Two years ago (because time does, indeed, fly) I put together A Wes Anderson Primer as a short resource for those who might be interested in Moonrise Kingdom, or weren’t sure if they’d be interested, because they hadn’t really seen much Anderson yet.

This time around, I’m Primer-ing you on Thomas Pynchon…my favorite author. Inherent Vice comes out in December…the film, that is. The first film he’s ever allowed to be adapted from his writings. Perhaps you’ve seen the trailer. Perhaps you haven’t. Either way, if you’re not already a fan of Pynchon’s, the odds are good that you don’t know what the hubbub is about.

Sure, it looks like a cool, funny movie. But why is it important?

You won’t know — or won’t understand, anyway — unless you read some Pynchon for yourself. That’s an intimidating task, though. Pynchon’s a notoriously and deliberately opaque figure, and while I wholeheartedly feel there’s something in his books for everyone, finding that something can be impossible if you go in unprepared. I’m not exaggerating; I adore the guy, and I still find his books frightening.

But let’s go through each one of them in turn. I’m going to try to help you find a way in. And don’t forget that you can win any one of these books by taking the Noiseless Chatter reader’s survey.

V. (1963)

Length: 507 pages

Length: 507 pages

Overview: Dual protagonists Benny Profane and Herbert Stencil more or less alternate their respective searches for meaning. Benny is described in the novel as an incurable schlemiel, swept along by the forces — and inanimate objects — of the world around him, while Stencil is the opposite and actively seeks an answer to a question he may not fully understand: the identity of a person (or place…or thing…) known to him only as V. Woven throughout their stories are the stories of others, relayed both first-hand and via flashback, painting a larger portrait of a world of isolates, each seeking some kind of reason to carry on. V. is packed with great characters (some of whom we’ll get to know better in later novels), sharp satire, and haunting imagery, but it’s not nearly as tight as Pynchon’s later works. While a chatty aimlessness is one of Pynchon’s greatest tools — and while it absolutely is a theme explored through the lenses of our main characters here — V. feels a lot like it’s padding for time, and the reader doesn’t always return from these bizarre sojourns with the feeling of there having been a purpose to what he was just told. In Gravity’s Rainbow especially Pynchon manages to retain — indeed, amp up — the disorientation, but it always feels purposeful. Here, excellent though the writing is, it often feels like we’re watching a great artist find his footing. The strongest moments in the book are the ones that see the characters identifying a goal for themselves and working toward it, whether that’s the extinction of alligators in the New York City sewer system, the disassembly of a priest, the attempted theft of The Birth of Venus, the cosmetic reconfiguration of a lover’s face, or the quest of father-and-son adventurers to return to a place that may never have existed. Each of these goals — and dozens more — seem to provide as much of a spark for the author as they do for the characters involved, and it’s here that we catch glimpses of the Thomas Pynchon we know today.

Opening Timeframe: 1955

Chronological Sequence: Fourth

Pynchonverse: As Pynchon’s first novel and almost everybody’s introduction to his talents, the entirety of V. can be seen as a framework for what’s to come. The alternating comedy / horror, the meandering expeditions through history, the extreme violence and sexuality, visions of unreachable utopia, a detective figure, the withheld climax, the winking original songs…in fact, one would be hard-pressed to find a single hallmark of Pynchon’s that isn’t on display already here, however rough some of them might be around the edges. Also, being his first novel, there aren’t any real callbacks here. As you’ll see, however, every release that follows takes the opportunity to weave itself into a much larger, even more satisfying framework.

The Crying of Lot 49 (1966)

Length: 183 pages

Length: 183 pages

Overview: Oedipa Maas receives news that not only has her absurdly rich ex-lover passed away, but that he’s appointed her executor (or executrix, she supposes) of his estate. With the help of a former child actor turned attorney, Oedipa disentangles the affairs of the late Pierce Inverarity, and finds an entirely new kind of tangle emerging instead. It involves a (possibly fictional) centuries-old feud between rival postal services, echoes of which seem to be in evidence everywhere she turns. Rare stamps, Jacobean revenge dramas, and even otherwise innocuous children’s songs convince her that either some incredible secret is just waiting to be uncovered, or she’s gone genuinely insane. It’s a hilarious book that pivots into psychological horror on a dime, and is constantly weaving at least two types of tales into the narrative at once. Pynchon himself seemed dismissive of it in his introduction to Slow Learner, but it’s one that I come back to frequently. Admittedly, its brevity is a good reason for that. (Reading the entire book in one day, which I’ve done several times, reveals a whole other level of interconnections, and I recommend doing that at least once.) That brevity, however, doesn’t make it much “easier” than anything else Pynchon has written. In fact, my first memory of The Crying of Lot 49 is a fellow student breaking down in one of my college literature classes because he was supposed to give a presentation on it and, despite reading it multiple times, had no understanding of the book at all. I bought it soon afterward because I was intrigued by the idea of such a slim volume putting up a fight like that. And, sure enough, it took a good long while before I was even barely comfortable talking about it either. Its ending is very instructive to readers of any Pynchon; it feels as though it’s unresolved, and in terms of the book’s central mystery, it is. But while you (and Oedipa) were following one kind of plot, Pynchon was actually developing another. You’ll get to the end looking for an answer, and at the end you’ll get an answer. But the odds are good that you and Pynchon had very different questions in mind, and the fact that such a rich and satisfying experiment in misdirection comes from a seemingly tiny, silly, unassuming text is endlessly impressive to me.

