“River,” Herbie Hancock feat. Corinne Bailey Rae

River: The Joni Letters, 2007

On the eighth day of Christmas, David Black gave to us…

In the run up to Christmas in the year 2000, The League Of Gentlemen published A Local Book For Local People and I wanted it. I was pretty certain that I wouldn’t get it for Christmas as my mother was unlikely to buy me a book that purported to be wrapped in human skin. It’s a scrapbook collecting together newspaper articles, leaflets, postcards and letters about, to and from the people of Royston Vasey. It’s fantastic. I can’t recommend it highly enough. Comedy tie-in books are never this good. I bought it as a Christmas present to myself and pored over every page. Nestled towards the back of the book is an illustrated short story called “The Curse Of Karrit Poor,” which I skipped right over. I looked at the pictures, but I never read a word of it and I can’t explain why.

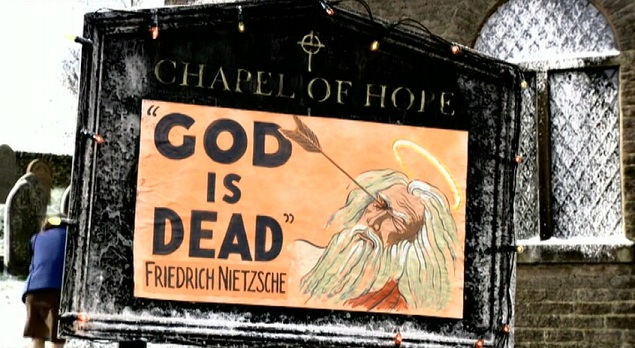

I eagerly awaited The League Of Gentlemen’s Christmas Special that year and when it finally arrived I was not disappointed. The opening sequence gives us Royston Vasey in the snow, a mutilated robin, yellow snow and a controversial Nietzsche quote on the church noticeboard. It’s a very cinematic sequence in a very cinematic episode of a very cinematic TV show and a step up from some of the other quick gags that opened earlier episodes.

It’s Christmas Eve in Royston Vasey and Bernice Woodall, the town’s vicar, is visited by three characters each seeking solace. Bernice is a fascinating choice to be our guide. The joke that the irreverent Reverend with lipstick on her teeth and a confessional full of cigarettes is presumably an Atheist and possibly the least charitable person in an uncharitable town is one that wouldn’t have sustained her for an hour. We see her character develop here as a result of each of her three Christmas encounters.

Charlie enters the church to deliver a very late and myrrhless nativity scene and takes the opportunity to tell Bernice about a recurring dream he’s been having. We cut to Charlie and Stella line dancing, putting up Christmas decorations and arguing. Charlie and Stella are among my favourite characters and I absolutely love that they get this first vignette. Reece Shearsmith and Steve Pemberton gave their relationship such depth that it always deserved to be explored further. The initial idea of the earlier sketches of the couple arguing for the benefit of a third party grows into to a brilliant short story with a fantastic twist. Liza Tarbuck, the Eyes Wide Shut coven who do voodoo and Stella’s mask are all wonderful, while the slow hand clap is unremittingly bleak.

We return to the church for one of my favourite moments in the entirety of television history: Charlie’s pause and subsequent answer to Bernice asking “In your heart of hearts, do you love your wife?”

Charlie departs and is soon replaced by another storyteller. Andrew Melville is fantastic as the old Matthew Parker, but I must confess that for years I was convinced it was Mark Gatiss in heavy make-up. He takes us back to 1975 in Duisberg in Germany and into the home of Herr Lipp. This is another short tale with another brilliant twist that I certainly didn’t see coming and a raft of sexual innuendo and references to Vampire films. Gatiss and Shearsmith are wonderful as Frau Lipp and young Matthew Parker respectively, but the truly astonishing thing about this segment is that Pemberton manages to take a grotesque character, not to mention a sexual predator, like Herr Lipp and yet give him a genuine sense of pathos all the while being very funny into the bargain.

Herr Lipp: Sometimes the inside of something can be beautiful, even if the package isn’t…well…isn’t.

And later:

Matthew: Leave me alone.

Herr Lipp: I will try.

Out goes Parker and in comes a bloodied Chinnery for our third story as the vet tells the vicar about his great-grandfather.

Bernice: Oh God, it’s getting like bloody Jackanory in here.

The resulting tale is as rich and classy a slice of Victoriana as the BBC has ever produced. Frances Cox, Freddie Jones, Boothby’s bicycle, “next door,” and seeing Chinnery as his own great-grandfather are all great.

