[Note: This article originally appeared in an earlier version on Noise to Signal.]

With the looming release of Moonrise Kingdom, it’s a given that we’ll soon find ourselves awash in reviews that, predictably, betray their authors’ confusion at what it is Wes Anderson — in a word — does.

Not so much what Wes Anderson does with a particular film itself, but what Wes Anderson does as a film maker working today. Reviews often seem to want to discuss all of his films at once, and make grand dismissive statements about wooden characterization, a complete lack of emotion, and the impossibility of any human being relating to the feelings or motivations of his characters.

In response I issue this…a list of what I feel are ten thoroughly, genuinely, painfully affecting moments in his films. Anderson might not handle emotion the way most American filmmakers handle emotion (read: tears, strings and rain), but the films of Wes Anderson provide a clued-in audience with some of the most sincerely (and strangely) moving moments, which haunt and linger far longer than those of his contemporaries. So read on, share, and enjoy.

Oh, and before anyone asks…no. I did not forget about Bottle Rocket or Fantastic Mr. Fox.

10) “That’s a hell of a damn grave. I wish it were mine.”

— The Royal Tenenbaums

The Royal Tenenbaums is segmented into chapters, like a novel, or possibly a biography. But one scene stands outside of the film’s literary organization: between Chapter Three and Chapter Four, we have a lengthy installment entitled Maddox Hill Cemetery. It’s here that various characters pair off — and re-pair off — for the sake, yes, of plot development, but also for some of the film’s most truly painful Tenenbaum interaction.

From Royal shaking a few flowers free of his own bouquet for the grave of Chas’ wife to Richie giving his signature silent greeting to a passerby who recognizes him from his glory days, Neither Anderson nor his actors nor his original score composer, stumble at all. Everything is here, either spoken or unspoken. We see exactly why the Tenenbaums, on some level, yearn to operate together as a family, and also — more apparently — why they never can.

It’s appropriate that Maddox Hill Cemetery stands without a chapter number…it exists, moreso than any other sequence in the film, during several time periods, with each of the Tenenbaum children having a flashback that explains at least partly the gap between their glorious childhood and their tormented adult lives.

Composer Mark Mothersbaugh understands this scene on some level far beyond the structural and even the emotional. He understands what fuels the world in which The Royal Tenenbaums exists, and his score for this scene ranks high among his absolutely strongest work. His score here is beautiful, bashful, and aware of its own limitations. This is the music you would hear if you dropped a phonograph needle onto Richie Tenenbaum’s heart, and it stirs that rare, perfect emotion that can only be felt when a brilliant director, a brilliant cast and a brilliant composer work off of each other in profound harmony.

9) “You’re a real jerk to me, you know that?”

— Rushmore

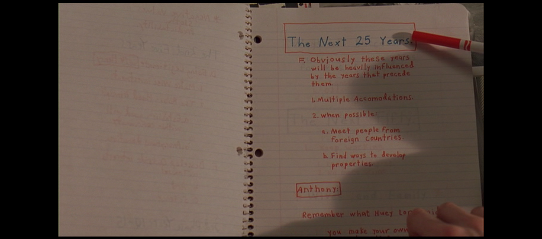

One of Max Fischer’s crimes against himself — perhaps his cardinal offense — is his habit of fixing his gaze on objects beyond his reach, and missing out on everything that’s right by his side, just waiting for him to come back around.

He seems to come to this realization himself toward the end of Rushmore, when classmate Margaret Yang stumbles upon him flying a kite. Margaret forces him to face the fact that his self-important social climb has emotional consequences as well. “You’re a real jerk to me,” she says. “You know that?” And we know that her words have taken root, because he actually apologizes — a defining moment for a very-much-changed Max.

He is sorry, because by this point in the film it’s clear his pursuit of Miss Cross has come to nothing…and a young woman who’s given him sympathy and support has been actively hurt by his callous inattention.

