I’ve always been in love with Mega Man, and in the time following Mega Man 10, my love was at its highest. That game was good. Its predecessor was great. I replayed the series. I learned how to finish each level without taking damage (up to Mega Man 8, at least; I didn’t have an easy way to emulate the games from that point forward, and restarting them on actual hardware each time I took damage was far too time consuming). I started exploring the spinoffs and subseries that I’d never gotten around to.

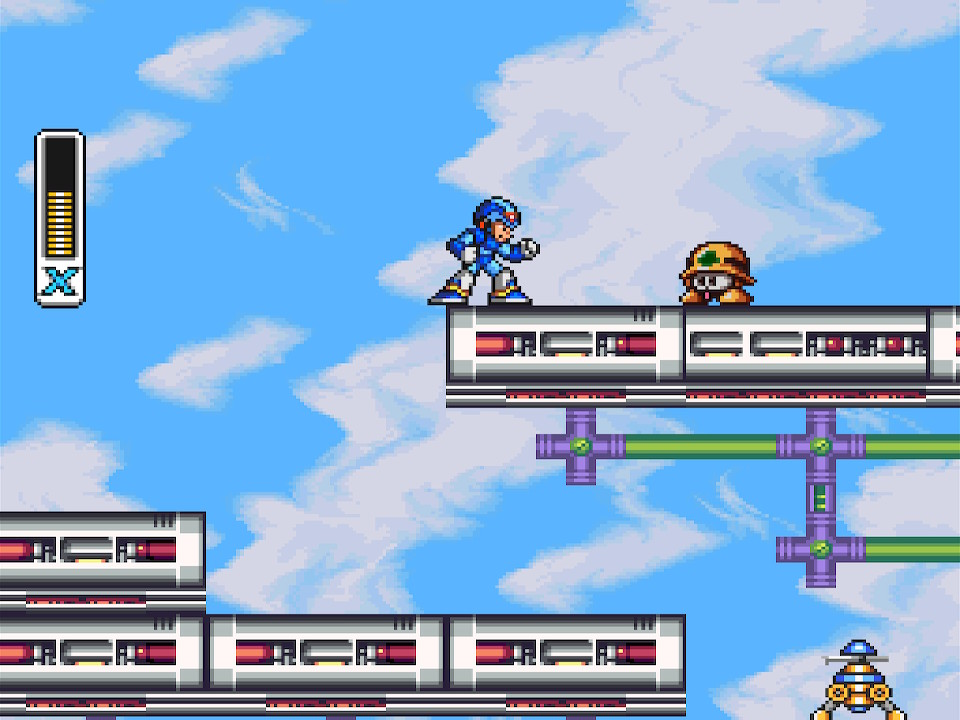

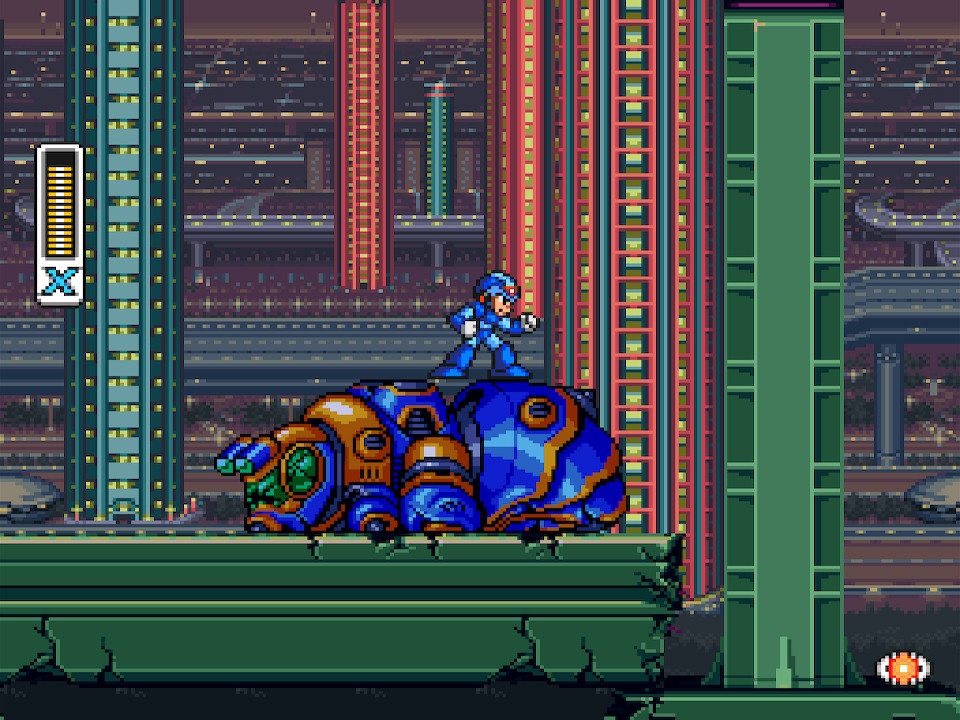

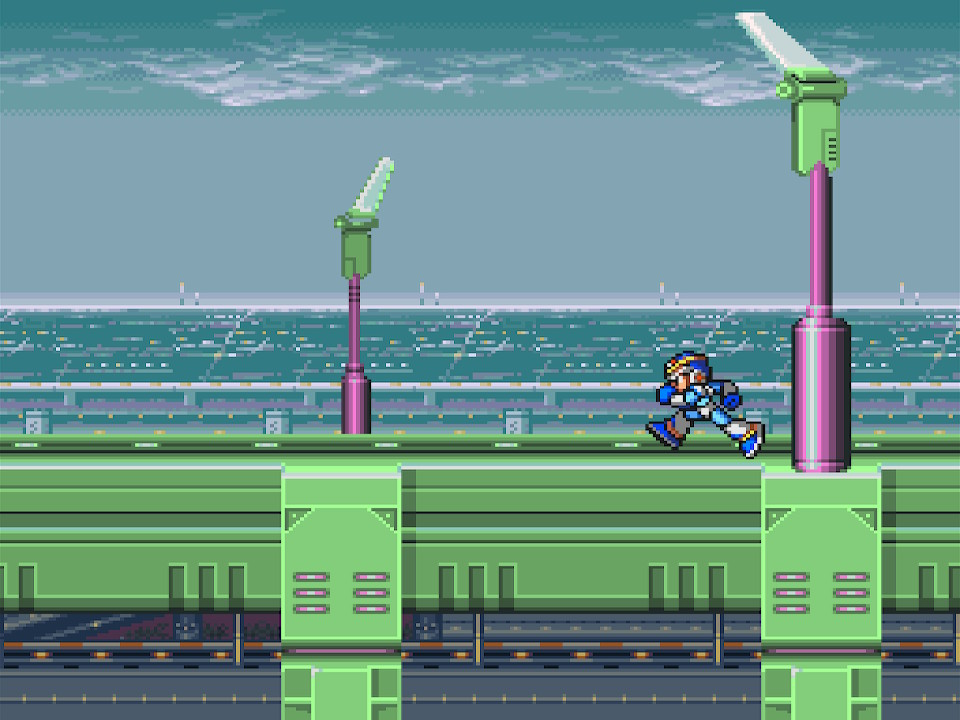

I’ll mention now that this was when I had my first proper exposure to Mega Man X. I’d rented that game at some point near release, and while I didn’t hate it I also didn’t stick with it. I’m not sure if I even bothered with Mega Man X2 or Mega Man X3, and I certainly didn’t play the others. After Mega Man 10, however, finally, with my love of the Blue Bomber as great as it had ever been, I gave that entire series a shot.

If you’re interested, maybe I’ll do a similar set of writeups about those games. For now, I’ll just say that I enjoyed them a great deal. Not as much as the main series, but Mega Man X and many of its sequels represented an admirable and fascinating evolution of the formula.

Then I played through the Mega Man Zero games, which I fucking loved and which are now my favorite series under the Mega Man banner as a whole. I played many of the RPGs, which were fine. I played through Mega Man ZX and its sequel, which were flawed but quite good. I played Mega Man Legends and its sequels, for a bit at least, but never quite found myself enjoying them.

That’s okay. All of that is okay. I’m sure there are those who dislike Mega Man Zero but love Mega Man Legends. I’m sure there are those who only enjoy the RPGs. I’m sure there are those who swear by the Mega Man X games but feel that the main series is archaic and needlessly difficult.

All of these are valid opinions. My only point is that I was willing and able after Mega Man 10 to track down everything I had missed, replay everything I already loved, and immerse myself in the franchise in a way I never had before. It was at this point that Mega Man — however you’d like to define Mega Man — cemented itself as my favorite series. I didn’t love all of it, and some of it I didn’t even enjoy, but I experienced as much of it as I could. I loved it even through its flaws, its idiocy, its worst impulses.

For most series, I simply love the games that I love, and I ignore or spend much less time with the games that I don’t love. That’s…well, that’s just healthy. For Mega Man, though, I’d find myself replaying even the games that I disliked. Sometimes my opinion would improve (a bit), but most of the time I’d only find my dissatisfaction reinforced. And then I’d come back again and again and again anyway.

I loved these games, even the ones that I hated.

And so when Mega Man 11 came out in 2018, I was excited. I’d had years of dedicated Mega Man experience behind me, and I would finally get a new installment to dig into and fall in love with. And, hey, even if I didn’t like it, I’d be guaranteed another set of Robot Masters to perfect, another set of theme tunes to add to my iPod, another game to simply play through from front to back whenever I felt blue.

I got none of those things. I bought it. I played it. I promptly forgot about it. I played it again at some point and forgot about it even more quickly. I’ve tried several times to work up enough enthusiasm to write about it for this series, and I couldn’t do it. Even now, four years later, I’m struggling.

It’s not that Mega Man 11 is terrible. Mega Man X7 is terrible, and I’m positively dying to replay that just so I can tell you, at great length, how terrible it is.

The problem is that Mega Man 11 is worse than terrible; it’s uninteresting.

There are aspects of Mega Man 11 that I feel are very good. There are aspects of Mega Man 11 that I feel are very bad. However, the overall product — the ultimate experience of playing it — just leaves me feeling…nothing. The game has high points and low points, but even its highs and lows feel so generic that my brain can’t retain them. They just slide into and out of my consciousness without making an impact, man.

All of which makes it difficult for me to want to discuss Mega Man 11 for this series. I’d like to cover it — that’s the whole point of Fight, Megaman! — but I don’t feel right telling everyone to gather ’round for another discussion just so I can launch into several hundred variations of, “It’s kinda bland and it kinda sucks.”

Maybe it’s worth taking a different angle, then; why doesn’t Mega Man 11 leave an impression? Why are so few fans of the series talking about it? Why did it disappear so quickly from everybody’s minds?

We will explore those things. And we will explore them by asking two more questions. What is Mega Man 11? And what is Mega Man?

Let me first take a look at a pair of other releases from 2018, each of which similarly attempted to tap into nostalgia for very specific older games.

I recall a review of Timespinner (which I think is similarly bland, though I’m certainly in the minority on that). The reviewer said that the game was so inspired by Castlevania: Symphony of the Night that it even borrowed what the reviewer thought was a strange quirk: In both games, attacking stops you in place, but if you hop before attacking, you’ll be able to keep moving.

The reviewer was baffled that anybody would think to adopt that design choice in their homage. I disagree completely; nobody is obligated to implement that feature into their Symphony of the Night-inspired game, but it is a mechanic that people remember from Symphony of the Night. (The reviewer clearly remembered it, too, otherwise he couldn’t have mentioned it.) If you’re hoping to tap into players’ mental and emotional associations with that game, it’s not a puzzling choice at all.

I also recall a review of the Secret of Mana remake, which disappointed many people right off the bat by featuring bland and lifeless visuals that replaced the lush, gorgeous spritework of the SNES original. It was a video review. The reviewer was doing her best to give the game the benefit of the doubt. She wasn’t enjoying it, but she was trying to engage with it on its own merits.

She found a cannon, Secret of Mana‘s fast-travel system. On the SNES, this sequence was memorable and entertaining. Your party would climb into the cannon and get blasted into the air, the world would spin around beneath you, and then the camera would zoom in as you landed at your destination. Like everybody else who played the original, she was curious about how the remake would handle it. It turns out that it didn’t handle it; the entire sequence was omitted, and the game cut right from the cannon to her party arriving wherever they were going.

Her face fell. YouTubers exaggerate for effect constantly. Her disappointment, though, was clearly genuine.

These are two things that, in truth, are extremely minor aspects of their respective games. In one, it’s an inessential movement mechanic. In the other, it’s a non-interactive cutscene. Neither is likely to be cited as part of either game’s larger identity, and yet one new release feels far closer to its inspiration thanks to a decision to include it, while the other feels so much farther away thanks to a decision not to.

I am attempting here to illustrate the fact that these seemingly small decisions — what to include, what not to include — amount to more than it probably seems like they should. Timespinner feels more like Symphony of the Night than it otherwise would, specifically because it stops you in place while attacking. The Secret of Mana remake excises an unnecessary animation from its fast-travel sequence, and instantly feels miles removed from its source material.

Every game developer is allowed to make whatever decisions they’d like to make, but the differences in how a finished game feels are often far larger than the seeming size of the decision. As Tristram Shandy would have it, “Never, O! never let it be forgotten upon what small particles your eloquence and your fame depend.”

One tiny word, a line of code, a dead stop while swinging a weapon, a few seconds of air travel…small particles all, and yet they inform what we perceive as a game’s identity.

Let’s step into a different series, another one that is close to my heart: Fallout. Specifically, we’ll look at Fallout 3 and Fallout: New Vegas.

Bethesda took over the series beginning with 2008’s Fallout 3. Personally, I love that game; it’s one of my favorites full stop. Bethesda’s detractors, however, tend to claim something along the lines of, “It’s good, but it’s not Fallout.”

In a way, this makes a lot of immediate sense. The game is displayed in 3D rather than the top-down isometric perspective of Fallout and Fallout 2. It offers real-time combat as opposed to mandatory turn-based encounters. It requires players to traverse a large region instead of navigating quickly through empty areas from a map screen. The visual style is completely different. The game is primarily built and presented as a first-person shooter. It takes place in a different geographical region.

The list of superficial — and immediately noticeable — changes is a long one. Fallout 3 is indeed very different from its predecessors. It’s understandable that somebody who played Fallout and Fallout 2 would look at Fallout 3 and have the immediate reaction that it didn’t feel right.

But then 2010 came along, and we got New Vegas, which is now widely considered to be the best game in the series, even though it retained every single one of Fallout 3‘s deviations from the established formula. How is it possible that Fallout 3 is good but not Fallout, while the equally different New Vegas is the best Fallout?

Well, it’s easily possible; it’s just that the difference between what people perceive as “Fallout” and “not Fallout” goes beyond the superficial. They may not realize that — they may conclude, initially, that the shift in genre or perspective were the problem — but anyone who sees Fallout 3 as a failure for the series and Fallout: New Vegas as a success will have to accept the fact that the problem is something deeper and less easily articulated.

I won’t get too far into those games here — we’re going to talk about Mega Man 11 at some point, I promise — but it’s an instructive example. Ask someone why they feel New Vegas is the better game, and they will likely answer with something vague, such as “it has better writing” or “the quests are designed better.” People are of course allowed to believe those things, but they’re things that can’t really be measured outside of our own personal, internal scales. They’re also thoroughly debatable.

“Better writing” sounds clear enough, but it’s not that simple. In my opinion, for instance, New Vegas too often spirals into extended bloviation. Does the writing contain more interesting ideas than Fallout 3‘s writing? You bet. Is it also overlong, repetitive, and tiresome? Once again, you bet. Fallout 3 says less, but it says what it says more efficiently. New Vegas was in dire need of an editor. Is writing better when it achieves less, or when it overreaches?

Quest design can be considered in a similar way. Does New Vegas offer more quests and more ways to complete those quests? Without question. But is it also buggier to the point that quests break more often, fail to trigger, or close you out of certain solutions through no fault of your own? Without question. So what’s better? More options that often bug out, or fewer options that are more reliable? How could one even answer these questions?

I find the debate interesting. One of the most common reasons I see for people preferring New Vegas is that “the story is better.” I’ve asked a followup question about this a few times: What is it that you find interesting about the conflict over Hoover Dam? I’ve never gotten a direct answer. That is the story of New Vegas, but it’s not what people think of as the story of New Vegas because, in execution, it just feels like set dressing. New Vegas tells its central story so poorly that it doesn’t even feel like the central story. Many times, those who praise the story are trying to praise something else, but fail and fall back on the language that they actually have. Because they are unable to articulate how they really feel, they end up praising something else that they at least think they understand.

All of which is to say that everybody can “feel” when a game (or movie, or television episode, or novel) fits its series, and they can just as easily “feel” when it doesn’t. We will always have different opinions about which of those games or movies or episodes or novels are the outliers, but we all recognize them when we see them. There’s something that just doesn’t feel quite right. Sometimes we can articulate it. Sometimes we can’t. Other times we articulate the wrong thing just for the sake of articulating something.

We are allowed to get it wrong. We are allowed to misunderstand our own response to things. But it’s worth figuring out what it is that we’re attempting to say. It’s instructive to at least try to unravel our own thoughts. Maybe we get nowhere, but we might understand ourselves better in the process.

So, hey, great. But what makes a Mega Man game a Mega Man game?

On the surface, there’s an easy answer: You are offered a selection of levels and can go wherever you want. You fight difficult enemies in punishing environments. You square off against a boss and take its power, which prepares you better for whichever stage you select next.

And yet, that’s not right, because I’ve just described around 50 indie games that do the exact same thing. (I’ve not been the only one exploring my love of Mega Man in the time since 2010.) Indie games and fan games aren’t Mega Man games, even if they do all of the things I just listed. Therefore, whatever makes a Mega Man game a Mega Man game has to amount to more than an overall approach, just as Fallout wasn’t only defined by its perspective or combat mechanics.

