I’ve often wondered why science and religion have such a difficult time coexisting. I’m not an especially spiritual person, but even when I was a practicing Christian, I didn’t see why the theory of evolution — as just one example — would be seen as such a threat.

Does the existence of a set of rules that govern our universe eliminate the possibility of a God? Why should it? Or, rather, should it have to? Can’t God have created and applied the rules of evolution? I’m not saying He did, or that we need a God to explain anything at all, but having a creator and having demonstrable rules never seemed to me to be mutually exclusive.

I don’t know if John Carpenter agrees with me, but Prince of Darkness certainly does. It’s a spiritual horror film that is also, to exactly the same degree, a scientific horror film. It examines one serious central threat not through two separate lenses, but through two overlapping ones. Not to put too fine a point on it, but Carpenter’s evil in this film isn’t something can be understood by either science or religion. If anyone is to get the full story, they’ll need to understand it through both, at once.

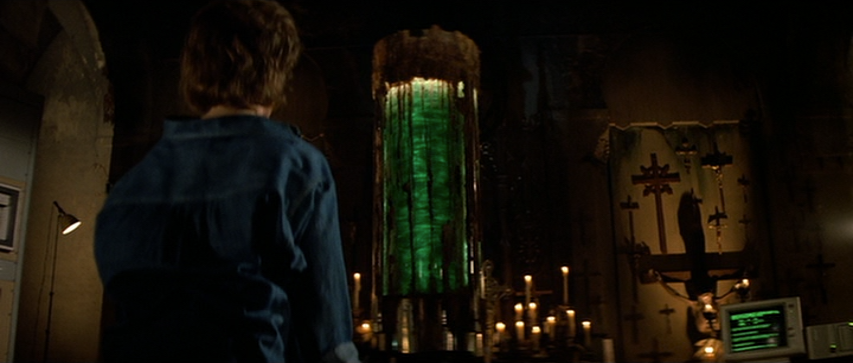

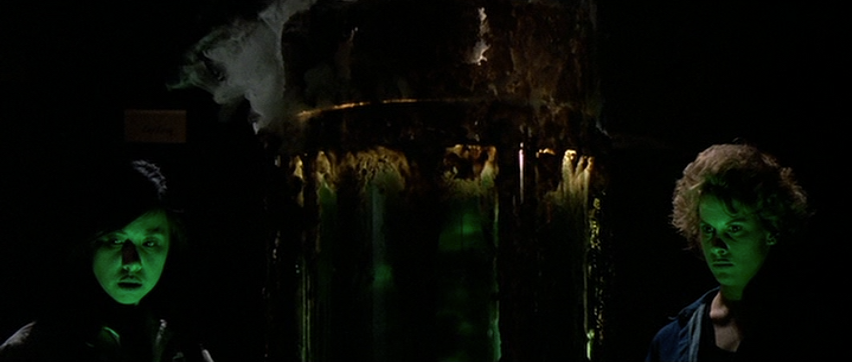

The evil is represented here by a sealed canister of swirling green liquid, locked away beneath a disused church. It’s watched over and monitored daily by a single elderly cleric of The Brotherhood of Sleep, an all-but-extinct order. This lone watchman passes away as the film begins, and nobody is left who understands it.

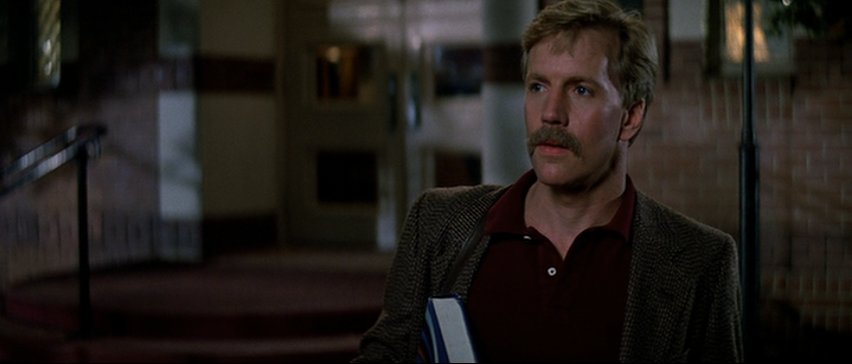

The responsibility falls to an unnamed priest played by the always fantastic Donald Pleasence (Dr. Loomis in Halloween and its sequels, and the president of the United States in Escape from New York), not because he is in any way, shape, or form equipped to handle the problem, but because he’s the only one anyone can think to call. The priest inherits the meager belongings of the cleric: a key to the church basement and a journal containing information that worries him immediately.

