This year we’ve already looked at three films featuring games that celebrated, encouraged, accelerated death. With Solarbabies, we cap off the year with one featuring a game that brings life. In each of these films, a heinous social order is upended. It’s only Solarbabies, though, that stays true to the prediction of Gil Scott-Heron; its revolution is not televised.

Solarbabies is also, by quite a wide margin, the worst actual film I’ve ever seen.

By “actual film” I just mean we can totally ignore homemade crap like The Lock In. Of any movie that’s ever had actual effort invested in it by actual human beings with actual equipment, Solarbabies has got to be the worst.

Which, of course, makes it pretty fucking wonderful.

It feels like it’s cobbled together from several scripts of totally different genres.

It’s an action movie, a sports movie, a post-apocalyptic nightmare, a road movie, a coming of age tale, a journey home, a science fiction saga, and God knows what else. It drifts into both body horror and torture porn. There’s even just enough attempted romance in it that I’m willing to believe that someone on the production staff thought that should be at the heart of it as well.

Maybe I shouldn’t distance Solarbabies from The Lock In after all. In each case, the directors had a scatter of ideas they thought would make for a good film. In each case, the filmmakers had no idea how to assemble those ideas, what to leave out, or even how movies work. The only real difference is that Solarbabies wasted a hell of a lot more money trying.

The movie opens with narration, as all truly terrible movies must. It tells us nothing we won’t learn more naturally throughout the course of the next few scenes, but Solarbabies doesn’t give itself any more credit than the rest of the world does.

We’re told that the Earth is dry and largely barren. An organization known as The Protectorate controls all of the water, but a tribe called the Tchigani believe a space creature named Bodhi will eventually come and spray water everywhere for free.

It’s a lot of information, and unnecessarily specific, but it’s delivered by the late, great Charles Durning, so that’s nice. It’s also pretty weird, though. He introduces himself (still in narration, to whomever the fuck you’d like to believe he’s speaking to) as the Warden of Orphanage 43. “Children are brought here at an early age to be indoctrinated to serve The System,” he says. “It hurts me to do what I do. I, too, must serve The System.”

All of which, you know, sort of implies his character will have an arc in the film, or at least some relevance. Instead, yes, we see the Warden a couple of times in the opening scenes, but then he disappears forever.

That’s okay; a lot of characters disappear in a lot of movies. What’s far less common, though, is that the damn narrator disappears.

You can do a lot with a distant narrator in fiction. It can be part of the fun and part of the artistry. Nick Carraway narrates the love story that is The Great Gatsby without any personal experience of love himself. John Dowell narrates The Good Soldier without ever understanding the story he’s trying to tell. Charles Kinbote narrates Pale Fire with a complete refusal to let you read the story you bought the book for; he has a different story he’d like to tell, thank you very much.

The Warden, by contrast, has no reason whatsoever to open Solarbabies with his in-character narration. He might as well say, “Let me explain what happened during this adventure I played no part in, wasn’t present for, and couldn’t possibly know about.”

The actual narration ends on a note only slightly less ridiculous than that. After speaking about the Tchigani / Bodhi crap, Durning says, “Is this legend true? Who knows.”

Seeing it in print, it works well enough. In speech, though, Durning comes across like a not-entirely-sober old man who can’t remember what he wanted to say. The opening narration works hard to provide so much background, and then ends on the possibility that none of it was worth listening to.

I’m telling you, Solarbabies is great.