There’s more than a little caution — however unintentional — present in the little story she tells him as well: her science fair project was a lie. She faked the results. Max understands the gravity of what she has said here, and it stings. In fact, it’s why, immediately afterward, he decides to atone for his own falsified data by introducing Mr. Blume to his father…the barber.

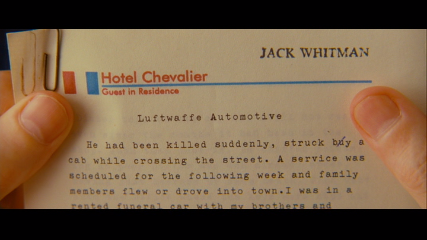

8) “The battery’s dead, too.”

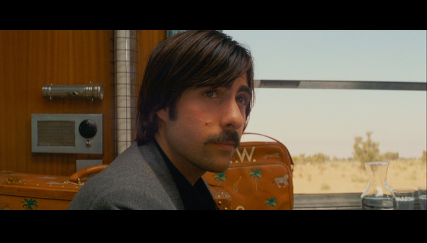

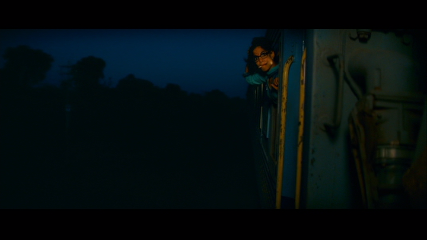

— The Darjeeling Limited

One very interesting thing about The Darjeeling Limited is that its two most affecting scenes are intertwined with one another (structurally, this one is sandwiched between two halves of the other), so that all of the film’s most brutal emotion comes in one continuous hit. Typically Anderson spreads it thin, leaving lines and gestures stranded in places sometimes very far removed from the previous or next display of emotion…not so here.

But that’s not to say he does it any less adequately in Darjeeling. In fact, this particular scene, in which the three Whitman brothers attempt without success to drive their father’s car to his funeral, is among Anderson’s finest achievements, hands down. (In fact, I’d venture to say that it would work better as a short film than Hotel Chevalier did.)

The entire scene is a display of thoroughly misplaced attention, as it’s more important to the Whitmans to drive to their father’s funeral in a symbolic vehicle than it is for them to make it on time, and they end up, it’s suggested, missing the event entirely for all their fussing. It’s symptomatic of the problems they must have faced as a family all along: it’s not that they can’t work together, it’s that when they do work together, they’re pulling in the wrong direction.

But it’s still touching, and more than a little painful, when they try their best to do what they feel must be done, and this manic several minutes, deliberately plucked from a very different place and time in their lives, is highlighted by the most impressive display of brotherhood we ever see from the Whitmans when they threaten and stare down a tow-truck driver who nearly crashes into them. Was the tow-truck driver in the wrong? Of course he wasn’t. But even when the Whitmans manage to pull together, they’re pulling in the wrong direction.

7) “I’m a little bit lonely these days.”

— Rushmore

Dr. Guggenheim’s stroke brings Max Fischer and Herman Blume together again for a brief ride in an elevator that somehow, without really saying anything, says absolutely everything anyone needs to know about these characters.

There’s not so much an obvious awkwardness between the two as there is an unspoken yearning to reconnect. They miss each other. Serious topics are touched upon (Blume’s divorce, Miss Cross’ whereabouts) but neither man is able to say anything much of substance. They bat a few banalities back, and forth and ultimately refuse eye contact.

But there is a love there…that love that rides a mutual respect, and can never quite be killed. Blume’s initial “Hey, amigo,” is a clear linguistic nod to the fact that he would still love to consider Max a friend, but cannot actually bring himself to use the word. And Max’s final line upon Blume’s departure (“Hey, is everything okay?”) is helplessly genuine. Blume’s confession of loneliness is made all the more painful by the logistical fact that, as he says it, he only allows Max a few of the back of his head. As much as they need each other, and even as they reach, they can’t yet let each other in.

