting versions during a short scene that quickly follows the speech. In it, Dee writes in her diary and we hear her thoughts; she was proud of and amused by her mother. And those things are fine, but they don’t accurately reflect what we saw of Dee’s own response in the moment, or what we’ll see soon after this.

The scene, with narration that could easily have been added well after the fact and which isn’t employed anywhere else in the film, seems like a corrective action, as though a test audience or the studio found it difficult to stay on Stella’s side if her actions were upsetting her daughter. This “it’s okay really it is” moment feels far more like a decision made in the editing booth than a natural development of the narrative.

In fact, it’s followed by a number of scenes in which Dee is clearly not okay, such as when she comes home from school to find that vandals have toilet-papered her house, or when she pretends to be sick to avoid mockery from her classmates, or when she avoids eye contact and conversation with her mother over dinner.

All of this is the direct fallout from her mother’s decidedly over-the-top display. Stella kicked the hornet’s nest, and it’s Dee that ends up getting stung. It’s a life crisis manufactured by the woman she relies on to protect her.

I think it was pretty likely that Dee would have ended the film in support of her mother, but audiences needed that promise well before it was earned by the narrative. As such we have an understandably mopey Dee followed by a bizarrely reassured and happy one and then our understandably mopey Dee again, in manic succession. Tear out that brief moment with the diary and we have a pretty effective character sketch of a child who doesn’t feel at home with her own mother.

Sadly, that’s not all we’d have to change to make Harper Valley PTA a better film on the whole. Because while Dee’s perspective gives her fraction of the movie a relatable emotional journey, Stella’s gives us a half-assed sitcom.

I’m not using “sitcom” here to be dismissive (that’s why I used “half-assed”), but because that’s genuinely what the movie often feels like. Sometimes that’s down to things like the film’s low budget, its generic sets, and its uninspired blocking, but it’s also down to specific creative decisions made at almost every turn.

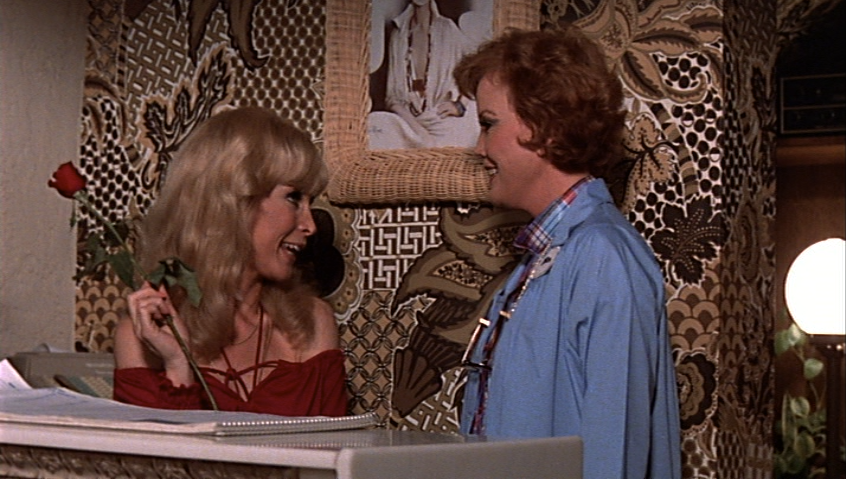

For starters, there’s the cast. Stella is played by Barbara Eden, best known for playing the title role in I Dream of Jeannie. Her best friend Alice is played by Nanette Fabray, a character actor who appeared in many television comedies before this, including The Carol Burnett Show. Other cast members include Louis Nye (The Steve Allen Show), Paul Paulsen (The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour), and Bob Hastings (McHale’s Navy).

It was a cast with more notable TV chops than film experience, and a number of scenes even end with a comical freeze frame and music sting as though it’s a sitcom going to commercial.

In fact, if it weren’t for the more grounded Dee material, the film would be indistinguishable from one of those “movies” created by stitching together several sequential episodes of a sitcom. Each version of the film has to elbow the other out of the way to get any attention.

I might as well bring up here that Harper Valley PTA actually did briefly become a sitcom in 1981, but that’s far enough removed from the movie and shares only one actor (Eden), so as much as I’d love to see the zany aspects of the film as a deliberate dry run for the TV show, I think the structural similarities are coincidental.

