The final season of The Office began last week, with the lowest-rated premiere the show’s ever had. Even lower than the premiere of the first season, which I’m pretty sure was only watched by people so that they could give it a voodoo curse. As far as season 9’s premiere? I think more people witnessed the birth of Christ. So I thought it would be fitting to look for the silver lining on the cloud of crap, and highlight each of the 10 times that the US version of the show succeeded in not being utter shit.

I know I’ll be accused of exaggerating here, but, honestly, I think I’m totally justified in saying that there were, in fact, ten distinct times that The Office rose above the level of “outright garbage” and succeeded in being “arguably watchable.” You may think I’m being too generous, but I think it’s quite fair.

So join me now as we look back at the ten times The Office managed to narrowly beat the odds, and become something that didn’t reflect poorly on viewers everywhere.

“The Fire,” Season 2, Episode 4

Why It’s Not Shit: Whenever anybody tells you Ryan is their favorite character, they’re unquestionably referring to the Ryan of the first few seasons. It didn’t take The Office long to undo what could have been their richest and most interesting character, reducing him to a generic hipster stereotype and robbing him of his complicated brilliance. This episode sees the Ryan and Michael dynamic at its best, with a truly well-handled and ever-shifting sense of power: first Michael attempts to mentor him, then ridicules him for the vast knowledge he already has, then humbly appeals for guidance himself, and finally, with irrelevant triumph, puts Ryan back in place by taunting him about a small fire he accidentally started. It’s a great, real, character-driven story that shows these two characters being the flawed — often awful — human beings they are, without resorting to caricature or cartooniness.

Why It’s Not Shit: Whenever anybody tells you Ryan is their favorite character, they’re unquestionably referring to the Ryan of the first few seasons. It didn’t take The Office long to undo what could have been their richest and most interesting character, reducing him to a generic hipster stereotype and robbing him of his complicated brilliance. This episode sees the Ryan and Michael dynamic at its best, with a truly well-handled and ever-shifting sense of power: first Michael attempts to mentor him, then ridicules him for the vast knowledge he already has, then humbly appeals for guidance himself, and finally, with irrelevant triumph, puts Ryan back in place by taunting him about a small fire he accidentally started. It’s a great, real, character-driven story that shows these two characters being the flawed — often awful — human beings they are, without resorting to caricature or cartooniness.

Why It’s Actually Still Kind of Shit: Jim leads the rest of the office in a few time-killing games during the evacuation. That’s fine, but one of them is the rather baldly intentional “Who Would You Do?” The rest of the desert-island exercises are fun, but openly asking “yo who do you want to stick your genitals in” to coworkers he barely knows comes off as perverse, and a bit revolting. Additionally, it’s odd that Kevin gets yelled at for saying “Pam” before Jim finishes telling everyone how the game is played. This makes it seem as though Kevin behaved inappropriately, which is funny, but ultimately, no, that pretty much is how the game is played…so it’s puzzling that his response was treated with disgust, as though anyone else’s later responses shouldn’t be.

Ending on a High Note: A great, early character study showing Ryan and Michael both behaving like actual people, and Dwight showing real — not overtly manufactured and instantly undone — weakness. Enjoy it while you can.

“Take Your Daughter To Work Day,” Season 2, Episode 18

Why It’s Not Shit: It’s not exactly an episode that weaves several plotlines together, but its central conceit of introducing children to the office gives nearly everyone at least one great moment, and it also provides a good example of how to sketch out the personal lives of these characters without OH I DONT KNOW SENDING THE WHOLE OFFICE TO THEIR HOUSE FOR SOME SOCIAL FUNCTION NONE OF THEM WOULD ACTUALLY GIVE A SHIT ABOUT. We also see Michael at his most vulnerable, Pam displaying a humanizing (as opposed to irritating) kind of neediness, and Stanley yelling at Ryan…which is indeed genuinely scary.

Why It’s Not Shit: It’s not exactly an episode that weaves several plotlines together, but its central conceit of introducing children to the office gives nearly everyone at least one great moment, and it also provides a good example of how to sketch out the personal lives of these characters without OH I DONT KNOW SENDING THE WHOLE OFFICE TO THEIR HOUSE FOR SOME SOCIAL FUNCTION NONE OF THEM WOULD ACTUALLY GIVE A SHIT ABOUT. We also see Michael at his most vulnerable, Pam displaying a humanizing (as opposed to irritating) kind of neediness, and Stanley yelling at Ryan…which is indeed genuinely scary.