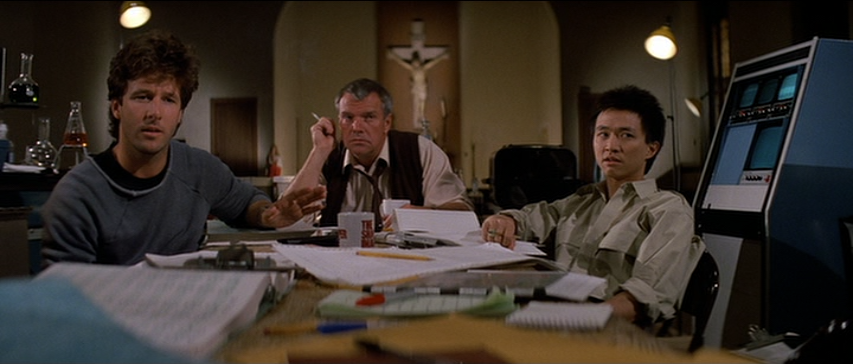

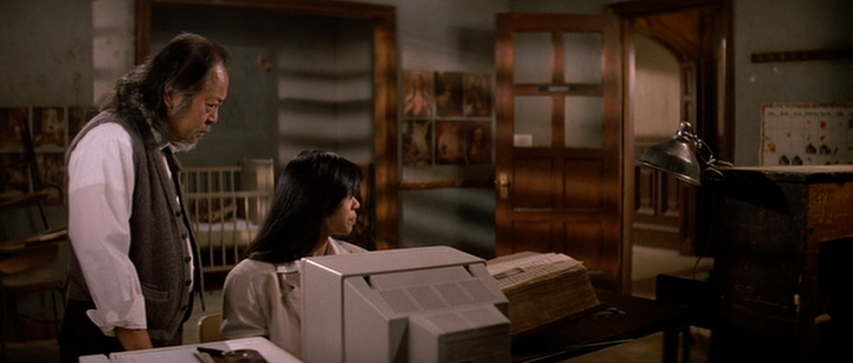

The priest knows this is too large a responsibility to fall to him alone, and he reaches out to quantum physicist Professor Birack (Victor Wong, the bus-diving wizard from Big Trouble in Little China) for help. Again, also not because Birack is in any way, shape, or form equipped the handle the problem, but because the priest has no other options.

One of my favorite things about Prince of Darkness is something we don’t actually see. In a one-line bit of spoken backstory from a completely different character, we learn that the priest and Birack participated years ago in a series of debates hosted by the BBC.

This debate series was certainly framed as a science vs. religion event, and we can easily see from the demeanor of the two men — and they way they interact — that the debates didn’t lead to any major conflict.

Instead, though they both view the world differently, applying the personal understandings that they believe in their hearts and minds to be true, they achieved a mutual respect. So much so that many years later they still wouldn’t hesitate to reach out to each other for advice.

Both the priest and Birack defer to each other as authorities in their disciplines, and the fact that they don’t clash and rather work together to fill in each other’s gaps is downright refreshing, and a far more interesting and rewarding narrative decision.

Prince of Darkness posits that science and religion are often two different ways of saying exactly the same thing. And “saying” (as in, consciously selecting the words you will use to express something) is important here.

The film’s central evil has been spoken about and recorded in various different ways throughout history. Indeed, one of the largest obstacles between our characters and an understanding of what they’re up against is the fact that The Brotherhood of Sleep’s texts have been rewritten and distorted many times for 2,000 years. “Writing upon writing,” the priest explains, “sometimes two or three times, and improperly erased.”

It’s not a simple matter of translating the texts; it’s a matter of being able to read them, understand which of the coexisting versions of the material are most important or most accurate, and deciphering why they were rewritten — or, I suppose, overwritten — at all. It’s a tangle of scripture and equations that probably made enough sense to The Brotherhood of Sleep, but are nigh on impenetrable to anyone else.

It’s up to a group of students recruited by Professor Birack and his colleague Dr. Leahy (Carpenter’s frequent collaborator Peter Jason, from They Live, Village of the Damned, Escape from L.A., Ghosts of Mars, Body Bags, and next week’s In the Mouth of Madness) to unravel the mystery of the canister and figure out how to keep it sealed.

What they learn is that the canister contains Satan.

…sort of. The canister contains the very real force that humanity has always understood as Satan. The Brotherhood of Sleep knew that whatever this evil thing really is would be beyond the comprehension of…well, pretty much everyone, themselves likely included. And so in absence of an understandable scientific explanation, they came up with and successfully circulated a spiritual one.

That’s why we — and the characters of the film — know Satan as a red-skinned demon with a pitchfork. It was an image that would stick, an image that would catch on, an image that although false would serve the purpose of warning people of a very real danger. It was — if we’d like to bring yet another discipline into it — a profoundly, globally effective marketing campaign. “Just say no to Satan.”