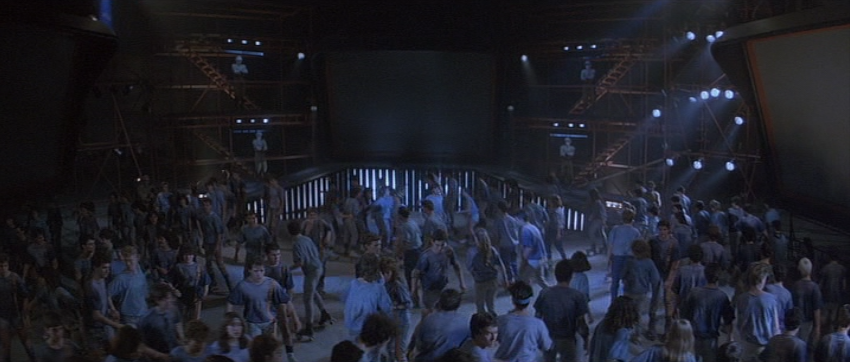

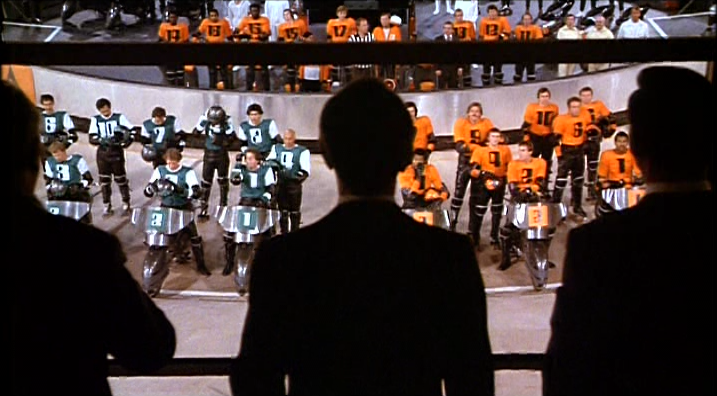

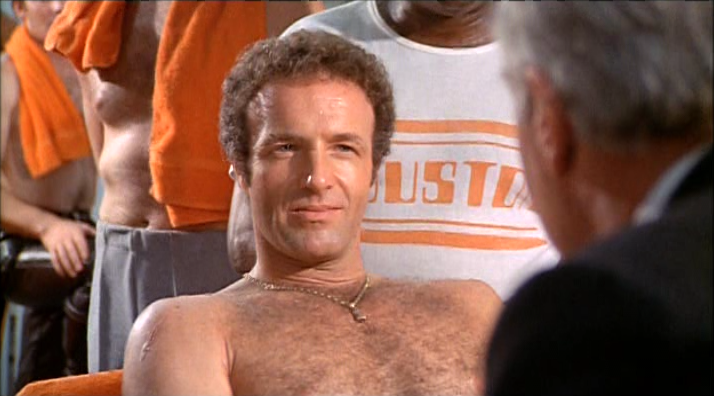

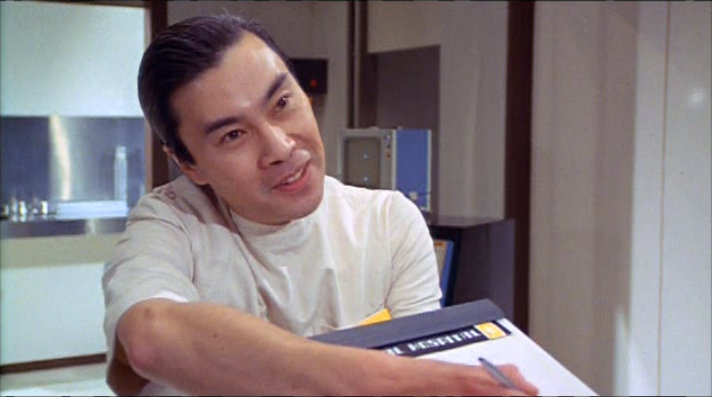

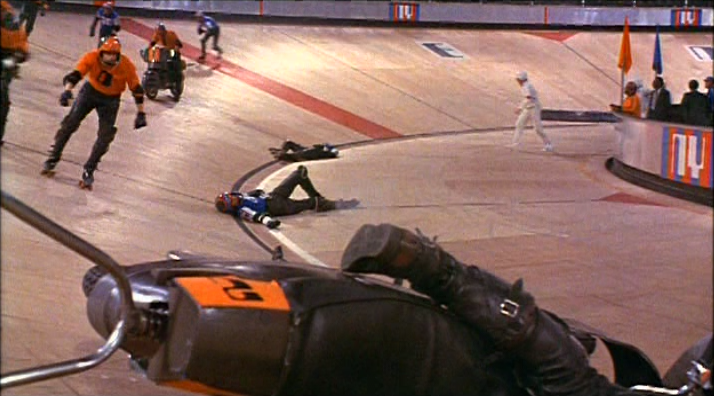

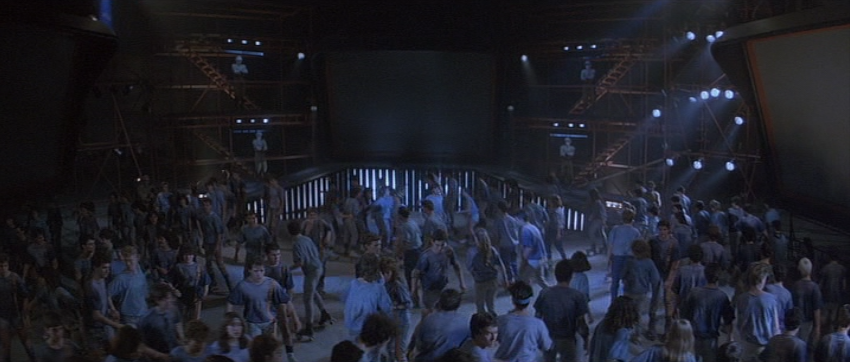

Things don’t get much less confusing from here. We are launched right into an early-morning game of Skateball, which is named that because somebody on the crew must have realized late in production that Rollerball was taken.

Skateball is played with lacrosse sticks and a basket that stands upright in the center of the rink. After watching Rollerball, I understood both how the game was played and why it was so compelling. After watching Solarbabies I have no clue why Skateball is any more interesting, important, or meaningful than any other game kids might play at recess. We may as well be watching a movie about futuristic hopscotch.

Anyway, the kids sneak out of the orphanage ready to play an intense game of Skateball. A different little kid turns on some stadium lights and is spooked by a spider. Yet another kid rollerskates down a crane and an owl lands on him.

It is the greatest movie ever made.

The match is between two teams: the Solarbabies and the Scorpions. It sucks.

The one kid is here because they need someone to turn on the lights who is also disposable enough to potentially be killed by the spider, I guess. The kid with the owl serves no purpose here whatsoever.

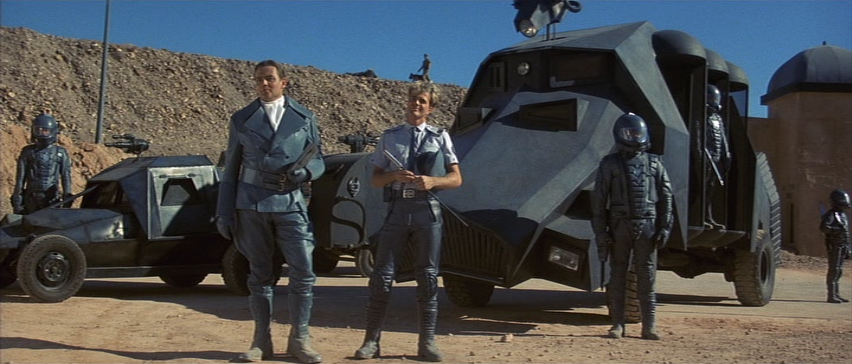

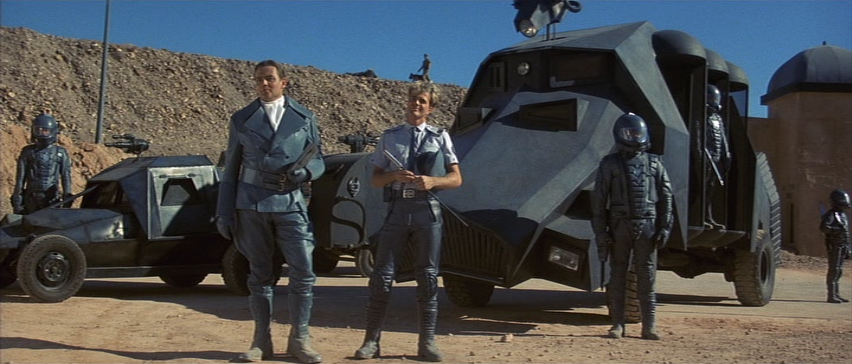

The game progresses firmly in the Solarbabies’ favor, but then some cartoon Nazis show up and shut it down. It turns out Skateball is illegal, giving us our central conflict for the film.

Only joking. That would give us a central conflict for the film. Instead, the cartoon Nazis are mad because this rink is outside the grounds of the orphanage, and there’s a Skateball rink within the grounds of the orphanage that the kids are supposed to be playing Skateball on.

…alright.

This would be fine if we learn later that the illegal Skateball rink was too close to some kind of Protectorate secret or something, which would warrant the armed response to idiot children rollerskating in a circle, but no. The cartoon Nazis bring tanks and laser guns because the Solarbabies should have been playing in a different rink a few yards to the east.

And, maybe it’s just me, but if the fucking cartoon Nazis have to put all their gear on and load up their armored assault vehicles every time some kids use the illegal rink, why not destroy the illegal rink and never have to worry about it again?

As I’ve said, this movie is very, very good.