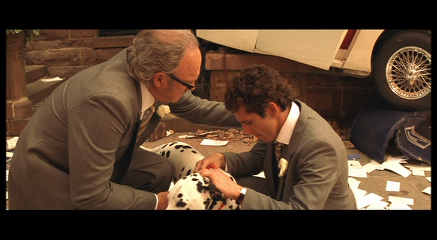

6) “I’ve had a rough year, dad.”

— The Royal Tenenbaums

When I first put together this list, five long years ago, this was one moment that I considered, and ultimately put aside. Today, I can’t account for that decision, as it’s sincerely one of the most touching things in a movie bursting with emotional merit.

As Royal Tenenbaum attempts to reconnect with his family, he meets with varying degrees of success from each of them. Without any question, however, the most difficult obstacle he has to face is Chas. Chas has been both robbed and shot by his father during the course of his childhood, but what stings most for him is the fact that his dad let the family fail. When his parents separated the children were never the same, and Chas’ channeled his frustration at his parents into shaping his own family unit, providing for them a secure and stable environment that was ultimately ripped away from him by the plane crash that took his wife.

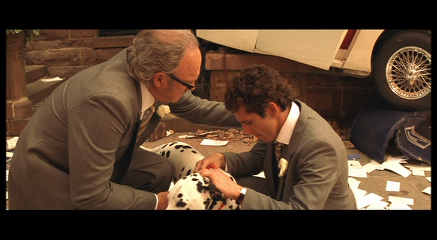

Chas did indeed have a rough year, but that’s not what makes the moment so important. It’s not the confession, but who he’s confessing it to. As much as Chas kept his emotions to himself, it’s ultimately the father who hurt hum so much that gives him the comfort he needs. The tears he cries when Royal buys his boys a new dog to replace the recently departed Buckley are real, and he sees a sincere selflessness in the gesture…one that’s superficially small, but relatively enormous.

Chas lets his father back in, but Royal is not long for this world, and he himself dies not much later. In a twist neither man could have seen coming, Chas is the one who spends Royal’s dying moments with him. It’s a profoundly emotional coda to the most openly antagonistic relationship in a film rife with them, and it’s all elevated by the genuinely moving portrayal of Chas by Ben Stiller. Proof positive that Wes Anderson can work wonders with just about anyone, and a moment as deserving of a spot on this list as any other.

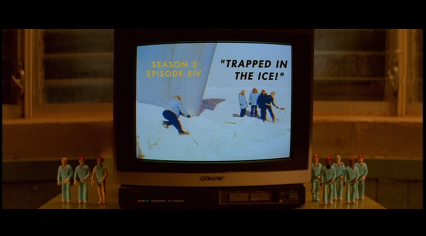

5) “All hands bury the dead.”

— The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou

We know very little of Ned’s life before he joined up with Team Zissou, and, as far as the interests of the film are concerned, that’s a good thing. It makes his last moments on board the Belafonte that much more significant.

Had we been granted a more comprehensive view of his life, Team Zissou would represent only a small portion of all those he came to know. With our much narrower perspective, the ship’s crew represents everybody we’ve seen him interact with, and their turnout to wave farewell before his final flight is almost overpowering in its significance. None of these characters suspects that they will never see him alive again, and yet they’re all there…seeing him off. It’s just one of those many morbid coincidences that none of these characters would really understand.

Most touching is Klaus’ farewell, which includes, importantly, an olive-branch by way of salute. He wants Ned to know how much it means to him that he worked a K — for Klaus — onto the redesigned Team Zissou insignia, but more importantly he wants him to know that he’s at last ready to accept him as a fellow member of the crew. (And, in terms of the de-facto Zissou family, a brother.)

