The heat doesn’t get to me, but I know it takes a toll on the other buyers.

I’m going to use it to my advantage.

There’s probably no more tiresome criticism of reality television than the parroted claim that “it isn’t real.” It’s a meaningless comment that misses the point entirely. The Simpsons aren’t real either, nor were the group of friends who hung around Central Perk, nor were those wisecracking doctors in the Korean War. Ultimately, none of that matters. The aim of any television show — of any kind, in any genre, from any time period — is singular: to entertain enough people that it remains profitable. You’ll fool only yourself if you try to think otherwise.

Of course the difference between reality shows and my other examples above is that reality shows are populated with people rather than characters. Right? In Storage Wars professional pest Dave Hester is a man who really exists, of the same name, who really does buy storage lockers for a living. He’s not played by Dan Castellaneta or Matthew Perry or Alan Alda. He’s a real person you can find actually doing this in real life.

Here’s the big secret, though: that doesn’t matter.

Dave Hester — or any “character” from any reality show of your choice — may well exist. But that does not separate him as solidly from any openly fictional creation as one might think. In both cases, whether you’re a yellow-skinned cartoon dad or flesh-and-blood human being who is filmed as you go about your business, you fill the same role: you’re a character in a TV show that wants to keep viewers entertained.

Which is why the argument that reality shows “aren’t real” is meaningless. They don’t want to be real, no matter what they may say. They want to be profitable. They want to be watched. “Reality” is low on the list of things to strive for when assembling any given episode. Maybe you feel the Duck Dynasty guys play it up to the camera, while Intervention features real people with real problems. You’re allowed to feel both of those things, but ultimately those are just two different paths that two different shows have chosen to follow in order to achieve the same thing: profitability.

Perhaps you’d fault a “reality show” for using scripted segments and set pieces, but ultimately they’re doing it for you. After all, if they didn’t have their dramatic moments, quick zingers and narrative flow, would you still be watching?

Perhaps you’d fault a “reality show” for using scripted segments and set pieces, but ultimately they’re doing it for you. After all, if they didn’t have their dramatic moments, quick zingers and narrative flow, would you still be watching?

It’s the narrative flow that I’m really going to dig into here, because that’s why “reality programming” can never be real. And that’s okay.

Think about your own life. Think about what you’ve accomplished, what you’ve failed to accomplish, the relationships you’ve had, the jobs you’ve held, and the people whose lives you’ve affected. There might be a good story in there, somewhere.

Now think about all of the meals you’ve eaten, the days you’ve spent sick in bed, the time you’ve lost in traffic jams, the numberless uneventful trips to the supermarket, and all the weekend afternoons you spent scrubbing the bathroom floor.

What I’m getting at is this: your life, anyone’s life, real life, is a combination of components from these two categories. You have the important stuff on one side, and the unavoidable but ultimately meaningless stuff on the other. And — fun fact — the meaningless stuff will always and must always outweigh the important stuff, in a quantitative sense.

This prevents real life from ever making a good story. There isn’t narrative flow. You’re always stuck with the boring parts; there’s no skipping them. Bad things happen to good people and they just happen. There isn’t a reason for most of the things you’ll experience…no mustache twirling villain lobbing obstacles in your way, no ultimate goal that you’ll need to achieve. Reality isn’t a story; it really is just a bunch of stuff that happens.

Which is why it’s okay that reality shows “aren’t real.” Of course they’re not. If they were, we’d see people sit around awkwardly in real time for 22 minutes trying to make stilted conversation. Reality shows shouldn’t do that. That’s not fun, that’s not watchable, and that’s certainly not profitable. Nobody wins, and if you really wanted to see “reality” when turning on the television you should probably have turned your head to look out the window instead.

No, in order for reality to become a story, it needs to be edited. Finessed into a more cohesive statement. Trimmed of its dull parts and with its stronger moments emphasized. Think about your life again, but this time don’t think about all the mundane aspects. Concentrate, maybe, on an important relationship you’ve had, or a time you stood up for something that was right, or a seemingly insurmountable difficulty that you overcame. Only focus on the moments that contributed to this eventual triumph, and — this is important — stop thinking of anything at all that might have happened after your moment of success. Through the magic of editing, now you’ve got a story.