By painting this evil force as an untrustworthy imp with hooves and horns, the Brotherhood of Sleep rebranded the swirling green liquid for the masses. It is no longer something they could ever want to get close to, let alone study or analyze. In essence, had they attempted to explain it for what it actually was, there would have been necessary holes that their knowledge couldn’t fill, and others — especially through the generations — may have felt compelled to try to learn more and plug those gaps.

By more or less saying, “This is Satan, he will send you to Hell, do not tap the glass,” The Brotherhood of Sleep kept others far away. Ultimately the right decision and outcome. It was a lie for humanity’s benefit.

And so we gradually learn the scientific truths that religion rewrote (and overwrote, and partially erased), not to hide reality from us but to actually help us understand it in simpler, more accessible terms.

They say someone was cast down from Heaven rather than that Earth received a visitor from beyond the stars. They say that God works in mysterious ways rather than that the laws of physics break down at the subatomic level. They say that Christ is the son of God, our savior whose words must be adhered to, instead of saying that he was an alien who warned humanity that opening that canister would unleash a force they could not control.

It’s honestly a fascinating enough concept on its own, and Carpenter elevates it by having it permeate almost every scene in the film. He doesn’t leave the dual, complementary understandings of the world around us in the realm of the thematic; he brings it about through the set design with its religious symbols sharing the frame with scientific instruments, and the soundtrack with its synthesized choir. Every aspect of the film and its presentation ties back to science and religion overlapping, and it’s phenomenal.

Speaking of the soundtrack, my one hesitation with saying The Thing shows Carpenter at his best is the fact that he didn’t compose (much of) that movie. That’s not to say anything negative about the legendary Ennio Morricone’s work for that film, but it does represent one of the very, very few times Carpenter didn’t score his own material.

In Prince of Darkness, Carpenter directed, wrote (under a pseudonym), and scored the experience. He had his hands in all aspects of its production, which is why I think it holds together so well and might actually be the most cohesive of his films. You are surrounded on all sides by Carpenter’s vision, and it’s not a happy one.

The first time I saw Prince of Darkness, I admired it without enjoying it. I’m paraphrasing here, but a friend of mine once described The Fog as being a great movie in search of a good ending. For me, at first, Prince of Darkness felt like a great ending in search of a good movie.

This was without question my own fault. Somehow, in my mind, I’d accumulated a few details about the film that led me to assume it carried a much different tone. I knew it was about college students unleashing Satan, and I knew it starred Alice Cooper. Of course, both things I “knew” weren’t quite correct, but going into it I expected a much lighter experience than what I got.

It sounded like a sillier, dark comedy with some fun stunt casting. I figured Cooper would play a sort of showboating Father of Lies who would work with the kids and ultimately betray them, they’d learn too late that they were in over their heads, and it would be a fun little disposable romp.

It wasn’t that, and my expectations were so profoundly off the mark that it took me a long time to adjust to what it actually was.

Here’s what it actually was: bleak.

Everything about Prince of Darkness is so stubbornly, unrelentingly bleak. It’s stiflingly bleak. It’s disturbingly bleak.

I mentioned last week that some of the fun in The Thing comes from trying to pinpoint the moment at which the characters no longer have any chance of winning. You can’t really play that game with Prince of Darkness, because the characters never had a chance of winning. They started on the losing end and things only got worse for them from there.

And that’s what caught me off guard. Not the fact that evil triumphs or that bad things happen, but that nothing good occurs at any point.

Though, of course, that isn’t true. What Carpenter manages to do is frame even the small positive moments as bleak, making them feel unnerving and unwelcome. This resulted in what I first interpreted as a tonal mismatch, but what I now see as, simply, Carpenter’s vision of this particular little universe.

The film opens with things that really shouldn’t disturb at all. Students attending a lecture, the priest talking to some nuns. The Brotherhood of Sleep cleric dies, but he does so in his bed, without incident, quietly in the night. If Carpenter wanted to give us a miserable death he could have, but he gave us a peaceful death that still manages to read as miserable thanks to the blocking, the editing, and the creepy, pulsing dirge of the score.

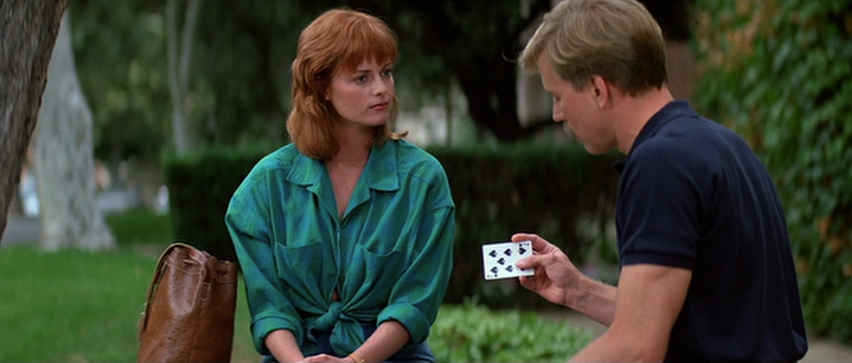

At another point in the introduction, a male student named Brian has an obvious interest in a female student named Catherine. He notices her and lets his attention linger. Then she’s joined by another man and they walk off, leaving Brian to assume they are in a romantic relationship. Oh well.