Boothby: Now then, lad. Old Majolica sings your praises and that’s good enough for me. I can offer you a hundred a year, food, lodgings and unlimited use of a bicycle. What do you say?

Chinnery: I’d be delighted.

Boothby: Capital! I think we’ll get along well. There is only one other matter, my senior partner, Mr. Purblind, is an invalid. He occupies the last room on the third floor. He never stirs from his bed from dawn till dusk…save to go for a wee.

Chinnery: You wish me to visit him?

Boothby: On no account! Mr. Purblind is a very sick man. The slightest disturbance is abhorrent to him. Do you hear me?

Chinnery: Yes, sir.

Boothby: All my doors are open to you, Chinnery. Except the ones that are closed.

For their part, Shearsmith and Pemberton’s creations Boothby and Majolica are wonderful, with the former’s bicycle obsession and the latter’s evil echo of Series Three’s Dr. Carlton being particular highlights.

Purblind: Touch them and see!

Chinnery: No…no, I…I mustn’t!

Purblind: Feel them! Feel the knackers!

In spite of his warning (and probably because of it), Chinnery later finds himself in Purblind’s room where the old man tells him the story of how he came to be cursed to kill every animal he came into contact with. The effect of Purblind’s story builds through the brilliant use of shadow puppets to the surprising reveal of a unique necklace and via a gleeful moment of Freddie Jones swearing. Chinnery feels the knackers and unwittingly takes Purblind’s curse upon himself, but dismisses the possibility as “cheap mummery.” His return to his London practise and a simple surgical tap that is but “the work of moments” causes an animal massacre of epic proportions.

Majolica: Another vet has touched the monkey’s bollocks. And now you and all your descendants shall suffer the curse of Karrit Poor!

There’s that name again. Every time I watch this I mean to search out my copy of A Local Book For Local People to read about the curse of Karrit Poor in “The Curse Of Karrit Poor.” I never do. We return to the present day and Bernice convinces Chinnery to get back to work.

Throughout its first two series, the show referenced and alluded to a great many horror films, but uses its Christmas Special to pay tribute to an often overlooked subgenre: the portmanteau film. These are films made up of shorter stories united by framing device. It was a subgenre that I was previously unaware of, but examples include Dr. Terror’s House Of Horrors (1964), The House That Dripped Blood (1970), Tales From The Crypt (1972), New York Stories (1989) and Four Rooms (1995).

The absence of Tubbs and Edward really allows some of the other characters to flourish and the portmanteau sequences allow the Gentlemen to have their cake and eat it too. Did those events happen as described? Will Stella be framed for murder? Is Herr Lipp a Vampire now? Is Chinnery’s inability to keep a patient alive the result of the curse? Possibly, but would it really matter if the only thing that really happened were the sequences set in the church? I don’t think so, because they are arguably the most horrific of all.

The framing story of Bernice has given us flashbacks to her childhood and reveals that her mother was abducted at Christmas when she was eight years old. She is invited by three visitors to reassess her attitude to Christmas and she does mellow as the evening has wears on. To the point that she inspires Chinnery, plans to do nice things for her parishioners on Christmas Day and, potentially a first, she apologises to someone. Bernice’s childhood catches up with her as Santa Claus comes to town again and this time he takes her away with him. Papa Lazarou’s fleeting appearance here serves to cement him as one of the most horrifying television monsters. Not only does he steal Christmas, but he undermines everything that has happened to Bernice all night. Even after the life changing visits of Scrooge’s three ghosts, it would probably have brought his new demeanour to a brief conclusion if he had been kidnapped and inserted into an elephant on Christmas Day.

There was a definite shift in style as the series progressed. While the first series could be legitimately described as a sketch show, the second was more of a sitcom. Now with the benefit of hindsight it’s easy to see the Christmas special as the bridge between that and the more comedy drama style of Series Three. Not least because they dropped the laughter track and the funny thing is that you barely notice here

The three onscreen members of The League Of Gentlemen are rightly applauded for their acting abilities, indeed we can all be grateful that three of Britain’s best actors were on screen at the same time, but in complimenting that aspect of the show let’s not ignore the writing and the fourth Gent, Jeremy Dyson.

