Last year, I started working my way through Roseanne for no real reason except that I remember enjoying it quite a lot as a kid. My memory of the show sure as heck got a lot of the details wrong, but I was right about the quality.

The writing was sharp. The casting was perfect. The acting was top notch. It was far more serialized than I remembered. Rewatching Roseanne made for a really fantastic revisit.

But ah, the sickle!

However much I was enjoying the show — including an awful lot of episodes I was seeing for the first time — there was always a grim specter on the horizon: season nine.

To provide context, prior to the recent Roseanne revival, season nine was the show’s final stretch, and it has a dire reputation.

It involves the Conners winning the lottery, which sounds like the sort of thing that could indeed be handled in any number of creative, intelligent, funny ways. Instead, B-list celebrities like Jim Varney, Tammy Faye Bakker, Jim J. Bullock, and Steven Seagal are trotted out to play exaggerated cartoons as the Conners themselves largely splinter off on joyless solo adventures and engage in limp parodies.

I remember people complaining about how awful it was while it aired, which suggests that widescale dismissal wasn’t a conclusion we culturally reached only after consideration and reflection. My friends who still watched the show at that point all reported back about how much they hated it. Later, I worked with someone who adored Roseanne, and we exchanged fond memories of the show…but when season nine came up, she grumbled about “the lottery season,” which seemed to say it all. Even in this largely positive (and very good) Facebook fan group, season nine draws a lot of unexpectedly strong ire.

Needless to say, I was very excited to finally get to see those episodes for myself. I love garbage!

And, well…it really is garbage. Its hideous reputation is well deserved. The entire time I was watching earlier seasons, I refused to believe season nine could be quite as bad as everyone said. How could one of television’s best shows tumble so far so fast that it immediately became one of the worst? Even The Simpsons represented a gradual decline…how could Roseanne represent a plummet?

I could write a few thousand words about how awful it is, but you can probably find those elsewhere. Or you can watch it yourself, preferably after watching any number of the previous eight seasons so you can wonder what the hell happened, too.

Instead of tearing down something people love, I’m going to do something far less common on this site: I’m going to build up something people hate. I’m going to celebrate some of the things this truly terrible season of television did right. Because, hey, it really did do some things right. And after the nearly flawless eight-season stretch that preceded it…I think Roseanne deserves that.

This is my list of the 10 things I liked about Roseanne‘s final season. I’d say “Top 10,” but, frankly, I had to stretch slightly to even hit 10 so I think we can call this exhaustive.

I did set myself one rule: no “I liked that X didn’t happen” entries. This list is exclusively about things I actively enjoyed about the season, so I can’t say things like, “Tom Arnold didn’t make an appearance.” Or “Watching the show didn’t give me a brain tumor.”

Here we go.

10) The theme song’s lyrics

…alright, I had to reach slightly for this one. I don’t dislike the lyric-version of the theme song, which debuted for season nine. Having said that…I also don’t quite see the purpose. Roseanne‘s instrumental theme tune was (and remains) iconic. This is a bit like having somebody warble over the Hawaii Five-O intro; even if it’s good warbling, why mess with something that’s already great?

Surprisingly, though, this version of the theme song isn’t bad, and the lyrics actually feel like they fit and weren’t crammed into an existing melody almost a decade after everyone got to know it. The credit for that belongs to John Popper, who wrote and performed this version of the song with his band, Blues Traveler. (Blues Traveler was one of the first bands I saw live. NOW YOU KNOW THAT.) They also recorded new stings to play between scene and act breaks.

I feel a bit bad for Popper that his version of the theme is associated with this of all possible seasons, but that’s just the way the chips fell. Popper appeared in season eight’s “Of Mice and Dan” as blues musician Stingray Wilson, backed, of course, by the rest of Blues Traveler. It’s not one of my favorite episodes, but there was obviously some mutual respect between the band and the show, as Popper was invited to compose theme song lyrics (one hell of an unexpected honor) and DJ hung a Blues Traveler poster in his room for the rest of the show’s run.

Of course, the less we think about Blues Traveler and Stingray Wilson existing in the same universe the better, especially since we learn that “Run-Around” and “Hook” — actual Blues Traveler hits in our universe — were written by Stingray Wilson on Roseanne…no. No. We have nine more entries. WE WILL STAY POSITIVE.

9) The Christmas episode

Roseanne is understandably known for having great Halloween episodes. Personally, too many of them break reality for my taste, but I can see why they have their following.