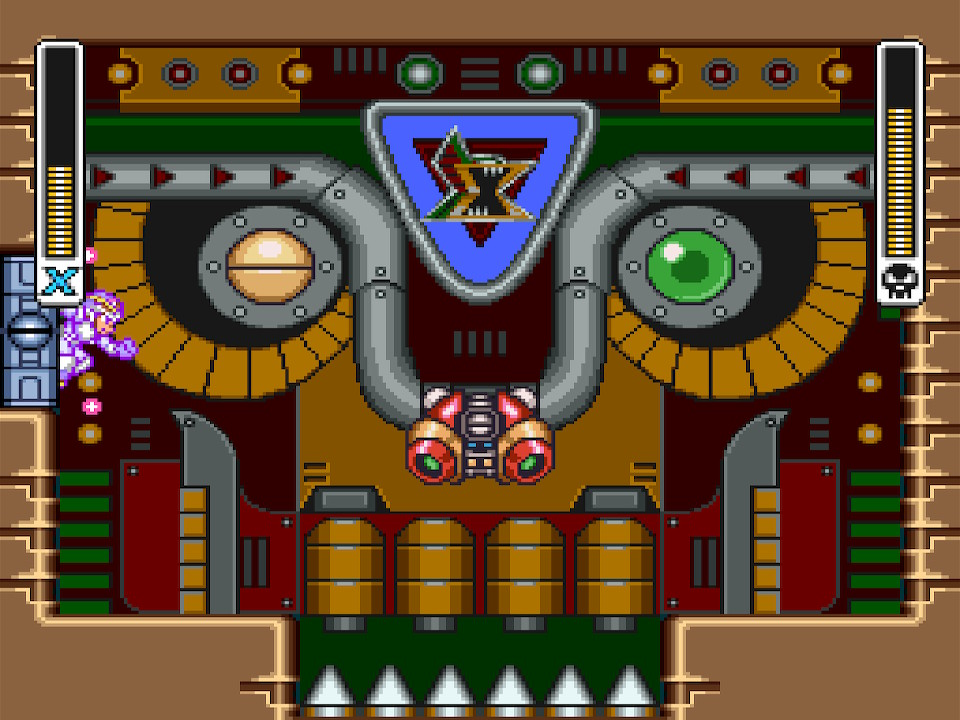

Okay then. Do Mega Man games need to be 8-bit? Of course not; Mega Man 7 feels like Mega Man. Do they need chiptuned disco beats? No; the piano-heavy alternate soundtrack for Mega Man 11 is one of this game’s few true highlights. Do they need eight main stages? Well, the first game had six, so probably not.

We can make a list of all of the things that we think add up to create a Mega Man game, and we’ll find an exception to every one them. Each game adds and removes features to the point that all we’re really left with is…Mega Man himself, and clearly that’s not the answer; would a game of checkers with a Mega Man avatar become a Mega Man game?

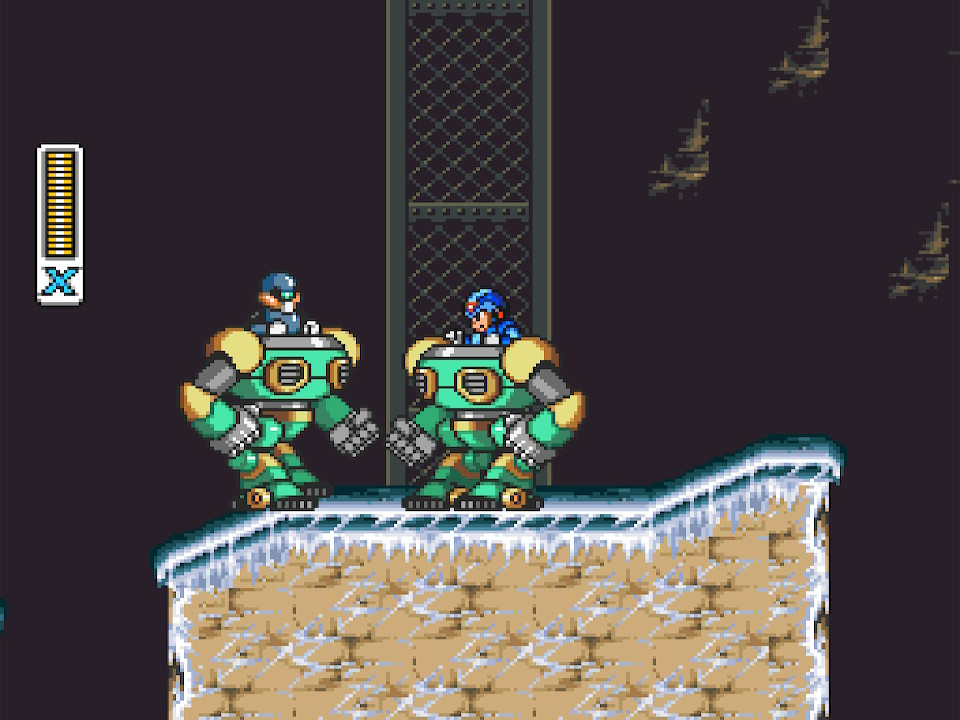

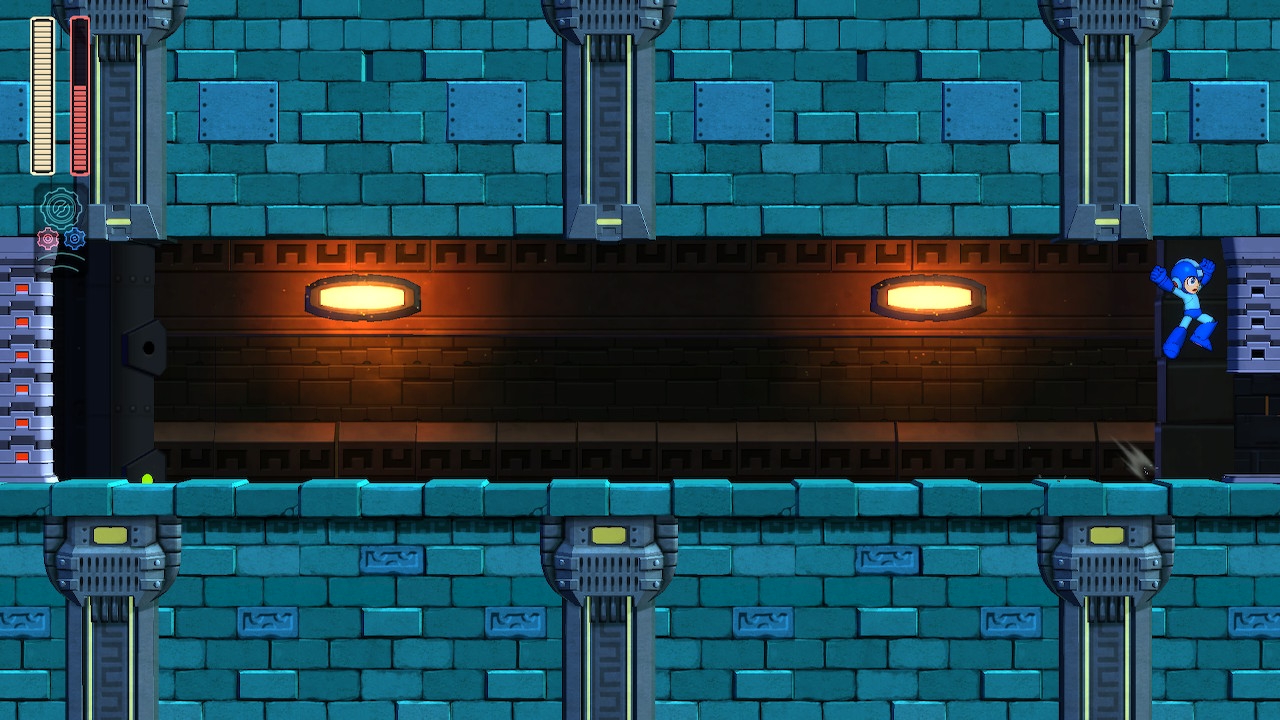

What is a Mega Man game then? I don’t have an answer. And yet, I do have an answer that I know isn’t a valid one: In a Mega Man game, you freeze in the air when you hop through the boss gates.

Now, of course, that’s utter shash. There’s more to a Mega Man game than that. And yet, with it missing in Mega Man 11, I found myself fixating on its absence. And, once I did that, I started to notice all of the other ways in which the game felt off.

The lack of freezing in the air through the boss gate transitions is this game’s missing cannon blastoffs. It’s this game’s lack of coming to a dead stop while attacking. It’s this game’s “bad writing.” It’s the thing we focus on because we have so much to say, but can only understand one small piece of it. It’s emblematic of our overall disappointment, and it’s what we talk about not because it’s the best way of making our point, but because it’s the only thing we understand well enough to confidently explain.

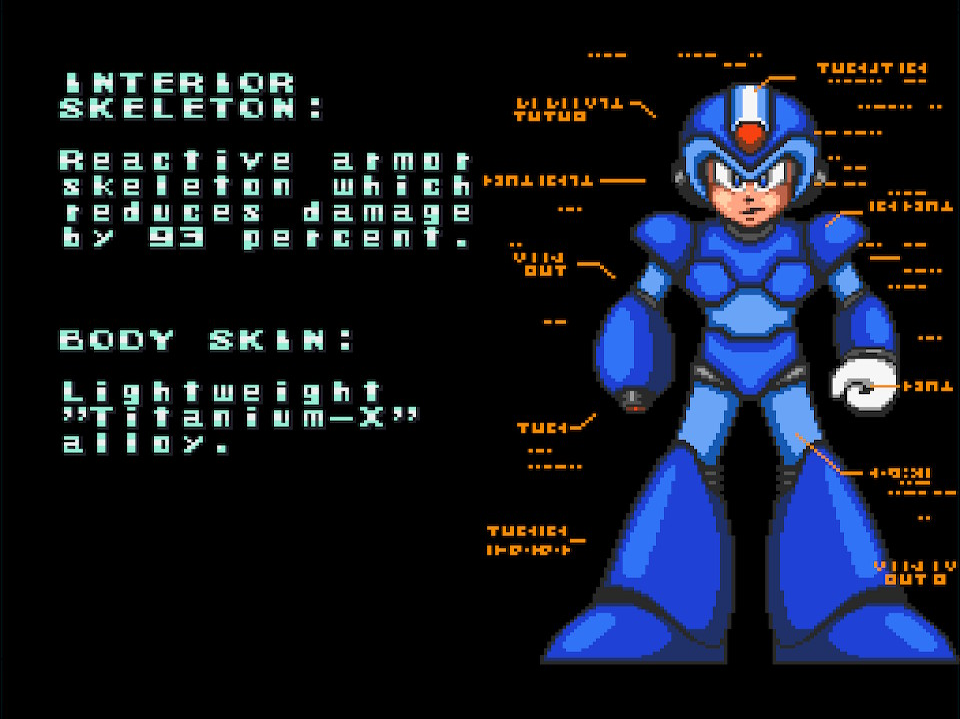

Jumping into the boss gates and hovering there as you float into the next room is a part of what makes Mega Man games feel like Mega Man games. Ditto the ability to fire your Mega Buster just before you touch the door, resulting in an even cooler sprite. It hangs there on your screen as a reward for hitting those two buttons in the correct order with the correct timing, allowing you to confront the boss with genuine retro flair.

Doing this isn’t difficult, to be clear. It’s less a challenge than it is a simple, satisfying flourish with which to end a long, arduous trek through the stage-long gauntlet.

You’ve made it. You’ve succeeded. The big duel is about to start, and you get to assert yourself with a victory pose. It’s the equivalent of a wrestler’s big entrance. You conquered this level, and now you’re going to boot its boss right out of it.

It’s not necessary. Nothing is necessary. But it makes Mega Man feel like Mega Man.

And so when Mega Man 11 decided to just drop you to the ground after its boss gate opened…well…that’s okay, right? It’s minor. It doesn’t really make a difference. Even the bad Mega Man games do the fun boss gate thing, don’t they? It’s not a seal of quality or anything. Who even cares?

I care. Because at the end of every stage I was wired to leap into that boss gate and draw my Mega Buster, and at the end of every stage I fell right to the ground and then walked through it as though what was happening was not important at all.

Boss gate after boss gate rejected my flourish. The rejection adds up. (I’m a writer, so I know this.) As it does, I’m forced to wonder what it is, exactly, that Mega Man 11 is doing. It doesn’t have to do everything that the previous games did (no Mega Man game does everything that the previous games did), but what is it doing instead?

The cynic in me immediately wishes to argue that it’s doing very little, but it does have a handful of major innovations that are worth discussing.