Carpenter films and presents this as though it’s absolutely harrowing. He presents Brian as a stalker and Catherine as his prey. When the other man arrives on the scene we feel a sense of relief because God knows what this guy had intended to do. It was certainly nothing good, the way he watches her from the darkness, not making himself known, dwelling…considering…planning…

And yet it’s not that. With an easy tweak of the presentation and honestly not much more of a tweak in the performances, this could be traditionally romantic.

The next time Brian and Catherine meet, they actually talk. They have a conversation. It turns out she’s not in a relationship. The two students make plans to meet up for a date. They do, it goes well, they have sex. They develop feelings for each other.

This is, more or less, the standard romantic template in film. But Carpenter never lets us feel the romance that they feel. He keeps it at a distance. We hear the soundtrack, which tells us to feel something very different from romance. We see where the camera trails off to find a too-busy nest of clicking ants.

The presentation is knowingly off-putting. As mundane things happen in the characters’ lives, we are never allowed to let our consciousness drift from the knowledge that this is a horror film. In one scene, Brian watches a science program on television. Big deal. Carpenter’s camera shows us the back of the TV, crawling and infested with insects.

The character sees one thing; Carpenter forces us to see another.

The romantic aspect of the film — which is honestly quite small — seemed so strange and out of place to me that first time. So much so that it interfered with my enjoyment of the movie.

It was weird and bizarre in a way it should not have been, or at least it seemed to be. I wondered why he was being such a creep. I wondered why she would be interested in such a creep. But that was just the presentation screwing with me.

Watching it while trying to block out Carpenter’s trickery, it’s just two college students flirting. At once point Brian makes a misjudged sexist joke, for which he immediately apologizes and she forgives him. They start over. This should be cute. The fact that it isn’t cute, or doesn’t feel cute, isn’t their fault. They didn’t choose what kind of movie they’d star in. If they could have chosen, it certainly wouldn’t have been anything like Prince of Darkness.

In another early moment, a homeless woman approaches the priest, takes his hand, and thanks him for reopening the church. It shouldn’t register as anything more than that, but it feels tense and sinister enough that we second guess the situation. Carpenter then shows us that she’s holding a cup full of rotted flesh, covered in writing maggots.

The priest enters the church and examines his hand, repulsed and haunted by what he’s seen. We’ll be repulsed and haunted, too.

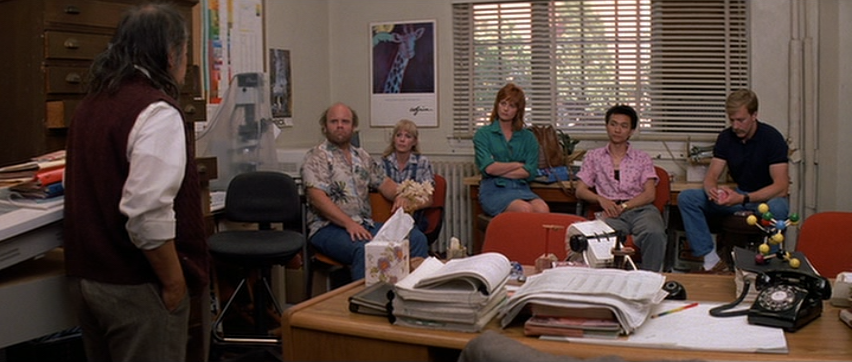

Because neither the priest nor Birack can solve the situation with the canister, they enlist the help of a number of students, Birack dangling the prospect of extra credit. Again, not because they are in any way, shape, or form equipped to handle the problem, but because there’s nobody else around to enlist.

The plan is that the priest, Birack, and Leahy will supervise the students over the course of the weekend, putting everybody’s talents and knowledge into the problem, working non-stop until they can be sure the problem is under control.

It’s a lot of work, but they figure they can solve enough of it quickly enough to at least keep whatever in in the canister at bay.

One student works to translate the Latin as best she can, but she can’t make sense of the complicated equations in the text, so she passes those on to another. One student examines the complex locking mechanism on the canister to figure out how it works, while another monitors energy readings. Some of them seem to be little more than sets of hands, rigging up the necessary equipment. Others are strictly intellectual, interpreting data handed to them and trying to fit it all together.

While Leahy keeps them hard at work, the priest and Birack sit in sequestration, talking bigger ideas, sometimes arguing, sometimes building on each other’s knowledge, working together to figure out what, if anything, they can do to keep Satan right where he is.

