Well, we had to talk about it sooner or later…

In July 1991, Paul Reubens was arrested for indecent exposure. For a children’s entertainer, that’s understandably a death knell. But it was also — let’s be frank — kind of bullshit.

Reubens, as we all now know, was evidently pleasuring himself in an adult theater. Police raided the theater and made arrests as they saw fit. By Reubens’ account — which I find pretty believable — once they realized they had caught a celebrity, the police were not as interested in the rest of the culprits. They had Pee-wee Herman. Who else mattered?

Reubens — also by his account — volunteered to do charity work for children, in character, in exchange for keeping the arrest quiet. However seriously it might have been considered, that ultimately didn’t come to pass. Reubens’ mugshot was all over the news, and he became the butt of jokes for talk show hosts, standup comedians, and sketch comedy shows overnight.

Pee-wee’s Playhouse had already completed its run, which I didn’t realize as a kid. Reubens’ arrest made for exceptionally poor timing, because it was easy to conclude that CBS cancelled his show in response. In reality, they just stopped airing reruns. The net effect was the same, however; Pee-wee Herman was dead, and Reubens no longer had a career.

I’m making sure to talk about this, because it was one of the formative moments of my childhood.

When this happened, I was 10. I didn’t understand it, mainly because I had no concept of adult theaters or masturbation, let alone what that kind of social fallout would mean for a celebrity.

All I understood was that one week I could watch Pee-wee’s Playhouse, and the next week I couldn’t. It was over. Pee-wee wasn’t moving to a new show or a new movie or anything else. Pee-wee was gone. A character I loved — who gave me countless hours of joy and entertainment — was never coming back.

I wasn’t alone. Pee-wee meant a lot to many children at the time. Looking back, to be totally honest, I believe I owe a huge amount of my creativity — and my understanding of its importance, and my desire to nurture it in myself and others — to the shows I watched growing up that embraced and actively glorified the power of imagination.

I had Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood, with a whole Land of Make Believe. I had Muppet Babies, in which the toddlers had exciting adventures in exotic locales without ever leaving the nursery. I had Pee-wee’s Playhouse, in which even the most mundane things — a globe, a clock, a chair — were enthusiastic friends and companions.

Imagination mattered. Hell, according to those shows and so many others with which I was surrounded, imagination was everything. Take it away and…what are you really left with? A rich inner life was as important as — or more important than — anything we could desire externally. Imagination mattered. To me, possibly because I had it reinforced so deeply, so firmly, so repeatedly in my early years, it still does.

Reubens’ scandal came as a severe blow for that reason. Pee-wee’s Playhouse wasn’t just a show I liked to watch; it was part of who I was. The scandal represented a sharply, cruelly revoked promise. It was a reminder that we couldn’t be kids forever; that reality was going to intrude. And when it did, we wouldn’t like it. We would lose things that were important to us. There would be no going back.

I believe Reubens’ arrest marked the day a lot of children lost their innocence. It was a turning point. Something that had brought us so much joy was suddenly a source of embarrassment.

And yet, especially now, I can’t look back and make any more sense of it than I could then.

Sure, I understand that openly pleasuring one’s self in an adult theater would be considered public indecency. That in itself doesn’t bother me; I’ve never attended a pornographic film and I can’t imagine I ever will.

But, accepting that it is illegal, I don’t know why adult theaters are allowed to operate. Why else would somebody go? It doesn’t seem to me as though they serve any purpose other than providing a context for people to pleasure themselves or others…either case being illegal.

The police made an easy bust that day. Perhaps they had some quota to meet. Perhaps they just felt like being dicks. Certainly once they had Pee-wee Herman in handcuffs they felt like being dicks, focusing their attentions on him and actively deciding at some point that they’d prefer to ruin his career than keep it quiet. Instead of accepting an offer to make some needy kids happy, they turned the arrest into a spectacle that robbed kids across the country of happiness that was rightly theirs.