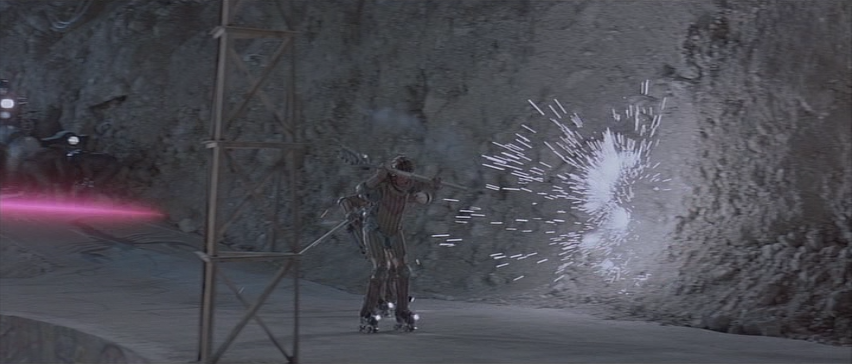

The Solarbabies scatter while the cartoon Nazis shoot at them, attempting and failing to execute children for rollerskating on the wrong patch of concrete.

If you’re wondering why I’m not using anyone’s name it’s because we haven’t been properly introduced to anybody yet. Then again, I’ve seen this movie a few times and I still don’t know most of the Solarbabies. There’s the girl one, the black one, the glasses one, and two other guys who look way too much alike to ever register as distinct characters.

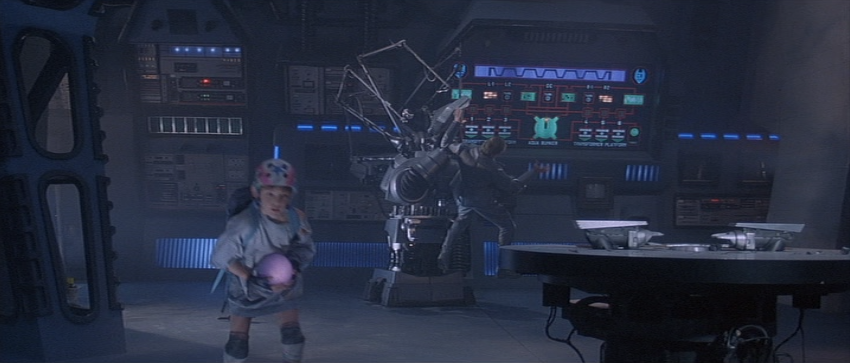

The little kid who made a face at a spider ends up in some catacombs, I guess.

He’s an idiot, so he releases the break on a mining cart that for some reason runs straight into a wall, which is as thin as Styrofoam and, coincidentally, breaks like it, too.

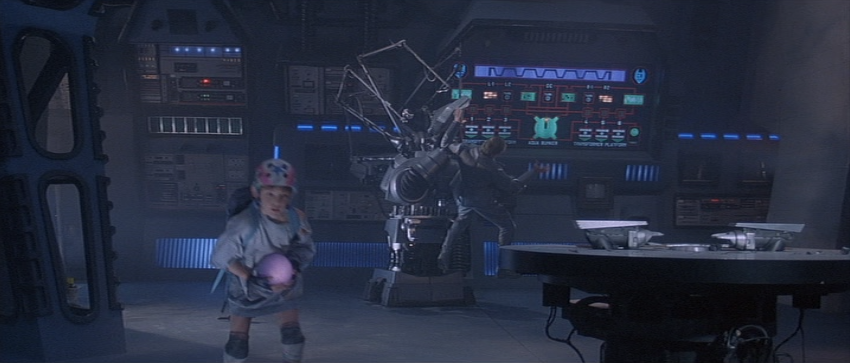

Behind the wall is some secret cavern where a magic, glowing ball lives. I guess the miners should have tunneled one more molecule in that direction before giving up for the day. We could have watched a movie about them instead of the Solarbabies.

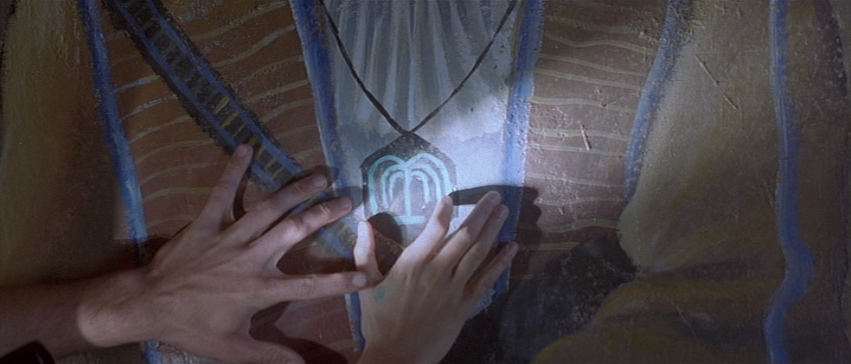

The kid touches the ball and then emits the most irritating sequence of shrieks imaginable. Sadly, he’s not in immense pain. It’s because he can hear now.

“I can hear,” the kid tells the ball. “You did it. You fixed my ears.”

Oh, did I forget to tell you the kid was deaf? So did the movie, so don’t worry.

I mean, we do see him wearing headphones, which we later find out were some kind of device that helped him hear, but if the movie wants a big moment when a magical creature fixes some kind of medical problem, we should probably know the medical problem exists before we’re assured it’s cured.

If you see me dying of cancer for months and months and then I touch a glowing space ball and I’m instantly cured, that’s magic. But if you have no knowledge of me ever having had cancer and I tell you one day that I totally did but a glowing space ball fixed it you’re just going to think I’m an idiot.

Don’t worry; I won’t describe this thing scene by scene, but this particular moment demonstrates the truly bizarre narrative approach taken by Solarbabies.

See, in most narratives, the characters start somewhere and make progress toward something. In the end they may find it or they may not, but that journey is part of (and often is) the narrative experience. Consider Scrooge’s emotional journey in A Christmas Carol, Ahab’s single-minded, suicidal vengeance in Moby-Dick, Odysseus’s long trek home in The Odyssey.

Or, y’know, consider literally any story you’ve ever enjoyed. The characters are in some kind of position (whether emotional, psychological, logistical, physical, professional, geographical) and would like to be in a different one. Their progress from one to the other (or failure to progress) is what makes a story a story.

Solarbabies treats story like a light switch. Instead of featuring a bunch of characters progressing toward any kind of goal, problems are resolved as quickly as they’re introduced. It’s like the script was written as some kind of cinematic experiment in flash fiction.

First there’s the deaf kid. By the time we learn he can’t hear, he can hear. There’s no chance to identify with the character’s struggle, no way to invest in his journey, and no opportunity to share in his triumph. There shouldn’t even be punctuation between these two states in the Solarbabies plot summary. It should read something like, “He’s deaf actually not anymore.”

This happens again and again throughout the film. The narration says there’s a legend Bodhi will come to Earth, and we immediately see Bodhi come to Earth. The Solarbabies think one of their friends might have died in an explosion, so we find out immediately that she didn’t. The Solarbabies are captured by bounty hunters, and then they are immediately freed. We see a mysterious symbol drawn on a wall and are told it looks like the mark on one of the Solarbabies’ hands…even though we were never shown or told about that mark on her hand before.