No, in order for reality to become a story, it needs to be edited. Finessed into a more cohesive statement. Trimmed of its dull parts and with its stronger moments emphasized. Think about your life again, but this time don’t think about all the mundane aspects. Concentrate, maybe, on an important relationship you’ve had, or a time you stood up for something that was right, or a seemingly insurmountable difficulty that you overcame. Only focus on the moments that contributed to this eventual triumph, and — this is important — stop thinking of anything at all that might have happened after your moment of success. Through the magic of editing, now you’ve got a story.

I like Storage Wars. I think it’s a good show, and if you asked me why I’d probably say something about the characters, or about the interesting items that they find. Ultimately, though, I’m fully aware of the fact that every episode is “assembled,” and on some level what I’m really responding to is the reliability of the structure. This isn’t found footage presented in the raw; this is a formula decided upon by producers and editors so that every episode, even in a show about people who buy storage lockers and hope for the best, follows a clear narrative.

First we see all of the main characters arrive at the location for the day, then they exchange pleasantries. Then we watch some bidding. Once everyone who’s going to get a locker has one, we get to watch them rummage around looking for a rare or expensive item to show off. Later on the group splinters off to have their finds appraised, and we close with a scorecard showing how much money each bidder made.

It’s simple, but it can afford to be simple. We need only the barest sketch of a narrative upon which to hang our attention, but we do need one. I don’t think the show would be impenetrable if, for instance, we cut back and forth between different auctions on different days, or followed one bidder all the way through the process before starting over with another, but I do think it would look messy and be needlessly confusing. The format provides structure, and it also provides a kind of security…both for us, as viewers, and for those who appear in the show. Everybody knows where they are.

Storage Wars until recently featured four main bidding groups: Barry Weiss, Darrell Sheets and his son Brandon, Jarrod Schulz and his wife Brandi, and Dave Hester who is no longer on the show. Sometimes we’d get appearances from other bidders as well, but that was the main cast that you could expect to see in any given episode.

What’s interesting about “The Yup Stops Here,” though, is that it feels just different enough not to be mistaken for any given episode. It features the same bidders listed above, and it’s presented in the same format outlined above as well. But when assembling this particular narrative, the editors took an interesting approach.

What’s interesting about “The Yup Stops Here,” though, is that it feels just different enough not to be mistaken for any given episode. It features the same bidders listed above, and it’s presented in the same format outlined above as well. But when assembling this particular narrative, the editors took an interesting approach.

We typically get captions telling us where the episode takes place, or subtitling whispered dialogue, but this time around we get something more: we get a time stamp. More importantly, we also get a temperature reading.

As an editor of a show like this, you are massively beholden to the footage you have.* It’s nice to think that an episode can be magically whipped up depending upon editorial whims on any given day, but if you don’t have romantic footage you can’t create a love story, and if you don’t have footage of two people fighting you can’t make such a conflict the centerpiece of your episode. When you do have small moments like that you can of course emphasize them and mislead your viewers into believing them to be more significant events than they actually were, but you need something to work with first. It’s editing, not alchemy.

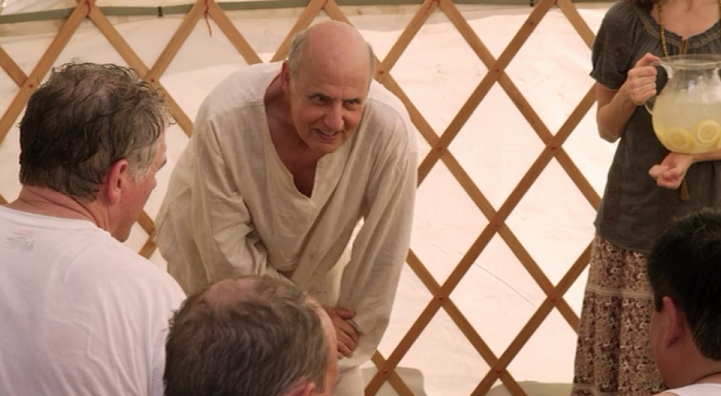

In this episode, the editors seem to have taken their cue from a comment made by Dave Hester on his way to the auction. He talks about how hot it’s going to be today, and how he’s going to use the heat to irritate his fellow bidders. This way, he says, they will become flustered, make silly mistakes, and overpay.

It’s a threat, and the editors are able to see from the footage that follows that he does see it through, so — just like that — “The Yup Stops Here” has its framing device: the heat.

It’s a threat, and the editors are able to see from the footage that follows that he does see it through, so — just like that — “The Yup Stops Here” has its framing device: the heat.