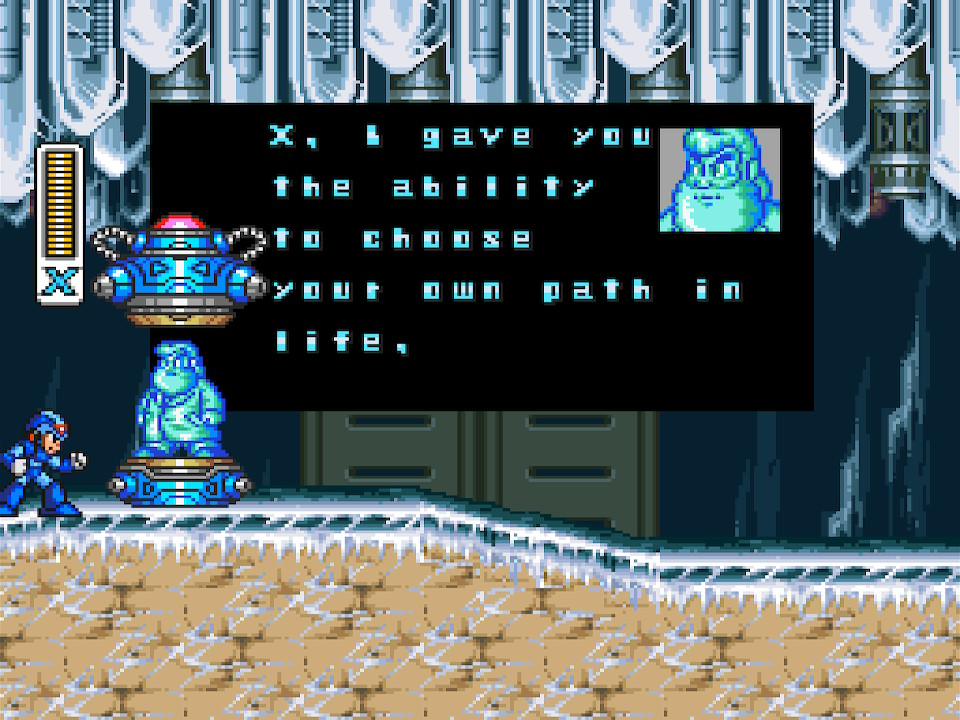

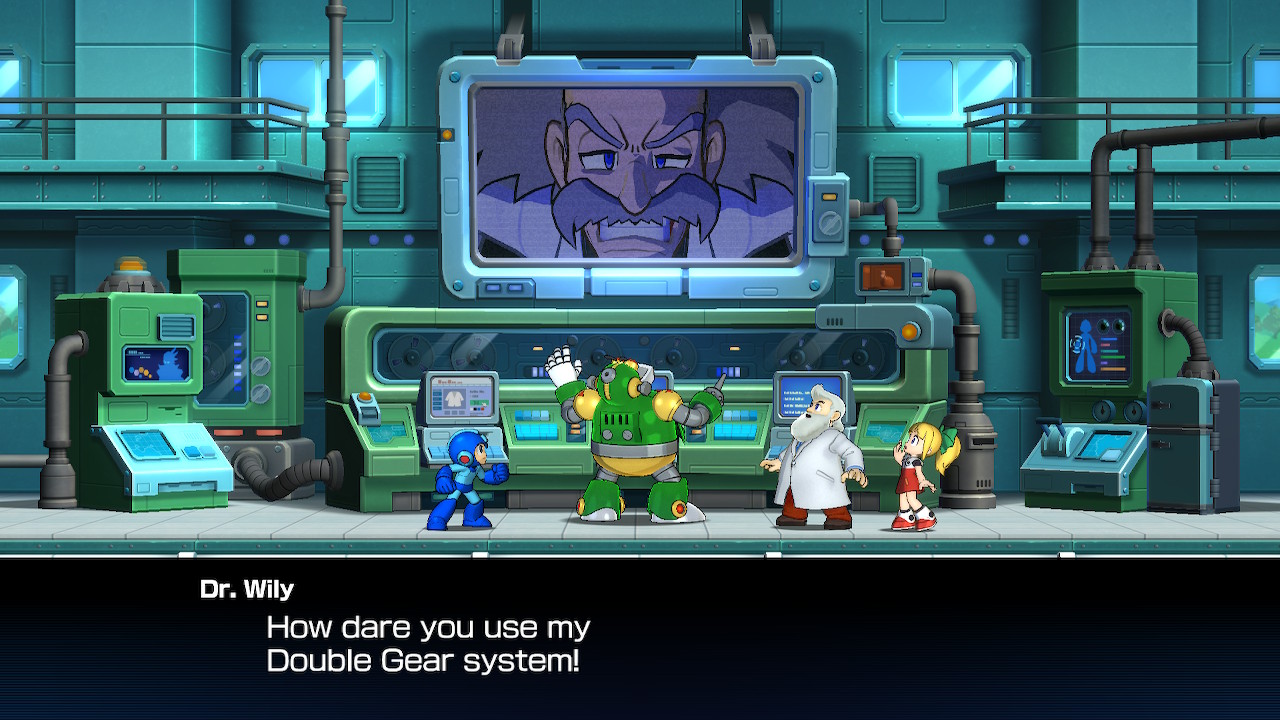

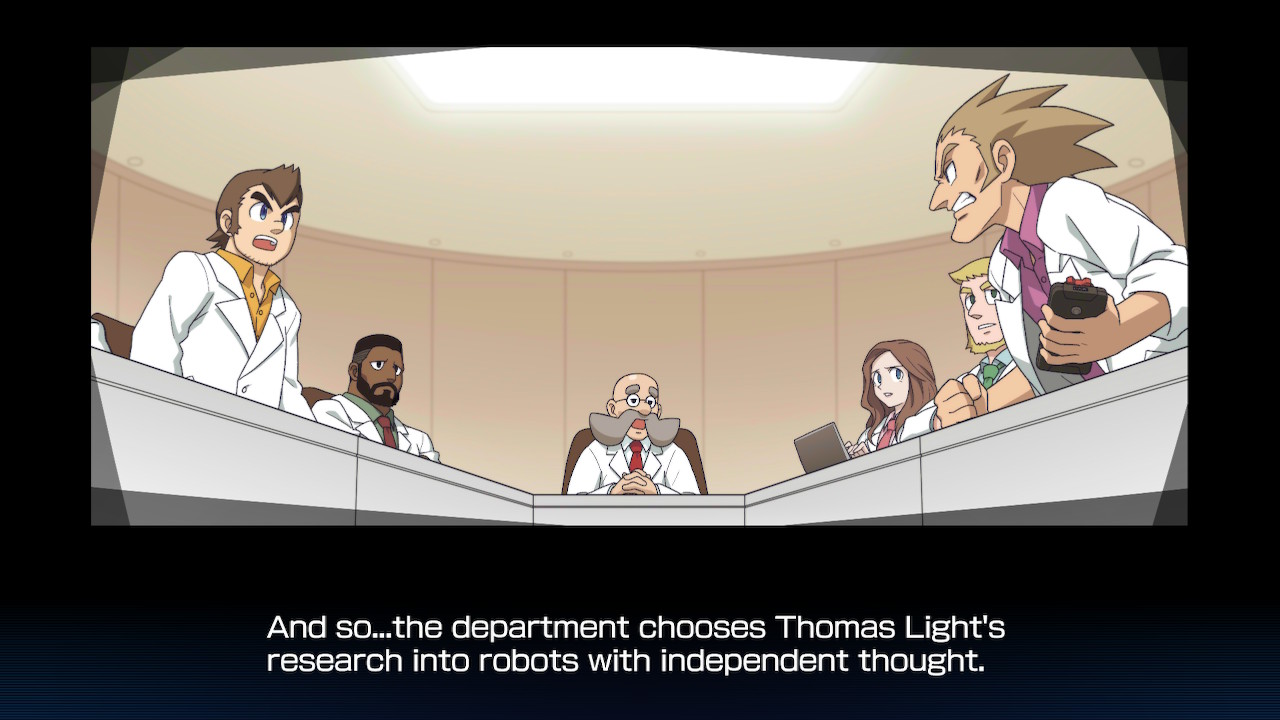

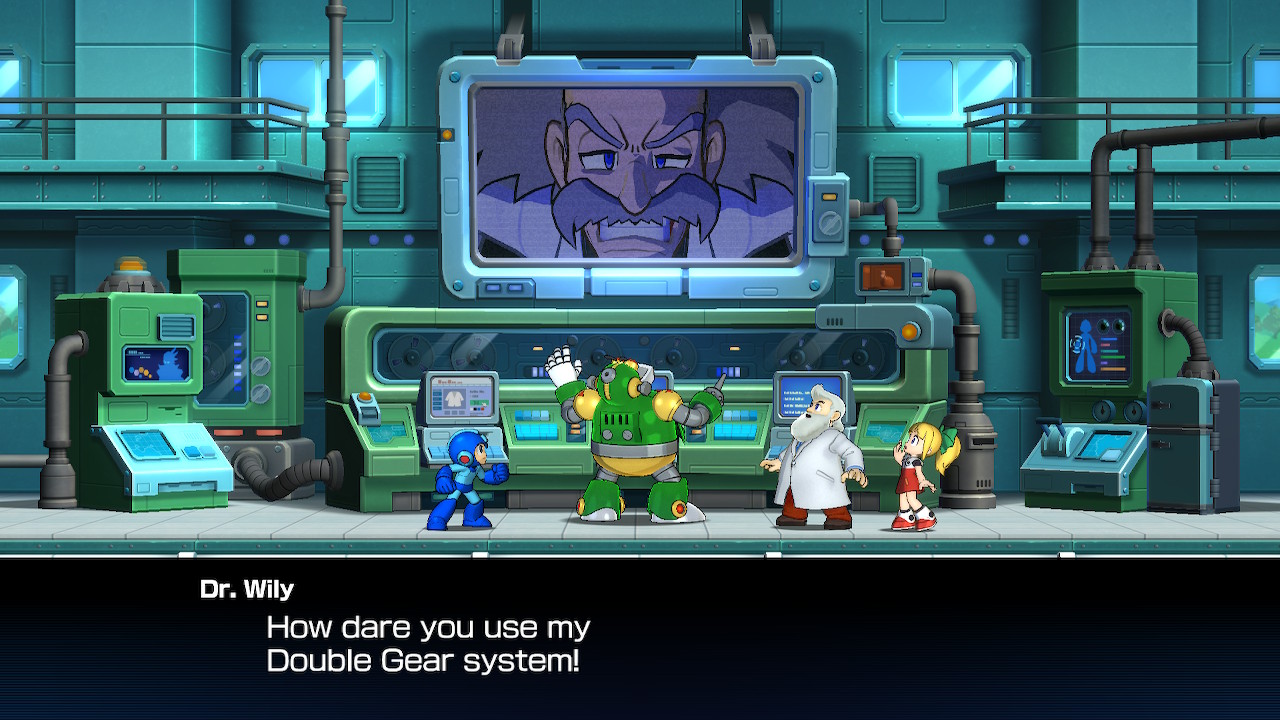

There’s the focus on story, most obviously. A few previous games — most notably Mega Man 8 — had an interest in crafting an actual narrative, but all of them boil down to Dr. Wily going mad again and Mega Man having to off his minions, one by one, before storming his base and stopping him. Mega Man 11 goes a little bit farther this time around, though, giving us significant series backstory in the process.

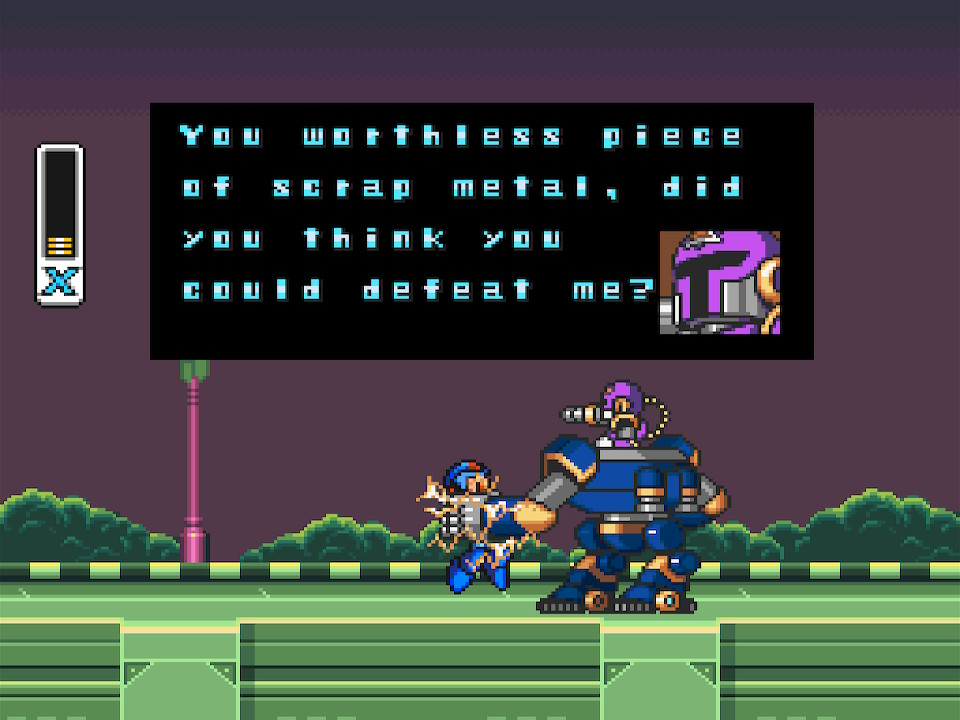

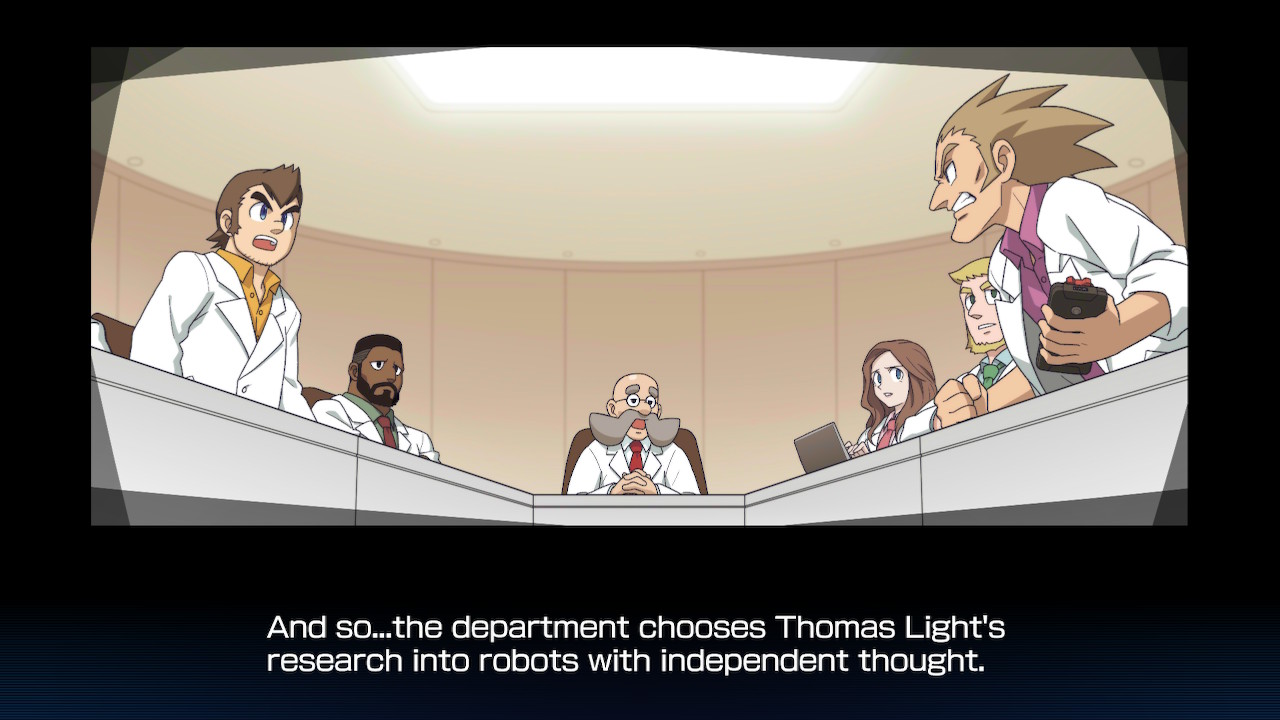

We see Dr. Light and Dr. Wily in their university days, arguing with each other about the future of robotics. Dr. Light wants to research independent thought and allow robots to make decisions for themselves. Dr. Wily wants to…well…basically arm them to the teeth and make them go crazy. For some reason, the other researchers side with Dr. Light, and Dr. Wily’s research is cast aside in disgrace.

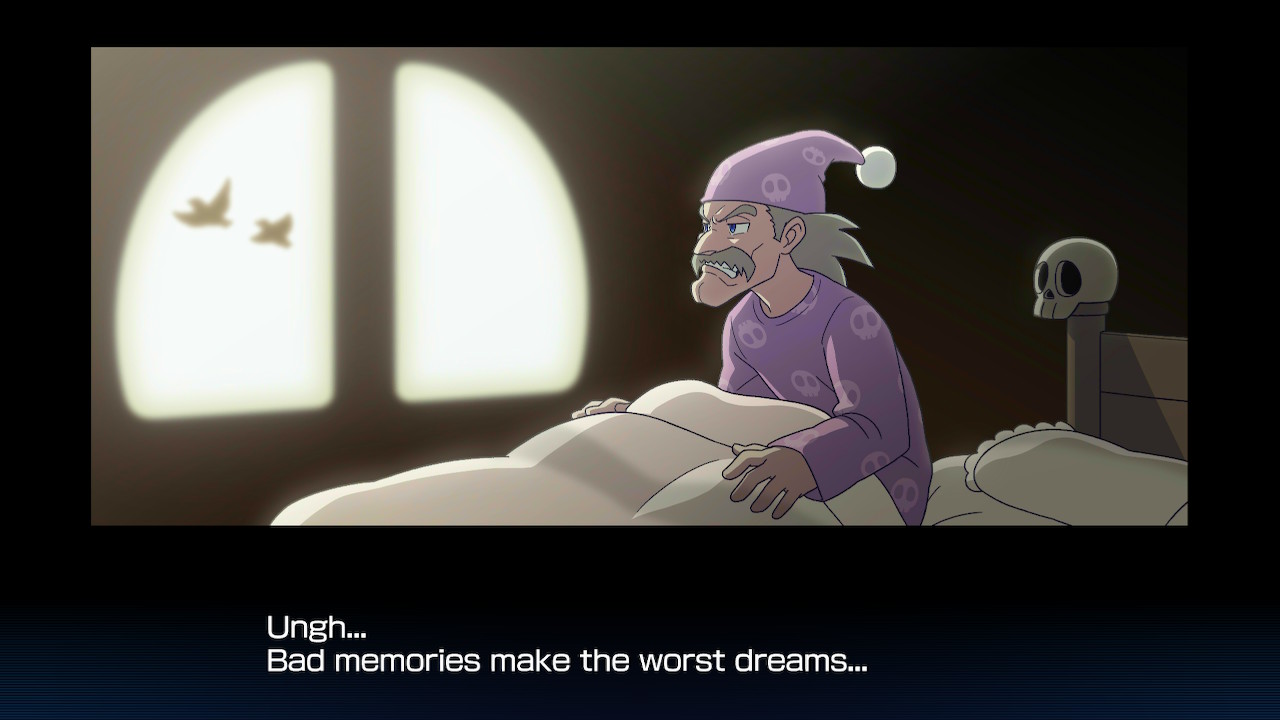

In the present, Dr. Wily wakes from this nightmare / flashback — wearing skull pajamas, in one of the game’s few moments of cute creativity — and remembers the Double Gear System he was working on.

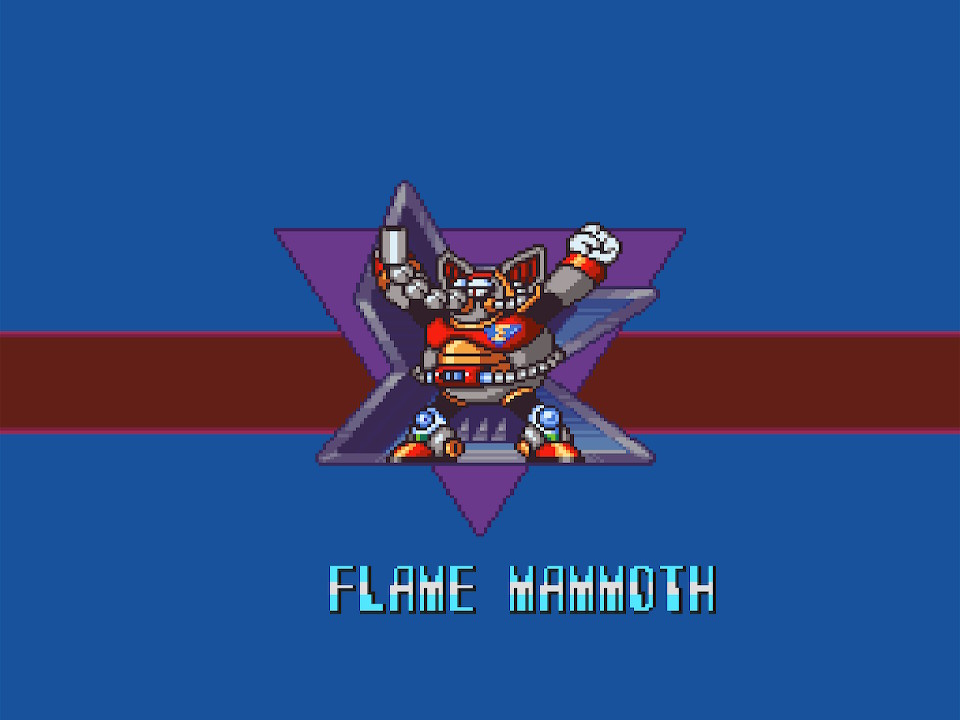

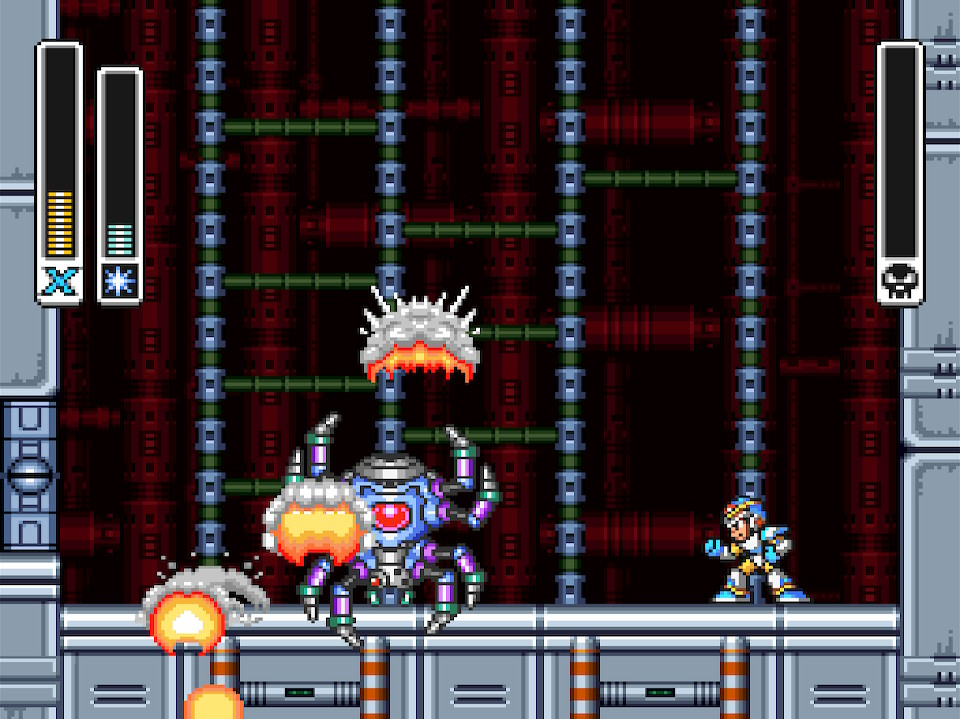

What is the Double Gear System? That…doesn’t really matter or make sense. Basically, it allows robots to either temporarily beef up their offense or increase their speed as they see fit. Wily hotwires eight Robot Masters, installs the Double Gear System in them (I think…more on that in a moment), and…nothing changes, really.

The Double Gear System does have an impact on gameplay, but not a major one. Mega Man is outfitted with it, so that he’ll be able to square off against Wily’s powered-up goons.