Nothing is set up and then resolved. The setup and the resolution occupy the same space, over and over and over again. If Solarbabies director Alan Johnson did a version of Moby-Dick, it would be eleven seconds long. It would open with Ahab saying, “I really need to find that whale oh there he is boys get him.” It would probably be narrated by Ishmael’s middle school geometry teacher.

Another example of setup and resolution comes soon after the littlest Solarbaby finds Bodhi, and it leads to an even bigger problem with the film.

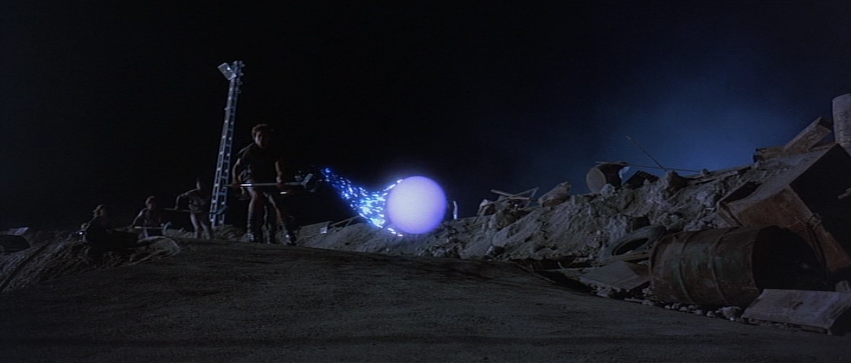

He hides Bodhi in a trunk, which I guess the Solarbabies keep around even though they have nothing to put in it. Fine. The rest of the Solarbabies come in and start talking about how nice it would be if they were ever able to experience rain.

It immediately begins raining in the barracks, and the Solarbabies dance in it.

This movie was released in the mid-80s, remember, back when studios would be fined heavily if their characters didn’t stop to dance at least twice per movie.

So, once again we see Solarbabies‘ innovative approach to storytelling. “What if X happened hey look X is happening!” But we also see the massive logistical hole at its center.

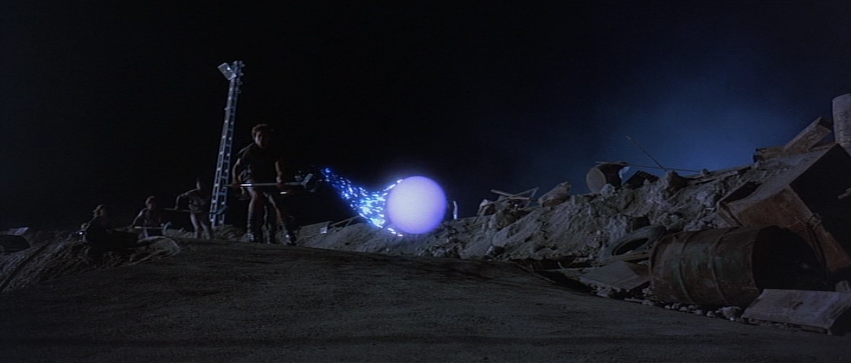

If Bodhi has come down from the stars to restore water to the Earth and he can make it rain just to baffle some idiot teenagers, why does he never do so again until the end of the film?

It would be easy enough to say that Bodhi doesn’t have his full powers yet, or he has to charge up his abilities for some set period of time or something, but that never comes up. He can generate storms from nothing, on command. He does it here. At the end of the film he does it again, on a larger scale, immediately restoring the planet’s oceans, lakes, and streams.

So…why didn’t he do this earlier? What was stopping him? I know we wouldn’t have a film if Bodhi worked his aquatic mojo in the very first scene we met him, but Bodhi doesn’t know that. What’s stopping him from doing the thing he was sent here to do? It’s not as though he’s busy doing anything else; he spends the entire movie sitting in people’s backpacks. Get to work, you lazy shit! People are dying!

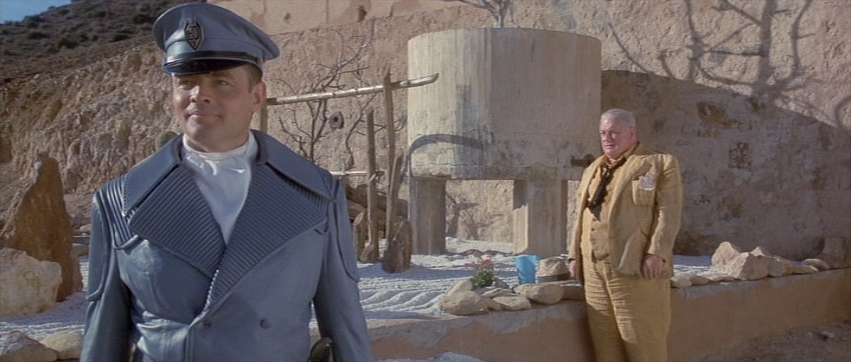

Anyway, the main cartoon Nazi is angry because the Solarbabies skated at the unsanctioned skate park that is totally off limits even though nobody’s even bothered to so much as put a fence around it. He yells at the Warden to punish the Solarbabies. The Warden says he will punish the Solarbabies and the Scorpions. The cartoon Nazi says no just punish the Solarbabies. The Warden says he will just punish the Solarbabies.

Then the cartoon Nazi reveals that he has some kind of futuristic hot Nazi stick that can burn things. You might think this is setting up a time that he will use it to burn things later in the film but you’re watching Solarbabies.

It’s a strange scene, mainly due to the absence of the cartoon Nazi bitching about Skateball. This is the scene where the antagonist should say something like, “I don’t like this ‘Skateball.’ It gives the children hope. It makes them laugh and smile. It’s a frivolous activity that takes time away from their work and their studies, and I insist you put a stop to it immediately, Warden.”

But the cartoon Nazi actually does like Skateball. He just prefers the Scorpions to the Solarbabies. The Warden likes Skateball, too. Everybody likes Skateball! Skateball! The one thing kids and their fascistic oppressors can agree on!

In fact, The Protectorate teaches them to play Skateball, and they hold orphanage-wide Skateball practice, and have all the kids do choreographed Skateball stuff. You’d think this is some kind of indoctrination, and maybe it is, but I sure as hell couldn’t tell you how.

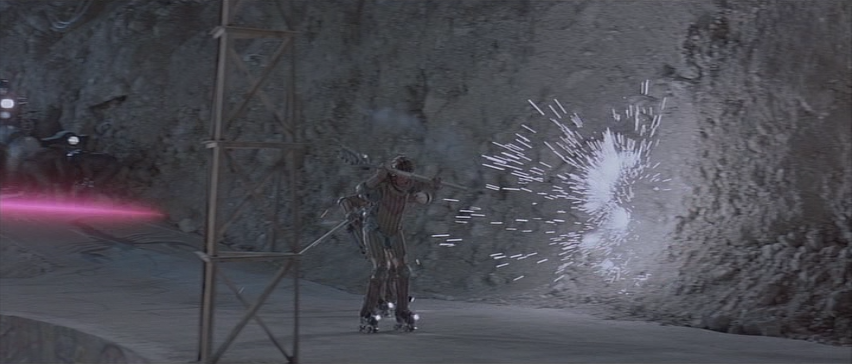

The Protectorate is, for some reason, training all the kids to skate real good. This is great for the kids, because when the Solarbabies go on their adventure they solve every problem by skating real good.

