Here’s something some of you don’t know about me: a few years ago, I finished a novel. It was called Afterbirth: The Comedy of Miscarriage, and it was around seven years in the making. That was a long time to spend with one project, and, as you might expect, I was substantially invested in it. I still am.

It was — and I guess is — the autobiography of a sperm. Our single-celled hero narrates the circumstances around him, the generations of couplings and false-starts and abandonments that culminate in his fertilizing off an egg…and eventual miscarriage. Needless to say he’s rather bitter, and much of the fun of writing this book had to do with the narrative perspective. What would have been, on its own, a story of a young man who does something foolish with a younger girl, suddenly became this massive, epic sprawl…simply because that moment, that night, that one bad decision — and the bad decisions that led up to it, and the bad decisions that followed from it — formed, for this narrator, his entire experience of life. The smallest thing was now the only thing. Everything was reconfigured and filtered through a unique and cynical perspective.

It was literary, it was jarring, it was dark. It was also unmarketable.

Because here’s something you do know about me: I’m a nobody.

Getting agents and publishers interested in this deliberately shifty, chronological scramble of loss and dissolution — hinging (though not explicitly so) on an act of statutory rape — was a tough sell. If I had a name…a name that people recognized…a name that people cared about or wanted to care about…it would have been another story. At least potentially. As it stood, it wasn’t the kind of gamble any agent or publisher in their right mind would have made.

I believe in the book. I’ve spent enough time with it and gotten enough glowing feedback on it that I know it’s very good, and that a certain type of reader would absolutely love it. But I don’t begrude anyone for not wanting to publish it. Why would they?

So I decided about three years ago on a course of action: I would write something that was marketable.

Why? So that I could market it. And hopefully get it published. And even more helpfully develop myself as a name people recognized, cared about, or wanted to care about. I’m not surprised at all that a literary mindscrew by a literal nobody faced nothing but rejection. But what if that literary mindscrew had some pedigree behind it?

I decided to write a pastiche of the detective fiction genre. This wasn’t for any particular reason except that “pastiche of the detective fiction genre,” as vague as that description is, still lights up some very clear expectations. It’s more marketable simply because there’s so much I don’t have to market. You hear that description and you immediately know the kinds of things to expect. You may not know the particular melody, but you sure as hell know the key it’ll be played in. And you, phantom agent, phantom publisher, will know from that alone whether it’s something that would interest you at all.

I felt a little cheap when I started writing it, because I wasn’t writing from the heart. I was writing something to sell…I wasn’t writing to express myself. I was writing something good, or at least I hoped I was, but it was a very different feeling from Afterbirth, which came from the heart in all kinds of ways. Afterbirth was born of my love of deep and confounding literature, of my darkest social and romantic and emotional fears, of my fascination with fate and circularity and patterning. Detective Fiction was born of my desire to be a published author. It was a very different thing.

And so I wrote, and I read. I researched the genre enough — just enough — to become familiar with how this type of story had to work. I read James M. Cain. I read Dashiell Hammet. I read Raymond Chandler. And I was amazed at just how good these books were. As much as we look back on hard-boiled detective fiction as a sort of ropey escapism, there’s actually a good amount of poetry in there…particularly in the case of Chandler, whose conflicted love for his own hero Philip Marlowe bleeds through the characterization in such unexpected and beautiful ways. I was impressed…but I was just writing a parody. I didn’t want that. I didn’t want it to get too good…that’s what ruined Afterbirth.