The genius of The League Of Gentlemen is their juxtaposition of highbrow and lowbrow. They can take a brilliantly intricate and rewarding story about voodoo revenge and dismiss it as a cheese dream. They can take a potentially one note character with pun for a name and single entendre dialogue and play him with complexity and honesty. They can make a sumptuous Victorian horror story full of intrigue and have the entire thing revolve around the cupping of a monkey’s lovespuds. They can take something as potentially sentimental and syrupy as a Christmas special, force its bitter central character through the wringer, make her learn a lesson and then ultimately prove her right all along. They take a central tenet of sitcom, that characters don’t develop, and then they earn it.

Here I am twelve years later and I’ve finally gotten around to reading “The Curse Of Karrit Poor” in A Local Book. I liked it. Not more than the TV version, but I liked it. The one thing I found most comforting and reassuring was that it also takes both the high road and the low road.

“A story so fantastic that it might seem to have sprung from the ravings of some brain fevered Eastern mystic. Or a twat.”

–From The Curse Of Karrit Poor, being the reminiscences of “Dr Edmund Chinnery R.C.V.S.”

Tomorrow: A very adult show for children reminds us of just how far apart these phases of our lives can be. (Not intentionally, obviously.)

On the seventh day of Christmas, Jeff Zoerner gave to us…

Set the dial on your hot tub time machine for Christmas Eve, 1971. Behold, it’s the Partridge Family, and they’re stranded in a ghost town! While they wait hopefully for an über-butch Keith to effect repairs on the family bus, a lonely old prospector entertains the family in his shack with a fanciful tale of the town’s past glory days. Will Keith fix the bus in time for the clan to make it home for Christmas? Will the senile old hermit’s narrative not suck a fat, greasy one? Can I at long last make it through leering at Laurie for an entire episode without spanking one off?

When I was offered this plum assignment, this was the first and only Christmas episode to come to mind. (Why I didn’t instead think of Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer, the definitive Christmas classic, is beyond me.) Its official title is “Don’t Bring Your Guns to Town, Santa”–no relevance to the story, of course, but rather a shameful attempt to gain cheap heat from the Johnny Cash song with a similar title—and it holds a special place in my heart. But I haven’t seen it in 40 years. Will my childish assessment of the episode’s greatness hold up to adult scrutiny?

After all, it’s amazing how well many of the things we loved as children stand up in our adult years. In my case I can cite Peter, Paul, and Mary, the Kingston Trio, The Odd Couple, Johnny Cash, Monty Python…the list goes on. For this reason I am eager to relive this very special Christmas memory and see whether it is worthy of its place in my heart.

And, fortunately, thanks to the miracle of YouTube, I can do just that. So back to the episode: As you recall, the grimy old prospector is regaling the Partridge family with his crappy yarn from days gone by. For the viewers at home, the story is dramatized with the Partridge family members playing the various roles, with Charlie the prospector providing the voice-over when needed.

There are several good omens. That Keith, he sure has a nice singing voice. And Laurie is every bit the sizzling fuck-bomb I remember… my resolution to keep it in my pants doesn’t even last 30 seconds.

Then, alas, there’s the episode itself.

Mother of mercy, God must be against me. My heart sinks as I watch. The characters are painfully inauthentic. They’re not hip, as I remembered…they’re just nerds! And God damn, that kid Danny is ugly! They sure make him out to be an asshole, too. The poor guy is the kind of kid that adults find charming and other kids just want to pound into shitmeal. No wonder he went crackers as an adult…who wants to look back on his childhood and see himself being exploited as a buffoon for a nationwide audience?

As for the story…I won’t even recount it, because it’s not even trying to make sense. Example: in one scene, the sheriff, a lollipop-licking Keith Partridge, bumps into the town’s street sweeper and proceeds to–yup, you guessed it–stick the lollipop under his hat. WHAT THE FUCK??

The cherry on top of this squishy mound of shit is prospector Charlie’s inept narration. Is he drunk? Stricken with Alzheimer’s? A little (or lot) of both? The guy playing the role, Dean Jagger, has an Oscar under his belt… so how is it that he manages the worst thing about this whole debacle by far? You’re like, send this old motherfucker off to the taxidermist already. Confiscate his SAG card and delete all mention of him from Hollywood records. Find out where his kids live and pay someone to take their knees out with a baseball bat. Christ, he’s just awful. Seriously, they could have squeezed a better performance out of some random homeless guy for a free lunch.

So when it comes to pass that the Partridges’ bus is fixed and the family departs, abandoning this grubby little man to wallow in lonely squalor, you can’t help but cheer. That’s what the asshole gets for being such a bad actor.