But why is The Protectorate interested in turning them into skating prodigies? Maybe if the cartoon Nazis all skated around it would make sense, because then skate practice could be a kind of subtle training regimen, but the cartoon Nazis don’t skate at all! In fact, the Solarbabies’ ability to skate real good is the only thing that allows them to escape from and defeat the cartoon Nazis. The Protectorate is actively training kids to escape The Protectorate.

One of the kids on the Scorpions is even a cartoon Nazi, and he can skate real good, too, but even he doesn’t skate while in pursuit of the other kids who can skate real good! He can match their skating abilities and he doesn’t do it! So why the living fuck do the cartoon Nazis teach people to skate?

Also, to make sure we know he’s bad, he keeps trying to rape the girl Solarbaby. It’s a wonderful film if you haven’t seen it.

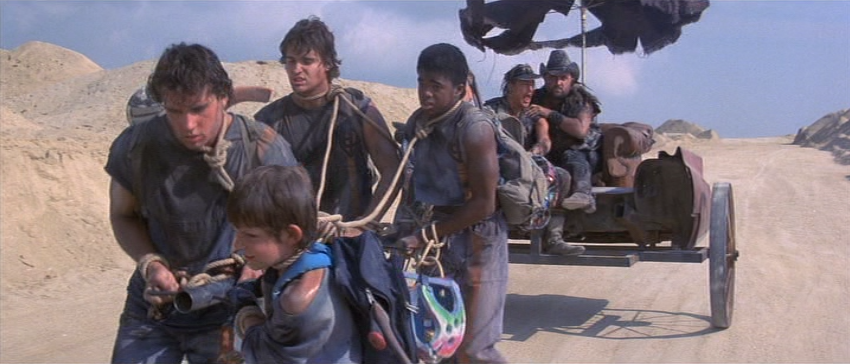

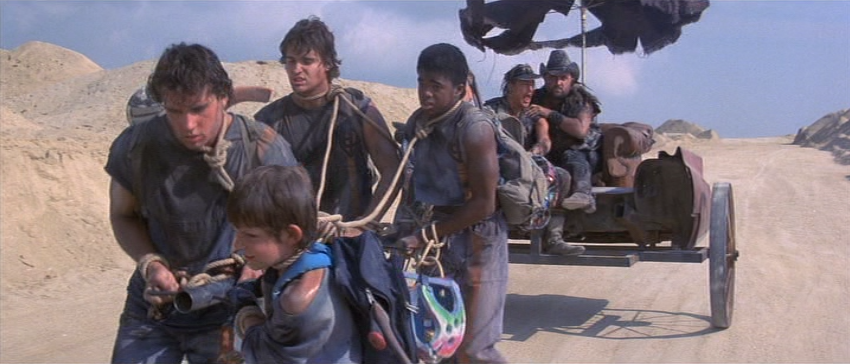

The kid with the owl steals Bodhi and escapes the orphanage to find his tribe, because he’s a Tchigani. The not-deaf kid then escapes the orphanage to find Bodhi. The rest of the Solarbabies then escape the orphanage to find the not-deaf kid. Try locking your fucking doors, Warden. The cartoon Nazis then leave to find the Solarbabies. It’s a chain of morons chasing each other through the desert, and it seems like a setup for one of those scenes in Scooby-Doo when everybody chases each other through doors in a long hallway.

That’s absurd enough, but the fact that all of the kids are rollerskating through the desert is so beautifully idiotic that I can’t help but love it. At first, near the orphanage, I was willing to believe there were maintained roads just beneath the surface of the sand. But as the kids venture deeper into what is referred to as the wasteland, they’re still skating perfectly fine. Over sand! Over rocks! Over the fucking ruins of civilization!

Of course, this is because their training as Solarbabies has prepared them to defy the laws of physics and/or topple the government. There’s a scene during the escape when one of the Solarbabies uses his particular set of Solarbaby skills to deactivate a security camera. And by “deactivate a security camera” I mean smash it with a rock.

Sure, he uses his officially licensed Solarbabies lacrosse stick to launch the rock, but the camera was right there on the ground. He could have just walked up and kicked it. Fucking showoff.

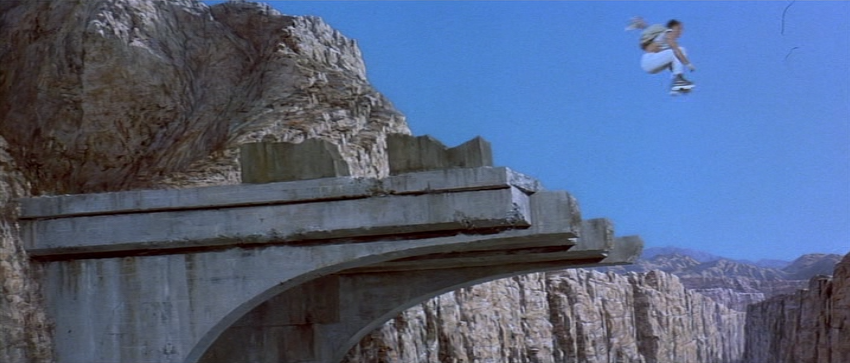

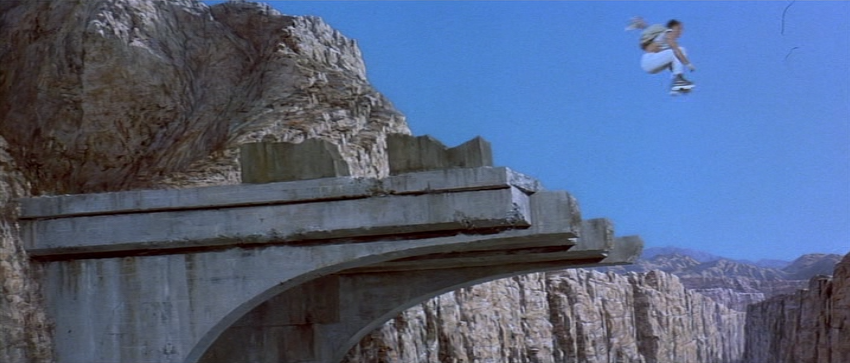

At one early point in their adventure, the Solarbabies are pursued by two cartoon Nazis on motorcycles. To escape, they’ll have to skate real good. Fortunately, the Solarbabies can skate real good!

They skate real good right over a big gap in a bridge, and the cartoon Nazis can’t motorcycle real good so they have to stop, only one of them falls off the edge of the bridge and his motorcycle explodes, blasting his limbs off and cooking him alive.