Steve is the only one who does not get the chance to say goodbye to Ned, though he is present for his final moments, and it is he who pulls his body to shore. It’s more than a little telling, as well, that the sharp cuts in Steve’s “death vision” sequence are so similar in style to those of Richie Tenenbaum. The difference, of course, is that Richie lived a full emotional life with much to reflect upon…while Steve’s visions are nothing more than flat colors, bubbles rushing to the surface, and one fleeting, final glimpse of Ned, who financed the voyage monetarily, and then, with more than a little symbolism, paid for it with his life. Steve falling to his knees on shore with the body of the man who was — for all intents and purposes — his son is a beautifully framed, hauntingly understated moment of silent, unforgettable sorrow. But Ned’s not the only one to come to an early, watery end…

4) “I didn’t save mine.”

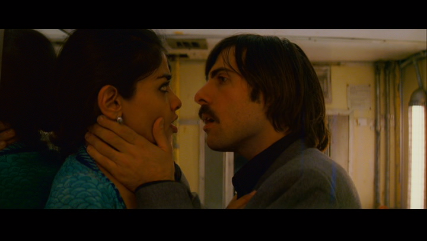

— The Darjeeling Limited

The turning-point for Peter Whitman (and arguably for the film itself) comes when the three brothers see three young Indian boys fall helplessly into a dangerous river. That’s one boy for each brother, right? And because they’re well-to-do Americans they get to play automatic heroes. There’s nothing at all at stake when the Whitmans dive in after the boys. Mathematically, everything is going to be just fine.

Imagine, then, the shock to Peter Whitman when he fails to save one of the children. He emerges from the river bloodied and bruised, carrying a lifeless body, and he’s so far beyond emotion that he can’t do anything but mutter flat, impotent confessions. “I didn’t save mine.” “He’s dead.” “The rocks killed him.” The audience might believe, initially, that Peter’s blow to the head left him stammering, but it’s clear before long that the real damage was wrought more deeply. His entire sense of life and possibility has been thrown for a loop–he was not the hero he expected himself to be. In fact, he was a failure. He ends up carrying a dead child to a grieving father, in a land he does not know or understand, and though Peter does not cry, it’s not because he feels nothing; it’s because he feels a sorrow too large to convey.

The Whitman brothers spend a good deal of time in this village, and Peter may never be able to atone for what’s happened, but he does come out of the experience with a much matured view of his own impending fatherhood, which now holds an unexpected meaning for him. He may not be a completely changed man but, after this incident, he is no longer the man he was just a few days earlier, when he openly considered leaving his wife before his child was born.

Adrien Brody, as of this film, is a newcomer to Anderson’s menagerie of reliable actors, and as of this precise moment, when he emerges from the river stuttering helplessly about the child whose life he could not save, he establishes himself as a perfect fit. (Also, for the record, Brody wins the Saddest Eyes award for The Darjeeling Limited, which is always a serious achievement in a Wes Anderson film.)

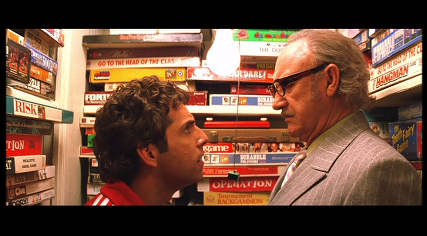

3) “Mr. Blume…this is my father, Burt Fischer.”

— Rushmore

There’s no greater change wrought in Max throughout the course of Rushmore than the one so clearly on display when he humbly introduces Mr. Blume to his father. He is letting Blume see a side of him that very few people have been invited to see, but also he is showing it to himself, letting himself, for once, be reflected in his own eyes.

One great thing about this scene that can easily go unnoticed is that the two adults are each aware of more than they’re actually saying. Mr. Blume had earlier been led to believe that Max’s father was a neurosurgeon, and it’s safe to assume that Mr. Fischer is aware that his meager occupation has probably been kept a careful secret by his enterprising son…and yet neither of them speak of it. Blume’s heart breaks, and you can see it in Bill Murray’s supremely expressive eyes, not just because he’s been allowed a glimpse behind Max’s carefully constructed shell, but also because he feels acutely the distance between father and son, preventing both parties from connecting the way they’d each like to — and need to — connect.