Reubens’ treatment may have been just, but it certainly wasn’t fair. Those who knew him — including his previous costars, such as Valeria Golino who played Gina in Big Top Pee-wee — spoke out against his treatment. Viewers and parents wrote tens of thousands of letters of support to one show (A Current Affair) that covered the scandal.

But it didn’t help. He was unnecessarily demonized, and his legacy was tarnished forever.

And that was it. For years, Reubens didn’t work.

He eventually started popping up here and there in small roles. I distinctly remember him showing up on Murphy Brown as one of Murphy’s secretaries. A running joke in the show was that the title character couldn’t keep a secretary, either due to their outlandish quirks or something she herself said or did, and each week we’d see a new one. Except for Reubens, whose particular secretary character stuck around.

I suspected that was Candice Bergen choosing to sacrifice one of her own show’s most famous jokes for the sake of giving her friend some steady work. I have no idea whether or not this is true, but it’s something I choose to believe.

Reubens himself was probably doing okay. I never heard about him going broke or being homeless or anything like that; it’s just that his future roles (and any royalties he expected from reruns of Pee-wee’s Playhouse) dried up overnight.

Maybe one day Reubens would be back, but Pee-wee surely wouldn’t.

And then…times changed.

People grew up.

Those making decisions about television shows and films were no longer the ones who turned their backs on Reubens. Rather, they were increasingly those who grew up watching Reubens, who felt that his treatment was uncalled for.

What’s more, the public perception of sexual indiscretion had changed. When a huge cache of hacked, private celebrity photos was released a few years back, how many of the victims faced any kind of fallout for the sudden publicity of their sex lives? There’s even a route to stardom seemingly available to those who knowingly leak their own sex tapes.

It’s not the career killer it once was. And 28 years after Big Top Pee-wee, we saw an official appearance by the character again. Not as a special guest, not as a cameo…but as the headlining star of his third film.

I have to admit, I never saw that coming.

Here’s what I saw coming even less: it was worth waiting for.

Pee-wee’s Big Holiday is, against all odds, a delight. An incredible late-game reemergence from a character that, by all rights, probably shouldn’t work as well as he still does. It’s funny. It’s sweet. It’s thoroughly charming. And I honestly couldn’t be happier with it.

Bringing characters and shows back from the dead is often a fool’s errand. It may well make money, but it very rarely pleases anyone who loved the original incarnations. Here you just have to look at my reviews of Project: ALF, Red Dwarf, or Arrested Development. Elsewhere you’ll hear endless (though probably well-deserved) griping about the Gilmore Girls revival, or the Sex and the City films. The various revivals of Futurama all have their detractors, and while I’m probably more forgiving of the show than most, I can see their point.

Something gets lost in the revival. Actors age. Or die, or are no longer available, or are not interested in returning. Writers very rarely return for various reasons, and are too often considered expendable, as nobody would visually notice they’re missing. Networks have new expectations that a revived production may not know how to meet while maintaining its earlier level of quality.

And, perhaps most frustrating of all, we change.

We get older. Our tastes evolve, and hopefully refine. Something that we once enjoyed a show for doing no longer interests us. If the revived show tries to do it again, we feel bored. If the revived show does something new, we complain that it doesn’t feel the same as what we remember.

We can reunite The Beatles, but we can’t make them write another “Hey Jude.” It’s a no-win situation.

Except, of course, for those glorious few that do manage a win.

Pee-wee’s Big Holiday is one of them. Nobody is more surprised by that than I am.

The film walks a line so fine it’s often difficult to believe it exists: a perfect balance between appealing to nostalgia and providing something new. In fact, I can probably count on one hand the number of revivals that manage it better than this film does.

Let’s not go nuts, of course; Pee-wee’s Big Holiday isn’t a great film. It is, however, a surprisingly good one, which merits celebration in its own right. And it does so much so well that it deserves to be studied as a kind of template for those looking to revive properties of their own.