The holidays I really thought Roseanne nailed were Thanksgiving and Christmas. Thanksgiving episodes were more or less a gimme. As the extended family gathered in the Conner kitchen, we in the audience were guaranteed to see conflicts addressed, grievances raised, and great dialogue spread among a larger number of characters. A simple template, almost guaranteed to produce a memorable episode.

The Christmas episodes, though, were a bit less predictable. Maybe Roseanne needed some extra money and became a mall Santa. Maybe Dan took the opportunity decorating the house to bond with Becky’s brash new husband Mark. Maybe we get a peek at David’s abusive home life. Hell, maybe we give our Christmas episode over to Leon’s gay wedding.

I liked all of the Christmas episodes. I looked forward to them. And so I was genuinely worried when I saw that season nine had one as well. Was this godforsaken season really going to break the show’s perfect record with Christmas?

Actually, no. It wasn’t. “Home for the Holidays” is far from the best Conner Christmas, but it’s still pretty good. It’s the rare season nine episode that plays better in retrospect, too, as Dan’s periodic detachment from the celebrations makes a very sad sense when we later find out why. See, Dan (like John Goodman) was absent from a long stretch of episodes, the character spending some time in California. Unknown to anyone else, he was also canoodling with another woman. Christmas represents his return to the family. He’s plagued by guilt. He has doubts about both halves of the equation. Does he really want that other woman? Does the fact that he’s even questioning mean he doesn’t want his family?

Especially heartbreaking is the gift Roseanne gives him: the burning of their mortgage, which she has paid off. After all these years together, the Conners finally own their home. Dan is devastated, and forced to account internally for the damage he’s done to his family when they should have been getting stronger. This is all something we only find out later, and it works perfectly.

Except, you know, we find out this whole thing never really happened and Dan never actually cheated and Roseanne never actually paid off the house so really there’s no point to any of this and whatever retroactive emotion we link to the scene means we have to ignore the later revelation that undoes this one but no. No. We have eight more entries. WE WILL STAY POSITIVE.

8) Dan’s ennui

So why was Dan away from his family for much of the start of season nine? A very good reason, actually. In season six’s “Lies My Father Told Me,” Dan learns that his largely absent mother is mentally ill. It’s a secret Dan’s father kept from him for many years. In season nine, after the Conners hit the lottery, Dan realizes that he has enough money to get his mother the help she needs, and takes her to an institution in California.

This is a nice development, even if it’s only to give Goodman an in-universe reason to take a few weeks off from the show.

What’s nicer, though, is that this isn’t a snap decision, or something that happens between episodes. Instead, in “Honor Thy Mother,” we see Dan building toward the idea, beginning with a very believable, general sense of malaise and ennui.

Dan has money now.

For eight seasons, he’s struggled to put food on the table. Sometimes he’s failed even to do that. He worked constantly and regularly for whatever someone was willing to pay. “Dan the Drywall Man” had a reputation for doing good work, but that reputation never got him far enough to take it easy. Yesterday’s paycheck won’t last through today…he needs to get back out there and find more work.

Until now. Now he has money. Now he doesn’t even need a job, let alone a series of jobs.

And for perhaps the first time ever, his mind has a chance to wander. He begins to question his purpose. He wonders who he is, and what he’s doing. He opens up to characters he usually wouldn’t, such as Leon, in the vague hope that somebody can give him guidance. Having the luxury to reflect on meaning can be a curse, because it may lead to you suspect there is none.

Ultimately, Dan decides to help his mother, which suggests that this mental listlessness had a positive outcome. But it’s in the course of helping her that he meets and falls for her nurse. The same aimless, desperate thoughts that led him to make one of the least selfish decisions of his life led him also to make one of the most.

It was a plot development born of logistical necessity, but like so few other things in season nine, it worked.

7) A few of the premises

Season nine was rife with idiotic premises. Does anybody really care if Jackie dates a Moldavian prince? Did anybody need to see the Conners go to Martha’s Vineyard so they could stand silently around while a bunch of nobodies told jokes about being rich? Was there any reason at all to embed a jokeless, condensed version of Rosemary’s Baby in the middle of an Absolutely Fabulous crossover?

And did I really just manage to list a bunch of shoddy premises without even mentioning the time Roseanne fought terrorists on a hijacked train? Jesus.

The season was full of terrible ideas, but there were a few genuinely good ones.