Stella’s share of the story is not only a more overtly comical one; it’s an outright wacky one full of slapstick hijinx. It even unfolds in a decidedly episodic manner.

One by one, Stella sets about taking revenge on each member of the Harper Valley PTA, with no narrative overlap or connection between these sequences at all. Stella selects a victim, Stella makes and executes a plan, the victim makes a funny face. Then we put all of those toys away and move on to the next victim. These sequences all feel like miniature sitcom episodes that could be scrambled up and aired in whatever sequence the network likes.

My main issue with Stella’s string of revenge plots is that it robs the movie of any kind of longform pacing. The action needs to rise, rise, rise, climax, and fall, after which the cycle repeats. Again and again and again. It gets exhausting to watch very quickly, as the movie keeps feeling like it’s ending. Not in a narrative sense of course, but in a structural sense, and Harper Valley PTA begins to feel like a skipping record, building to the same thing over and over again without ever getting anywhere.

Compared to the direct simplicity of the song, in which Stella’s “revenge” is summarized in a single line (“This is just a little Peyton Place, and you’re all Harper Valley hypocrites,” which indeed made it into the film), this feels loose and padded. I of course understand that expanding the content of the song to something like 2,900% of its original runtime requires additional material, but Dee’s story — and an element of Stella’s I’ll get to later — could have easily filled the space for the better.

Instead, Stella plays increasingly cartoonish and impossible pranks. The film is a comedy, of course, and comedy is welcome to occupy any plane of reality it likes, but we can’t keep one foot in the real world and the other in Wacky Land, shifting back and forth from scene to scene.

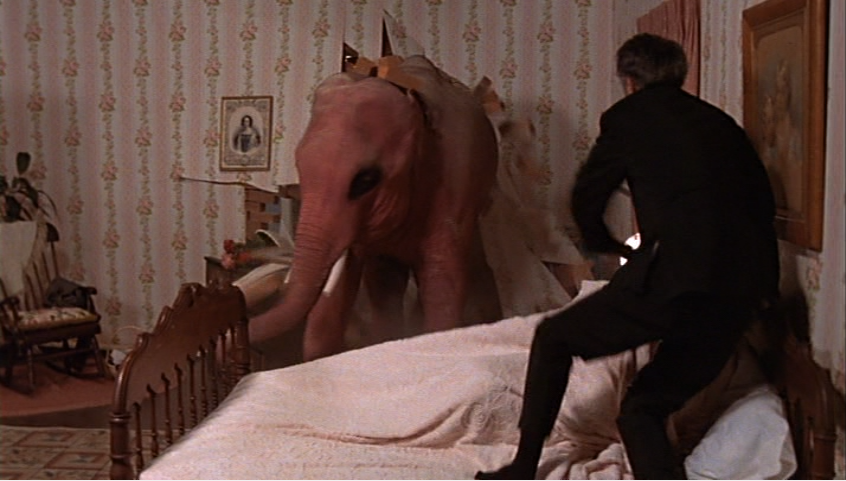

A perfect illustration of the film’s conflicting sensibilities comes in one prank that involves Stella setting a bunch of elephants loose to stampede through someone’s house, demolishing it with him and his wife inside.

It’s played for laughs, and that’s okay; destruction can be funny. But compared to the earlier scene in which a rock through Stella’s window is played with realistic, sincere concern, this represents massive tonal whiplash.

A rock through the window indicates serious familial worry in the same film that elephants smashing someone’s entire house to pieces represents light comedy.

I’d wager that if you showed someone unfamiliar with the film both of those scenes in complete isolation, they’d conclude that they came from two different movies. What’s more, I’m not sure they’d believe otherwise, no matter how hard you tried to convince them.

The truly frustrating thing about the pranks, though, is that they start out quite well.

As in the original song, Stella calls out PTA member Bobby Taylor for repeatedly hitting on her after she’s made it clear it isn’t welcome. The fact that she calls him out in front of Mrs. Taylor at the meeting is understandable; it’s a matter she tried to address with him directly, he didn’t listen, and she’s pushing back harder. It’s difficult to feel sympathy for Bobby Taylor because he was already given his chance to back off, and he decided not to.

In the film, she runs into him at Kelly’s Bar, after calling him out at the PTA meeting. And, of course, he hits on her again.

He’s actively demonstrating to her that he’s learned nothing and does not intend to take no for an answer, so it’s nearly impossible to hold it against Stella when she humiliates him. It is, after all, just a louder way of her saying “no.”