“I don’t know, Burt,” says Blume, apropos of nothing, and it’s one of the most honest lines in the film. Something real is being revealed to him here, and he’s incapable of coping with it. Some silent lesson is being preached, and he’s aware that its moral will be at least somewhat lost to him. He envies the simplicity of the barber’s life, and at the same time understands precisely, guiltily, the reason Max aches to rise above it.

2) “I wonder if it remembers me.”

— The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou

When Steve Zissou finally comes face to face with the Jaguar Shark, there’s very little he can do but ponder the wisdom of his journey, and reflect — wordlessly — upon everything his crew has had to endure in pursuit of his purely selfish, short-sighted revenge.

The submarine (aptly named Deep Search) contains what remains of his crew and his family…along with a business partner, a reporter, an intern, and a representative of the bond company, all of whom have suffered in some tangible way for the advancement of Steve’s goal. And yet, when he finally reaches that goal, he breaks down. He cries openly, for the first and only time in the film. He gains — a long, long way into his life and career — some perspective of the greater world around him, and he sees, at last, how little right he had to so carelessly jeopardize other people’s lives.

The real weight in the scene is the non-presence of Ned, who died in pursuit of the beast, and we suspect that the death of his previous crewmate Esteban sits heavy on Steve’s conscience as well. His emotion is coming from the fact that it took him too long to realize the price of his revenge, and that what’s lost is really lost forever. There’s no way to go back and undo the very real damage he’s done along the way.

He is forgiven, however, in the midst of his wordless reflection, by those along for the ride on Deep Search. One by one, his remaining companions each lay a comforting hand on him. There are no accusations, and there is no anger. They find themselves in a submarine with a captain who has at last become fragile and human, and, one hand at a time, they do their part to hold him together.

1) “I’m going to kill myself tomorrow.”

— The Royal Tenenbaums

There’s very little that can be said of a scene that says everything itself so well. Relied upon — and used — by so many others as the most level-headed and caring of the Tenenbaum family, the viewer is more aware than any of the characters how much suffering he internalizes. And so, when at last he learns more about his adopted sister than he was ever prepared to know, and he walks slowly and quietly out the door without saying a word, we know that something is about to happen, and it’s not going to be good.

Elliott Smith’s terrifying “Needle in the Hay” starts up, and Anderson does something very clever by starting it over an unrelated scene, in which Royal converses hopefully with a hotel manager about a job. A first-time viewer would never catch it, but upon each subsequent viewing those dark, razor-sharp chords bring a very vivid image to mind, and throughout a comic scene we are inescapably aware of a parallel tragedy.

The entire sequence with Richie in the bathroom is cut brutally, hastily…it doesn’t flow; it’s been hacked to pieces. This serves to echo not only the immediate content of the scene, but also the end to which it builds. His cutting away at hair, his beard, and then, desparately, his wrists.

It’s Anderson at his most fearless; he’s triggering emotions, but not allowing anyone to get caught up in them. There is no moment during which any characters take pause to weep. The score is not touching — it’s tough and tightly-squared. It’s played blue and emotionless, which is, of course, why it works so well. We are not asked to align ourselves with anybody else’s emotions…we are supposed to view what is happening from the perspective of an outsider. We are meant to feel growing concern as Richie removes his headband, his hair, his beard, his glasses…as he exposes himself at last to the world he sought so strongly to shut out. Layer by layer he is shaving himself down, becoming more vulnerable. And when he sees what’s beneath — that young man who, at one point, could have had absolutely anything — he attempts to destroy it.

We are allowed brief dips into his thought process by means of abrupt, almost subliminal flashes of film we’ve already seen, and it’s not so much meant to represent a dying man’s last glance backward as it is meant to highlight the agony of a man who can no longer stand to be alive.

Richie Tenenbaum still stands as Anderson’s most tragic character, and certainly the least deserving of his own pain. And that’s precisely what makes him so real.