The expectation is that everybody will live in this church at least through the weekend, working any moment they aren’t eating or sleeping. And it’s honestly a pretty impressive representation of the kind of dynamics you’d expect to see crop up among a group of grad students.

The students look and act like average students. They mainly keep to their friends and hew close to their own professor. One warns another that a cute girl is married. They joke with each other. They drink beer and get on each other’s nerves.

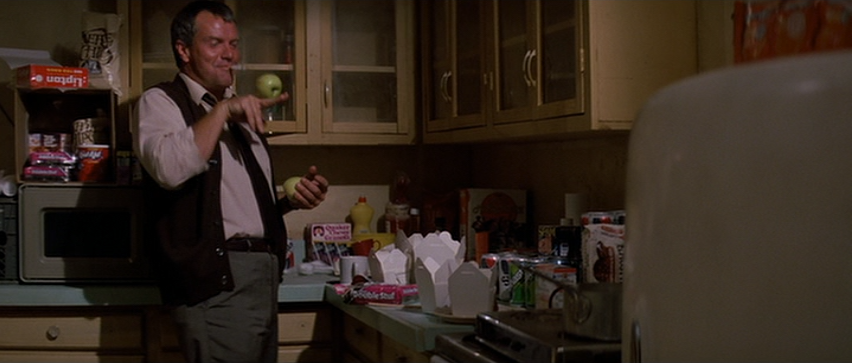

One of my favorite, perfectly human moments in any film comes when Leahy heads down to the kitchen for a snack run. He’s alone, but he amuses himself by bouncing an apple repeatedly in the air with his hand and forearm, trumpeting away through tight lips as he does so.

On his way out he passes a student watching cartoons, and he leans in to trumpet into his ear.

It’s a perfectly observed moment for anyone who has had exactly that kind of professor in the past. Someone who knows what he’s doing but also has a sort of rehearsed quirkiness and who makes sure you’re aware of it.

It’s an adorable little bit of business that immediately lets you know exactly how any conference and most lectures with Leahy are bound to go. Even with very little verbal characterization, you know precisely who he is.

The student he bothers at the kitchen table is played by Dennis Dun, who I thought was another tonal misstep for the film. He cracks wise and makes sarcastic comments and at one point even tells a complete joke — setup and punchline — while boxed into a closet by monsters. He’s comic relief, but he feels so out of place with what’s happening in the film that it’s irritating.

Of course, Dun was the deuteragonist of Big Trouble in Little China, a far more comedic film than we have here, and he was great. It’s taken me a while to warm up to his character in Prince of Darkness, but I think his comic relief falling flat is also part of Carpenter’s vision. Everything is bleak. Everything. Even in the presence of the guy who should keep things light now and then. He quips and jokes just as he should but the darkness refuses to retreat.

As they go about their work, they sleep in shifts. Sometimes planned, sometimes not. And when they sleep, they all have the same dream. They may not see all of it, but the dream repeats like an S.O.S. message…which is exactly what it is.

The dream is heavily distorted, a broadcast over a weak signal. They see the exterior of the church they are in. A dark figure appears in the doorway. A garbled voice croaks a warning we can barely make out.

The priest recognizes it from the cleric’s journal and explains the dream to them. It is indeed a broadcast…from the future. From this very spot. Something terrible has happened. Something unstoppable has been loosed. Somebody in the future is sending this distress message back in time, to anyone within the immediate vicinity, warning them, pleading with them to help.

This is what we see of the apocalypse in Prince of Darkness. In The Thing, it was a computer simulation. Here it’s an actual, direct broadcast of what is going to happen if the team can’t solve the problem. In the future, it’s too late to stop the apocalypse. Their only hope is to broadcast into the dreams of someone in the past — anyone in the past — who can stop it before it begins.

It’s a desperate gamble — a Hail Mary, if you will — but it’s all the future’s got.

While the team tries to figure out what to do, the contents of the canister establishes again and again that it’s beyond their ability to either comprehend or control.

Satan, though contained and weakened for two millennia, has enough power now to control small things. Insects. Nearby objects. Even the homeless. If he’s not outright controlling them, he’s at least influencing them, drawing them near, interfering with their minds. They surround the church to prevent anyone from leaving, and eventually barricade the doors.

When one student leaves, he’s approached by a hobo played by Alice Cooper — see! I knew he was in here somewhere… — and impaled on a bicycle.

When another (Robert Grasmere, who worked on the visual effects in this film and also had a non-speaking role in They Live) leaves, he’s stabbed to death. He then returns later, animated by insects long enough to deliver a warning (“Pray for death.”) before the bugs abandon his corpse and let it collapse.

Of course, staying inside the church isn’t any safer. At one point in the film, Satan has enough strength that he’s able to shoot a jet of the green liquid into the mouth of one of the students. She gags and stumbles around helplessly, and is soon…well, not quite possessed, but certainly not herself.