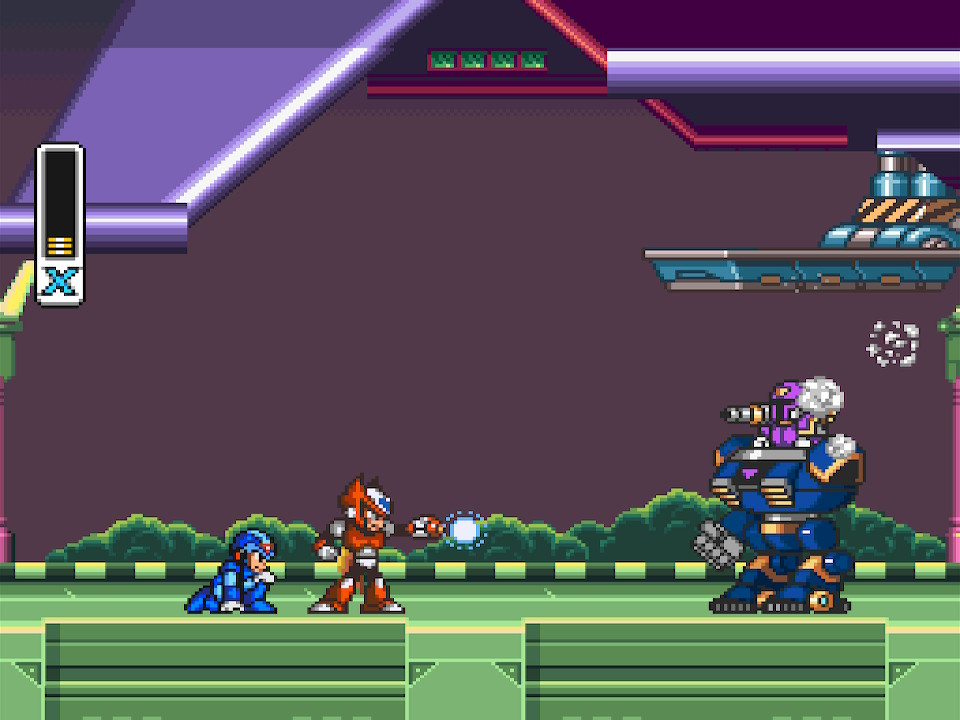

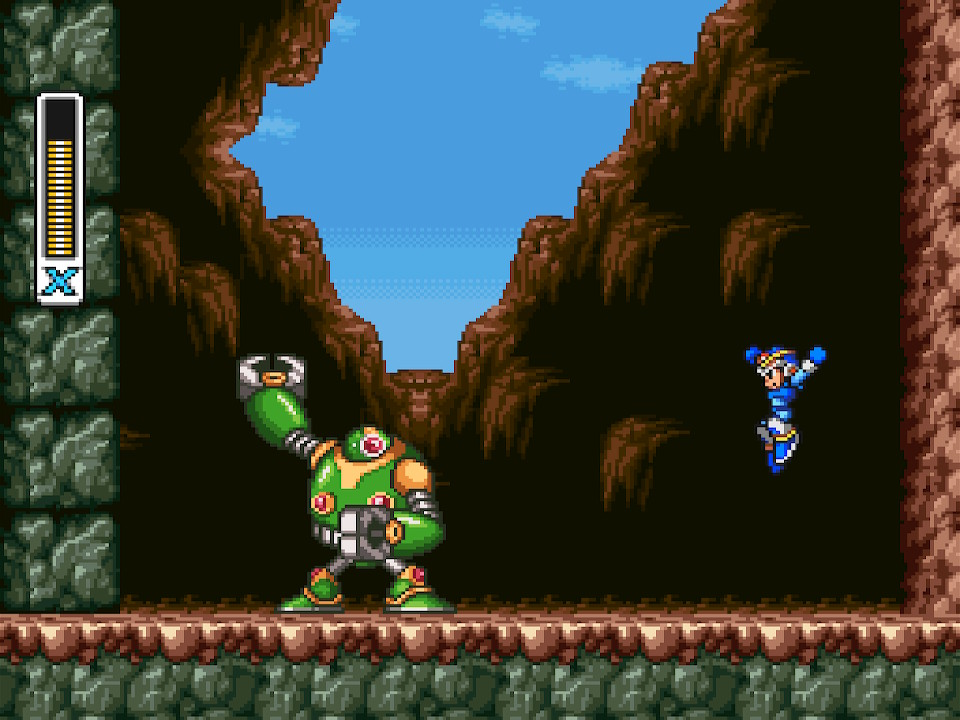

Dr. Light tells Mega Man at the beginning that he’ll be crushed like a bug if he doesn’t use the Double Gear System himself, but in reality the Double-Gear-powered-up Robot Masters are no more difficult or complex than Mega Man bosses usually are. Sure, as Mega Man, I can now use these new functions myself, but I never need to use them, so it feels pretty silly to frame them as being essential to my success.

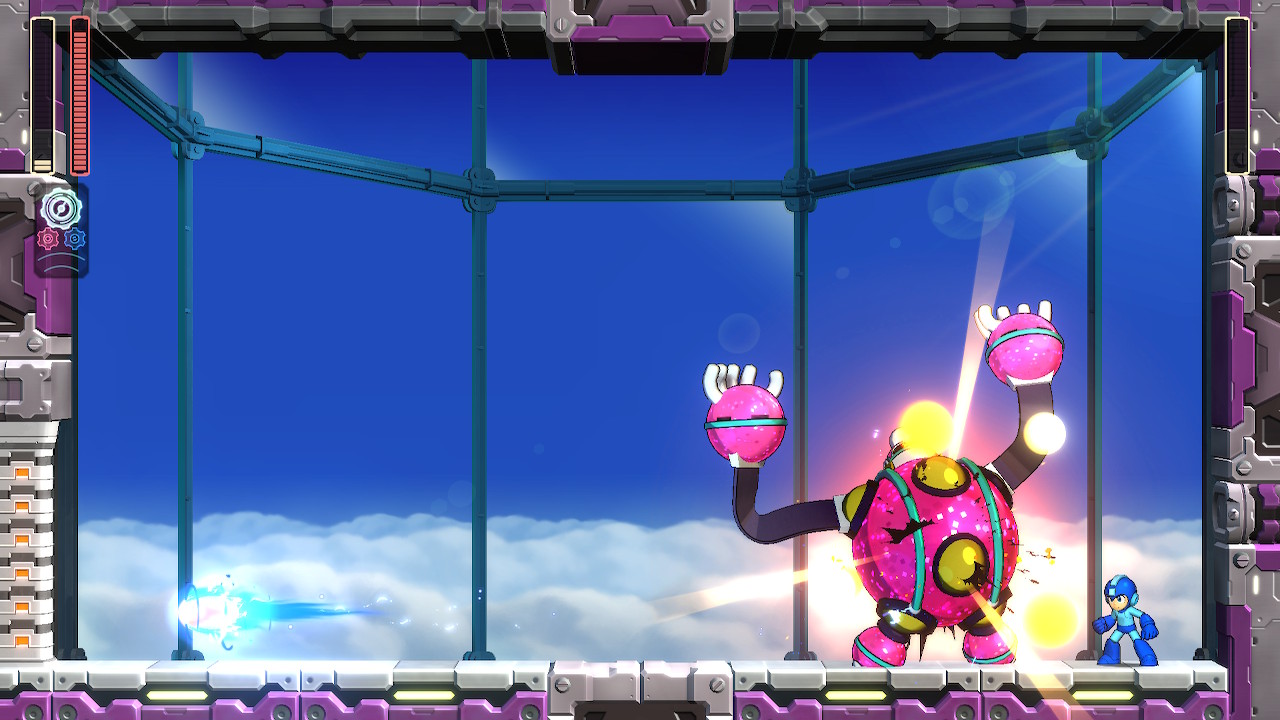

The Robot Masters, I think, are ostensibly meant to have access to both functions of the Double Gear System, but in practice they each only use one. Reduce their health enough, and Blast Man, Block Man, Impact Man, and Torch Man will activate the Power Gear, while Acid Man, Bounce Man, Fuse Man, and Tundra Man will activate the Speed Gear. No matter which of these they use, it just amounts to a new attack or two for each boss. (There’s a notable exception, but we’ll get to that.)

That’s nothing special, to be clear. Bosses — in this series and certainly elsewhere — get new attacks all the time. The Double Gear System is presented as a huge complication for the narrative and the gameplay, working hard to justify something that hasn’t needed to be justified for decades. They aren’t more dangerous attacks, either; they’re just different attacks.

Mega Man gets to use both the Power Gear and the Speed Gear, and I like that in theory. Giving Mega Man and his enemies the same big new ability could have led to something interesting. It could have changed, in some way, the entire feel of Mega Man 11 and helped it to stand out as an individual game rather than just the latest entry in a long-running series. In practice, it again changes nothing and Mega Man 11 fails to stand out at all.

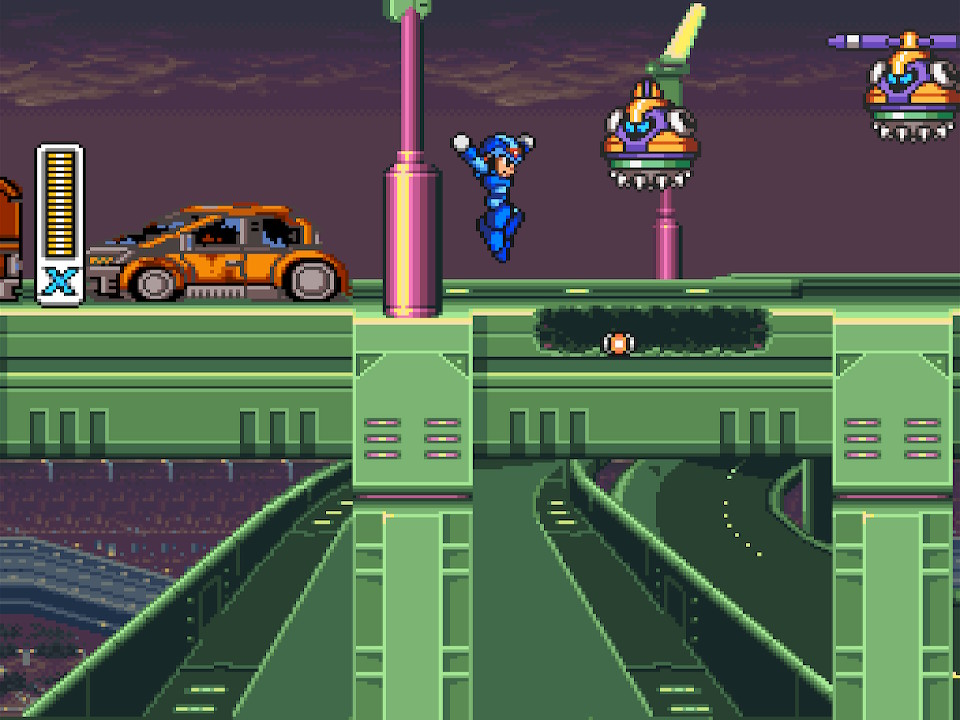

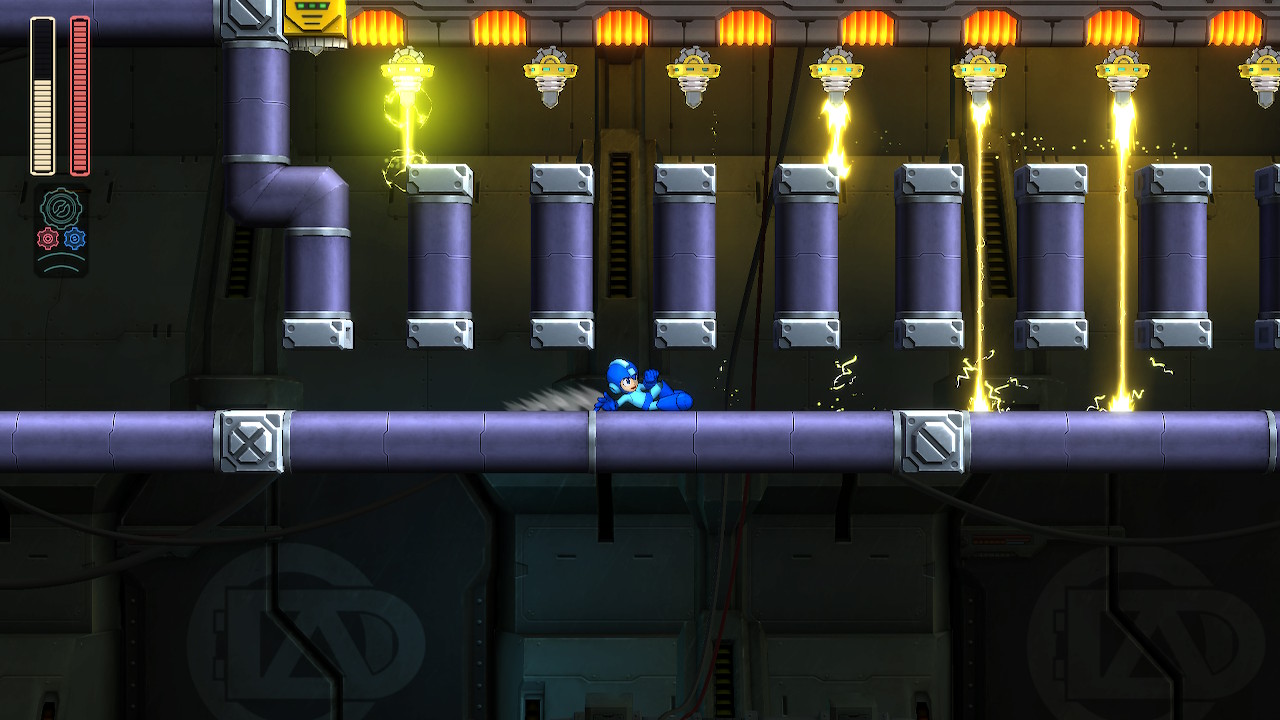

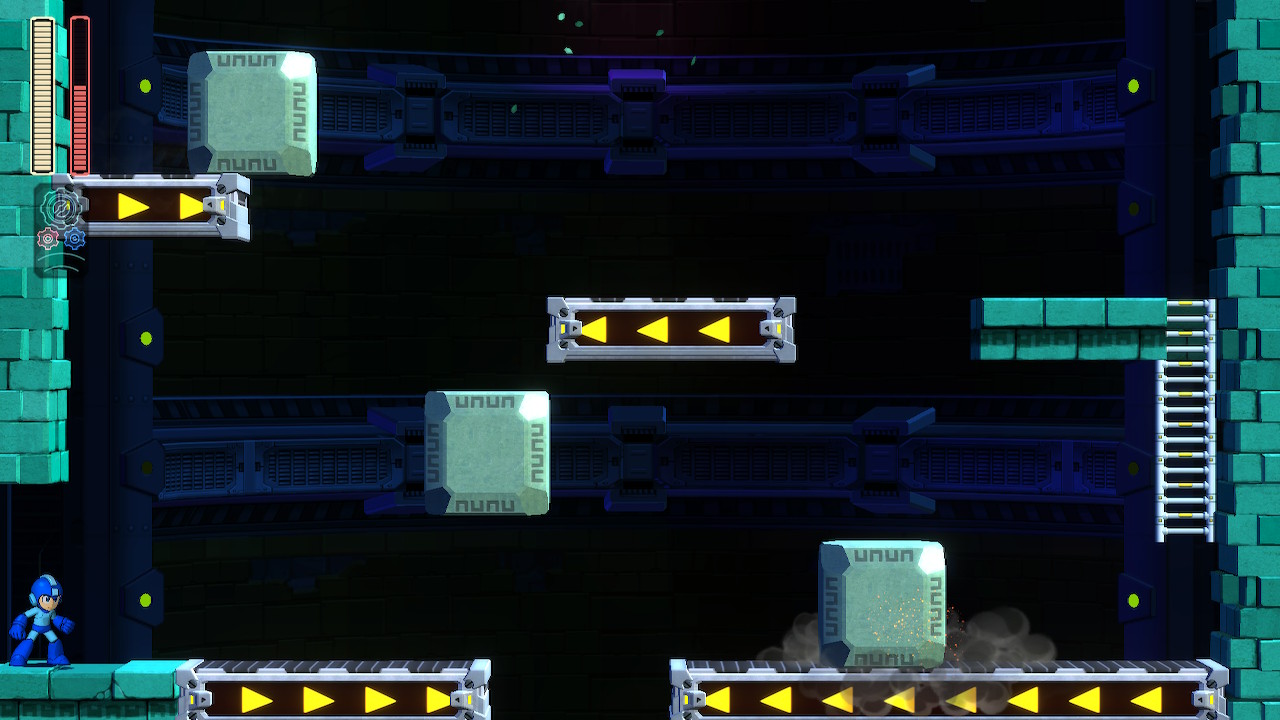

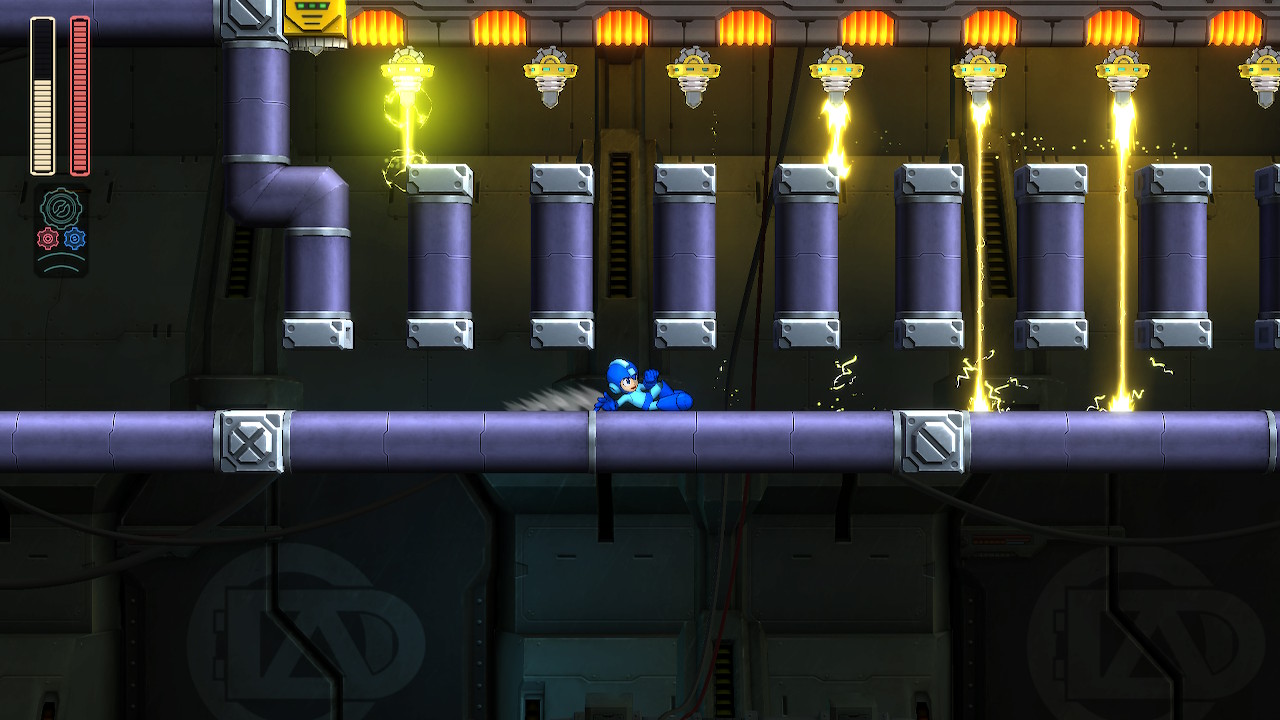

The Speed Gear is by far the more useful of the two. When you turn it on, everything slows down. This allows you to make tricky jumps onto and off of falling platforms, for instance, without having to rely on impossibly quick reflexes. It could also allow you to weave your way comfortably through a hail of bullets, or slow down an approaching death trap to give you more time to think. It’s a solution to a problem that the series never really had to begin with, but it’s at least something interesting to play around with, and the game invents a few decent sequences that justify its inclusion. We’ll get to those.

The Power Gear, though, is fucking worthless. And I mean that literally. It has no value whatsoever to the game or to players.

The Power Gear is meant to power up your projectiles. That’s fine; having some kind of option for turning our weak basic shots into more powerful blasts is a nice concept. And it was indeed nice that we were finally allowed to do that…back in Mega Man 4.