What’s more, there are 25 lockers up for bid today. We don’t know if this is an exceptionally high number, but we do know that the episode at least pretends that it is, drawing attention to how long the bidders have been standing around, how much hotter it’s gotten as the day progressed, and including quick snippets of auctions ending in order to emphasize the tedium of the day.

Typically we don’t see anything like this. One very obvious editing choice for the show is that we only see the auctions that result in a win for Dave, Barry, Jarrod or Darrell; if it’s won by any of the nameless bidders in the crowd around them, it simply gets cut.

At least, it usually does. By including other wins — even in the form of quick cuts — “The Yup Stops Here” is giving us a more realistic look at what a day of bidding on units must be like. There’s a lot of standing around in the sun, growing irritable and uncomfortable as the day gets hotter, watching other people walk off with the items you wanted. The curtain is pulled back, just enough, and it’s pulled back for a reason: Dave’s threat. After all, it wouldn’t mean much if the day was over in 22 minutes. What we need to see is an entire, grueling afternoon, so we know what Dave’s talking about when he says he’s going to take advantage.

The episode is no longer than any other, but this small tweak to the format makes it play out like Storage Wars: The Movie. As fans of any show know, a change in format makes you pay attention that much more; it keeps you on edge, and you remain fixed to the action because…well, if they bothered to change the format, they must have done so for a reason. So whether it’s Archie locked in the basement, Walt and Jesse chasing a fly or a demon that makes all the characters communicate in song, we watch more closely, because we know the show’s getting at something.

Here, the show is getting at the consequences of Dave’s threat. Never before have the actual items found or the money earned felt less important…what we have here is admitted psychological torture administered by the show’s closest thing to a villain.

Dave Hester is an interesting case. He left Storage Wars after season three, alleging various strange things about the show. His main complaint was that producers stuffed lockers with the items we see on television; it wasn’t really found by the bidders as we see at home. He complained that since it’s illegal to fix game shows, the producers of Storage Wars were breaking the law.

This is a claim worth debunking in several ways. For starters, planting literally millions of dollars of priceless antiques in storage units defeats the entire purpose of reality programming; it’s a genre that exists so that lots of episodes can be made quickly and cheaply. Secondly, it’s interesting that Dave incorrectly identifies Storage Wars as a game show, because the conventions of that genre are entirely different from the one in which he actually appears, and it’s possible that because he saw himself as a game show champion, he never realized that he was actually a reality show villain.

This is a claim worth debunking in several ways. For starters, planting literally millions of dollars of priceless antiques in storage units defeats the entire purpose of reality programming; it’s a genre that exists so that lots of episodes can be made quickly and cheaply. Secondly, it’s interesting that Dave incorrectly identifies Storage Wars as a game show, because the conventions of that genre are entirely different from the one in which he actually appears, and it’s possible that because he saw himself as a game show champion, he never realized that he was actually a reality show villain.

In this episode he pushes back against his fellow bidders aggressively. When Barry — an older gentleman who definitely knows how to work the cameras, the crowd and the audience at home — shows interest in a locker, Dave keeps bidding higher and higher just so Barry will have to pay more. He makes no secret of this, and eventually stops bidding on the sarcastic pretext that he didn’t realize Barry wanted it; he’d never stand in his good friend’s way.

It’s just the first missile he fires in the heat, and it’s his only successful one. As if in response to Dave’s claim that the show is “fixed,” this episode seems dead set on following everything he does to his fellow bidders in order to throw them off their game…up to and including a verbal confrontation with Darrell’s son Brandon.**

What happens on screen is every bit as uncomfortable as any high school scuffle you might have witnessed in real life…with the exception of the fact that Dave Hester, who appears to be in his late 40s, is sparring with a much fitter man in his early 20s. While Dave wants to appear in control and intimidating, he actually comes off as rather pathetic, and the discomfort in the crowd around him is palpable. At one point he mentions the fact that Darrell is standing between them is the only reason he’s not in an actual fistfight, which gives Darrell the funniest moment in the episode as he casually strolls away and observes, “Brandon’ll kill him.”

But no punches are thrown. The cameras are there. Far from inventing drama, the cameras here absolutely quell it, as both parties — as upset and heat-crazed as they are — know better than to assault another human being while being filmed for television. And as Brandon walks away — taking with him the title of Bigger Man — there’s a little bit of inevitable disappointment that Dave didn’t get punched. After all, he’s the bad guy. But that’s okay…we still have half the episode left…and narrative convention tells us he’s primed for a fall.