“Worker ants, driven to a higher purpose, unknown to the individual. Street people…our colleagues,” Birack says. “All controlled.” A student asks if it’s demonic possession, and Birack makes a distinction. “Of a kind,” he says. “Not what we would expect, though. Never that.”

As more of the characters are overcome, we can understand that distinction more clearly. As in Get Out, one’s consciousness is not replaced; it’s just relegated to the passenger seat. It’s still there, it’s still present, it’s still aware, but it’s no longer driving.

That’s why each of the hosts for Satan acts somewhat differently.

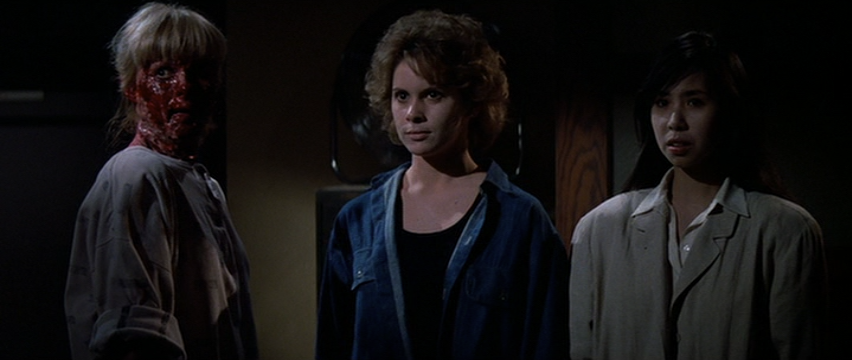

Lisa — Ann Yen, who has the best blank stare I’ve ever seen — types madly away at a keyboard, serving as a medium for Stan exactly as she did for The Brotherhood of Sleep when she was translating their texts. Leahy stumbles around, barely able to move, weeping over the fact that he’s no longer himself. But the most interesting host is Calder, played by Jessie Lawrence Ferguson.

In one of the film’s many unspoken bits of quiet characterization, Calder wears a cross necklace when he arrives at the church. Aside from the priest, he may be the only Christian in the film. We can’t know that and normally it wouldn’t matter, but when he’s overcome he wanders around, emptily singing “Amazing Grace.”

It’s not Satan singing that song through him; it’s Calder, fighting his possession. And when he senses that he’s going to lose the fight — fight he probably only had in him due to his faith — he slits his own throat to prevent himself from becoming one of Satan’s minions.

Of course, as we already saw with the bugs puppeteering another corpse, Satan in this film has the ability to keep his unwitting helpers going after death. Calder reanimates and wanders the church. He eventually finds a mirror and stands in front of it for almost the entire remainder of the film, transfixed. He sees himself. He sees the fact that he slit his own neck to escape from this nightmare. He sees that it has not worked.

And he laughs. He laughs and laughs and cries and laughs, because he knows there’s no way out. He knows that’s him in the mirror, but also not him, and that there’s nothing he can do about it. It’s absolutely chilling, and so perfectly executed.

Aside from giving Calder just a little bit of strength in his still-doomed struggle against Old Scratch, though, what role does faith play in Prince of Darkness?

Well, it plays the most important part, though it’s too late to do any good.

One of the characters examines the canister and figures out that it’s locked from the inside. While that might seem like a pretty massive design flaw when your prisoner is The Angel of the Abyss, it makes sense. If The Brotherhood of Sleep wished to prevent future generations from letting him out, placing the lock on the inside would solve that problem.

Of the problem of Satan unlatching his own cage, though, that’s where faith comes in. As long as stories of Satan’s evil circulate and are believed, as long as mankind wants nothing to do with him, Satan remains weak, unable to open the complicated lock on his own prison.

As the years ticked by and humanity became more scientifically literate, the number of people who understood the world through an entirely spiritual lens necessarily decreased. Not a problem in itself, but with fewer people giving Satan the time of day, his power grew, and grew, until we reached this moment, the moment at which he can begin to reassert dominion and wriggle loose of his bindings.

“It’s your disbelief that powers him,” the priest tells Birack, in the closest thing to true conflict they have. “Your stubborn faith in…in common sense…that allows his deception.”

He tells Birack that they need to spread belief again if they are to weaken him and keep him trapped.

“You must prove it scientifically,” he says, knowing even as a priest that Bible stories won’t cut it. “Convince the outside world.”

Birack, though, replies with a harsh truth: “The outside world doesn’t want to hear this kind of bullshit.”

And he’s right. The world has moved on. No scientist declaring that Satan is real will convince the masses to convert, to believe, to fear something they’ve already dismissed as legend. The best they can hope to do is to keep it imprisoned, and with every second that ticks by, it gets more and more difficult to do so.