That game had the elegant, natural idea to let the player hold down B for a short period to build up some extra power. Release the button and Mega Man would fire a larger, more damaging shot. It worked well. Holding the button down to increase power made intuitive sense. The delay before firing meant that it couldn’t be abused. The necessity of charging it first meant that you had to aim your shot carefully, lest you miss your target and waste your shot. All of that worked great.

The Power Gear is that, but as a toggle. It offers nothing that a charge shot doesn’t offer, but you can abuse it and you no longer have to think about aiming, because you can fire as much as you like, which also removes the risk/reward balance of the charge shot. That’s fine if firing blindly is what you prefer, but the default Mega Buster already allows you to do that. The Power Gear still doesn’t make anything easier, in that case; it just makes enemies require fewer shots. It doesn’t change the way you play the game or accomplish your goals at all.

The truly strange thing is that the charge shot was missing from Mega Man 9 and Mega Man 10, meaning that Capcom made the conscious choice to bring it back for Mega Man 11, and then also gave us a new mechanic that did the same thing. If the charge shot were still missing, the Power Gear would make sense; it would be understandable as a replacement for a mechanic that we lost several games ago. Instead, it’s a less-elegant, less-intuitive, less-interesting way to achieve the same thing we can already do. What’s the point? Mega Man 11 decided to fix what had never been broken…while still leaving the previous, better fix in place. It’s baffling.

In a way, the Gears are representative of the best and worst impulses behind Robot Master weapons in general. The Speed Gear is like a good Robot Master weapon, because it changes the way in which you interact with the world, enemies, and obstacles around you. The Power Gear is like a bad Robot Master weapon, because it just changes the shape and damage of your projectiles.

Even then, the Gears fall down, because Robot Master weapons are earned. If you want one, you have to fight for it and take it. The Gears, by contrast, are given to you at the outset of Mega Man 11. They’re part of your default moveset, which implies some degree of significance.

In reality, though, you’ll try the Speed Gear and say, correctly, “I’ll rarely need this.” Then you’ll try the Power Gear and say, correctly, “I can already do this.” It’s disappointing when Robot Master weapons are rarely useful, but for core mechanics of the game to be rarely useful, that’s more than disappointing. That’s downright bad design.

Speaking of Robot Master weapons, it’s worth pointing out that holding the fire button does not charge those up, while the Power Gear does. That’s a fair distinction, but it’s worth remembering that the Mega Man X series had demonstrated eight-ish times over by this point that holding the fire button to charge its special weapons worked and felt just fine. There’s no benefit to implementing a clumsier system than what fans were already used to using.

And forgive me for harping on about this, but the Power Gear is rendered even more worthless by the fact that the charge shot can be used any time at all, while the Gears draw energy from a dedicated meter. You can only use the Gears briefly; keep them active too long and they overload, causing you to be unable to use them again until they cool down. That’s fine, but they overload so quickly that you end up having to manage their on-off switch more than you’re actually firing or platforming.

Using the Gears is a nuisance because you can’t just flip one on and do what you want to do; you have to flip one on, do some portion of what you want to do, flip it back off, wait for it to cool down, flip it back on, do more of what you want to do, flip it back off, and repeat until you’re done. It’s annoying, more trouble than it’s worth, and in the time it takes you to manage the Gears designed to help you, you could simply learn how to accomplish whatever you’re trying to do without using them at all.

Again, for an optional utility or Robot Master weapon, that’s fine, if disappointing. For a core mechanic framed as the defining new aspect of Mega Man 11, it’s just evidence that Capcom never figured out why either of these things should matter. The increased focus on narrative makes sense now; without the story reminding us many times over of how important the Double Gear System is, we’d never arrive at that conclusion ourselves.

Mega Man 11 does introduce little pickups that enemies can drop, which will immediately cool your gears down, but those are dropped randomly, just like health and weapon energy, meaning that you can’t rely on getting one when you need it, further discouraging anything but the most conservative use of the Gears. And if you aren’t actively using a Gear that very moment, snagging one won’t help with anything, because the cooldown happens automatically.

The pickups mean nothing unless you’re actively using the Gears, but you can’t count on them dropping often enough to justify actively using the Gears. How did nobody identify this as a problem?

Fortunately, the Double Gear System isn’t the only innovation that Mega Man 11 brings to the formula. It’s the most significant and disappointing one, but there are a few more.

For starters, you have dedicated buttons for the Rush Coil and Rush Jet. I like that. Those aren’t weapons, really, so having to select and “fire” them as you did in previous games never felt exactly right. Allowing them to be summoned with one press of a single button while you are doing whatever else you need to do is a great way of keeping things moving. That’s an extremely small step forward, but it’s still welcome.

Then there’s the fact that the charge shot now forces enemies to drop their shields, letting you attack them openly. This is…okay. Part of me likes the idea, but the rest of me realizes that this just removes the care and timing necessary in previous games to defeat shielded enemies. In those games, you’d have to avoid their attacks and bide your time until they became vulnerable, then sneak in a hit or two and repeat the process. It was…y’know…a game.

Now, you just have to knock their shield away with a charge shot and fire a couple more quick pellets. That’s it. No timing, no thought, no brainpower. And since the charge shot will necessarily be your first shot — you need to power those up, remember; you can’t just fire one off whenever you feel like it — that means that your very first shot will always create an opening for more. At that point, why bother giving us shielded enemies at all?

Another innovation is that Mega Man gets different helmets and accoutrements while using special weapons. It’s a cosmetic tweak only. It’s fine, but I think changing his suit’s color was a perfectly reasonable way of letting players see at a glance what weapon was equipped. I don’t think having a bunch of accessories hot-glued to him makes things any clearer.

Also, speaking of special weapons, I love the idea of making the weapons demonstrations interactive. That gives us an opportunity to play with our new toy without having to worry about ammunition or damage.

However, those screens also contain instructions and button commands, which makes the whole thing feel cluttered and confused. The game inundates players with text that explains everything, while giving them at the exact same time the chance to experiment and figure it out for themselves. Either approach can work, but doing both at the same time makes it feel like nobody cared enough to make a decision.

If you’re tired of listening to me complain, I’ll say something nice: I think Mega Man 11 implemented some kind of tweak that makes it less likely for you to fall off the edge of a platform when you get knocked back. Sometimes you do fall, but the game seems to be a bit more forgiving and give you a little more grace than previous games did. That’s a positive change. Look at me being positive.

All of this probably sounds like I dislike Mega Man 11 because it’s different, but it’s not that. Every Mega Man game is different to some extent, in its own way. Every Mega Man game does something unique. Every Mega Man game experiments.

Sometimes those experiments work. Often, they don’t. No matter what, I try to engage with them on their own merits, and I do my best to appreciate each game for what it is rather than what I would like it to be. Sometimes, of course, I come away still not liking the game. Other times I’ll feel that the game is flawed but gets enough right that I appreciate its effort.

No matter what, however much or little a single game tries to shake up the formula, I want to treat it fairly. I replay these games many times. I give them every opportunity to either win me over or to charm me. So, ultimately, no, I don’t dislike Mega Man 11 because it’s different. I dislike Mega Man 11 because it’s pretty bad.

In fact, let me prove that I’m willing to accept things that are different. And I’ll do it by complaining some more!

See, the soundtrack to this game is awful. Not just disappointing by Mega Man standards — which would be easy, because the soundtracks in this series are some of the best in all of gaming — but actively lousy. Every single song sounds like…nothing. It’s just endless, dreary electronic swirling. It’s the aural equivalent of caulk.

It honestly sounds as though somebody told the composer, “Mega Man has electronic music,” and she took that as literally as possible and no further. The music is flat, droning, and thoroughly devoid of personality. That’s something I could never say about even my least favorite soundtracks in other Mega Man games. (Well, we’ll see; I may take that back if I ever cover Mega Man X.)

But here’s the thing: As a pre-order incentive for the game (and, I believe, free DLC now, so grab it if you can), there was an alternate soundtrack. It’s called The Wily Numbers for reasons I can’t fathom, but the compositions are performed by live instruments and musicians instead of whatever flatulent robots were enlisted for the main game’s soundtrack.

…and it’s great. It sounds nothing like a Mega Man soundtrack, at all. It’s piano heavy. It feels organic and lively in a very human way as opposed to funky or danceable, which is how the soundtracks usually feel. It sounds like a bunch of musicians in a studio jamming along to one basic concept or another and it’s great. What’s more, it feels great while playing. It shouldn’t. If you’d asked me if a jazzy piano soundtrack were the right approach for Mega Man, I’d have said no…but this proves me wrong. It’s excellent. It fits. It’s different…and I love it.

Still, that only puzzles me more. These songs have melodies that work in service of their stages, and they’re all present in the main soundtrack, but they’re buried beneath groaning digital nonsense. The Wily Numbers songs let those melodies breathe and flourish. The same melodies are there in the originals, but are either impossible to hear or difficult to focus on. Either the performance or the production renders them inert.

The Wily Numbers brings them back to life. The icy dance of Tundra Man. The murky bubbling of Acid Man. The campfire march of Torch Man. All of it is excellent, and all of it is based on compositions in the main soundtrack that feel so empty and dry. This means that the composer — Marika Suzuki — did indeed compose songs that work well with every stage…but the execution of the main soundtrack is, for some reason, just fucking dismal.

I don’t know if that’s her fault. I’m willing to guess that it’s not, now that I’ve actually heard how these compositions can sound, but somebody somewhere went out of their way to package the game with the worst possible interpretation of every last one of them.

As such, I can’t even play Mega Man 11 with the standard soundtrack. It’s nearly unlistenable. With the Wily Numbers versions, though, I not only get some truly excellent music, but I get a glimpse of an exciting new direction that soundtracks for future Mega Man games could take. Seriously, even if you have no interest in this game, I’d recommend listening to all eight of the Wily Numbers tracks. They’re gorgeous.