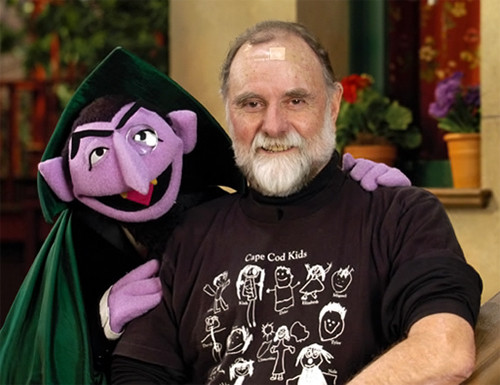

Why It’s Actually Still Kind of Shit: Everything about Michael’s appearance on the children’s show works fine, until the writers seem to think we need everyone in the room to decide for us what it means. The short moment between young Michael and the puppet should be an act of devastating restraint, but instead it’s followed up by variations on “Hey, that thing you wanted is something you never got, huh?” A little too on-the-nose, and it hurts the moment substantially. Also, it ends with Michael and Dwight singing “Teach Your Children,” which works within the episode but lays the groundwork for every future episode in which the employees sing and dance for no fucking reason whatsoever, and otherwise remind you that the show was never as good as you thought it was.

Ending on a High Note: The interactions between Michael and Toby’s daughter are a series highlight, and this is a great way to give so many characters a fun spotlight without it feeling like the isolated sketch comedy of season eight.

“Grief Counseling,” Season 3, Episode 4

Why It’s Not Shit: The death of Michael’s old boss is met by the rest of the office with a notable lack of emotion, but an opportunity to discuss, explore, and accept death comes in the form of an unfortunate bird who flies into the glass doors downstairs. “Grief Counseling” is a strange episode that manages to be sombre without losing sight of the comedy, and manages to be funny without sacrificing some genuine insight into the human condition. It’s certainly a chance to explore Michael, whose emotional responses drive the action of the entire episode, but it’s also a fine showcase for Pam, who plays into Michael’s depressive fantasies by designing a respectful casket for the bird, and delivering a monologue to her hurting boss under the guise of eulogy.

Why It’s Not Shit: The death of Michael’s old boss is met by the rest of the office with a notable lack of emotion, but an opportunity to discuss, explore, and accept death comes in the form of an unfortunate bird who flies into the glass doors downstairs. “Grief Counseling” is a strange episode that manages to be sombre without losing sight of the comedy, and manages to be funny without sacrificing some genuine insight into the human condition. It’s certainly a chance to explore Michael, whose emotional responses drive the action of the entire episode, but it’s also a fine showcase for Pam, who plays into Michael’s depressive fantasies by designing a respectful casket for the bird, and delivering a monologue to her hurting boss under the guise of eulogy.

Why It’s Actually Still Kind of Shit: MEANWHILE JIM CALLS SOME PEOPLE TO FIND POTATO CHIPS IN THE LEAST RIVETING SUBPLOT THIS SIDE OF TOBY DANCES FOR COOKIES.

Ending on a High Note: The meeting in which Pam, Ryan and Kevin relay the plots of popular movies rather than share their own stories of death is an all-time great. Also, the conclusion of this episode has a great payoff in “The Return,” when Oscar asks about Dwight and Creed replies, “You didn’t hear? Decapitated. Whole big thing. We had a funeral for a bird.”

“Traveling Salesmen,” Season 3, Episode 13

Why It’s Not Shit: Episodes that pair up characters in interesting ways and give them each a chance to shine, in the case of pretty much any show, tend to be quite good. During season 3 of The Office, the writers still remembered how to do that in a way that was organic to the situation, and realistic in terms of the work environment. While the sales calls themselves are brief we learn a lot about how these people operate day to day, while the cameras are off. We see normally suave Ryan falter, learn that the obstinate Stanley has actually built up a valuable network of business relationships, and we see newcomer Andy scheme his way to success, despite demonstrating a complete lack of aptitude. This was back when Andy alternated between conniving and frightening…two very interesting modes for the character that the show has abandoned in favor of making him sing all the God damned time.