The Solarbabies cheer their success / this man’s grisly, flesh-melting death.

In fact, I know the Solarbabies are our heroes and all — they’re off to rescue Bodhi, who could have already saved the world in the opening few minutes and let’s not focus on that — but they sure do kill a lot of people along the way.

And it’s not even one of those, “I wish there were a more peaceful solution…” kind of things. The Solarbabies kill and quip as they electrocute people, blow people up, destroy their cities, shove them down holes to get eaten by angry dogs, and get them attacked by malfunctioning robots that drill them to pieces. Admittedly, a good number of these people are cartoon Nazis. A larger number of these people, though, are bystanders or guards who are just doing their jobs and have genuinely no clue what the hell is going on.

At no point does any Solarbaby say, “Hold up, gang. We’ve killed an awful lot of people today. Do you think maybe we should chill out a bit?”

The Solarbabies are supposed to be sympathetic characters. We’re supposed to want them to win. But watching them singlehandedly decimate the formerly peaceful settlement of Tire Town, reducing it to a smoking crater of bodies, it’s hard to think of anything they’re doing as remotely heroic.

In fact, isn’t the whole problem with the Nazi guys that they go into these different towns and wreck them up and burn them down? What the fuck are the Solarbabies doing?

And, again, they aren’t restoring water to the world, which might be worth disemboweling a few hundred thousand innocents. Bodhi is going to do that. He’s just…I dunno, busy brainstorming a novel or something.

I find it very important to keep in mind as you watch the Solarbabies death toll climb that Bodhi could, at any point, do the spheric equivalent of snap his fingers to immediately bring water to the world and remove entirely the need for any further senseless death.

Of course, I don’t think Johnson had any clue what the hell Bodhi was, or what his motivations for saving Earth would be, or how any of this was supposed to work. He knows Bodhi can’t restore the planet’s waters until the end of the film, so that’s when it happens. Beyond that, Johnson has no clue.

Bodhi communicates telepathically with the Solarbabies, but we get conflicting information on how. Sometimes he shows them vague visions meant to suggest their next steps, and sometimes he must speak directly to them in clear English, such as when he teaches them to pronounce his name. Why is he so direct about pronunciation but vague about the fucking future of humanity?

Also, despite the fact that the film specifically tells us that Bodhi communicates telepathically, the Solarbabies all talk to him out loud. They know they don’t have to, but they do anyway. Why?

Well, of course, it would look pretty silly if the Solarbabies just sat around having staring contests with the magical space ball while the audience wonders what they fuck they’re silently communicating, sure. But then why introduce the concept of telepathy at all? If everyone is still going to speak verbally, why point out that they never have to?

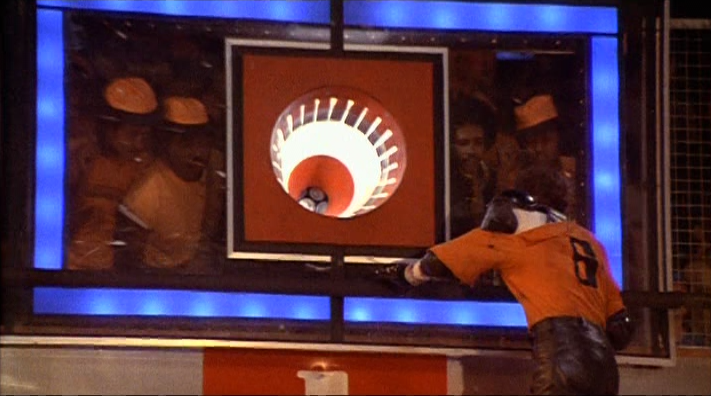

At one point, the Solarbabies all play Skateball with Bodhi.

As in, Bodhi is the ball. They lob him around and catch him and stuff, and I guess that’s fine. It’s possible Bodhi is communicating silently to them that he likes it. It’s equally possible that he’s tearfully pleading with them to stop.

We’ll never know. The marvels of telepathy.

Then one Solarbaby pitches Bodhi at another Solarbaby, who fucking smashes it with his lacrosse stick.

Bodhi explodes into a shatter of glimmering stardust or whatever, and the music is triumphant and the kids all gasp in awe, but this is a living thing! How the hell did the Solarbaby know he wouldn’t just kill Bodhi? Or at least give him a concussion? It’s a creature they know nothing about. Why in shit’s name did they think it was okay to club him like a fucking baseball?

What if it did kill Bodhi? What if the magical space ball from beyond the stars came to Earth to rescue humanity, just to get trapped in a cave for God knows how long and then dug up by a bunch of kids who bludgeon it to death? Great fucking movie.