Keep this in mind, by the way, for next week. Here, a lack of faith gives the enemy strength. In the Mouth of Madness will show us the exact opposite.

Actually, hey, as long as we’re connecting this to the other films in the trilogy, a student in Prince of Darkness says, “Faith is a hard thing to come by these days.” This is an almost exact lift of MacReady’s line in The Thing: “Trust is a tough thing to come by these days.”

And Calder laughing madly when he sees his helpless self reflected in the mirror? Sam Neill will do something very similar with a movie screen next week.

Anyway, the film doesn’t so much build toward its conclusion as it collapses toward it…which I mean as a compliment. Even the first time I watched Prince of Darkness and disliked it, I thought its ending was phenomenal. And still, even now, I think it’s the film’s runaway highlight.

Having made absolutely no headway toward keeping Satan contained, the few characters who don’t already serve as host to The Deceiver of the Whole World can do little more than lock themselves in tiny rooms and hope for a miracle. Or, in the priest’s case, pray for one.

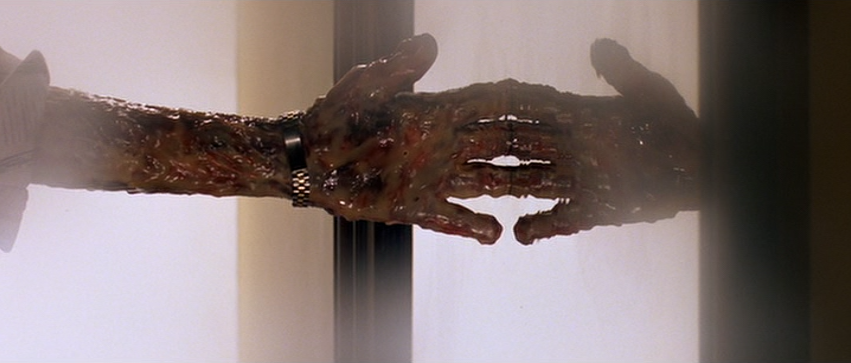

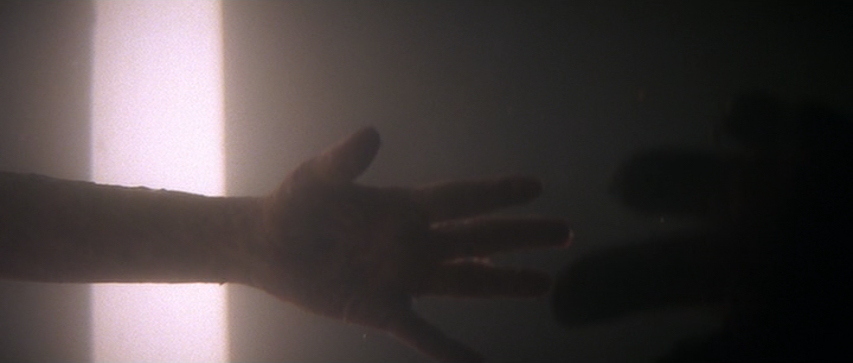

One of the students serves as a dedicated vessel, and has the ability to reach through mirrors into another universe…a universe in which the more traditional, physical manifestation of Satan waits. Technically he’s referred to as this Satan’s father. The end result is the same; the scientific Satan on this end reaches across the boundary to the spiritual Satan on the other.

In such a simple, brilliant special effect, Carpenter films the surface of calm water as the surface of a mirror, and the image of the vessel reaching through to take the hand of The Devil is striking and immediately memorable.

She begins to pull him through to our world, and all is as good as lost.

Catherine realizes that this is their last chance to force evil back. She dives at the vessel and tackles her.

They fall through the mirror, leaving The Devil where he is. And before anybody can even try rescuing Catherine, the priest destroys the mirror with an axe.

She’s trapped. She’s gone. She’s stuck, alone, with the Prince of Darkness.

It’s such a perfectly unexpected moment, and yet thoroughly fitting. We expect our heroes to either live or die. It’s rare to see a character — especially one as sympathetic as Catherine — be sealed away in the depths of Hell for the crime of saving the world.

It’s an absolutely chilling fuck-you to the character. Not from Carpenter, but from the universe. And it’s so God damned perfect.

But it’s over. That’s the important thing. After several long nights of losing every battle, they’ve won the war. Catherine is gone, but so are many others. What matters is that they came out on top.

“We stopped it,” the priest says to Birack as a new day dawns. “We stopped it here. Through the grace of God, I stopped it. The future conjured up by that vile serpent will not happen now.”

It’s a time for gratitude, for thankfulness, for relief, for remembering those who died to keep the apocalypse at bay.

And then Brian has a dream. The same dream. The broadcast from the future. And this time, he can see the mysterious figure more clearly: It’s Catherine.

They stopped nothing. It was always Catherine in that vision. Always Catherine that served as Satan’s vessel in the future. That was always what was going to happen.