Opening Timeframe: 1964

Chronological Sequence: Fifth

Pynchonverse: Ballistics company Yoyodyne appeared in V., along with Clayton “Bloody” Chiclitz, who himself appears here and again in Gravity’s Rainbow.

Gravity’s Rainbow (1973)

Length: 760 pages

Length: 760 pages

Overview: Man…an overview of Gravity’s Rainbow. A more daunting exercise does not exist. Period. It’s my favorite novel, as you probably know, but it’s also one that I wouldn’t wish on my worst enemy. I remember the first time I read it: I hated it. It was painful to read. At almost no point did I feel as though I had a handle on what was happening, and when I did it didn’t last long. But I pushed through it, and I’m glad I did, because when I revisited it a few years later, it went much better. I was able to pay more attention to certain characters because I knew they would pop up later in the narrative, even if it happened after hundreds of pages had passed. I knew to treat other characters (and passages) as less-important digressions because they didn’t actively factor into anything to come, which freed me up to enjoy them (if not always comprehend them). Gravity’s Rainbow is a book that needs to be re-read, not read, which makes it a serious time commitment, and by no means a good recommendation for the Py-curious. In fact, I may have only been able to make sense of it due to a very superficial guide I found online…one that didn’t seek to interpret the book for me (because fuck that…if I want someone else to do the interpreting why am I reading in the first place?) but one that simply outlined in a sentence what happened in each section. That allowed me to know which scenes were flashbacks, fantasies, hallucinations, monologues delivered by characters who are dead (which the book may or may not make clear before you meet them), and so on. Gravity’s Rainbow is an almost endless exercise in self-orientation, and it’s a breathtakingly beautiful one. The beauty, however, lies beneath a thick layer of frustration. If you are dedicated enough to dig through to it, you’ll be glad you did. If you’re not, and only make it partway through the barricade, you’ll regret that you tried in the first place. Whew. There’s my overview of Gravity’s Rainbow. Unless you want to know something about the plot, which is a sort of loose mosaic of scenes and horrors interlocking their way across the insanity of World War II. The nearest thing to a protagonist we have is Tyrone Slothrop, an American serving in England during the V-2 blitz on London. Slothrop gets roped into a conspiracy — only gradually realizing he’s the central component — when it’s observed that the sites of his professed sexual conquests turn out to be the exact targets of rocket attacks a few days later, without fail. Slothrop is interrogated and studied for any information he might have — consciously or not — about the connection, a process that takes him from being plied with alcohol and sex to being abandoned in “the Zone” without money, identification, or a way home. But Slothrop’s story is only one of many, and it may not even turn out to be the most important to you as a reader. Which is why Gravity’s Rainbow is impossible to summarize; it’s a book that exists in your mind after you read it, not one that exists as words on a page. It’s a work of brutal, repulsive, challenging, brilliant, fearless, unforgettable art. It’s one you should both experience at some point in your life, and avoid at all costs.

Opening Timeframe: 1944

Chronological Sequence: Third

Pynchonverse: This novel reunites us with several of the minor characters we met in V., including Pig Bodine, “Bloody” Chiclitz, Kurt Mondaugen, and Weissmann, all of whom have more important (if not necessarily larger) roles here. Pappy Hod from that same novel also gets a small mention.