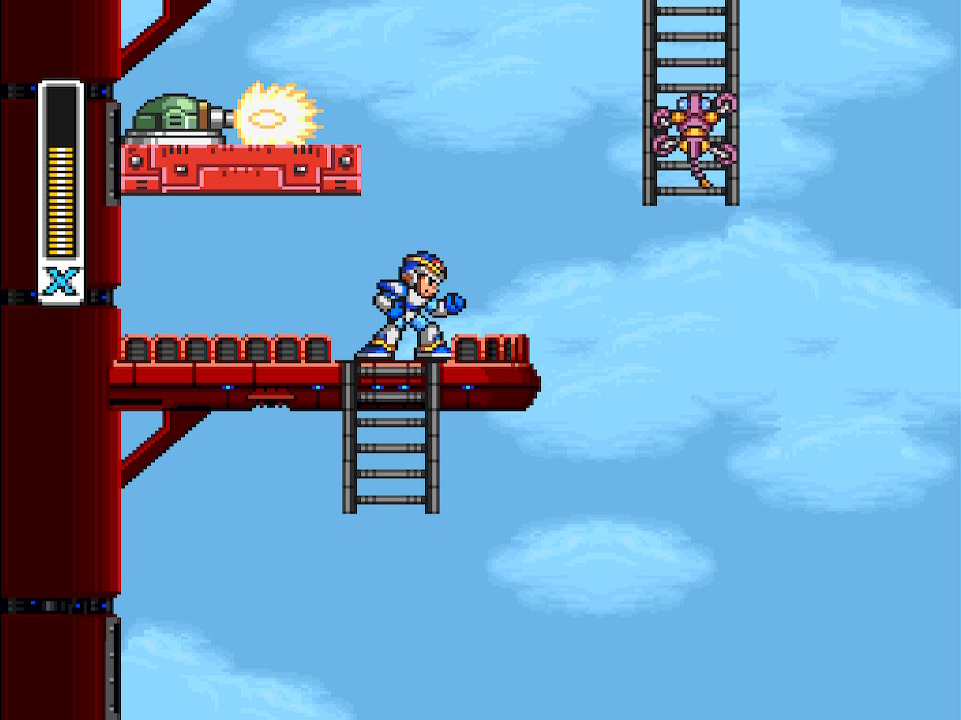

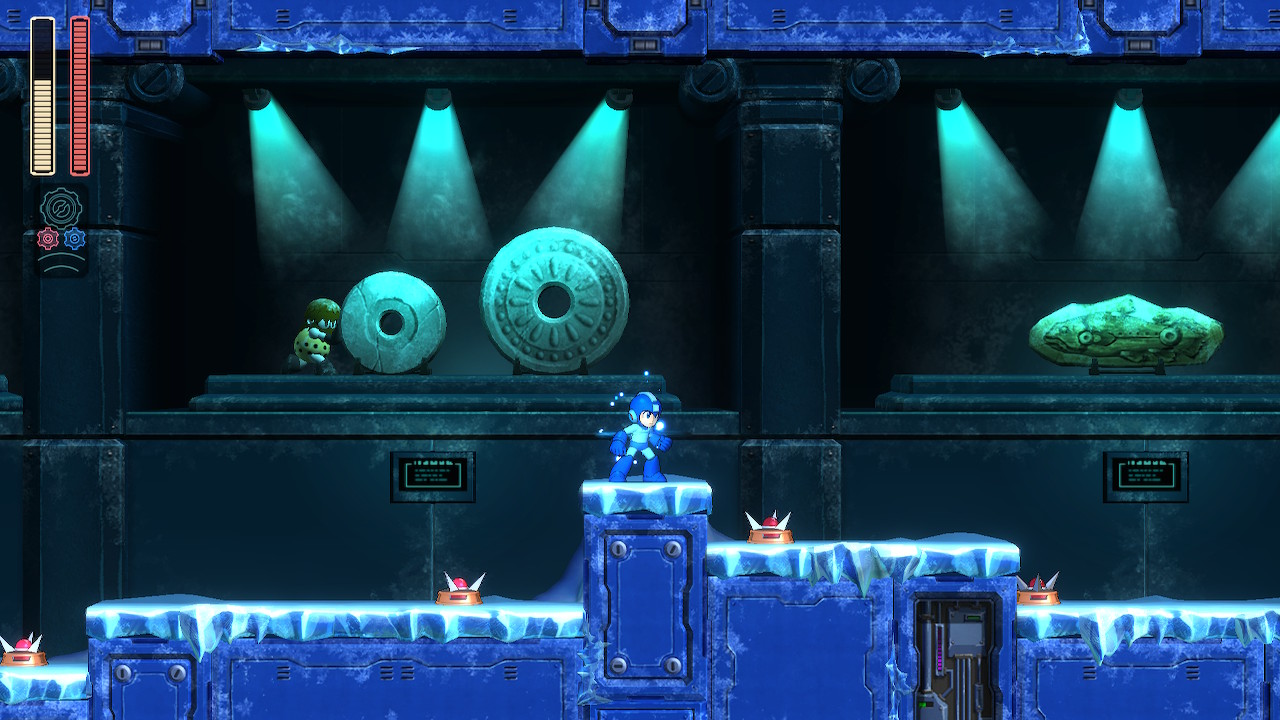

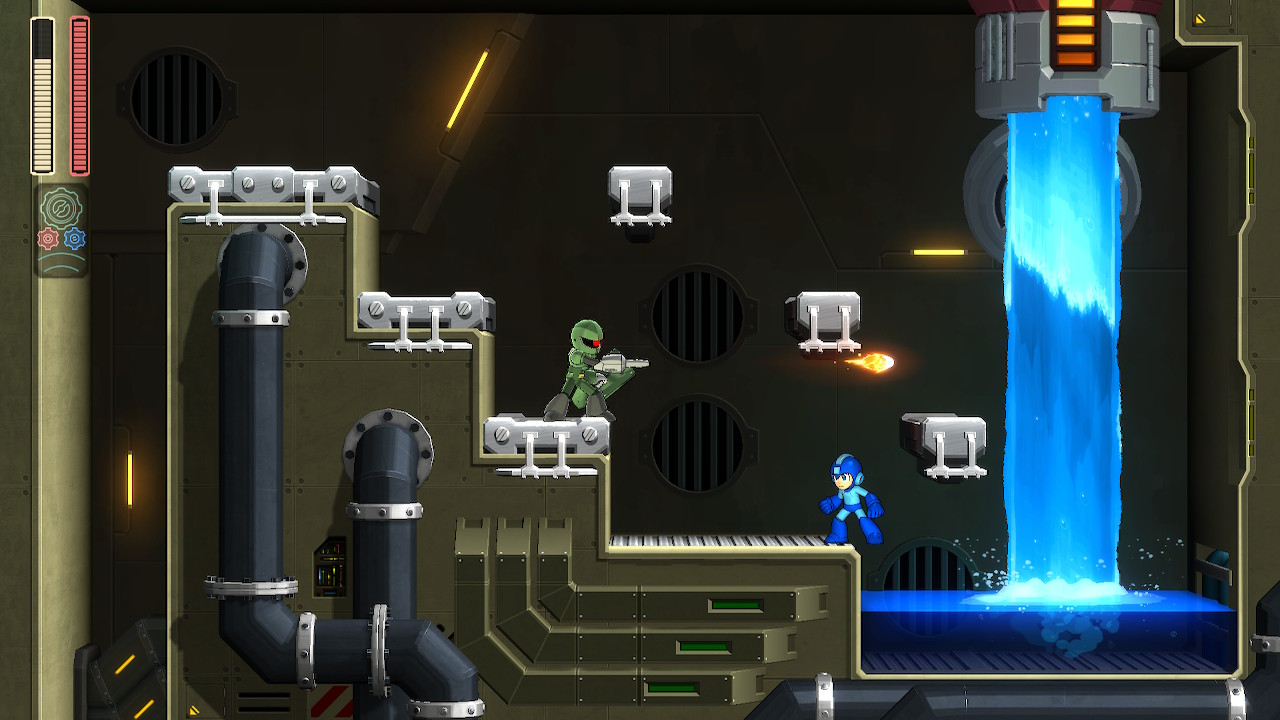

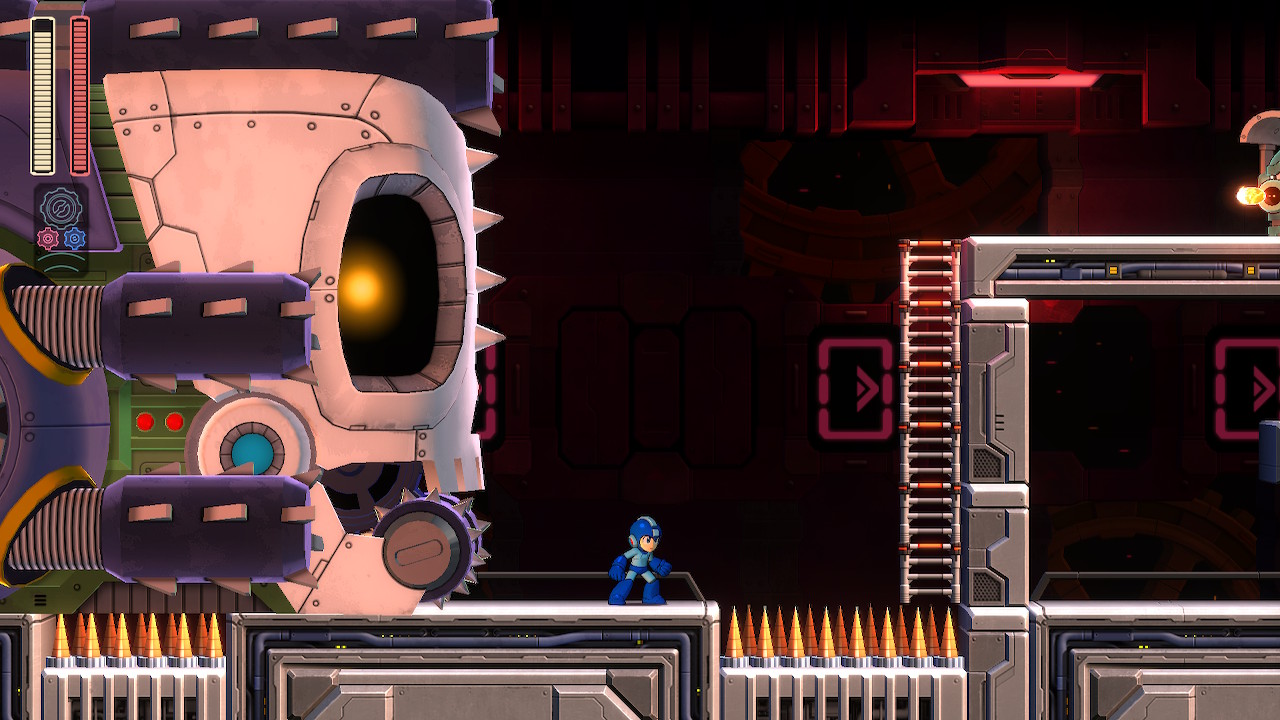

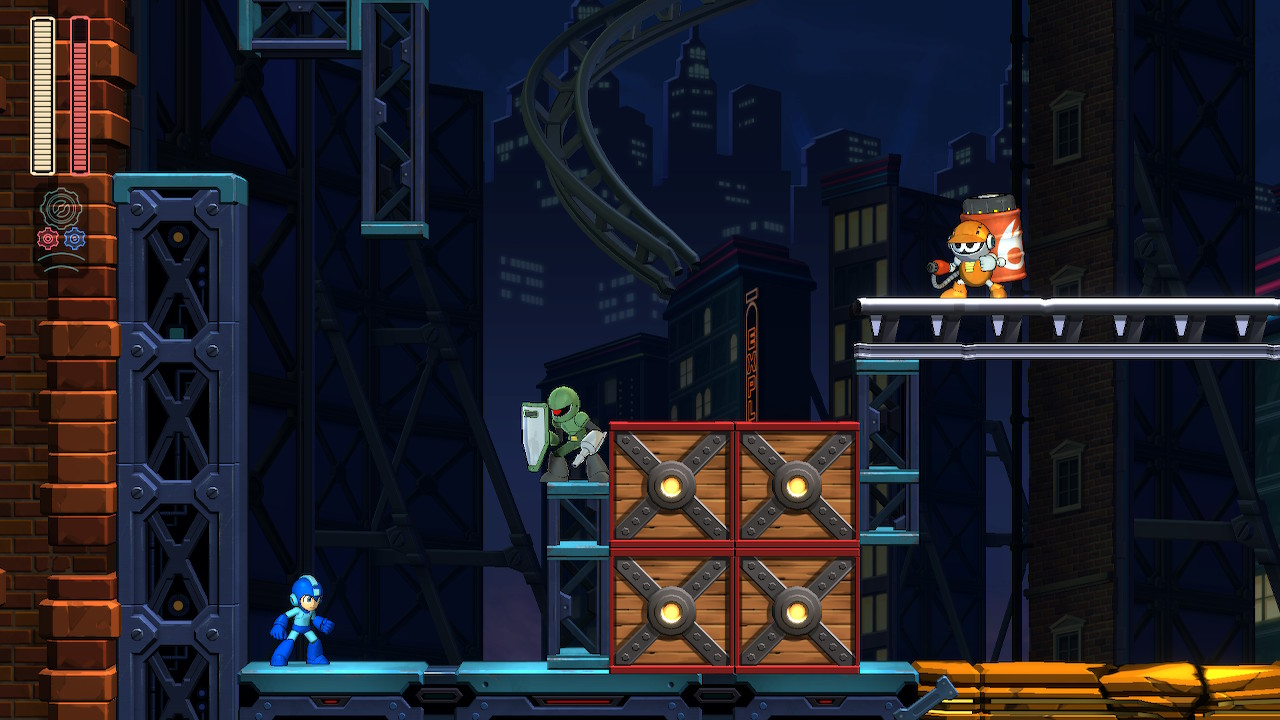

Now that I’ve namedropped some of the Robot Masters, I guess we might as well look at the stages. They run the gamut, to be fair. There’s good stuff in there. The problem is that most of it is as bland as a Mega Man stage can possibly be.

The absolute blandest stage is probably Block Man’s, which is so non-descript that the level elements all feel like placeholders. Being as he’s called Block Man, I suppose the fact that his stage is just full of…blocks is fine, but there feels like there’s no love here. It feels at best like a concept nobody bothered to execute, and there’s no real gimmick unless you count the fact that blocks fall from the ceiling sometimes. I’m not suggesting that every stage needs a gimmick — gimmicks in these games can be pretty awful — but it needs something, and it instead has nothing.

Weirdly, this is the stage that was used as a demo for the game. I remember playing it and wondering why they chose something so completely unmemorable as the demo, ultimately concluding that they must have wanted to save the more surprising levels for the game itself. Fair enough, but I was wrong. Block Man’s stage is exactly as surprising as Mega Man 11 is on the whole: not even a little.

You do some light platforming. You shoot some enemies. You move to the next room and do it again. Sure, that’s technically Mega Man, I guess, but doesn’t this stuff usually feel…fun?

Of course, I now know why they chose Block Man’s stage: They wanted to trick us. Block Man’s boss fight is the one time that the Double Gear System seems like it might make an actual difference to the way the game is played. Other Robot Masters just activate their Gear and either move more quickly or hit harder. Block Man, by contrast, transforms.

Block Man is the only boss in the entire game to get another phase that consists of more than a new attack or two. He starts as one boss, becomes a second boss, and then reverts back to his original form with new behavior. It’s interesting. I won’t say that it’s good, but somebody invested some care into here the idea.

The other bosses, though? Nothing. Capcom gave us Block Man in the demo so that we’d be tricked into thinking that this was how Robot Master fights in Mega Man 11 would go. They gave us an outlier so that we’d assume it was the baseline and pull out our credit cards. Joke’s on you, Capcom; I buy whatever crap you make anyway!

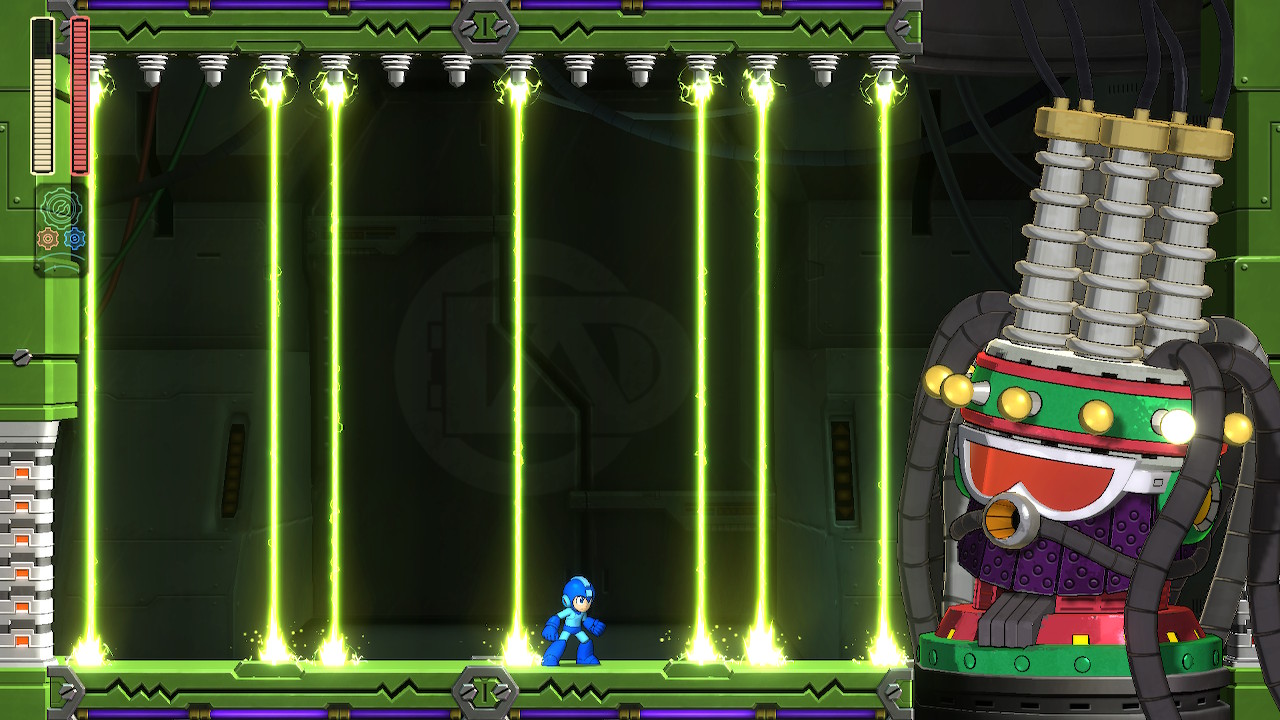

Fuse Man’s stage is nearly as bland. There are a few platforming sequences that require some degree of timing, but really it’s about as basic as an electricity-themed stage can get. You usually get a good view of what the hazards involve so very little of it seems unfair, but none of it feels creative. Except for the miniboss, I guess. I don’t know what miniboss I would have expected here, but a Rasta-man dynamo wasn’t it. Technically that makes it creative, I think?

Speaking of minibosses, every stage has at least one, and I never realized what a pace breaker that can be until Mega Man 11 drilled it into me. They’re rarely difficult, but they certainly get tedious fast. Other games use them sparingly, which is both a good idea in general and helps the stages in which they do appear to stand out a bit. In this game, they’re everywhere, making them feel less special and more like a chore.

It doesn’t help that few of them feel…right. Bounce Man’s stage has an inflatable frog piloted by a little robot who reinflates it each time you puncture it. That’s cute. Tundra Man’s stage, though, just has a woolly mammoth skeleton on a plate. Who gives a shit? Block Man has a stack of discs, just to ensure that everything about his stage is the least interesting thing imaginable. Impact Man has a guy in a shovel mech. Acid Man has some kind of toilet scrubber. Torch Man has a screaming chicken. How many of these sound like the creations of people who loved what they were doing?

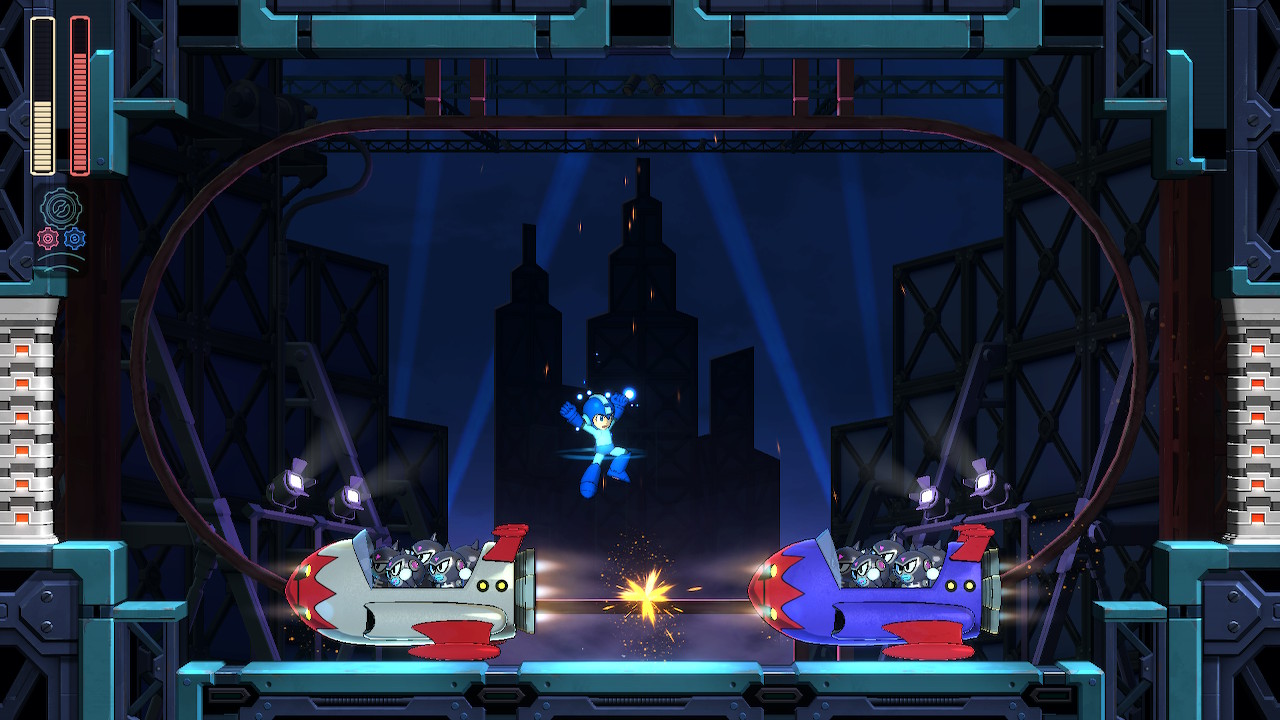

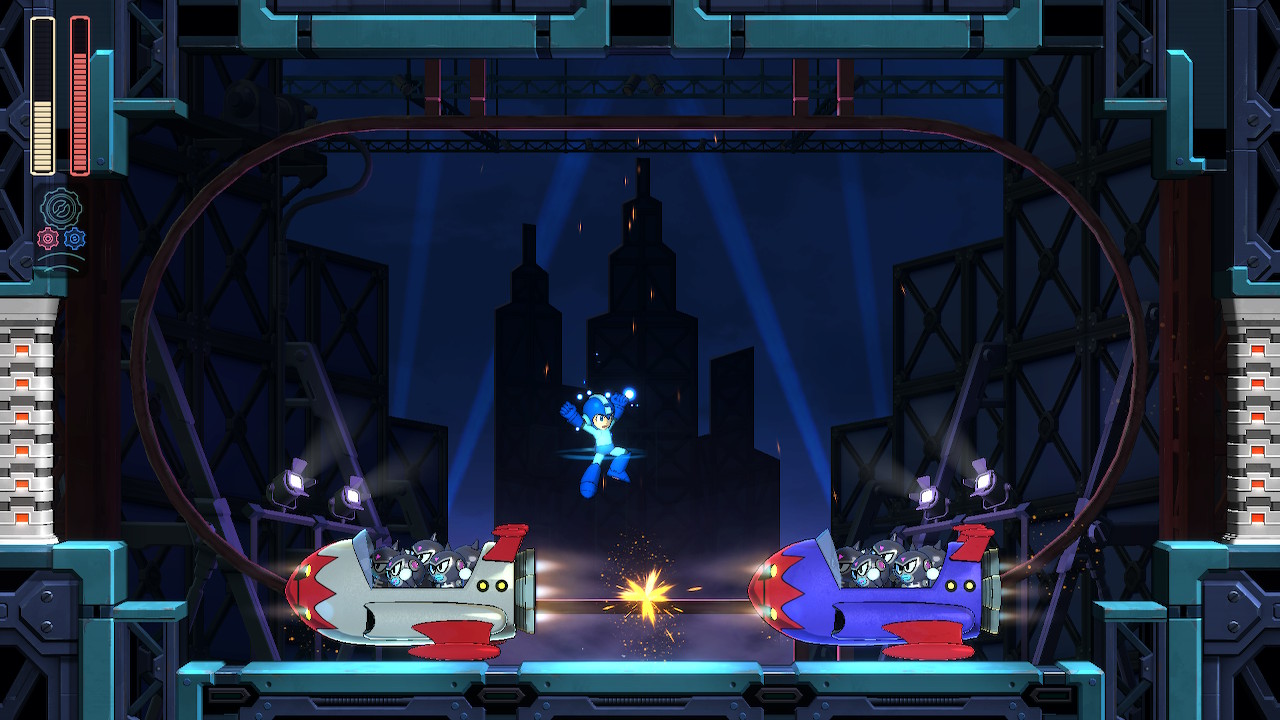

The best of the minibosses, without question, is the one in Blast Man’s stage, which involves hopping around two roller coaster carts loaded with explosive enemies.

You need to avoid the vehicles and shoot the enemies so that they collide with the coasters and deal damage. It’s actually pretty great, requiring forethought and solid reflexes. I like that one a lot, and it makes me realize how much more I’d enjoy the game if we got fewer minibosses, so that each of them could each have had more attention paid to their design. I’d rather have three or four good ones than eight basic ones that just require me to hop over bullets and shoot them until they keel over.

Next is probably Impact Man’s stage, which isn’t much better but at least tries some new things. At various points in the stage, Impact Man’s limbs will fly around and make it difficult for you to navigate certain rooms without taking damage. It sucks, but it’s also kind of interesting, I suppose. I mean, I hate it, but it’s something.

In the grand tradition of ground-based Robot Masters, Impact Man’s stage is a bore. No pun intended. Unless you liked it; in that case, I intended it.

Then there’s Bounce Man’s stage, which is at least colorful, marking a massive leap forward. It’s still not great, though, and something about the whole thing felt unintuitive to me. For instance, it took me ages to figure out how to ascend the long vertical passages lined with bounce balls. Am I moron? Probably, but I was a frustrated moron until I figured out that I just need to leap into them and hold down the jump button. That’s it.

Should I have figured that out more quickly? Maybe, but I’m still not sure what there was to figure out. Holding jump on a row of horizontal balls bounces me higher vertically, which makes sense. I could therefore intuit that holding jump on a row of vertical balls would bounce me farther horizontally…but, no, it actually moves me vertically again.

How was I supposed to guess that? What’s the logic behind that working? And now that I have figured that out, am I supposed to enjoy it? Does holding the jump button for a few seconds while the game does all the work count as gameplay?

I’m still not sure how the slap-hand boxes work. If you shoot a hand, it flops over. If you’re standing on the platform after a few seconds, the hand returns to its upright position and slaps you off. That’s fine, but sometimes it slaps me across large gaps, which seems to be intended, and other times it slaps me right into the same gaps, and I can’t figure out why the outcomes are so different when I approach the situation the same way.