The heat goes on, the lockers go by, and the bidders are tired and frustrated. Barry finds himself in the same situation that Dave was in before: he knows Dave wants a unit, and he intends to make him pay more for it, just to get even. He pulls this off successfully, and is clearly happy about it, but Dave won’t admit defeat. He takes Barry over to the locker and tells him that it was Barry’s loss…there’s a 125 year old couch in the unit and it’s going to make Dave a fortune.

The heat goes on, the lockers go by, and the bidders are tired and frustrated. Barry finds himself in the same situation that Dave was in before: he knows Dave wants a unit, and he intends to make him pay more for it, just to get even. He pulls this off successfully, and is clearly happy about it, but Dave won’t admit defeat. He takes Barry over to the locker and tells him that it was Barry’s loss…there’s a 125 year old couch in the unit and it’s going to make Dave a fortune.

Barry’s response is something I’ll always be able to point to as evidence that the show — at least in its bidding portions — is real. He makes Dave a hasty bet of $5,000 that he’s wrong.

This isn’t a Mitt Romney style moment of misjudgment…this is an exasperated man who is tired of being pushed around in the heat by someone who cannot accept defeat. He doesn’t bet Dave $5,000 to be funny, to be cute, or to look cool on camera. He bets Dave $5,000 because Dave is wrong, Barry knows he’s wrong, and he’s had enough that he’s going to go out of his way to make him look like an ass.

Barry’s the anti-Dave in practically every way. He’s playful, with a natural charm and a genuine quick wit. He’s friendly, and though he does get caught up in the same bidding-up game that everyone does on this show, he never initiates it. He admits defeat regularly, and seems to just want to have a good time. We see this silver-haired guy with the silly skeleton gloves and the restless desire to make people laugh, and we like him.

Dave is aggressive. He pushes people, and relishes the fact that the cameras don’t let them push back. He’s a bully, and doesn’t really seem to have much fun. Whenever the show employs an obviously-scripted talking head featuring one of the bidders making a bad pun about something they found in the locker, Dave is noticeably absent. He doesn’t record lines like that. There’s a certain honor in that decision, but there’s a much larger stubbornness, and it’s not attractive in a character.

The $5,000 bet turns Dave’s threat right around on him. Yes, Dave did indeed needle his opponents in the sweltering heat until they cracked…but when they cracked, they took it out on him. They didn’t make silly mistakes; instead they came at him with knives out. He physically threatens a boy half his age, doesn’t think enough to walk away from the fight, tricks his fellow bidders into paying more than they can afford on lockers he knows are full of junk, and needles the nicest guy on the show into making him a $5,000 bet just to shut him up.

The $5,000 bet turns Dave’s threat right around on him. Yes, Dave did indeed needle his opponents in the sweltering heat until they cracked…but when they cracked, they took it out on him. They didn’t make silly mistakes; instead they came at him with knives out. He physically threatens a boy half his age, doesn’t think enough to walk away from the fight, tricks his fellow bidders into paying more than they can afford on lockers he knows are full of junk, and needles the nicest guy on the show into making him a $5,000 bet just to shut him up.

Barry ultimately wins the bet as an appraiser confirms that the couch is nowhere near that old, and when he does Dave storms off, leaving Barry and the appraiser behind, saying with his back to the camera that they can keep the couch. And when this happens, especially as it’s followed by the episode’s score card touting Barry as the winner and Dave $5,000 in the hole, it really does feel like the triumph of good over evil.

But that’s because it’s a TV show. And maybe this stuff actually happened, but that’s not what matters. What matters is that somewhere in an editing booth, people took real words and real moments and real confrontations, and turned them into an engaging piece of television.

Does “The Yup Stops Here” accurately represent what happened that day? I don’t care. The events are being sculpted in a way that takes what was probably just a miserable day bidding on storage lockers, and turns it into a sharp and insightful character piece, with quiet meditations on manhood, hubris and friendship thrown in for good measure.

They took actual footage of real people going about their day, and turned it into an engrossing, effective work of art. Is that misleading? That’s not the word I’d use. I’d call it impressive.

Reality TV isn’t real. It’s not supposed to be. It’s just supposed to be entertaining, and that’s enough for me.

——

* As if to illustrate this point, during the Dave and Brandon squabble we get a couple of seconds of people’s ankles, presumably because the camera simply wasn’t there to catch what was being said.

** The episode’s title is a telling stab at him as well, as it effectively uses Dave’s “Yup!” catchphrase against him…and, sure enough, after this season the yup did stop.