But still, this is Christmas. And while you may realize on an intellectual level that it’s all bullshit, and that these hack TV writers are trying to pull at your heartstrings in the worst way, a part of you still wants this filthy old fart to have his Christmas miracle. You hope in spite of yourself. You hope even as you hate yourself for it.

And, as you struggle with this, something extraordinary happens…

What’s that racket wafting through Charlie’s window? Could it be? A rendition of the stomach-churning “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas” so watered down it makes the Carpenters on valium sound like Judas Priest? And who’s that gathered in front of Charlie’s shack? Is it the lunchtime buffet entertainment crew from the Cracker Barrel? Why no, it’s the Partridge family, come back to keep Charlie from experiencing Christmas alone!

And does Charlie do? I tell you what Charlie does: he TOTALLY REDEEMS this episode.

This is no exaggeration. In a few heartwarming seconds, Charlie makes the entire episode worthwhile. And how, you ask, does he do this?

By standing there.

I shit you not. By standing there…and doing it surpassingly well. He stands there, beside himself, speechless, in overjoyed disbelief that anyone would sacrifice of themselves to make his life a little brighter. He has never experienced anything like it. And neither have I: a simultaneous desire to cry and to blow my brains out. I am whisked back 40 years, and I realize I fought back tears as I watched this for the first time, just as I am now. This fucking old guy…how does he do it?

With this one scene, Charlie reminds us all of the real meaning of Christmas. Life may be shit, and the world may be shit, but from the shit can rise moments of beauty, beauty that shouldn’t be but is. And if you are honest about the nature of the world around you but are too cowardly to kill yourself, really, can you ask for anything more than this?

It is beautiful. Yes, I’ve been ruthless so far, but it’s all in good fun. I love this episode, and I am grateful for it.

Having arrived at this epiphany, I am free to move on. I freeze-frame a close-up of Laurie and spank one off… just because I can.

Merry Christmas, everyone!

Tomorrow: A gothic, grotesque Christmas of horrors. But enough about my childhood! ZING. I ZINGED MYSELF.

On the sixth day of Christmas, Jacob Crites gave to us…

The Ending of LOST is still one of the more controversial television events of the past decade. Maybe you thought it was beautiful (like me), maybe you thought it was painfully heavy-handed (like most people), and maybe you thought they were dead the whole time (which they weren’t, you dope. Go watch it again). But if there’s one thing every LOST fan can agree on, it’s that “The Constant” marked a creative and emotionally resonant peak for the show, and is perhaps one of the finest hours of television ever produced. It also happens to be a sort-of-kind-of Christmas episode. But perhaps it’s fitting that LOST‘s only Christmas episode isn’t really a Christmas episode, because “The Constant” is a LOST episode that isn’t really a LOST episode, or perhaps it is the perfect example of what a LOST episode should be.

I really don’t know. LOST was always confusing like that.

Now, LOST was such a spectacular show in part because of how unpredictable it was, and not just from a plot-twist standpoint, but from a structural standpoint. Throughout its six season run, there were many wonderful episodes, several weak episodes, but never a formulaic one, in part because there was never a formula established in the first place. Just as we were settling into a groove with flash-backs, the series would throw in a clip episode, except with clips from another part of the island featuring new characters which we had not previously seen (“The Other 48 Days”), or an episode that takes place entirely in the past (“Flashes Before Your Eyes”), or introduce the concept of a flash-forward (“Through the Looking Glass” and all of season four), or a flash-sideways (most of season six…sort of). But what could always be predicted about an episode of LOST is that it could not be predicted, that the episode would not in the least be self-contained, and that characters would generally end up in a much worse place than when they started. And this is where “The Constant” becomes rather special.

The Constant is one of perhaps only two episodes of LOST that succeed as self-contained works (the other being the pilot, which remains one of the best pilots in the history of such things). One does not need to see the previous half-billion episodes and be up to date on their backgammon visual allusions and Dharma mythlogy to understand what is going on (though it helps); this is an episode with its own unique narrative structure, a single character arc, and one of the show’s most satisfying emotional resolutions. Also, it’s Christmas, and the episode’s lead character is often portrayed in the show as a Christ-like metaphor. So there’s that.

That Christ-like metaphor in question is Desmond Hume (to reveal why he’s Christ-like metaphor would spoil much of LOST, and also, who cares?) and Desmond Hume has become unstuck in time. Only not his body, so much, but his consciousness. Desmond has recently been exposed to an inordinate amount of electromagnetic energy, and in LOST, that generally means (as Daniel Faraday will tell us) “side effects.” The side effects in this case being consciousness-time-travel, which would not be all that bad were it his present consciousness doing the traveling, and not his 1996 consciousness. But it is the latter, and in 1996, Desmond is in the Queen’s Army. This is inconvenient.