For longtime fans, Pee-wee’s Big Holiday offers some cute little nods (Pee-wee’s hatred of snakes, a character referring to him as “rebel”), but they’re not barricades to the enjoyment of new audiences. It borrows the feel of previous Pee-wee outings — mainly Pee-wee’s Big Adventure — but doesn’t actually repeat jokes or setpieces.

When I say it mainly borrows from Pee-wee’s Big Adventure, I mean it. It’s another road movie. It’s about Pee-wee heading from some indeterminate location to a fixed destination (Texas there, New York here). Along the way he mixes it up with colorful characters and gets into and out of scrapes. The stakes are comically low (a missing bike there, a birthday party here).

I can’t blame Reubens for taking the character back to a formula that he knows worked. At the same time, though, it’s a worrying impulse, as it invites immediate and likely unflattering comparison. “So, he made Pee-wee’s Big Adventure again? Only worse?”

What rescues it is the fact that the material within that framework is entirely unique. Pee-wee doesn’t run afoul of a motorcycle gang, or get mistaken for making out with a woman in a big dinosaur, or sing folk songs with a boxcar hobo, nor does he experience direct equivalents of any of those things. America is a big place, and Pee-wee (via Reubens) takes the opportunity to see and have very different experiences on his second outing.

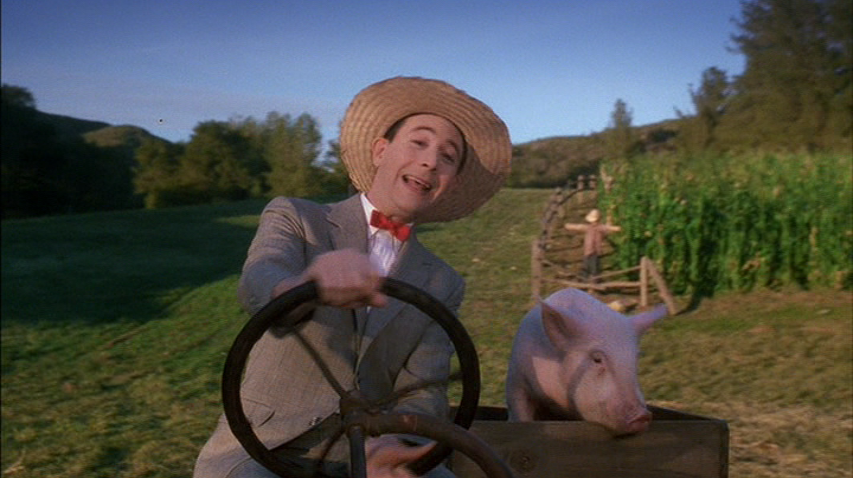

Of course, it’s not the second outing for this Pee-wee. Once again the character is an entirely new incarnation. This time, he’s a friendly chef at a diner in a small town he’s never left. In fact, we learn that the one time he tried to leave, he was involved in an accident that resulted in him needing a metal plate in his head. Since then, he’s never attempted to venture further than Fairville’s limits again.

Early in the film we get our equivalent of the breakfast machine from the first film, only this time spanning the town. Pee-wee wakes up, is launched from his bed, skiis down the roof, plops into a tiny car, and so forth.

And here it has its own kind of thematic resonance. In the first film it was a joyous, playful sequence that showed us just how many toys (of all kinds) Pee-wee had, and how much he relished just having them. This sequence, however, shows us how well Pee-wee knows his town. Where everything is, where everybody will be, how everyone and everything will react to him…so perfectly does he know this that he can turn his little corner of the world into its own Rube Goldberg machine. It’s one thing to be able to set one up in your living room, and another to know your surroundings so well that you can use them instead.

Pee-wee’s happy in Fairville. He’s comfortable. He’s secure. But he’s also, on some level, bored.