At the very least, the main soundtrack here sounds like it’s trying to be playful. It’s still not great, but it’s a nice break from the cascading electronic wheeze that we hear throughout the other stages. (Seriously, listen to the Wily Numbers versions instead. It’s actual music, and you’ll be surprised how rich it sounds in comparison.)

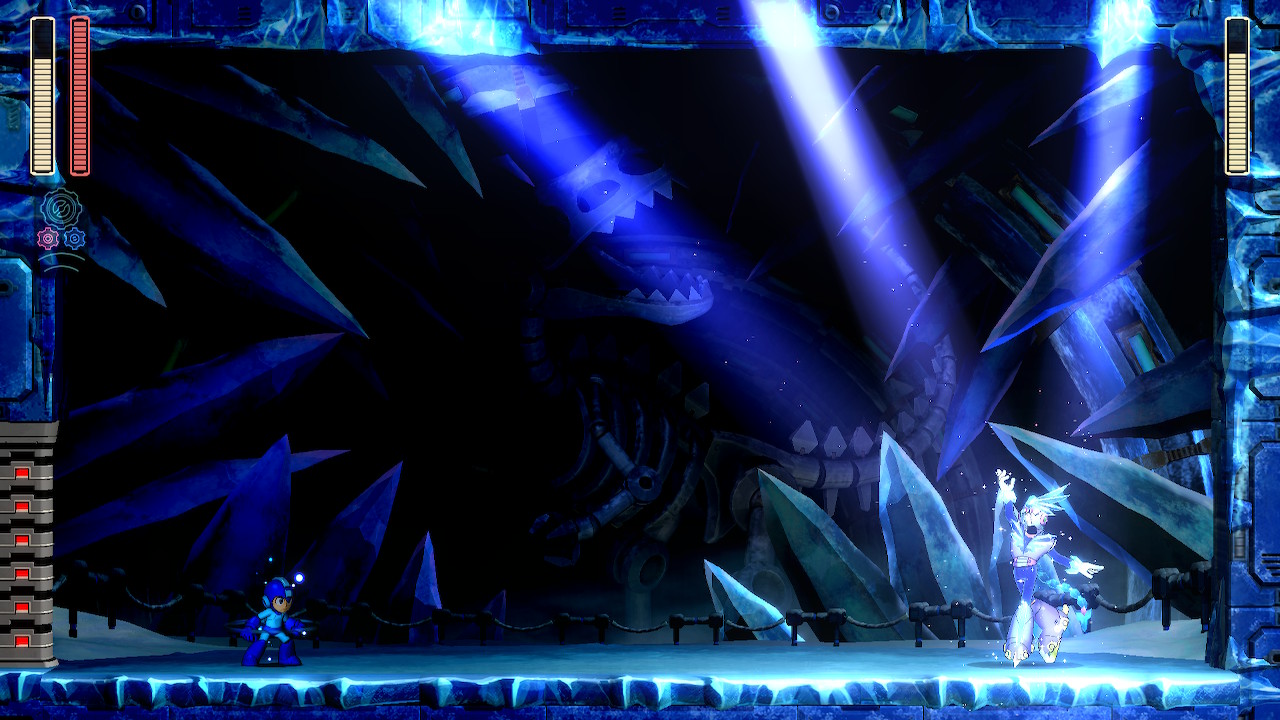

Tundra Man’s stage is a bit better, I suppose. It’s still largely dull, though, and it ends with an annoying series of jumps through narrow passages during a wind storm, which is not a great way to conclude things. Also, the stage keeps giving us tight corridors during enemy encounters which, yes, does make them difficult, but also doesn’t quite qualify as creative design.

On the bright side, the Wily Numbers version of this stage’s theme is fucking fantastic. (Have I mentioned how much I enjoy the Wily Numbers songs?) I always save this level until last for that reason alone; it’s a very high note to end on.

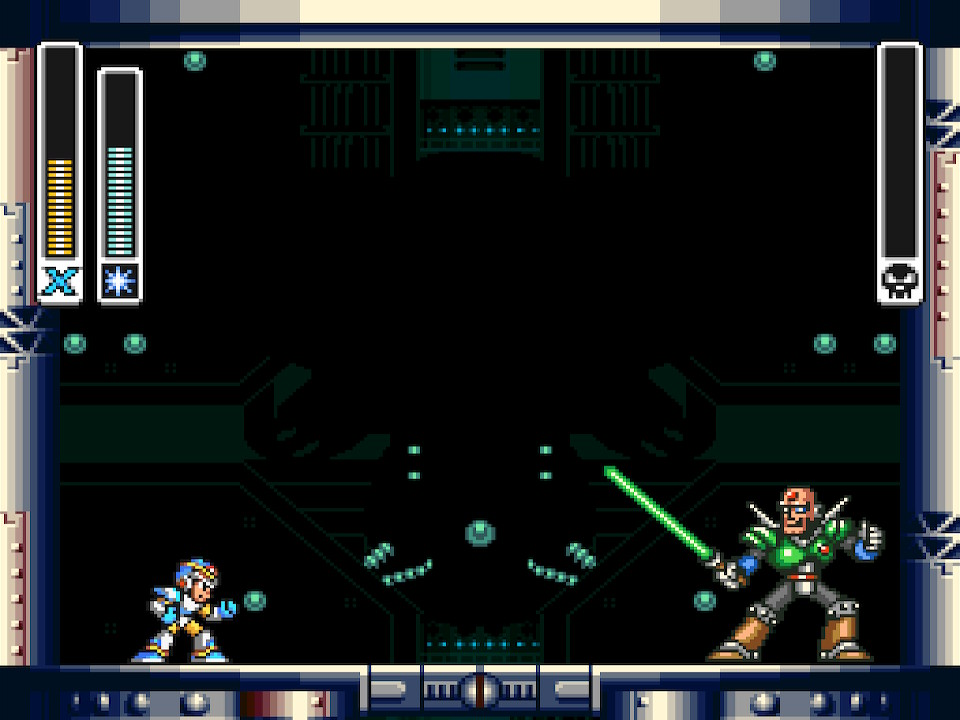

The Tundra Man fight itself is the best in the game. He’s a memorable Robot Master with a strong personality, unlike…whoever most of the others are meant to be. Tundra Man is an ice dancer, announcing his moves as he goes and encouraging us to dance along. Sure, he’ll kill us and do so with pleasure, but he wants us to participate. Learn his moves, react in kind, and the fight gets easier, sure, but it also gets immensely satisfying. He reminds me, in a way, of Sword Man from Mega Man 8. That fight played like a duel, and this one plays like a duet. It’s lovely stuff, and it really does elevate the entire level.

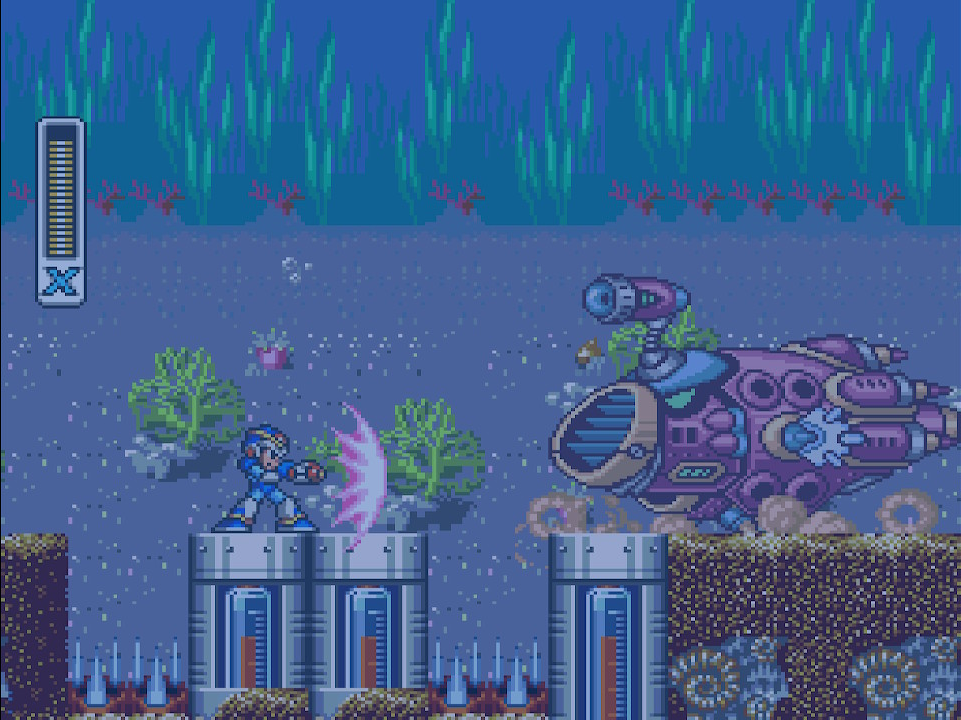

Moving into the better levels overall, we have Acid Man’s stage, which isn’t great but it has a lot going for it. I like that this game’s water stage isn’t full of water, but rather a substance that is far more dangerous. The acid doesn’t actually damage us during the submerged sections, but just knowing that it is acid keeps us on our toes and prepares us for how dangerous things are.

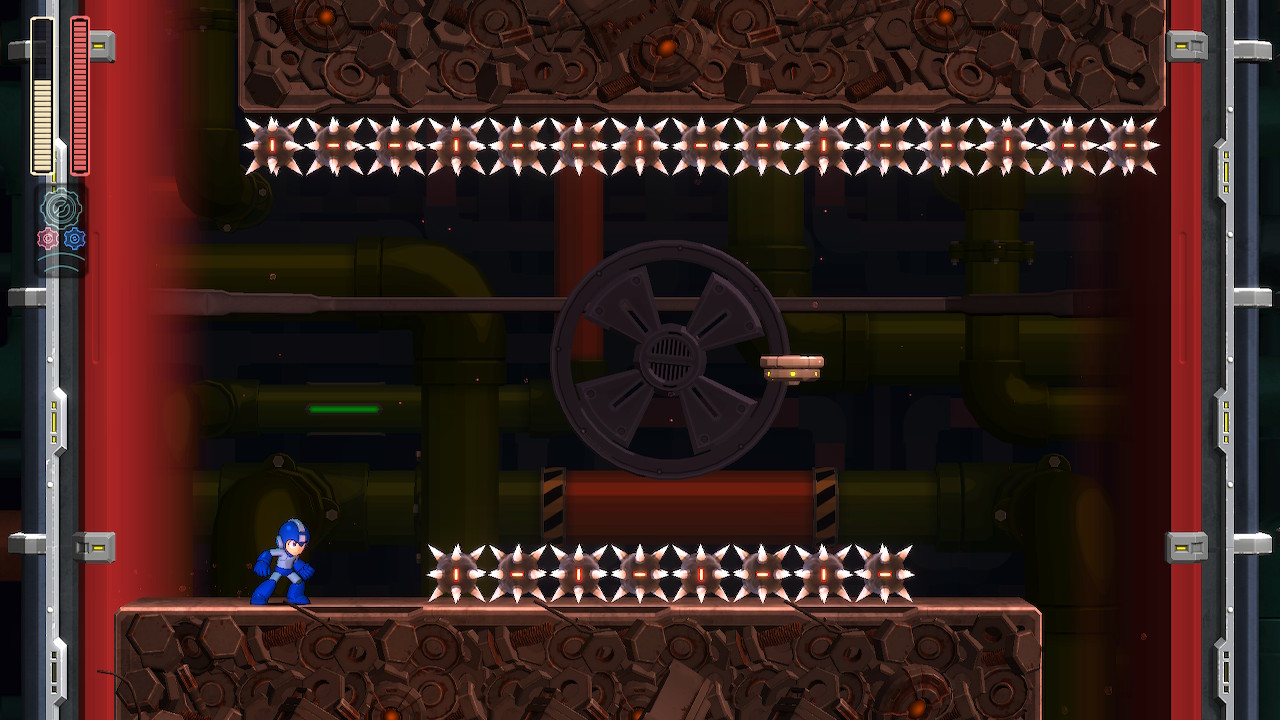

Sadly, there’s a huge reliance on death spikes in conjunction with tricky (and varying) water physics, as well as narrow, moving platforms that will carry us right into the spikes if we aren’t careful. As such, I tend to remember this level as being one that drains my lives a bit too quickly to feel fun.

It’s doable, and it’s not unfair, but it’s also not fun enough to justify the irritation, especially when you just barely clip a death spike near the end of the stage and get rocketed all the way back to the checkpoint, forced to navigate mazes of instant death traps all over again.