And thus begins a great deal of madness. The episode follows Desmond’s consciousness as it jumps back and forth through time with increasing frequency. It is the sort of thing that would drive anyone crazy, and that, as we find, is the trouble. What Desmond needs to keep from losing his mind completely is a Constant—something that exists in both his present (1996) and the show’s present (2004) to help his mind from collapsing with disorienting confusion. The Constant, it would turn out, is his one true love. Penny.

To save himself (and, in effect, their relationship *BOOM*) he must find Penny in 1996 and get her to call him (he’s on a freighter off the Island with access to the phone…it’s a long story) eight years in the future to the day and hour. Which is 2004. Christmas Eve.

Now, I, like many other of the show’s characters, do not celebrate Christmas; but I also, like most people with a beating heart, do always enjoy a good “Christmas Episode.” The Christmas Spirit, in actuality, is more of a nice thought than a really nice thing; during Christmastime, people are generally quite stressed about the difficulty finding parking spaces, the annoyance of hanging elaborate decorations that are only really fashionable for about three weeks, and being forced to buy presents for people they may not very much like.

But in Christmas Episodes, The Christmas Spirit is a wonderful thing, wherein faith is rewarded, relationships are rekindled and true love is often found. This is why “The Constant” is sort-of-kind-of a Christmas Episode.

LOST was always a show that attracted people of all kinds of faiths and all levels of cynicism (which is why a good deal of people were put off by the fact that one of its final scenes took place in a Church), and this is why it does not beat its Christmas setting into the ground; but even non-Christmas-Celebrators usually are fond of the things that Christmas is supposed to bring (indeed very few people despise gifts and bright colors and good will among men), and this is why everyone, regardless of personal beliefs, loves “The Constant.”

I will not ruin the ending of the episode, because I think you should watch it, but suffice it to say it is a happy one. It is about losing your mind only to find it in a better place, about resparking relationships that were once doomed to fail, about finding true love when it is at its most needed, and being rewarded in the faith that sometimes people will do the right thing. Basically, it is an episode in which good things happen to good people, a thing for which LOST was not, until its final season, very well known. That it is a Christmas Episode is not important, or perhaps it is incredibly important. I really don’t know. LOST was always confusing like that.

Tomorrow: Come on, get merry!

On the fifth day of Christmas Ryan gives to us…

Frank Costanza is without a doubt my favorite character on Seinfeld. For somebody so short-tempered, constantly screaming at those around him over the smallest nuisances, there’s remarkably not a single trace of unlikability to be found in the man. It’s a shame that his death was implied during the reunion story arc of Curb Your Enthusiasm, but with the failure of his “serenity now” relaxation cassette, I suppose it was inevitable. Fortunately, Frank plays a starring role in what’s considered to be one of the most iconic episodes of Seinfeld produced, season 9’s “The Strike.”

You know, the episode where Kramer returns to work at a bagel shop after being on strike for 12 years.

Okay, so most people know it as the Festivus episode, where we discover that Frank once invented his own holiday in response to the commercialization and religious aspects of Christmas. Subsequently, this gives us further insight into why George is the man he is today, as it turns out that Festivus was always a pretty traumatic experience for the boy.

The traditions of the holiday included an aluminum pole instead of a tree (no decoration required — Frank finds tinsel distracting), and grievances were exchanged rather than presents – a chance for the Costanzas to speak about how much they had disappointed each other over the past year. Back in the present day, Kramer finds out about Frank’s holiday and convinces him to restart the celebrations after years of lying dormant, much to the misery of George and the imperative sense of schadenfreude from his friends. The pole comes out of the crawl space and Frank couldn’t be more joyous.

The ending of the episode is a great example of why I love Seinfeld so much – its “no hugging, no learning” policy stays true during what would be a sentimental closing for so many other Christmas specials. Family and friends are gathered together on a winter backdrop, but there’s nothing of comfort to be held. George has fought the idea of Festivus all throughout the episode, yet we end with him more emotionally distraught than ever, being forced into yet another Festivus tradition, the “Feats of Strength.”

Frank: Stop crying and fight your father!