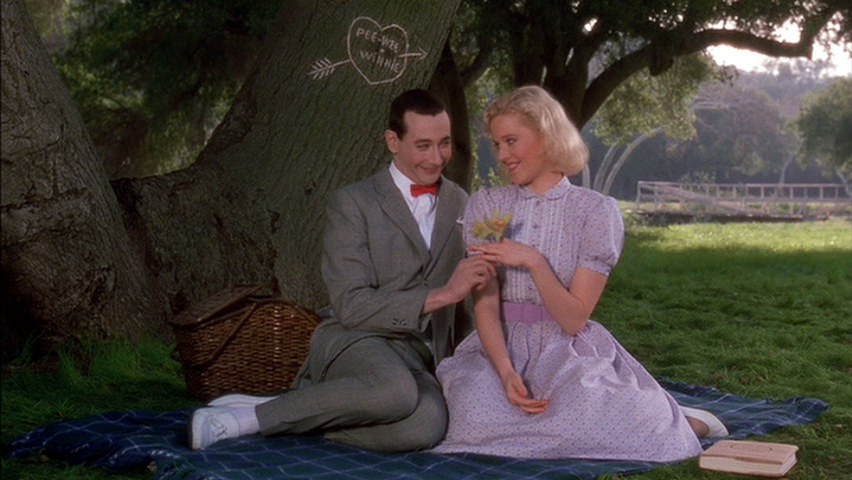

We don’t see it — at least not overtly — but it’s there. It’s even what drives the opening dream sequence, which is also probably the funniest moment of the film: we see Pee-wee bidding farewell to an alien friend. The alien invites him to come, but Pee-wee can’t. “I want to go,” he repeats almost tearfully, over and over, “but I can’t leave home.”

It’s a funny sequence if only because of how silly it is, and it’s also a pretty great opening feint. It makes sense as a dream sequence, but do we immediately assume it is one? We haven’t seen Pee-wee in almost thirty years, after all; why couldn’t he have made an alien friend in that time? One who departs just as we tune back in to see what’s going on?

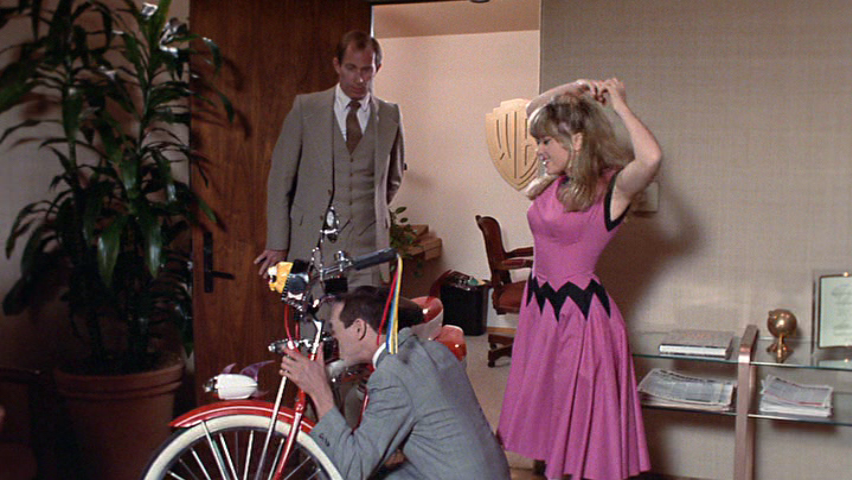

At work that day, he meets another new friend. Human, this time, but one who just as overtly suggests a world of adventure beyond the horizon. It’s Joe Manganiello, playing himself, and who immediately establishes himself in Pee-wee’s eyes as “triple cool.”

That much is believable. I mean, look at the guy. He’s pretty effortlessly awesome. He’s handsome. He’s famous. I think it would be pretty difficult to make a milkshake for that guy and not envy him.

But it’s not envy that we see here. What we see instead — surprising both of these guys as much as it surprises us — is camaraderie.

The two turn out to have a lot in common, which is a pretty hilarious conceit just from looking at a screengrab.