Bobby Taylor plies her with alcohol while ordering ginger ale for himself. His motives are clear. She offers to get a hotel room with him for the night, and he excitedly accepts. No sooner are they in the room together than he strips naked, ready to fuck a drunk woman while his wife wonders where he is.

He’s a pretty shitty guy, and we’re safely on Stella’s side when she kicks him out of the room and locks the door.

That’s totally fair, and the film has every right to reach for the fun sight gag of Bobby Taylor wrapping a firehose around himself to hide his nakedness. It’s a fair escalation of the comedy, with Bobby Taylor’s predicament compounding itself in ways Stella couldn’t have planned.

A cop nabs Bobby Taylor for strutting around in the nude (“Where’s the fire?” being a genuinely funny line), and the movie seems like it might find an interesting groove.

From there, though, Stella deliberately targets the PTA members and manufactures embarrassments for them. That’s a very different thing from rebuffing unwelcome advances. She actively interferes with their lives while they are not interfering with her or anyone else.

In some cases, it’s just irrelevant, as when she makes Flora Simpson-Reilly’s hair fall out at a formal engagement. Other times it’s clear entrapment, as when she sends a judo expert to Kirby Baker, the real estate agent, to flirt with him, beat the tar out of him, and then pretend he tried to rape her.

Then there are just utterly awful things it’s hard to imagine Stella doing. Yes, even more awful than demolishing somebody’s home in the middle of the night.

The Widow Jones gets off pretty easily in the original song, with Ms. Johnson suggesting only that she should “keep her window shades pulled completely down.” We could read into that a number of things, but that’s all we’re actually told.

In the film, the Widow Jones is a teacher. Stella borrows a video camera and secretly videotapes her having sex with someone. Then she splices the footage, somehow, into a sexual education filmstrip that the Widow Jones shows her class. Which Dee is in, but, frankly, secretly videotaping a teacher getting fucked and showing it to her underage students is a bizarre enough setup for comedy before the fact that she’s showing this to her daughter even enters into things.

It’s a profoundly misjudged gag, and it’s hard to imagine what anyone is meant to find amusing here. Unless secretly videotaping your neighbors having sex and then circulating the footage was somehow more acceptable in 1978, and it’s just those damned liberal snowflakes who ruined it for everyone.

There are a few sparks of inspiration throughout Stella’s antics, mainly involving her hairdresser friend, Alice. The fact that Stella would go to her for the town’s juicy gossip — thereby learning of the hypocrisies of the Harper Valley PTA — makes sense, and it at least theoretically grounds Stella in a recognizable social dynamic.

I also like Willis, the decent guy on the Harper Valley PTA who takes Stella’s side after she stands up to the group. He tells her that he was out of town when the PTA wrote her that letter and he never would have signed such a thing.

They, of course, start a budding romance, and it’s nice, but it also leads to what is certainly an unnecessary plot strand in an already bloated movie in which Stella runs for president of the Harper Valley PTA, which itself involves Bobby Taylor hiring goons to kidnap the town’s notary public and builds to a car chase in which everyone is dressed like a nun.

All of this is not even to mention the embezzling subplot in which Dee’s friend Mavis is framed for stealing the PTA proceeds and chased out of a malt shop by police officers.

The more I talk about Harper Valley PTA, the more amazed I am that it did such a good job with Dee.

…at least, it did at first. Dee being so much unlike her mother — regimented as opposed to free-spirited, studious as opposed to gossipy, restrained as opposed to unbridled — should have fueled both the film’s comedy and conflict. After all, making Dee more like the Harper Valley PTA than she is like Stella could have taken the story in a thousand different directions.

Instead (and it actually kind of hurts to write this) Dee becomes more like her mother, and that’s presented as a good thing. She gets her braces removed. Her mother treats her to a makeover. She gets a new wardrobe. Stella even tears up because her daughter isn’t frumpy anymore.

And while some lip service is paid to the fact that she’s still the same old Dee underneath the makeup, it’s only lip service and it’s insane to me that this isn’t challenged in any way.

It’s a bit like a hypothetical episode of The Simpsons in which Lisa is depressed, so her parents babe her up and buy her more flattering clothing and that’s presented as a genuine solution to her problem. It’s strange for the film not to have anything like an “I love you just the way you are” moment between Stella and Dee. Instead we have a “See? I told you you’d get prettier one day” moment, and it isn’t one played for laughs.