Why It’s Not Shit: Episodes that pair up characters in interesting ways and give them each a chance to shine, in the case of pretty much any show, tend to be quite good. During season 3 of The Office, the writers still remembered how to do that in a way that was organic to the situation, and realistic in terms of the work environment. While the sales calls themselves are brief we learn a lot about how these people operate day to day, while the cameras are off. We see normally suave Ryan falter, learn that the obstinate Stanley has actually built up a valuable network of business relationships, and we see newcomer Andy scheme his way to success, despite demonstrating a complete lack of aptitude. This was back when Andy alternated between conniving and frightening…two very interesting modes for the character that the show has abandoned in favor of making him sing all the God damned time.

Why It’s Actually Still Kind of Shit: The Phyllis / Karen sales call is really just an excuse for a sight gag, and Angela’s glower during Andy’s final talking head is a bit obvious. But, to be honest, those are minor complaints, and this is a pretty great half hour of television.

Ending on a High Note: The entire thing is a high note, catching the office (and The Office) in a state of flux. New characters have been introduced, and the show is shaking up and developing existing relationships. These are both trends that would continue, but with conclusively diminishing returns. For now, the rewards are great.

“The Return,” Season 3, Episode 14

Why It’s Not Shit: “The Return” sees multiple plotlines — and ongoing dynamics — pay off in a single episode: Oscar’s “vacation,” Dwight’s resignation, Angela and Dwight’s relationship, Jim and Karen’s relationship, Jim and Pam’s flirtation, Andy’s angling for promotion, the dickishness of Jim’s pranks, and Andy’s anger issues. It’s a simple episode in which not much happens, but relationships are changed and characters are further defined. It’s a watershed episode in a show that at the time cared about what it meant when its characters said and did things, and Andy punching the wall is still as shocking a moment now as it was six years ago…only now it’s shocking because we’ve spent so much time with him as a defeated doormat that it no longer seems feasible.

Why It’s Not Shit: “The Return” sees multiple plotlines — and ongoing dynamics — pay off in a single episode: Oscar’s “vacation,” Dwight’s resignation, Angela and Dwight’s relationship, Jim and Karen’s relationship, Jim and Pam’s flirtation, Andy’s angling for promotion, the dickishness of Jim’s pranks, and Andy’s anger issues. It’s a simple episode in which not much happens, but relationships are changed and characters are further defined. It’s a watershed episode in a show that at the time cared about what it meant when its characters said and did things, and Andy punching the wall is still as shocking a moment now as it was six years ago…only now it’s shocking because we’ve spent so much time with him as a defeated doormat that it no longer seems feasible.

Why It’s Actually Still Kind of Shit: The party for Oscar and Dwight is a collection of unnecessary visual gags (Meredith in a mustache, Phyllis shaking her breasts around), but the amount of wasted time in this episode can be measured in seconds, and that’s all we can really ask.

Ending on a High Note: It’s about time there was a consequence for Jim’s immaturity, even if he’s not the one facing that consequence. Andy would return, emasculated, but we do get one truly brilliant moment with him before he’s changed forever, as he intends to apply his upwardly-mobile aggressiveness to anger management training itself, intending to complete it in half the allotted time.

“Product Recall,” Season 3, Episode 21

Why It’s Not Shit: The list of Office characters that haven’t become overplayed through the years is a short one, certainly, but Creed manages somehow to be both a continuing highlight, and consistent in his characterization. “Product Recall” is the closest thing we’ve ever had to a Creed episode, and even here he’s used sparingly. His off-camera shirking of his job responsibilities drives the plot, and he only really pops up to descend — beautifully — rung by rung into the levels of despicability. It’s a great and fittingly dark episode from an era in which the writers didn’t feel the need to soften blows and humanize monstrous behavior. We also get a great Andy and Jim pairing, and probably the only genuinely funny prank on Dwight, with Jim imitating his nemesis…and then receiving some payback in kind at the end of the episode. “Product Recall” took a lot of things that The Office so frequently got wrong, and then did them right.