This is what a Christmas special should be. While I find that some of the more warmer, “emotional” holiday episodes of other shows do bring me some entertainment – I’m clearly aware that it’s fake. When my family reunite during the holiday season, the warmth and closeness pales in comparison to what’s presented on TV. That isn’t Christmas, and without sounding too cold, it hopefully never will be. Yeah, maybe in some families things aren’t treated so callously. I don’t know, and I don’t want to know. But I’m positive that I prefer my entertainment to treat Christmas with some realism, in the sense that I’d take Frank Costanza physically fighting his crying son over let’s say, a warm embrace after verbally accepting their differences. God, I actually felt sick writing that.

The Brady Bunch, the Huxtables, the family from Full House whoever the hell they were, even the goddamn Simpsons – when compared to the Costanza family, I know who I relate to more.

As mentioned earlier, this episode also involves Kramer working at H&H Bagels. His working life is cut short however, after being denied the 23rd off to celebrate Festivus, resulting in yet another strike. I always found the moment where he announces his protest hilarious, like he’s looking for any reason to stop working again. This is confirmed by the end of the episode, where he responds to his firing with a satisfied and hefty, “Thank. You!” It probably beats “The Bizarro Jerry” as my favorite “Kramer actually gets a job” story. I think. Maybe. The latter does have Sheena Easton.

The beginning of the episode features Dr Tim Whatley’s Hanukkah party, who’s still Jewish after seemingly converting for the jokes in the previous season. There Jerry meets his girlfriend-of-the-week, a two face (like the Batman villain, if it helps) in which she somehow changes from attractive to ugly without warning. Innocently, every time I watched this episode as a child, I could never see how she was supposed to be portrayed as ugly. After a lifetime of media influence, it’s totally clear to me today, but I think it’s a cute memory looking back. Or maybe it’s depressing, what with our idea of beauty being influenced by society and everything. Still, it doesn’t subtract from the fact that it’s a bloody hilarious story, and introduces the fact that Monk’s (the coffee shop they always visit) is actually a pretty awful restaurant.

Gwen: Jerry, how many times do we have to come to this place?

Jerry: Why? It’s our place.

Gwen: I just found a rubber band in my soup.

Jerry: Oh, I know who’s cooking today!

Meanwhile, George, in an attempt to weasel out of the spirit of giving, hands out phony donation cards to everyone at work (“A donation has been made in your name to the Human Fund. The Human Fund: Money for People”). His boss, Mr Kruger, catches onto this scam, until George admits that the only reason he succumbed to such a misdeed was because he doesn’t actually celebrate Christmas, the concept of Festivus finally proving useful for another one of his lies. Committed to his story, George brings him along to his father’s Festivus celebration.

Frank: The tradition of Festivus begins with the “Airing of Grievances.” I got a lot of problems with you people! And now…you’re gonna hear about it. You, Kruger. My son tells me your company stinks!

George: Oh God.

Frank: Quiet, you’ll get yours in a minute. Kruger, you couldn’t smooth a silk sheet if you had a hot date with a babe… I lost my train of thought.

“The Strike” opens with a Hanukkah celebration and closes with Festivus. Even though Seinfeld Christmas episodes never really dwelled upon the traditional aspects or clichés of the holiday too much, I like how this one goes to the extreme and yet puts me in the holiday mood more than any of them. Like so many others, I originally found the idea of Festivus to be comical and undeserving of celebration. Today I adore the holiday and everything it stands for. And while I’ve never convinced anybody to participate in a “Feats of Strength” (yet), I’ve gone so far as to hand out “Human Fund” donation cards in lieu of of actual gifts, whether the recipients were Seinfeld fans or not. I’m not being cheap or anything. I’m just afraid that I’ll be persecuted for my beliefs.

I’m overjoyed that Festivus has reached a certain popularity in today’s society. The real holiday began in 1966 by Dan O’Keefe’s father, but of course was made popular when he brought it to Seinfeld. Fictional additions such as the pole were then incorporated to the point where there’s fucking Festivus pole lots. God, I love it. Christmases can go by where I don’t even think about certain Christmas shows or specials, but The Strike is undeniably the clear exception. Last year, somebody actually greeted me with “Happy Festivus!” and hadn’t even seen an episode of Seinfeld or knew that it was referring to the show. I don’t find that charming, by the way. What a despicable person. Still, the cultural significance given by “The Strike” has perfected the episode itself, not that it didn’t need much to push it there. A great episode, and in my opinion, the best of season 9.

Oh, and there’s also a plot where Elaine wants a free sandwich.

Tomorrow: It’s not all comedy around here, you know; we like serialized drama too! Well, some of us do. Or one of us does. Maybe…