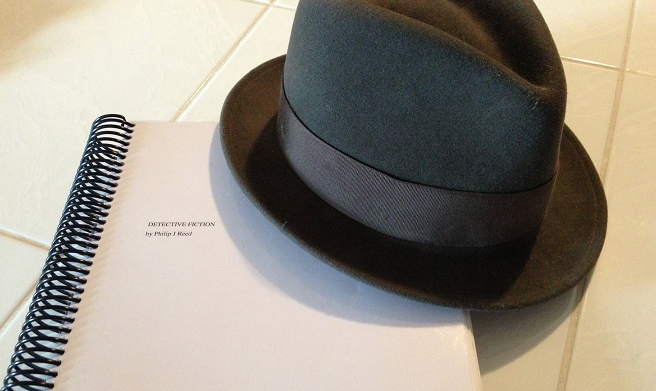

Detective Fiction was the story of Billy Passwater, who in the summer of his 29th year decides to become a private detective. Billy has no certification, no training, and no desire to take any of this seriously. But he has a pretty sweet fedora, and that’s a good enough start.

It was fun to write that much. I set it in south Florida, because I was familiar with the area and I thought the overtly tourist-friendly facade would make for a nice contrast to the noir-inspired elements of the book. It was a fun and immediate contrast that, I think, ended up informing the book in lots of ways I didn’t expect.

But at about the halfway point, something happened. A chapter more or less wrote itself without me. I had slid the pieces into place — as the author I kind of had to, but beyond that I can’t take any conscious credit — and the next thing I knew, we were off in a whole other direction. This happened at what is now the midpoint of the book…central in so many senses of that word.

And that’s when I realized who Billy was. Or, rather, when he showed me who he was. That, yes, he may have started as a sort of blank character I could force through the meat-grinder of familiar tropes and hallmarks so that we could all have a good laugh…but once I saw who he was I had an entirely different book on my hands, and most of the time I’ve spent writing Detective Fiction has been re-writing Detective Fiction. Because from that moment on, I knew things about him that I didn’t know before. He was an ugly character. These elements of the genre that I carried over shaped a very different type of hero in this new context. I was writing for a clown…but the moment I saw him without his makeup on, I recognized him as a criminal. It would still be a comedy, but with a different kind of punchline.

Despite my resistance, I had written a good book after all.

What I have now is a 258 page novel that’s still a pastiche of the detective fiction genre. However it’s also the story of delusion, of stubborn refusal, of accountability and passive cruelty and make believe and the refusal to grow up.

And I love it.

And it’s still — dare I speak so soon? — marketable.

It’s in the hands of my trusty group of proofreaders now. They’ll read it and they’ll give me feedback and I’ll take that into account and I’ll give it another rewrite bearing their comments in mind.

And after that I’m going to solicit agents again…and this time I’ll have something of much greater interest to them.

It’s a straight-forward narrative. It’s full of clues and cues and red-herrings. It starts in one place, and ends up somewhere else. It has a single protagonist with a clear objective.

It’s also got blackmail. And comedy. And murder. And sex. And palm trees. And a baseball bat covered in blood and fur. And some more sex. And karaoke.

Oh, and he solves a mystery at some point. Doesn’t he? He tries to anyway. And I sure hope he does, because otherwise I don’t know who will…

It’s something I can sell. And while I’m still ashamed of the fact that that was my primary objective in writing it, creating a great work of straight-forward genre fiction was my objective in re-writing it.

I hope I’ve succeeded. Because I really like it. And I think you will too.

With any luck, you’ll get to read it one day.

Keep your fingers crossed. Even the best manuscript needs a lot of luck.

And after my proofreaders get through with it, I will have the best manuscript.

We can do this.

Congratulations! I hope it goes far.

Both of those sound like something I’d love to read. I only recently watched Season 4 of Venture Bros and the standout episode of that was, for me, “Everybody Comes to Hanks'”, their own take on the “noir” Detective Story. I’ve always enjoyed that type of thing even though I’m terribly uneducated on the genre itself. Case in point, I thought you’d mention le Carré in your list of people who wrote detective fiction before I realised, to my horror, that I was conflating two similar, yet entirely different genrés. My lack of education astounded even me.

–

Seriously, though, I’m sure all of us are keeping our fingers crossed and sending you well wishes and hoping for the best when it comes time to publish both of your stories. And put me down for at least one copy of each when the time come, too.