Why It’s Not Shit: The list of Office characters that haven’t become overplayed through the years is a short one, certainly, but Creed manages somehow to be both a continuing highlight, and consistent in his characterization. “Product Recall” is the closest thing we’ve ever had to a Creed episode, and even here he’s used sparingly. His off-camera shirking of his job responsibilities drives the plot, and he only really pops up to descend — beautifully — rung by rung into the levels of despicability. It’s a great and fittingly dark episode from an era in which the writers didn’t feel the need to soften blows and humanize monstrous behavior. We also get a great Andy and Jim pairing, and probably the only genuinely funny prank on Dwight, with Jim imitating his nemesis…and then receiving some payback in kind at the end of the episode. “Product Recall” took a lot of things that The Office so frequently got wrong, and then did them right.

Why It’s Actually Still Kind of Shit: A Kelly subplot is never a good sign, but this one has a great moment of Oscar / Kevin bonding that more than redeems it. It’s disappointing that the cartoons look nothing like Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck, and Andy pining for a high school student is beyond creepy, but there’s enough great stuff here to warrant its inclusion, right down to the perfectly awful moment at the end, when Creed pockets the money he collected for the woman he got fired.

Ending on a High Note: Michael’s apology video may go literally nowhere, but it’s nice to see a crisis situation in this show that isn’t resolved by the staff hoisting him onto their shoulders and singing “We Shall Overcome.”

“Dinner Party,” Season 4, Episode 13

Why It’s Not Shit: It’s all kinds of not-shit up in here. If I were to single out just one episode of The Office to be spared from a nuclear blast, and I do look forward to that day that I am put in such a position, this would be the one. It’s brilliantly acted, terrifyingly raw, and unrelentingly dark. What’s more, it gives the audience credit. While some of the Jan / Michael bickering is a bit heavy handed, we’re left with a lot of blanks to fill in on our own, and even the talking-head moments don’t bother to hammer home the obvious…they’re legitimately funny, perhaps due to the genuinely unsettling atmosphere of Michael’s desperate dinner party. There’s a real feeling of entrapment and helplessness there, and none of the characters involved know quite how to act. It’s true to life and it’s human, even down to the surprisingly moving climax that silently follows each of the characters home for the night. Until this entry, we haven’t had any episodes on this list that feature the staff leaving the office for anything other than work-related (ie: understandable) reasons. Dinner with the boss, however, is a situation both rooted enough in reality to work, and rife enough with awkwardness to make horrifying. The cameras follow the staff for good reason here…not like when they decide to have a charity run for rabies, or Michael gets lost in his hometown (huh?). Like “Product Recall,” it’s an episode that takes a lot of the ingredients of the show at its worst, and reassembles them into a thing of beauty.

Why It’s Not Shit: It’s all kinds of not-shit up in here. If I were to single out just one episode of The Office to be spared from a nuclear blast, and I do look forward to that day that I am put in such a position, this would be the one. It’s brilliantly acted, terrifyingly raw, and unrelentingly dark. What’s more, it gives the audience credit. While some of the Jan / Michael bickering is a bit heavy handed, we’re left with a lot of blanks to fill in on our own, and even the talking-head moments don’t bother to hammer home the obvious…they’re legitimately funny, perhaps due to the genuinely unsettling atmosphere of Michael’s desperate dinner party. There’s a real feeling of entrapment and helplessness there, and none of the characters involved know quite how to act. It’s true to life and it’s human, even down to the surprisingly moving climax that silently follows each of the characters home for the night. Until this entry, we haven’t had any episodes on this list that feature the staff leaving the office for anything other than work-related (ie: understandable) reasons. Dinner with the boss, however, is a situation both rooted enough in reality to work, and rife enough with awkwardness to make horrifying. The cameras follow the staff for good reason here…not like when they decide to have a charity run for rabies, or Michael gets lost in his hometown (huh?). Like “Product Recall,” it’s an episode that takes a lot of the ingredients of the show at its worst, and reassembles them into a thing of beauty.