Roseanne and Jackie spending an entire episode at a spa together should have been great, and in any previous season we would have certainly gotten some great dialogue as the two worked through their problems, gave each other advice, reminisced, fought and reconciled…it, frankly, would have been amazing. Roseanne and Jackie had perhaps the most rewarding dynamic on a show full of rewarding dynamics, but season nine just has them get yelled at by exaggerated, unfunny caricatures. Oh, and then it becomes a fantasy episode where Roseanne thinks she’s Xena. Come on.

There are also a pair of episodes after Dan and Roseanne split up that should have been great. The first sees Roseanne driving aimlessly around Lanford, reflecting on how the town has changed over the years. The second sees her holing up in her bedroom, depressed, and refusing to come out. A better show — such as Roseanne so recently had been — would have used these opportunities to explore character, both Roseanne’s and those who tried to help her move forward in the face of domestic tragedy.

Instead, both episodes — both of them! — are little more than extended jokes on the fact that Roseanne eats junk food. Come on.

And yes, an unhealthy diet led to Dan’s heart attack at the end of season eight. And no, season nine’s junk food duology doesn’t remember or comment on that in any way.

Come. On.

Still, though! Good ideas. Credit where it’s due.

6) The kitchen table scene

The ending of the season — and, until a few months ago, Roseanne as a whole — revealed that much of what we’ve seen on the show, if not all of it, was either invented by Roseanne (the character) or heavily fictionalized.

This was a divisive revelation. The most significant difference, arguably, is that Dan did not survive his heart attack at Darlene’s wedding. (More on that in a bit.) But as much as people like to see that as a way to bracket season nine off as the contents of Roseanne’s novel and ignore it completely, the divergence between fact and fiction didn’t start there.

Roseanne also reveals that Jackie was always a lesbian, for one, and Roseanne invented a series of boyfriends for her. She also mentions that Darlene and Mark were a couple, as were Becky and David; in the episodes we saw on television, it was the other way around.

But that’s not what I really enjoyed. What I really enjoyed was the way in which these revelations were rolled out.

From seasons one through seven, the intro credits saw the family and a hanger-on or two gathered around the kitchen table. Eating pizza, exchanging Chinese food, playing poker. Everyone was together, the camera slowly panned around them as they went about their interactions, and the only sound we heard was Roseanne’s laughter to close the sequence out.

Near the end of “Into that Good Night,” season nine’s finale, we see the Conners and their friends gathered around that table again, the camera pans around, they exchange and squabble over Chinese food…but now we can hear their conversations. It’s not an intro sequence; it’s just a scene. It’s playing out for us.

And, as it does, Roseanne looks around the table. Her narration tells us how different reality was from what we’ve seen, and each character, as we watch, becomes their actual selves. Leon starts vocally praising George H.W. Bush. Becky and Darlene abandon the relationships we thought they were in and immediately take up with the other Healy brother. And Dan…well, Dan’s chair is suddenly empty.

It’s an efficient and deeply effective way of essentially undoing much of what we’d learned about the Conners. Anyone who disagrees with the direction the series finale took is, certainly, entitled to that opinion. In fact, I largely share it.

But the manner in which it was executed? It was perfect.

It was a perfectly executed gut punch.

5) Fred Willard

If I had to guess, I’d say Roseanne expected to end with season eight. So many of the episodes in that season have to do with looking backward, closing out plot threads, or both. It seems like it was written (or at least conceived of) as a natural stopping point for the characters in a way that season nine absolutely doesn’t.

Season eight saw Dan meeting up with his old band, Roseanne and Jackie rooting through boxes of their childhood toys, the kids finding loveletters Dan and Roseanne wrote when they were dating, Darlene getting pregnant, Dan and Roseanne having one “last date” before their own new baby is born…and, of course, Dan’s heart attack, which we’ll discuss later. Even season eight’s intro credits featured a series of photomorphs, showing how each character looked when the show started, evolving into what they now look like, as it ends.

One of these episodes featured Leon, a character played by the fantastic Martin Mull, getting married. In addition to this episode (“December Bride”) being sweet, smart, and a laugh riot, we were introduced to Fred Willard as Scott, Leon’s new husband.

Willard wins Roseanne over immediately, and I doubt it took the audience much longer to warm up to him as well. The guy is a comic treasure to this day, and he fit Roseanne‘s universe perfectly. This wasn’t a hollow celebrity cameo (we’d get plenty of those in season nine); this was a new character we wanted to spend some time with, laugh with, and watch Leon grow with.