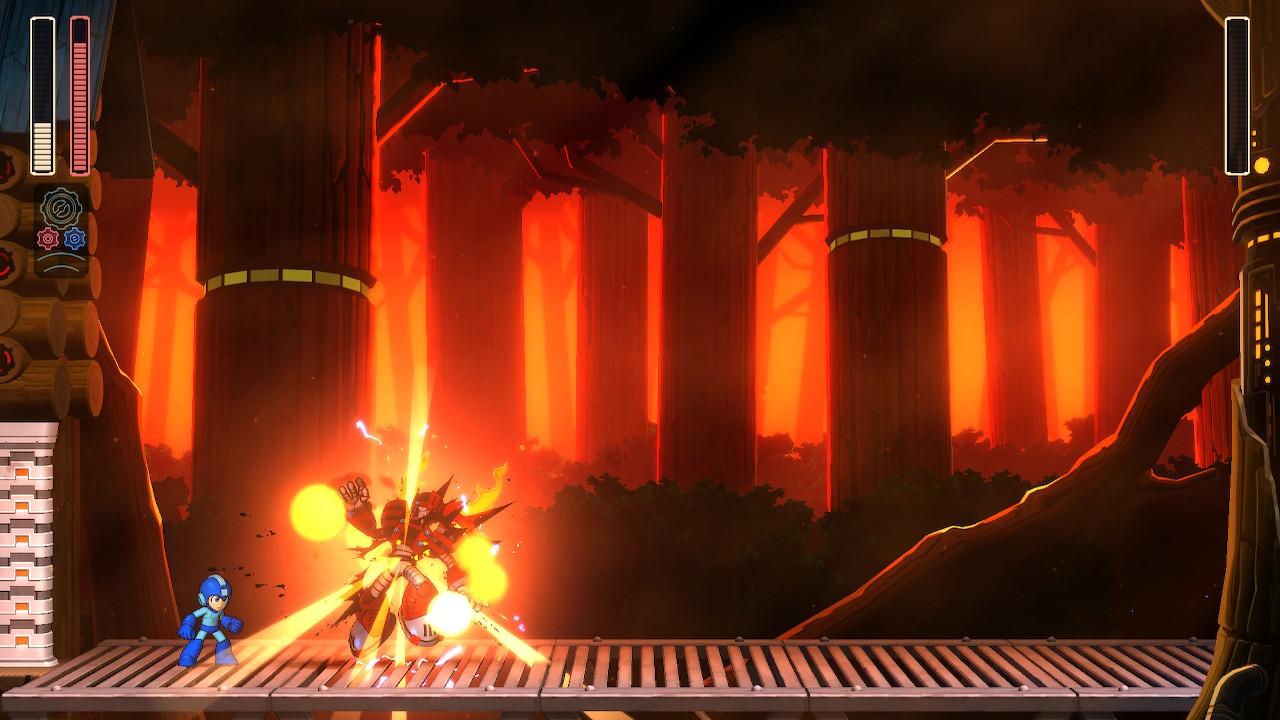

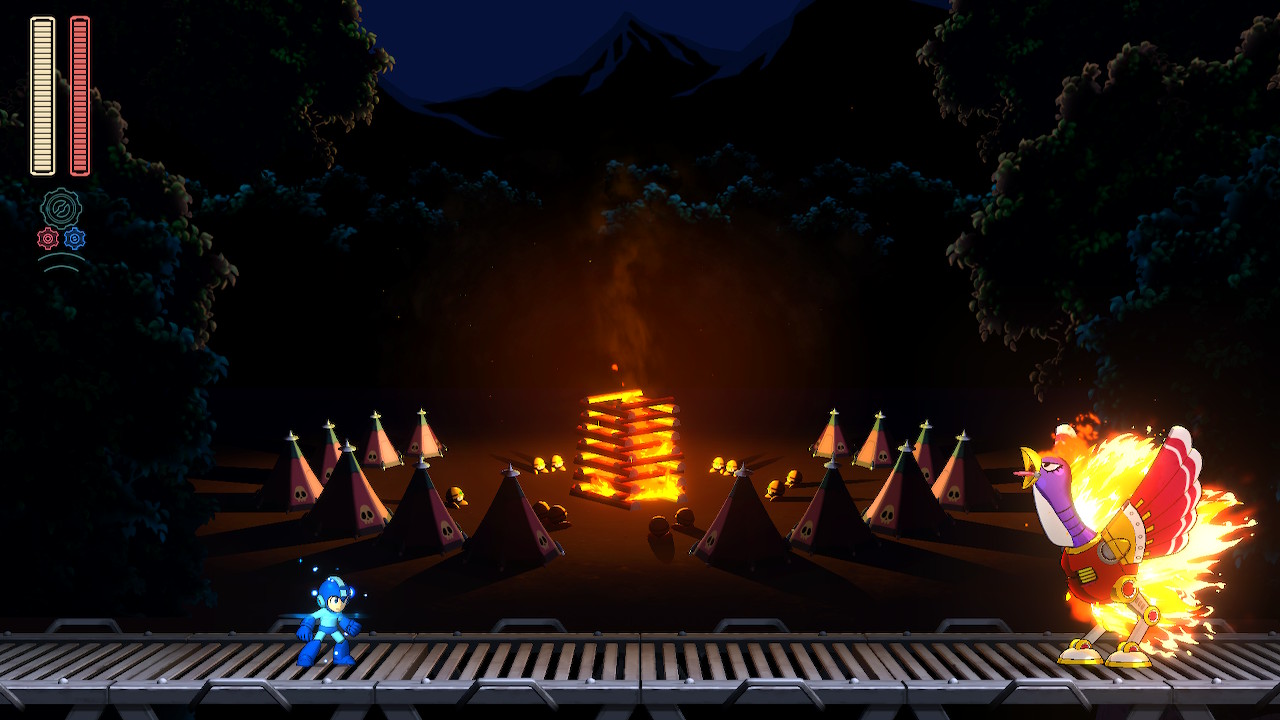

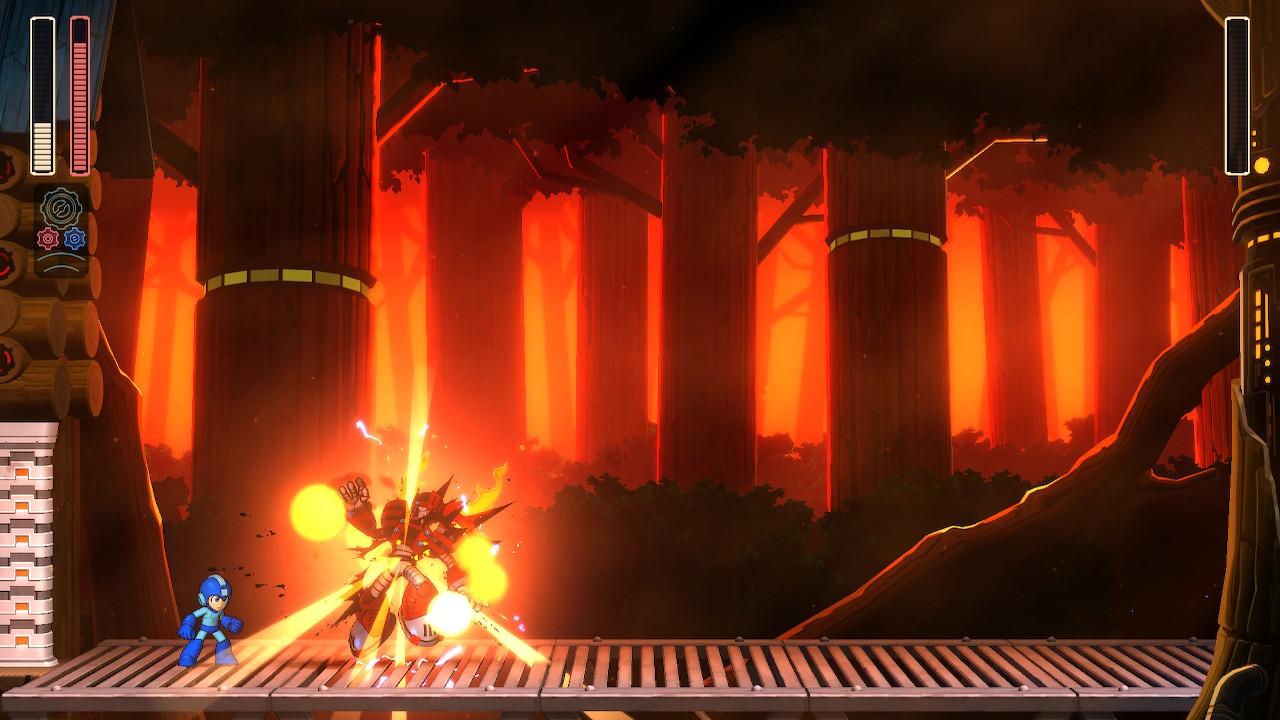

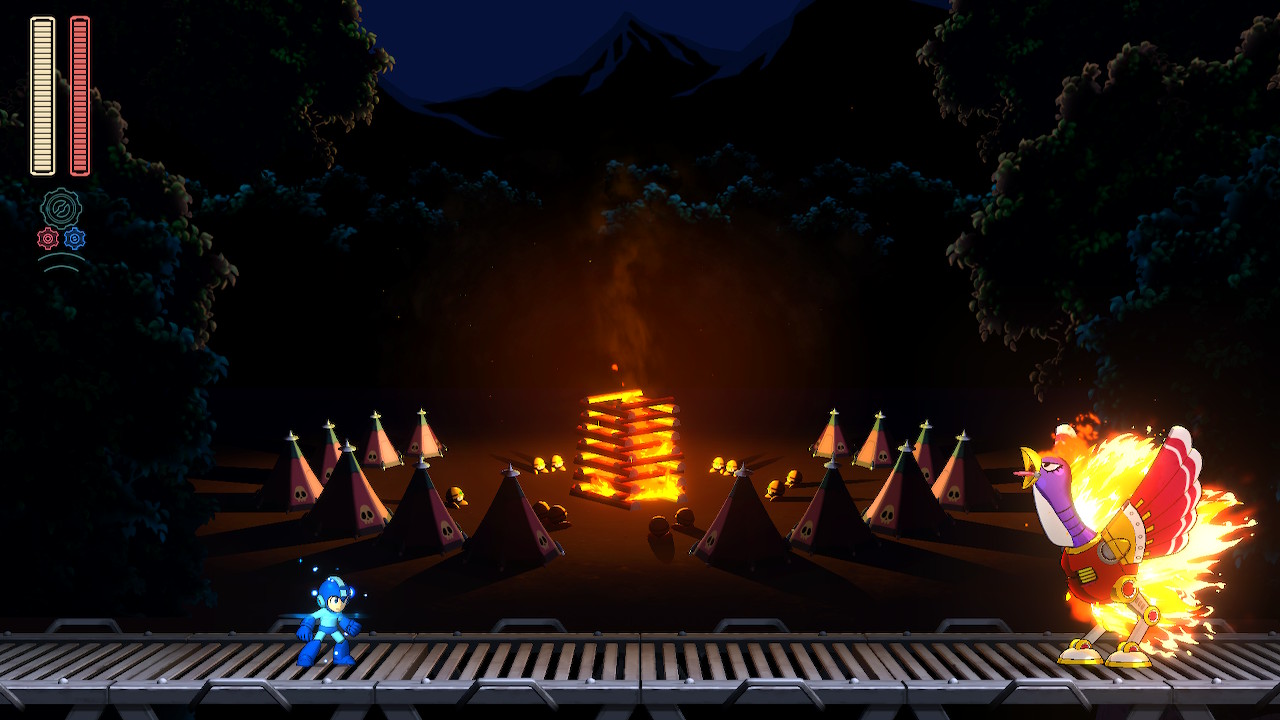

Torch Man’s stage is, in some ways, my favorite. It has an absolutely wonderful campout aesthetic, which is a unique idea well executed. That comes with all of the expected superficial visuals, sure, but it also means that the stage takes place at night, requiring you to keep a source of light around — usually in the form of an enemy — in order to see where you’re going.

There’s a lot of creativity on display here. The lantern owls, the kettle critters, the sentient camp stoves you can turn off briefly to use as platforms…it’s good stuff, almost throughout.

Almost.

Then we have the forest fire segments, which are great ideas, but not enjoyable in the slightest. These sections give the Speed Gear a chance to shine, as you’re chased by a wall of fire that kills you on contact, but the window to react is far too narrow. You’re forced through tight passages and required to hop quickly between small platforms, usually while besieged by bullet-sponge enemies that hem you in, and it’s simply not fun.

It is bad enough when one of Acid Man’s spikes sends you back to a checkpoint, but that usually comes down to carelessness that was reasonably within your control. Here, the fact that you didn’t flawlessly execute a pixel-perfect hop through a winding corridor at the end of an overlong chase sequence just makes the stage feel unnecessarily arduous.

Add to this the fact that Torch Man himself moves quickly and — for the first few attempts, at least — unpredictably, and you’ll end up having to replay the stage many times. Plodding through these long forest fire sequences, hoping they don’t rob you of your lives before you even get to try fighting the boss again, seems sometimes like you’re being punished by the developers rather than tested by them.

It’s doable, certainly. I can do it. But I can do everything that Mega Man games have asked me to do. I don’t think that that inherently means that everything they ask us to do is equally fair.

Then, finally, we get to the lone stage that I’d truly call good: Blast Man’s.

This stage is just wonderful. Like Torch Man’s, it has a fantastic concept, here being an explosion-based attraction at an amusement park. This could have been (and should have been, in all honesty) explored further. There should have been more in the way of silly advertisements and attractions and whimsy, instead of the standard crates-and-girders layout we get here, but it’s something.

The concept is executed just well enough that I can still appreciate it, in spite of the fact that I wish it went far beyond this. Exploring a deadly carnival attraction is wonderful, as is the fact that the little explosive robots in this level aren’t just enemies; you can use them to solve basic puzzles and even defeat larger enemies. It’s kind of adorable and often a lot of fun.

The best part is that it takes the forest fire segments from Torch Man and does them right. Many times in Blast Man’s stage, you’ll have to navigate a series of exploding platforms. Here, however, they are shorter, and you can usually see most of what you’re up against before you trigger the explosions. There’s little on-the-fly guesswork; you have a chance to see what you’ll need to do before you need to do it. That doesn’t make anything easy, but it makes it far more sporting, which itself ties into the amusement park nature of the entire stage.

Basically, Blast Man does the same thing, but more often, better, and in shorter bursts. It’s as close to perfect as this game ever gets, it leaves the rest of the stages in the dust, and it ends with one of the best boss fights as well, second only to Tundra Man. Whoever designed this stage deserves a round of applause; this is definitely the pick of the litter.

Speaking of litter, the Wily stages in this game are absolute garbage.

There is nothing creative or interesting about them at all, and there are only two. Okay, technically there are four, but one is just a small room before the Robot Master refights, and the other is a small room before the Dr. Wily fight. That’s it. The game can’t wait to get this over with, as though the developers couldn’t even feign enthusiasm anymore.

Wily stages are typically weaker than the main stages in any Mega Man game. I get that. But no other game in the entire series has ever thrown up its hands so quickly and clearly. The others at least tried. They attempted to leave us with some kind of spectacle, or insane difficulty, or some weird, memorable gimmick.

Here, we get nothing.

The first Wily stage has some gears we have to jump on. Some fall apart. You fight the Yellow Devil’s third cousin at the end. That’s it.

The second Wily stage has a big robot that chases you through some rooms. You fight a face in an egg at the end. That’s it.

That’s the entire Wily fortress. It’s a complete waste. Wily stages may often fail, but this one doesn’t even try. It’s an absolute joke and it feels insulting to come this far and be rewarded with the developers saying, “We didn’t bother making the rest of this game.”

I can’t even talk much about the Robot Master weapons, because none of them are very good. Block Dropper drops blocks. Blazing Torch launches a fireball. Scramble Thunder sends out an electric spark that crawls across the floor, because we didn’t already have enough special weapons that did exactly that already.

A couple of them are fine, but probably accidentally. Acid Barrier is extremely handy, as you get a shield and a powerful projectile at once. Pile Driver is a great idea — it’s effectively an air dash with high collision damage — but there’s rarely a reason to use it. It makes mincemeat out of the second Wily stage, though, if you ever want to leave that behind as quickly as possible. That’s it. There’s no room for discussion, because the game feels almost calculated to not give us anything to discuss.

So that’s what Mega Man 11 is. A few glimmers of greatness, a whole lot of blandness, and an entire ending sequence it can’t even pretend to care about. That, I suppose, answers that question.

But what about the other question? What makes Mega Man Mega Man? What’s missing here that prevents it from feeling like a Mega Man game? Or maybe the better way to ask the same question is this: What’s preventing me from feeling the same way about it as I do the other Mega Man games?

Well, let’s go back to jumping through the boss gates.

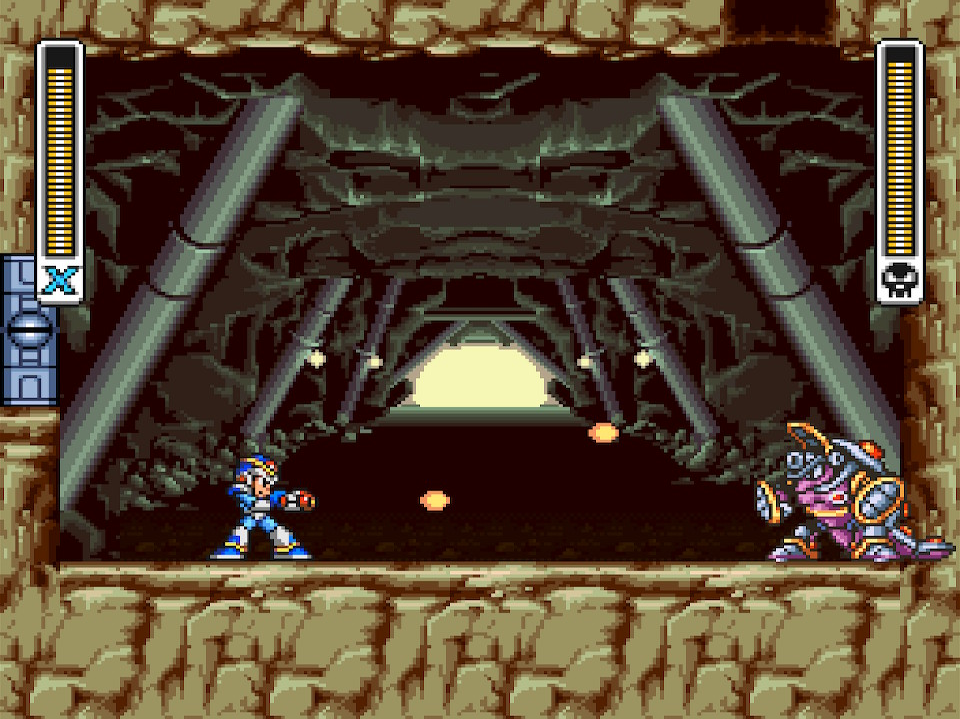

See, I didn’t just bring that up, make a point, and move on, like a sane human being. I figured I’d go back to the previous games — each of them — and make sure that my memory weren’t playing tricks on me. I wanted to be sure that the boss gates worked that way in all of those games. I wanted to play one level from each and confirm that it was indeed Mega Man 11 that changed things.

And so I did just that. I booted up each of the previous games I covered, and I fought my way through the stages of Cut Man, Metal Man, Magnet Man, Dive Man, Wave Man, Tomahawk Man, Junk Man, Tengu Man, Concrete Man, and Nitro Man. For good measure, I also booted up Mega Man & Bass and did the Cold Man stage. I managed to defeat Magnet Man and Dive Man without taking damage. (On the flip side, Tomahawk Man and Nitro Man kicked my butt.)

I confirmed that, in each case, the boss gates worked the way I remembered them working. I’d jump into them, press fire, and be rewarded with a nice little celebratory sprite hovering through the screen transition, just the way I liked it.

And playing through those stages showed me what the difference really is between Mega Man 11 and those games. The boss gates, sure…but also the process of making it to those gates. The fights that await us on the other side. The final stages we unlock after surviving all of those encounters. The new weapons that we earn and get to play with.

Replaying those stages helped me see just how little personality Mega Man 11 has.

The previous games, primitive as most of them are, are positively bursting with personality. Everything has love behind it. I may not always reciprocate that love, but I feel it. I see it. I know it’s there. There’s evidence of it on every screen. People made those games because they cared about what they were doing, and they wanted to give us the best Mega Man experience possible.

The results were often messy, but they were more often thrilling, satisfying, exciting, and unforgettable. Even the failures were interesting.

In Mega Man 11, though, I don’t feel that. Any given stage from the previous games has more personality than the entirety of Mega Man 11. Everything here feels — and looks, and sounds — so flat. Everything fulfills the barest, most superficial minimum we’d expect from a Mega Man game, and then goes no further. It’s always true to the letter of the law and never true to the spirit.

So we get a new set of Robot Masters. We get themed stages and weapons. We get electronic music. We get enemies with big, goofy eyeballs. We get to beat up Dr. Wily again. And when we’ve done all of that, the game ends and we get to go home.

The difference is that we never wanted to go home before. We wanted to enjoy our time in these games. We wanted to savor it. We wanted to replay them over and over again, finding new ways to navigate tricky rooms and new paths through the games with different sets of weapons and utilities. We wanted to immerse ourselves in these little worlds, dangerous though they were, because there was so much love inside of them that we were willing to overlook everything they did wrong.

Mega Man 11 closes the door after us and turns off the lights, because once we’ve finished playing it, there’s no real reason to stick around. It doesn’t seem to want us sticking around anyway. It fulfills its duty of being a Mega Man game and no more. Ironically, that makes it feel like it’s not a Mega Man game, because we’re not used to Mega Man games feeling so…artificial.

When the personality does come through, it is very welcome. The Tundra Man fight has personality. The Torch Man stage concept has personality. Blast Man’s level design and miniboss have personality. And the Wily Numbers soundtrack, of course, has personality. The real reason those songs work so well is that you can hear the human beings behind the compositions. You know people are there making the music, having fun, caring about what they do. That makes a difference.

In the rest of Mega Man 11, there’s no sense of the people behind any of it. There’s no feeling of love, of personality, of warmth, of care. It’s not a world. It’s just a picture painted on a wall.

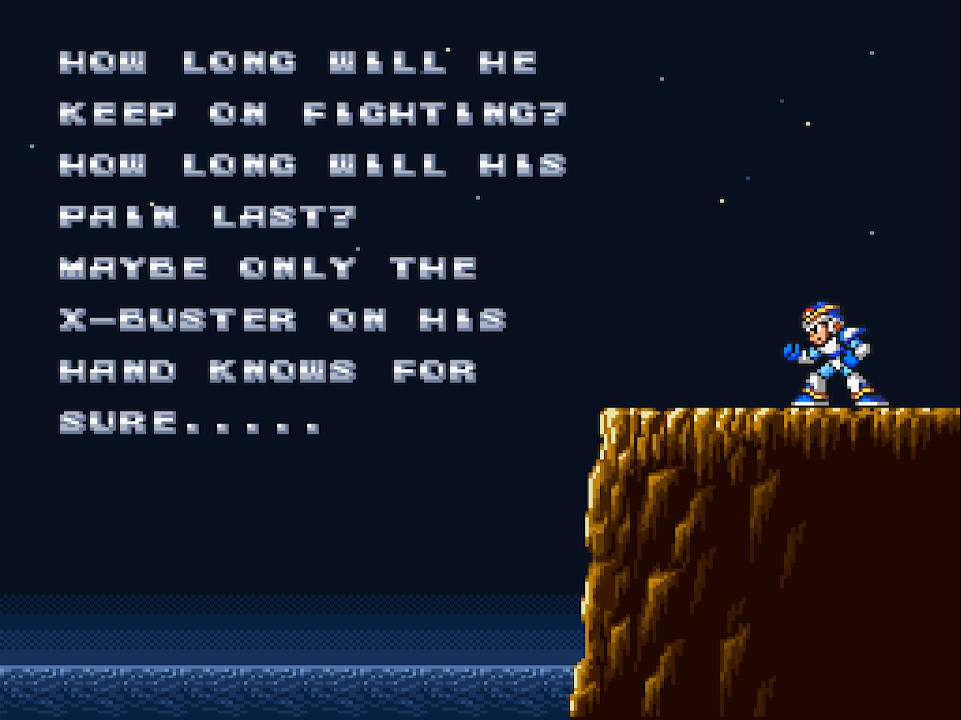

That’s what makes Mega Man Mega Man: personality. It bled through in small ways in the past, such as by letting you posture confidently while moving through the boss gates, and those small ways added up. They defined the Mega Man experience beyond the Robot Masters and special weapons and weaknesses and stage themes and everything else that seems like it should matter but really doesn’t.

Mega Man 11 has everything that doesn’t matter, and nothing that does.

That’s the difference.

This is a Mega Man game, certainly. We can’t rightly argue that it’s not. But it’s the absolute least anyone could have expected from one, feeling more than ever like it came from a sense of obligation rather than invention.

There will be a Mega Man 12 at some point. I just hope Capcom actually wants to make it.

Best Robot Master: Tundra Man

Best Stage: Blast Man

Best Weapon: Acid Barrier

Best Theme: Bounce Man (unless you allow the Wily Numbers tracks, in which case it’s Tundra Man)

Overall Ranking: 2 > 9 > 7 > 5 > 4 > 10 > 3 > 1 > 6 > 11 > 8