For some reason Phil has a willful blind spot in the shape of Fantastic Mr. Fox. His spoiler review of Moonrise Kingdom (so far) reads: “It’s better than Fantastic Mr. Fox. Because come on.” Phil has set himself up for potential (and possibly well deserved) disappointment. I think Fantastic Mr. Fox has suffered unjustly at his hands. I’m hoping to redress the balance here.

For some reason Phil has a willful blind spot in the shape of Fantastic Mr. Fox. His spoiler review of Moonrise Kingdom (so far) reads: “It’s better than Fantastic Mr. Fox. Because come on.” Phil has set himself up for potential (and possibly well deserved) disappointment. I think Fantastic Mr. Fox has suffered unjustly at his hands. I’m hoping to redress the balance here. It’s not clear whether Dahl simply resented the liberties taken by filmmakers with his original material or if he actually hated the films themselves. When Danny DeVito was promoting Matilda, he was repeatedly asked in British TV interviews whether the late Dahl would have approved of his film. The answer he gave, and to be fair pretty much the only answer he could give in the circumstances was something along the lines of “I hope so”.

It’s not clear whether Dahl simply resented the liberties taken by filmmakers with his original material or if he actually hated the films themselves. When Danny DeVito was promoting Matilda, he was repeatedly asked in British TV interviews whether the late Dahl would have approved of his film. The answer he gave, and to be fair pretty much the only answer he could give in the circumstances was something along the lines of “I hope so”. Phil’s primer describes Fantastic Mr. Fox as a “curious expansion on a minor Roald Dahl story” and again I disagree. Firstly, there are no minor Roald Dahl stories. Secondly, I thought the story was very well expanded. Did I go back and re-read the original book, compare and contrast the content and then weigh up each decision that was made? No, I just thought the story on screen was better than I remembered it. I know it’s not quantifiable, but it does mean that even without the rose-tinted spectacles of nostalgia this film has achieved what must surely be best outcome for an adaptation: it’s an improvement on the original.

Phil’s primer describes Fantastic Mr. Fox as a “curious expansion on a minor Roald Dahl story” and again I disagree. Firstly, there are no minor Roald Dahl stories. Secondly, I thought the story was very well expanded. Did I go back and re-read the original book, compare and contrast the content and then weigh up each decision that was made? No, I just thought the story on screen was better than I remembered it. I know it’s not quantifiable, but it does mean that even without the rose-tinted spectacles of nostalgia this film has achieved what must surely be best outcome for an adaptation: it’s an improvement on the original. In previous films, Anderson has used his live action actors like talking props and at other times like puppets. I disagree that the subtlety this affords him in live action doesn’t transfer to his animation, but I will concede that the emphasis is different. Anderson recorded this film’s dialogue on location rather than get ‘perfect’ takes in a studio, which gives the vocals a distracted quality that echoes the feel of his live action films.

In previous films, Anderson has used his live action actors like talking props and at other times like puppets. I disagree that the subtlety this affords him in live action doesn’t transfer to his animation, but I will concede that the emphasis is different. Anderson recorded this film’s dialogue on location rather than get ‘perfect’ takes in a studio, which gives the vocals a distracted quality that echoes the feel of his live action films. The other “obtrusive hallmarks” that make a Wes Anderson film into ‘a Wes Anderson film’ are all present and correct in Fantastic Mr. Fox. The onscreen captions, the family dysfunction, the colour palette, the insert shots to exploit exposition and the moments of stillness are all there. None of which is particularly Dahl. None of which matters. I think it’s safe to say that Dahl would probably never have enjoyed a film based on his work, but I think even he would respect the care and attention that went into this.

The other “obtrusive hallmarks” that make a Wes Anderson film into ‘a Wes Anderson film’ are all present and correct in Fantastic Mr. Fox. The onscreen captions, the family dysfunction, the colour palette, the insert shots to exploit exposition and the moments of stillness are all there. None of which is particularly Dahl. None of which matters. I think it’s safe to say that Dahl would probably never have enjoyed a film based on his work, but I think even he would respect the care and attention that went into this.