Season nine might be Roseanne‘s equivalent of an unplanned pregnancy, but it at least did give us more time with Fred Willard. That in itself can never possibly be a bad thing, and it helps that Willard still manages to be funny when the material fails him. He’s a natural entertainer, a legitimately good actor, and an anchoring presence in his handful of episodes.

If anything, he served as a great reminder that for eight seasons, and right up to the end of that eighth season, Roseanne had no trouble at all producing some of the best characters on television.

4) DJ becoming a film buff

Michael Fishman was seven years old when Roseanne debuted, which meant that his character DJ spent a good number of seasons without much to do. If I really racked my brain, though, I could probably think of at least one sitcom that gave its own young actor even less business. (And, to their comparative credit, Roseanne and Dan do often remember they have a son.)

Fishman wasn’t a bad actor, but he was young enough that it was difficult to give him many stories. As such, he was nearly always on the periphery, and a few times sat episodes out entirely.

This is all fine. I’d rather not see unnecessary characters crammed unnaturally into scenes for the sake of it, and Roseanne used the kid well enough. It’s a shame, though, that he was so young for so much of the run that he didn’t get to develop much of an arc of his own.

Until, shockingly, season nine.

Allowing DJ to reveal himself as a film buff (and blossom into a film maker) was arguably the only character choice in season nine that made sense. It not only gave Fishman more to do, but it was true to DJ’s character. We watched Becky and Darlene grow up actively, because they were at more dynamic times in their lives. Certainly one changes more between high school and college, or when entering the workforce, than one changes between grades in elementary school.

DJ’s legitimate love and knowledge of cinema, though, proves that he was developing in his own way when we (and his parents) weren’t looking.

He grew up in a house with the television always on. He consumed all kinds of programs and movies that the networks showed him. The Conners getting a VCR in an earlier season was a genuine turning point for them, and it allowed them to regularly head to the video rental store for an armload of things they’ve never seen.

DJ absorbed all of it. He developed a critical eye. He started to learn about why certain films worked and why others didn’t. He developed a taste in cinema apart from the rest of his family, just as Darlene had previously developed a love of literature and writing. It became an escape, and it shaped who he is. What’s more…that’s sort of what happened to me, as well. Too much television in the house may or may not have rotted my brain, but it certainly helped inform the way I see the world, and my desire to create. I absolutely am willing to believe the same thing happened to DJ.

Also, his love of cinema introduces him to Heather Matarazzo, playing a character also named Heather. Matarazzo is another of season nine’s few consistent bright spots, and I’m glad DJ (and we!) got to spend some time with her.

3) Darlene’s delivery

Roseanne lucked out when it cast Sara Gilbert. Lecey Goranson as Becky and Michael Fishman as DJ were perfectly fine and often quite good, but Sara Gilbert as Darlene gave us one of television’s best characters overall, and one of the most important characters to me personally. Gilbert should be, for my money, the gold standard for child actors, holding her ground right alongside Roseanne, John Goodman, and Laurie Metcalf…damned good company to be in.

There’s no way anyone could have known in season one just how deeply and remarkably Gilbert would inhabit the character, how much incredible work she’d do as Darlene over the years, or the creative freedom her strong performance would allow the writers. After all, they could trust her to work wonders with whatever they gave her. Uniformly, she did exactly that.

When Becky was recast (temporarily…sort of?) in season six, it took a while for viewers to adapt. But, hey, it worked well enough. Part of the reason for this is that Goranson — and I say this with no intention of being rude — was replaceable. She wasn’t terrible, but she certainly didn’t stand in a league of her own. Somebody else could fill those shoes.

Imagine instead if Darlene had been recast. It would have been a catastrophe. It wouldn’t have been possible.

All of this is to say that even toward the dragging end of Roseanne‘s deeply disappointing ninth season, it’s no surprise that Gilbert is still doing important work.

After the character was absent from many episodes, “A Second Chance” sees Darlene going into labor prematurely. Very prematurely. And the following episode, “The Miracle,” is about her and the rest of the family coming to terms with the very real chance that the baby will not survive.

Gilbert, for obvious reasons, is not at her caustic funniest. But she does turn in an impressive dramatic performance, as does Johnny Galecki as David, who we see become an adult over the course of the delivery, leaving his detached slacker persona behind to become a supportive, attentive husband and father.

As far as emotional episodes of Roseanne go, there have certainly been better ones. But it says a lot that when they needed one at the very end of their final run, they turned to Gilbert to deliver it.