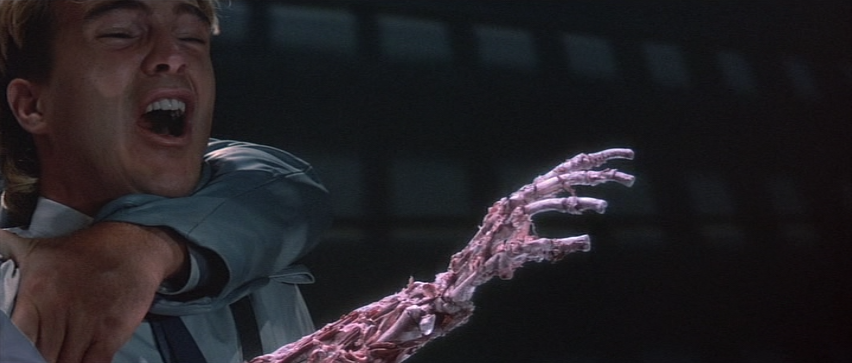

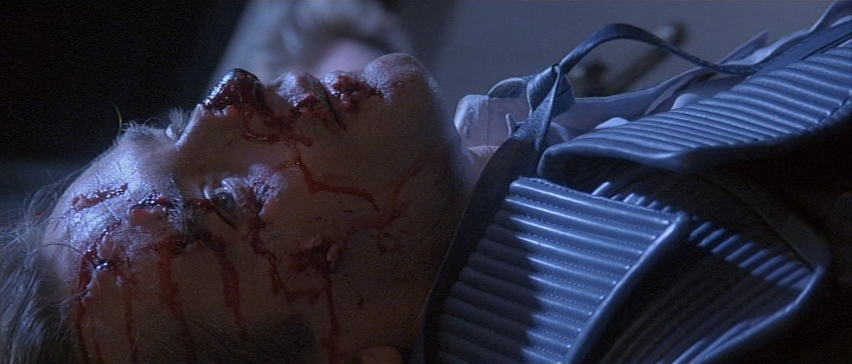

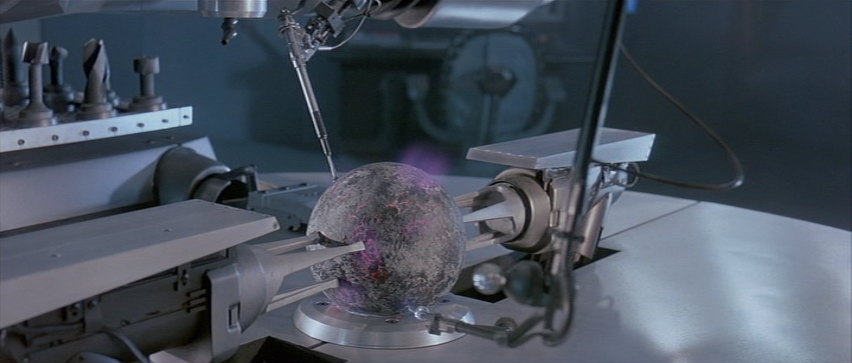

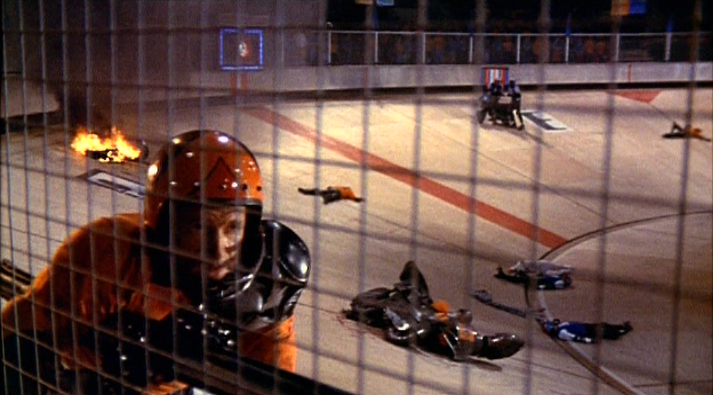

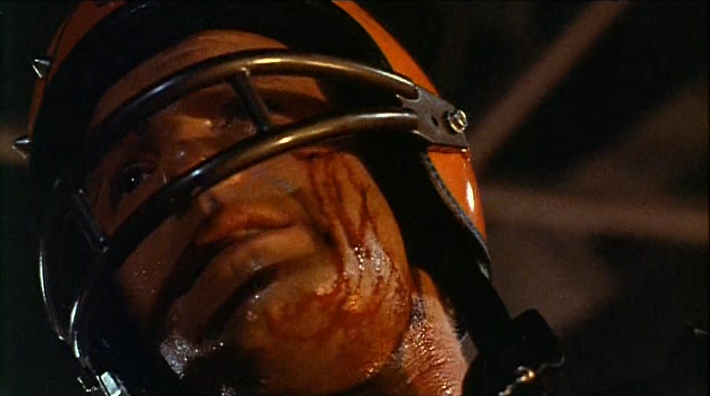

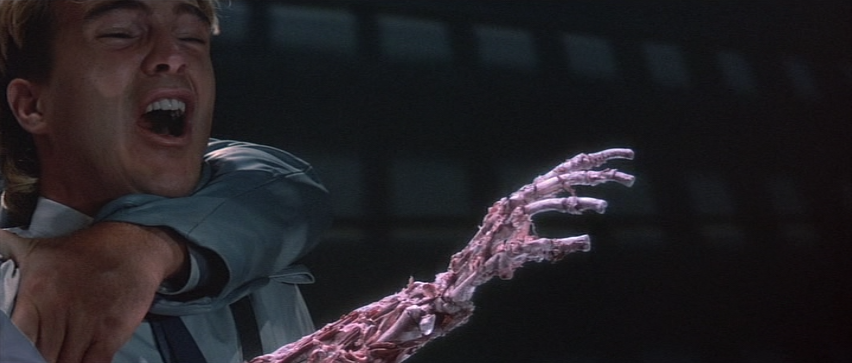

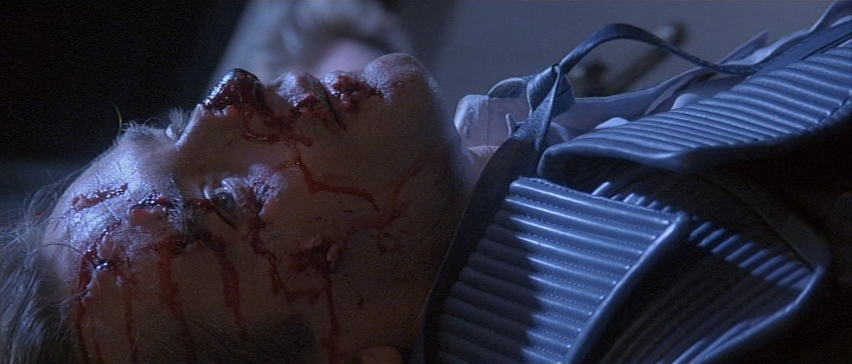

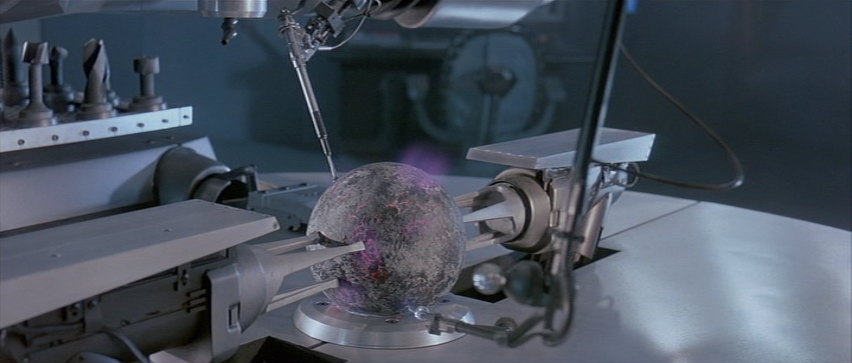

Then, toward the end, the cartoon Nazis and some woman who dresses like Grace Jones get their hands on Bodhi, and they try to destroy it by cooking it and drilling through it.

And I guess it’s nice that they already had a Bodhi-killing machine all rigged up and ready to go, just in case a Bodhi ever showed up, but the weird thing is that while they do this shit to him, we hear Bodhi screaming in agony.

So much for telepathy, huh, pal?

The Solarbabies, of course, show up and rescue Bodhi, which involves much bloodshed and the murders of anonymous henchmen.

There’s an extraordinarily tense moment when one of the kids skates real good so he’s able to vault an electrified fence. He opens the gate for everyone, but because this is a movie it has to automatically close and everyone is worried the not-deaf kid won’t skate real good. But thankfully he skates real good after all.

So they save Bodhi and…he’s fine. In fact, minutes after he was roasted and drilled, he’s ready to restore all the world’s water. Dude doesn’t even need to rest.

So what was all that screaming about, Bodhi?

Was he just…faking it, or something? I guess the people in the audience needed to worry that Bodhi was in actual danger — nothing keeps an audience on the edge of their seats like to possibility of a glowing ball getting broken or something — but within the movie, why was he crying out in pain if he was actually fine?