They both like stupid jokes and wordplay. They have a mutual favorite treat in rootbeer barrels. (Which they each drink with tiny straws.) They each just…get each other. And as comically unexpected as that is, it also turns out to be pretty believable.

I’d actually never seen Joe Manganiello in anything before this. Within the film he credits himself as having been in True Blood and Magic Mike, which…good for him, I guess. But I don’t think you need to recognize him in order to get the joke…the fact that this gorgeous, famous, swarthy hunk finds his soulmate in Pee-wee Herman.

The two of them bond — sincerely bond! — over Pee-wee’s detailed model of Fairville, and Manganiello feels bad that Pee-wee’s never left town. Never had an adventure. Never gotten a chance to grow up. In an offer that’s both narratively efficient and unexpectedly touching, Manganiello invites him to his upcoming birthday party in New York.

On one condition, of course: that he makes the trip by road, and not by air. “A few days on the open road is worth a lifetime in Fairville,” he says. “The way I see it, Pee-wee Herman, you’ve got a choice to make. Stick around here, or live a little.”

And we’re off. The film is officially in full swing, and it’s impossible to ignore how easily, how perfectly, how magically Reubens slips right back into the Pee-wee persona.

He looks and sounds incredible, as though 10 years at most have passed. I’m sure it’s some fancy makeup work, but seeing Reubens look so much like the Pee-wee we remember is almost like being rocketed backward in time. It’s like finding a Pee-wee movie from the height of his popularity that is only now being released. It’s like sliding back into childhood, and finding things exactly as you remember them.

Aging happens. I sure wish it didn’t, but every time I find a gray hair in my beard (or more hair in my drain) I’m reminded that it does. And there’d be no shame in Paul Reubens looking like an old man. But, at the same time, it’s kind of a relief that he doesn’t. There’s always something sad about someone looking 30 years older while trying to inhabit, without alteration, a character they played 30 years ago. Nobody wants to see an elderly Pee-wee shuffling slowly down the sidewalk; yes, actors age, but by that point we’d just rather not see him at all.

But this isn’t elderly Pee-wee; it’s just Pee-wee. We see it in every interaction. We hear it in every line. And we’re treated to it in the way he bounces off of every new character he meets along the way. And, thankfully, those characters feel more like they belong in Pee-wee’s Big Adventure than they do in Big Top Pee-wee. They feel lived-in. They feel unique. They feel, largely, welcome.

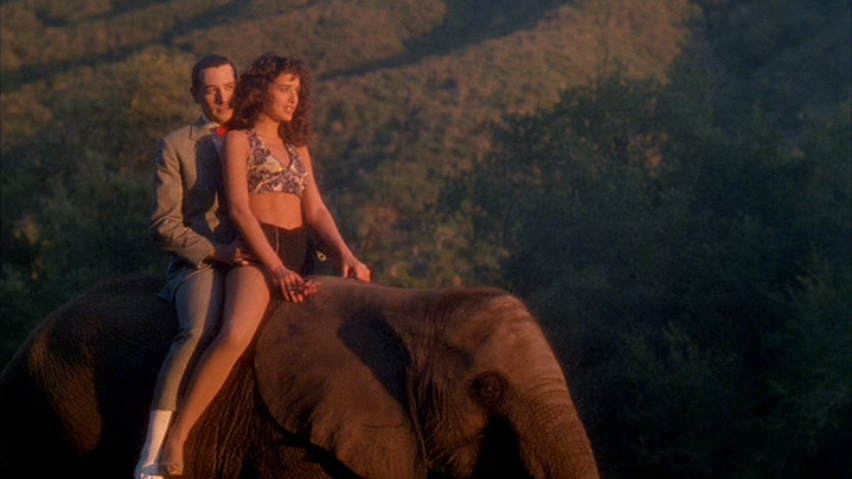

The first companions he picks up are a trio of bank-robbers, among them the great Alia Shawkat, but all three of these actresses are fantastic. They play the crooks as the kind of hard-nosed young criminals you’d find in 1950s scare propaganda, warning parents about the dangers of letting their kids mingle with the wrong crowd. All of which is to say that they’re treated as menacing while coming off to viewers as quaintly adorable. (As is Pee-wee’s question after he picks them up. “Why are the cops after us? Are you guys witches?”)