2) Dan’s death

Technically, Dan’s death came at the end of season eight…we just didn’t know it. But since the revelation happens in season nine, and since the revelation is crucial, I’m happy to give this season credit for it.

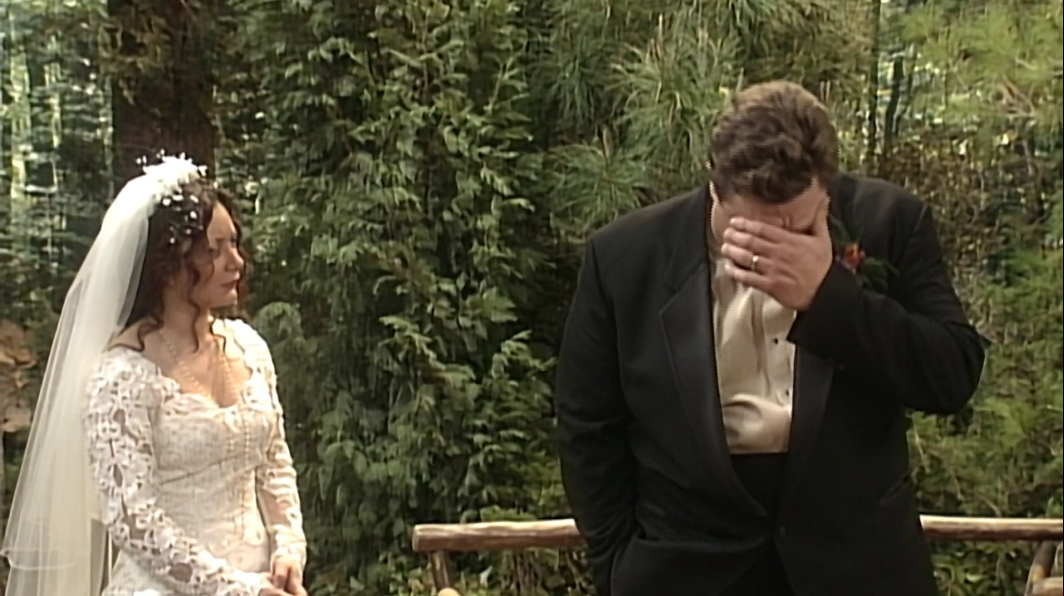

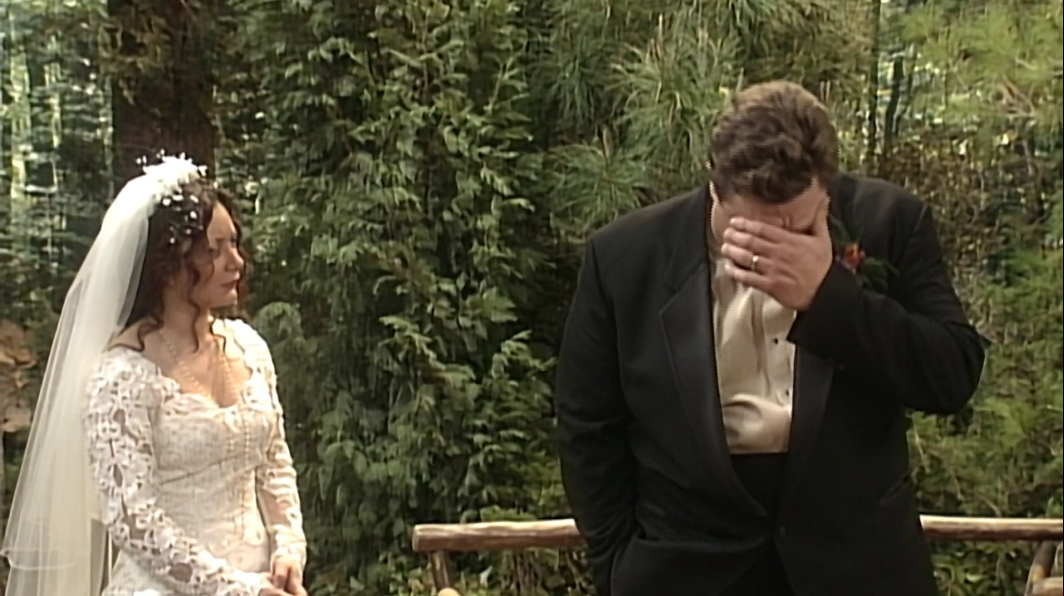

In “The Wedding,” Dan suffered a heart attack after Darlene and David got married. If I’m correct in thinking season eight was originally meant to conclude the show, I’m confident in saying this was always intended to be fatal.