There’s even a scene early in the film in which Stella confides to Dee that she herself was once plain and therefore worthless, but she grew into sex personified, and so will Dee. The message here, deliberate or not, isn’t that it’s okay to be different; it’s that you shouldn’t worry if you’re different, because you might turn out to be hot at some point.

When Doris Day asked her mother if she’d be pretty one day, the woman sang back, “Que será, será, whatever will be will be.” When Dee asks her mother the same question, Stella Johnson replies, “Oh, you are going to be spitting dick out of your mouth day and night, I assure you.”

Harper Valley PTA tries to do far too much. The story needed to be fleshed out beyond the lyrics of the song, of course, but it seems almost like nobody making the movie could agree on how to do that.

It’s frustrating that it hits on a genuinely interesting story in Dee, but doesn’t seem committed to it and ends it on a sour note. It’s frustrating that it introduces cool-headed, big-hearted Willis into Stella’s life, but he never becomes the sobering influence she needs after she starts demolishing homes and distributing spycam pornography. It’s frustrating that a story about generational culture clash never gets more interesting than that extraordinarily vague premise itself.

But here’s the thing: it says something — perhaps quite a lot — that Harper Valley PTA gets to be frustrating at all.

I didn’t expect any movie based on a novelty song to have much to recommend it, but I can easily make a list of things I liked about Harper Valley PTA, and it would be longer than similar lists I could make for most movies.

Anyone going to see Harper Valley PTA in 1978 was going because they liked the song, and certainly anyone working on the movie knew that would be the case. They didn’t need to give their audience anything more than basic competency.

The fact that anything beyond basic competency shined through is practically miraculous. Somebody could take the key components of Harper Valley PTA and make a genuinely good film without having to discard or substantially change many of them.

It needs some tonal consistency. It needs better pacing. It needs to better understand the story it’s telling and be more aware of where it needs to go.

That’s not a complete overhaul; that’s a few extra drafts before shooting, and it represents the difference between this too-late, throwaway tie-in product and a film that people might actually remember and care about.

…or, failing that, they could have trimmed all of the serious stuff and just gone completely bonkers. That would have also worked. I think it’s clear which approach I would prefer, but the movie could succeed either way. It could be a droll social satire, or a thoroughly silly madcap farce.

But it can’t be both. Airport and Airplane! are both completely functional movies, but you can’t cut back and forth between them and expect it to work as a singular viewing experience.

There is a decent film buried here, but it occupies about 30 minutes of the runtime. I’d never, ever recommend it to another human being, but if you were forced to watch it you’d likely find bits to enjoy.

I know I didn’t have much to say about Barbara Eden, but she’s a fine Ms. Johnson. In looks alone I’m sure she fit the mental image fans of the song already had in mind, and her moments with Dee, Willis, and Alice all feel genuine. It’s when she morphs into Woody Woodpecker for the sitcom sequences that she flounders, and I can’t blame her. Maybe she couldn’t wrap her mind around the transition any more than I can.

But Barbara Eden did what she was paid to do. She looked a certain way, she brought a known degree of acting ability, and she was likeable enough to keep audiences on her side. It would be great to say that her performance here was revelatory, but it isn’t. Eden hits her marks and does the material the exact justice it deserves, neither elevating nor sinking it at any point.

The real crime is the complete waste of Susan Swift as Dee. This was her second film, and her performance was far and away the most impressive. She only did a handful of films after this — many of them TV movies — and then retired from acting.

Somewhere, in another universe, Susan Swift played the main character in a great coming-of-age film. Maybe it made her a star; maybe it didn’t.

But the kids out there who needed to see it learned a lot about who they were. They learned it was okay to be a little different. They learned there’s value in moderation. They learned that while it may be fun to gallivant around without a care in the world, somebody still has to keep that world from falling apart.

If you do end up having to watch Harper Valley PTA at some point — maybe in a fallout shelter that only contains six VHS tapes — watch her face. Watch her body language. Watch her performance.

There’s a character there that Susan Swift brought to life in spite of the script, in spite of the film, in spite of anything going on around her.

Watch her. Because that’s exactly where the real movie is buried.

Stella gets up in front of the town and tells them exactly what’s on her mind. That’s the movie we got to see.

Dee sits in silence, processing, mentally searching for her place in the world. That’s the movie I wish we could watch instead.