I’m skipping over large chunks of the movie that make no sense so that I can discuss other chunks of the movie that make less sense. It’s really pretty fantastic.

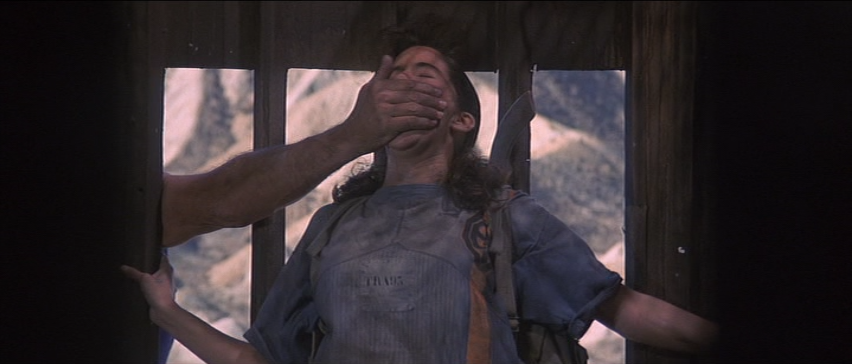

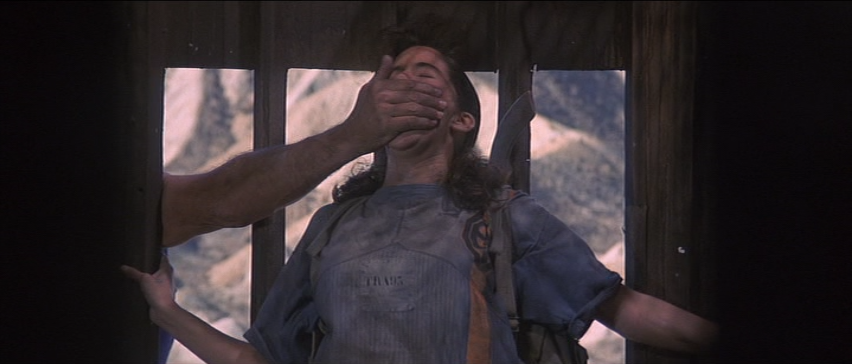

There’s one scene in which the girl Solarbaby gets separated from the others in a settlement, and we see a hand grab her from behind and cover her mouth. She’s being kidnapped! Oh no! Who could her rapist be this time?!

But, no, it actually turns out that it’s either her father or someone her father sent to bring her home. She’s totally fine and “home” is actually full of comfort and safety and fresh water. What’s more, her dad looks like a kind of Disco Christ. Can’t really complain about anything!

So why did the person taking her home do it in this ridiculously scary way? I understand walking up to someone and saying, “I know your dad; follow me and I’ll take you to him,” can sound pretty shady. But grabbing a woman from behind and muffling her screams is in no way a more comforting approach.

Anyway, the Solarbabies find her and get a tour of her home and the first thing one of them does is jump into a body of water and start stomping around and kicking it at people. What if that was their fucking drinking water, you little shit? What if that was the only water in town? You don’t know squat about this place. Get out of the fucking water!

Solarbabies isn’t all bad, but with one exception I can’t give it specific credit for anything it does right.

The best part of the film is something innately good about any post-apocalyptic media: the chance to see how different settlements have adapted to life in the wasteland.

The settlement with water is safe and happy because they stay deliberately hidden. Tire Town is a labor center that survives by commerce (and, to some extent at least, prostitution). The Orphanage is well stocked but also fortified and has the specific goal of programming youngsters to support The Protectorate. (And the secondary goal of teaching them to skate real good.)

There’s also a Tchigani town that echoes early Native American settlements, bringing society (assuming this takes place in America) full circle. The best part, though, is that the wise elder in this settlement lives in what used to be an amusement park’s haunted house. It’s full of creepy things like skulls and spiderwebs and torture devices, which does a great job of setting the mood both he and the film are going for, and which are fabrications from a more frivolous time, from when symbols of death and misery were a kind of dark entertainment rather than a daily reality.

It’s…actually a fairly intelligent detail. And it’s the only one.

I guess the movie also gets a point for featuring a theme song by Smokey Robinson. Not that it’s good or even marginally listenable, but it’s amusing to me that a genuine legend will now always have something called “Love Will Set You Free (Theme from Solarbabies)” stuck like a stubborn kidney stone in his discography.

With no real purpose to anything that happened, no room for investment in any of these characters, and no clear concept of why the movie was made, it probably shouldn’t be surprising to say that the ending fails to redeem it.

In fact, Solarbabies doesn’t end so much as it just stops happening.

Bodhi fixes the world because if he doesn’t do it now humanity will be cursed with a sequel, and we see that the oceans are back in a sequence deemed insignificant enough that it plays out silently behind the credits.

Further emphasizing the fact that nobody involved in this movie ever met a human being, the Solarbabies run along the beach in their socks. Fucking ew, Solarbabies.

And that’s Solarbabies. The one movie this year in which the central game was never intended to be one of life or death, though the characters sure as hell turn it into one, chuckling all the while over the memories they’re creating together of turning adults they don’t like into burnt skeletons.

Director Alan Johnson died in July of this year, which I didn’t realize until I was doing some research for this review. He’s better known as a choreographer, and Solarbabies was one of only two films he directed. He worked closely with Mel Brooks on a number of movies, and Solarbabies was actually produced by Brooksfilms.

Solarbabies is not a great film, but it’s a great terrible film. If you like to laugh at movies that fail to function on any conceivable level, definitely check this one out. Trust me, I didn’t spoil all the surprises; I barely scratched the surface.

Interestingly, in this year’s batch of films, it’s the most life-affirming one that behaves flippantly toward death.

Whether it was the murder of innocents for which Ben Richards was framed in The Running Man, the failures of Spumoni and Mama Pappalardo to survive their challenges in Deathrow Gameshow, or the braindeath of Moonpie in Rollerball, deaths in these films had consequences that others would have to live with, react to, and move on from.

Solarbabies doesn’t dwell on its many, many deaths, and as such it’s actually the film that treats its deaths most disrespectfully. The one character that is mourned in any capacity is the owl. The owl is collateral damage in a battle between two human factions nobody, least of all the audience, cares about.

The owl mattered to one of the characters, so the other characters bury it and sit in silence for a moment.

It’s almost as though Solarbabies is rubbing it in, what little value human life has in this post-apocalyptic hellscape, when an owl is entitled to a funeral and a stack of charred remains sees teenagers skipping away and giggling.

Almost. Because Solarbabies isn’t smart enough to have any idea of what it’s actually saying.

Any accidental breakthroughs are collateral damage in this mess of conflicting ideas nobody should ever want to see.

So, y’know, be sure to check it out.

And have a happy Halloween.