They didn’t fight it or postpone it at all. Everything happened the way it was always going to happen.

At least, that’s how I’ve always interpreted it, and I have difficulty seeing it any other way. I’ve read reviews and summaries that say the ending is inconclusive, or even that the characters manage to succeed at the last moment.

And I suppose I can see where they might get those ideas. Carpenter admittedly doesn’t end his film with a title card reading “THEY’RE FUCKED.” But I think Carpenter gives us enough reason to believe that the apocalypse has not been averted. (And the film being part of something call the “Apocalypse Trilogy” is only one of those reasons.)

I think the decided bleakness of the entire experience is crucial. That’s why we have to accept that when Catherine falls through the mirror, in an act of massive self-sacrifice, nobody is saved. Her act, structurally, needs to be meaningless, lest Carpenter undo every bit of groundwork he’d spent 90 minutes laying.

Throughout Prince of Darkness we are not allowed to laugh at jokes. We are not allowed to feel good about romance. We are not allowed to believe at any point that these characters have any chance of making any amount of progress. For Carpenter to undermine himself at the very end, for him to give the characters a victory — however Pyrrhic — would be for Carpenter to betray his own achievement.

No. Catherine is gone. That is both a nightmare and reality. That is what makes the movie matter. For all the blood and trauma and madness of that weekend, everybody ended up where they had to be for the apocalypse to come to pass.

At the end of The Thing, it’s possible the characters have succeeded in saving the human race. At the end of Prince of Darkness, the characters probably have not. As we will see, at the end of In the Mouth of Madness, the characters definitively haven’t. These films build on each other toward more conclusively tragic endings. If we allow ourselves to believe that good triumphed over evil in Prince of Darkness, the film loses its place in that progression.

To put it more simply, nothing about Prince of Darkness was happy. Why would its ending be?

Of the Apocalypse Trilogy, The Thing is pretty much universally considered to be the best. And as much as I love to argue…I can’t argue with that. It is the best of the three films, in almost every regard.

But Prince of Darkness is my favorite. It’s just so remarkably effective at what it does — and is bravely uncompromising in its bleakness — that I can’t help but admire it.

After I watched it the first time and disliked it, I still thought about it, constantly, for days. Honestly, it may even have been weeks. It haunted me. The feelings it triggered in me never subsided for long. It was always there, on the other side of that mirror, waiting.

And now, after I’ve seen it another five or six times, I love it. The Thing was always great, and though it grows a little bit in my estimation every time I see it, Prince of Darkness grows by enormous leaps each time. It started in a position that didn’t impress me, but improves so much each time that it’s a kind of dark miracle.

It’s also the scariest of the three films, and for my money the scariest Carpenter film overall.

I mentioned last week that nearly every Carpenter film is about the characters figuring out the rules of the universe they inhabit. I think the characters in Prince of Darkness are the ones who make the smallest amount of progress toward doing that.

Which I love, because it’s realistic. Carpenter puts his characters up against an evil so towering and unknowable that they can only be conquered by it, and then he lets that defeat unfold step by merciless step.

It’s cruel, and at no point does it pull any punches.

After all, I promise you, if Satan is clawing his way out of some underground container in our world, we aren’t smart enough to cram him back in there, either. We’ve also stopped recognizing evil for what it is. Someone probably could have stopped it a long time ago, but if you look around right now, I’m sure you’ll agree they didn’t.

And now what will happen, will happen.

I wish us all better luck next week, when we’ll look at In the Mouth of Madness.

I wasn’t keeping an eye on the dates of when the review dropped so it’s fortuitous that I happened to rent Prince of Darkness (and In the Mouth of Madness) last night in preparation for this.

I didn’t care for it, for some of the reasons you had in your initial viewing and I doubt my viewing habits these days will permit a re-evaluation anytime soon, if ever. I did enjoy the occasional crucifix imagery made out of the glazing/muntin bar of the interior door windows though.

I do believe/theorise that the ending is deliberately ambiguous because Brian the moustachioed letch could just be having a nightmare from his traumatic experience what with no-one being there to share it.

This movie is the ultimate definition of Irony.

The dream is supposed to change according to how the movie progresses . First it was the Father, then it was Calder and finally Catherine.

Just how bad is 1999 than the only solution was to send a message to the past (And this message repeating since the 1950 to the year of the movie, which also means that the beam was targeted to all the previous locations of Earth?)

About the dream…. I think that it was Walter the one that sends it from the future. This explains why Brian got the message at his home in the end and didn’t had it before.

My thoughts on the movie go back and forth. What I do not doubt, however, is the terrific electronic score, by Carpenter and Howarth. A character in its own right.

I came here to pinch a picture of Calder, as I was making this exact same argument in a discussion on Quora.

You make all the same points I made (and more) but far more succinctly.