From there Pee-wee drifts gradually eastward, not entirely convinced he’ll make it in time for Manganiello’s party. Like the quest for the bike, however, and completely in line with Manganiello’s advice in this film, the journey is the destination. And it’s a lot of fun.

Highlights are plentiful throughout. I especially loved Pee-wee’s visit to a Snake Farm…which is actually just a South of the Border-style tourist trap that sells tchotchkes and creates visual gags as opposed to housing actual snakes. A box of baby rattlers is really, for example, a box of baby rattles.

It’s an amusing subversion of expectations, made all the better by Pee-wee’s stubborn refusal to engage in any of the fun, despite the fact that dumb visual gags and wordplay are right up his alley. He’s simply unwilling to play along due to his repulsion to snakes, which is so strong he’s repulsed even by the idea of joking about snakes. It works on a few levels, and it’s very funny to see Pee-wee being the stick in the mud.

There’s even a great scene in which Pee-wee reenacts the classic scenario of the farmer’s daughter…only there are nine of them, and they literally descend on his room from all angles with — it has to be said — impeccable comic timing. After Big Top Pee-wee‘s idiotic romantic dalliances I expected this sequence to be far more problematic and infinitely less funny than it actually was.

Other scenes see him hitching a ride in one of the only flying cars in the world, piloted by Diane Salinger, who played Simone in Pee-wee’s Big Adventure. Then there’s the scene in Amish Country, in which Pee-wee slowly deflates a noisy balloon, which is easily one of the most successful examples of endurance humor I’ve ever seen.

It’s far funnier than it has any right to be, and its button (in which the Amish children are all excitedly deflating balloons of their own) is kind of wonderful. It’s nice that Pee-wee doesn’t annoy these peaceful, gentle people; the easy joke would be to have them turn and chase him out of town. Instead, they embrace him. Just as everyone else does.

I think that was one of my complaints about Big Top Pee-wee. Outside of the circus, everyone hated him. Wherever he went, people were condescending and rude. They treated him like an outcast…which sort of defeats the entire joke of the character. In Pee-wee’s Big Adventure he was never treated that way, in spite of how incongruous he was in every situation. They just treated him like a person. Big Top Pee-wee‘s cast wanted him drawn and quartered, and that just wasn’t as much fun to watch. It was made even less fun by the fact that it was never resolved; they didn’t come around to loving him…they just ate magic weenies and shrunk.

Pee-wee’s Big Holiday sees people falling in love with Pee-wee wherever he goes. From the Amish to doorbell heiresses to Joe Manganiello. People like him, and that makes the movie more fun to spend time with. In fact, rewatching it for this review, I was struck by just how comforting the entire thing was. Nobody’s at each other’s throats; everybody’s just plugging along, hoping for the best, having fun whenever and wherever they can find it.

One of the characters Pee-wee hitches a ride with sells little joke items, such as a fake grocery bag to stick to the roof of your car. In reality, traveling around from business to business trying to sell junk like that would be a miserable existence. In Pee-wee’s Big Holiday, the guy is having a blast, loving life, not at all struggling for dollars the way we’d expect.

It’s a film in which there’s really nothing to worry about, but so much to enjoy. It’s a film in which the only tension is whether or not Pee-wee will see his new friend again…but we know that, even if he doesn’t, he’s making dozens of new ones along the way. It’s a film in which we’re never asked to invest in the journey, but always welcome to take pleasure in it.

And, you know what? I kind of love it.