Why It’s Actually Still Kind of Shit: Michael ran through a sliding glass door because he thought he heard the ice cream man. For that tiny detail, he must have shifted from well-intentioned-but-a-bit-dumb to Benjy Compson levels of retardation. Also, Jan’s character change (competent executive to raving lunatic) lays the groundwork for all too many other characters to do the same thing…with severely diminishing returns.

Ending on a High Note: Almost nothing but great lines in this one, though the standout goes to asskissing Andy, when Michael half-heartedly asks him and Jim if they’d like to think about investing $10,000 in Jan’s home-made candle business. “Thought about it. I’m in.”

“Prince Family Paper,” Season 5, Episode 13

Why It’s Not Shit: As many of the episodes on this list are turning out to be, this one is a great character showcase: in this case, Dwight. The show doesn’t always know what to do with Dwight. He’s a psychotically-devoted businessman, an ignorant farmboy, a sensitive romantic, a violent maniac, a playful child, a sycophant and a flailing comic boob, cycling through those roles as any particular script dictates. In this case, he’s firmly in the first category, and that’s good, because that’s what should drive him as a character. In “Prince Family Paper” he pairs up with Michael for some reconnaissance work at a small rival firm. What they find there, though, is a small family running an honest business, more interested in securing their own futures than in taking down the competition. Michael, of course, goes soft when the family extends the sort of human kindness to him that he wishes he could always expect from others. Dwight, however, has a different view. “It’s not personal,” he says, and as callous as he is he has a point. “It’s business.” This is why Dwight is the most successful salesman. This is why Dwight is so devoted to his work. This is why Dwight is almost always capable of being a more interesting character than he usually gets to be. He will sink a family as long as it’s business, just as quickly as Michael would spare one in spite of it being business. It’s a great and appropriately heavy episode which more than earns its bittersweet resolution.

Why It’s Not Shit: As many of the episodes on this list are turning out to be, this one is a great character showcase: in this case, Dwight. The show doesn’t always know what to do with Dwight. He’s a psychotically-devoted businessman, an ignorant farmboy, a sensitive romantic, a violent maniac, a playful child, a sycophant and a flailing comic boob, cycling through those roles as any particular script dictates. In this case, he’s firmly in the first category, and that’s good, because that’s what should drive him as a character. In “Prince Family Paper” he pairs up with Michael for some reconnaissance work at a small rival firm. What they find there, though, is a small family running an honest business, more interested in securing their own futures than in taking down the competition. Michael, of course, goes soft when the family extends the sort of human kindness to him that he wishes he could always expect from others. Dwight, however, has a different view. “It’s not personal,” he says, and as callous as he is he has a point. “It’s business.” This is why Dwight is the most successful salesman. This is why Dwight is so devoted to his work. This is why Dwight is almost always capable of being a more interesting character than he usually gets to be. He will sink a family as long as it’s business, just as quickly as Michael would spare one in spite of it being business. It’s a great and appropriately heavy episode which more than earns its bittersweet resolution.

Why It’s Actually Still Kind of Shit: Unfortunately around a third of the episode is given over to a pointless and unfunny office debate about whether or not Hillary Swank is hot. It’s garbage. Fuckin’ trust me.

Ending on a High Note: While the episode would have been far better as a Dwight / Michael adventure with little or no input from the rest of the staff, the A plot is more than strong enough to carry the episode. Also, Michael’s “bittersweet” speech at the end of the episode is one of the only times the show truly nailed the mix of comedy and pathos that should end an episode like this.

“Dream Team,” Season 5, Episode 22

Why It’s Not Shit: The Michael Scott Paper Company arc is not only the last truly great thing the show ever did, it’s arguably the single best thing the show ever did. New boss Charles Miner lends such an air of uncomfortable change to the familiar surroundings that pretty much any arc that sprung from it would have been welcome. But Michael crashing hard against reality when he tries to start his own rival paper company is both a perfect fit for the character, and an excellent way to ground a show that was already becoming a bit cartoony. “Dream Team” may or may not be the best episode of the arc — it’s hard to say, because this particular storyline is more heavily serialized than anything else — but it’s a great distillation and exploration both of Michael’s tendency to dream too big, and why one needs to feel satisfied in his or her own life. Everything from Michael’s panicky overcooking of French toast for breakfast to Ryan stealing shoes from a bowling alley to Nana’s lucid refusal to invest in the company fills in the blanks in such a way the The Office really should have been doing since day one. And Pam’s emotional collapse toward the end of the episode leads to a genuinely moving conversation between herself and Michael. It’s a mixed moral — the fact that she quit her job is never quite presented as a good decision — but it feels like its own kind of happy ending. After all, if we have to go down, we might as well go down together.