And yet…he survived. “Heart & Soul” came next, and was about Dan’s recovery. Then “Fights and Stuff” saw Dan and Roseanne sparring over his reluctance to lead a healthier lifestyle. Dan was alive, and the heart attack was just something to which other characters would refer now and then.

At the end of season nine, though, Roseanne reveals that he did indeed die that day. And, frankly, that’s how it should have been.

I love John Goodman. I love Dan. But “The Wedding” builds to Dan’s death so perfectly that it’s actually frustrating he doesn’t die in that episode.

He feels off as the wedding approaches. The makeup crew does a great job of making Goodman look more sickly as the episode progresses. He loses focus as Darlene and David exchange vows. When he tells Roseanne after the ceremony that he’s not feeling well and needs a doctor, Goodman sells the idea that this is serious. That this isn’t a cliffhanger. That something very important is happening and things are not going to be the same next week.

What’s more, Dan’s death is what gives real meaning to what he says to Darlene before she gets married.

He gives her a key to a safety deposit box that nobody else knows about. It contains money and valuables. What he tells her provides important context for what should have been his death…and it’s also far better writing than any weekly 90s sitcom deserved.

That’s your just-in-case money, Darlene. Now you’ve got a baby coming, and I just think, if you had more money laying around, you’d have more chances to change…I don’t know. Whatever it is you want to change. I just don’t want you to miss any opportunities, Darlene. Everybody thinks there’s plenty of time to do whatever they want. Believe me, there’s not.

Darlene reassures her emotional father. She tells him she isn’t going anywhere; she will still be around.

We need Dan’s death as the ironic punctuation to her promise. We need it to give his speech heft. We need it because that’s why all of this matters.

Without Dan’s death, it’s just something nice a father does for his daughter.

And that’s never, ever been enough for Roseanne before.

1) The Bev / Nana Mary episode

There’s no reason a late-game episode about Roseanne’s mother Bev (Estelle Parsons) and Bev’s mother Mary (Shelley Winters) sitting on a couch and talking to each other should have been great. The ninth season was full of experimentation that went nowhere, great premises squandered, and characters that seemed to be controlled by writers who no longer cared about nor understood them.

And yet “Mothers and Other Strangers” works. I don’t mean that in a relative sense, either. I mean it’s actually a truly great episode of Roseanne, and the only one in the entire season that feels like it belongs in another.

In the previous episode, Bev accidentally outs herself as gay. It was a fine enough revelation, but it’s this episode that keeps it from being a hollow gimmick. Bev finds herself in internal turmoil as a result of her confession, and is now forced to face it herself. And, true to life, once they start addressing one emotional issue, others come to light, and they have to face those, as well.

This leads her to take a trip to see Nana Mary, one of Roseanne‘s best recurring characters. She confronts her mother about her own childhood. About the fact that she never knew her father, let alone who her father even was. She works through a lifetime of repressed frustration and anger in the course of one extended conversation with the woman she feels ruined her life. Which is nice, because we’ve seen Roseanne and Jackie accuse Bev of doing the same thing to them…and Becky and Darlene accuse Rosanne of doing it to them.

That’s the thing with families. A decision is never just a decision. The fallout spans generations. A poorly handled conflict today changes the way a mother or a father handles their own children decades from now. And so on, and so on.

Mary raised Bev in an open and free environment; Bev raised Roseanne and Jackie in a rigid and strict one. Neither, this episode suggests, was right. You’re damned if you do, and you’re damned if you don’t. Being a parent is hard. There’s never a right answer, and you just have to try really hard to not choose to worst one.

“Mothers and Other Strangers” represents a ladder of damaged women who blame each other for doing the things they’re also doing to their children. It’s a smart, emotional, funny episode that certainly doesn’t justify the ninth season, but at least gives us something to look forward to when we watch it.

It’s an episode that matters, and that’s something I can’t really say about any of the others.

There’s good stuff in season nine. There really is. The reason it’s held in low regard, though, is that we’ve never had to dig for good stuff in the earlier seasons…if anything, it was difficult to find the truly bad stuff.

On the whole, the season is pretty awful. Nothing it does right outweighs the thousands of things it consistently does wrong. But if you can’t resist watching season nine…at least you know you’ll have ten things to look forward to.

And one shockingly fantastic episode to boot.