If I made a list of the films that are the most important to me, Pee-wee’s Big Holiday obviously wouldn’t come anywhere near it. But if I made a list of the films I most enjoyed spending time with…well…

The soundtrack isn’t composed by Danny Elfman this time around, but rather by Mark Mothersbaugh, who really was the next best choice. He also has a perfect ear for Pee-wee’s antics, so while his work here isn’t nearly as memorable or iconic as Elfman’s was for Pee-wee’s Big Adventure, it’s perfectly fitting and often brilliant. This is especially true toward the end of the film with a song that apes “New York, New York” from On the Town, sung by Pee-wee and Manganiello, their characters seeming to be just barely familiar with the source material.

It’s quite funny and a fittingly entertaining build to the climax, giving Pee-wee a chance to experience the Big Apple without having to spend too much time there (and thus upsetting the journey/destination ratio of the film). Pee-wee gets to visit Grand Central Station, shop for souvenirs, eat his first slice of pizza, and even see the Statue of Liberty!

Well, a Statue of Liberty.

It all builds to Pee-wee making it to Joe Manganiello’s building just in time for the party…except he falls through an open manhole and misses the whole thing.

That’s fine, of course. Pee-wee stuck in a sewer isn’t nearly as interesting as the rest of a film in which he trots from state to state with eccentric characters (GO FIGURE), but it provides an important reveal: as time ticks by and Pee-wee fails to show up, Manganiello starts to worry. He really did like the guy. So much so that not having Pee-wee at his party is heartbreaking to him.

As much as Pee-wee (rightly) saw in Manganiello, Manganiello saw even more in Pee-wee. He cared about him, and now he worries about him and his safety. He tried to send Pee-wee on a big adventure, but what if the guy got hurt? What if he just decided not to come? What if Manganiello didn’t mean as much to Pee-wee as Pee-wee meant to him?

It’s funny and effective. And, of course, Manganiello finds out about Pee-wee’s plight and fires a grappling cannon right to scene of the tragedy to pull Pee-wee out himself.

And, really, that’s the heart of the film, and it’s also why this film stands distinct from Pee-wee’s Big Adventure. In that movie, Pee-wee himself learned very little. He was selfish and he wanted his bike back. So…he got his bike back. Sure, at the end it’s suggested that he’s a little more open to Dottie, and that’s nice, but it’s still only a suggestion, and it’s not a defining aspect of his journey.

Here, though, the journey is one of friendship. It’s one of honest and genuine connection between two men. It’s the most romantic platonic story I think I’ve ever seen, which is probably why it’s also so funny. The connection between Pee-wee and Manganiello is one of legitimate beauty…two simple people who find just what they need in each other, each of whom worries that it was only a fleeting fancy.

But, in the end, they reunite. And it’s not Pee-wee getting a bike back…it’s two lonely people finding someone, at last, who understands. For adults, that’s a nice, unchallenging bit of comedy. For kids, it’s an important lesson.

No matter who you are, what you look like, how you act, how isolated you may feel…you’re not alone. It may take you some time, but you can meet that person. Whoever it is. And when you do, you’ll do whatever you can to keep them.

Pee-wee’s Big Holiday is a film that absolutely warranted a return of the character. It’s also, however, a sad reminder of what we’ve missed.

Reubens’ conviction wasn’t just the end of a career…it was the effective and untimely death of a beloved character. One who appealed to children and to adults in fairly equal measure. One who had so many more adventures to go on…so much more of the world to see…so many more people to entertain.

Big Top Pee-wee made a fairly convincing argument that there wasn’t much left to see, but Pee-wee’s Big Holiday establishes that film as the fluke. This is what we could have had. Here and there, bit by bit, Pee-wee could have been doing his thing. Making us laugh. Handing down passive life lessons. Reminding us that we are all, in our own ways, outcasts, and that it’s up to us to surround ourselves with people who won’t make us feel that way.

I don’t know if Reubens will make another Pee-wee film. If he does, I’ll watch it. And if he doesn’t…at least I know that Pee-wee never really goes away.

He’s just existing in some other incarnation. One we might not be able to see…but wherever he is…whatever he’s up to…we know he’s still worth watching.