Why It’s Not Shit: The Michael Scott Paper Company arc is not only the last truly great thing the show ever did, it’s arguably the single best thing the show ever did. New boss Charles Miner lends such an air of uncomfortable change to the familiar surroundings that pretty much any arc that sprung from it would have been welcome. But Michael crashing hard against reality when he tries to start his own rival paper company is both a perfect fit for the character, and an excellent way to ground a show that was already becoming a bit cartoony. “Dream Team” may or may not be the best episode of the arc — it’s hard to say, because this particular storyline is more heavily serialized than anything else — but it’s a great distillation and exploration both of Michael’s tendency to dream too big, and why one needs to feel satisfied in his or her own life. Everything from Michael’s panicky overcooking of French toast for breakfast to Ryan stealing shoes from a bowling alley to Nana’s lucid refusal to invest in the company fills in the blanks in such a way the The Office really should have been doing since day one. And Pam’s emotional collapse toward the end of the episode leads to a genuinely moving conversation between herself and Michael. It’s a mixed moral — the fact that she quit her job is never quite presented as a good decision — but it feels like its own kind of happy ending. After all, if we have to go down, we might as well go down together.

Why It’s Actually Still Kind of Shit: Ryan popping up for this arc makes perfect sense. Ryan sticking around after this arc makes no motherfucking sense whatsoever.

Ending on a High Note: Charles Miner installing Dwight as his number two, making Kevin the receptionist and keeping Jim at arm’s length makes for some great character comedy, as our perspective is tweaked just enough to make familiar situations feel fresh. Also, the fact that Pam ultimately returns to the company as a salesperson leaves the reception desk wide open for the last great character the show ever created: the infectiously bubbly and adorably daft Erin.

“Counseling,” Season 7, Episode 2

Why It’s Not Shit: Toby’s role in the show as Michael’s foil so rarely got a chance to shine, as Michael was always fast to dismiss him cruelly and Toby — we see clearly — was fast to believe he deserved such dismissal. In this episode, however, Michael is forced to undergo a marathon six-hour counseling session with his nemesis, and it results in probably the last truly interesting character interaction this show’s had. Michael cycles through refusal, fabrication, anger, abuse, and finally acceptance in a script that feels like it could have been written for a two-man stage show. Toby never quite gets a handle on the situation the way he wishes he did, but he means well, and even has a genuine moment of breakthrough with Michael…though, of course, once Michael’s aware that he’s opening up to Toby, he shuts it down immediately, and storms out of the session. It’s a way for both characters to have a mutually-fulfilling experience, without sacrificing the inexplicable one-sided hatred that’s fueled the dynamic between these characters all along. In the end, they bond briefly over the uselessness of Gabe in a conversation that would seem at least slightly meta, if the writers could be counted on to realize that these two are right, and there’s really no reason for that guy’s continuing presence. Oh well, at least he dressed as Lady Gaga in the Halloween episode and oh boy was that fucking funny my God this show sucks.

Why It’s Actually Still Kind of Shit: Dwight’s Pretty Woman subplot genuinely feels like a rejected idea from Everybody Loves Raymond. It’s absolutely terrible, and probably a pretty good indicator of what a Dwight Schrute-centered sitcom would look like. THANK GOD NOBODY’S DOING THAT RIGHT. The better subplot revolves around Pam bluffing her way to Office Administrator. Why they felt they needed the Dwight garbage when they already had plenty of stuff going on in this episode is beyond me.

Ending on a High Note: Dwight’s idea for a daycare center in the building is kind of worthless, but I do like the sight-gag of an Insane Clown Posse poster on the wall, with “Insane” and “Posse” crossed out. It’d be a lot funnier if the camera didn’t obnoxiously zoom in the make sure we got the joke but what can you do.

Were there any other episodes that weren’t shit? If not, let me know in the comments below. And also you’re wrong.