Slow Learner (1984)

Length: 208 pages

Length: 208 pages

Overview: A collection of Pynchon’s early short stories, Slow Learner lives up to its self-effacing title. As flawed as I consider V., I absolutely grant that it provides marvelous indication of the talent to come. The stories that comprise Slow Learner, though, won’t seem much different in terms of quality, style, or substance from anything you might have seen from classmates in a college-level writing workshop. That’s not to say they’re bad, but they don’t strike the reader as the work of somebody that was in command of his abilities. (And, in objective fairness, subsequent writings have proven that he certainly was not.) What makes this book worth owning, though, is the introduction, penned by Pynchon himself. If you think I’m hard on these stories, you should read what he has to say about them. The introduction is an older, wiser, respected Pynchon, looking back at the floundering youth who wrote these stories and seeing a different person entirely. It’s a brief memoir, personal reflection, writing instruction, and advice column all in one, and for a man that communicates with the outside world so rarely in any form, the introduction is beyond value. It’s also worth noting that the only editions of this book I’ve ever seen (including the first edition), contain five stories. However a sixth story, “Mortality and Mercy in Vienna,” was apparently included in at least one printing, somewhere, at some point. I’ve yet to confirm this myself, but if I don’t mention it somebody else will. (And if anyone knows which edition(s) contain(s) this story, please do let me know.)

Opening Timeframe: n/a

Chronological Sequence: n/a

Pynchonverse: A reworked version of the story “Under the Rose” eventually became a chapter in Pynchon’s debut novel, V. That novel also features Pig Bodine, who appears in the story “Low-lands” here, as well as in Gravity’s Rainbow. Hogan Slothrop, Jr., from “The Secret Integration” is the nephew of Tyrone Slothrop, the closest thing we get to a hero in Gravity’s Rainbow.

Vineland (1990)

Length: 385 pages

Length: 385 pages

Overview: In the almost twenty years that passed between this and Gravity’s Rainbow, expectations soared. Whatever was taking Pynchon this long to deliver his next sermon, it was bound to be worth the wait. And then, like a wet thud, Vineland hit shelves, disappointing idiots everywhere. Vineland is one of my favorite Pynchon novels, and probably the one I recommend most often to readers looking to experience him for the first time. And, frankly, the “It’s not what I wanted it to be” backlash that the book received is insulting. Yes, it was Pynchon’s easiest novel to date, but that doesn’t mean it’s of a lower quality. With Vineland, Pynchon’s sharp social criticisms are as biting as ever; the fact that they’re couched in some of his most overtly comic (and comically effective) writing yet should have been a cause for celebration…but I’m digressing. The story takes place with an Orwellian hat-tip in 1984, where unemployed ex-hippie Zoyd Wheeler finds his life of quiet dreaminess shattered by the re-emergence — in a way — of his ex-wife, Frenesi…as well as her old suitor, government man Brock Vond. In order to keep his daughter Prairie safe from the fallout, he sets her out on an adventure of her own, and the bulk of the novel drifts backward through time as we and Prairie weave together — via newsreels, newspapers, hearsay — an understanding of exactly who her mother was, and of everything America lost, destroyed, and gambled away between the mid 60s and the mid 80s. It’s a great book with warmth found in the most unexpected places, such as between Zoyd and his police department counterpart Hector Zuniga (which, in retrospect, plays like a dry run for the relationship between Doc and Bigfoot in Inherent Vice), or the one which develops between a hired assassin and the diminutive Japanese man she accidentally kills. (It makes more sense when you read it, I promise.) Pynchon is as insightful as ever, if not necessarily as deep, and this relatively surface-level approach allows him, I feel, to explore the outer sadnesses and flashes of desperation as impressively as he’s explored the internal emptiness and quiet panic of his characters in the past. Vineland is a lush and memorable narrative, with some of his best-defined characters and most impressively catchy songs. Its ending, as well, stood as the final chronological sequence in any of his novels before the release of Bleeding Edge, and it serves as such perfect punctuation that I kind of wish it still was.

Opening Timeframe: 1984

Chronological Sequence: Seventh

Pynchonverse: Mucho Maas from The Crying of Lot 49 appears here, providing just a little bit of a clue — but still no answer — as to what happened after the end of that novel.

Mason & Dixon (1997)

Length: 773 pages

Length: 773 pages

Overview: Astronomer Charles Mason and surveyor Jeremiah Dixon carve their famous line into a young America, an action itself that seems to draw a line between generations of hopeful superstition and the colder, more measurable Age of Reason. It’s also Pynchon’s most difficult text, which is saying something. The entire thing is written in, for lack of a better term, mid-Colonial American. What that means for you as a reader is that the words on the page — in sentences, in paragraphs — don’t necessarily behave by the rules you seek to impose upon them. Long-forgotten slang and obsolete terminology abound, meaning that everything you read gets read twice: first to find out what’s written on the page, and second to translate it internally into something you can understand. As a result, Mason & Dixon is both tiring and off-putting…at first. Much like Gravity’s Rainbow, this is a book that necessitates multiple readings. You cannot read it once; that’s a waste of time for everybody. You should commit either to reading it twice, or not at all. The second time, at least, you’ll understand what’s happening, as you’ll be in tune with the textual approach. And every time beyond that, you’ll fall in love a little bit more. The relationship that blooms between our dual protagonists is one of the richest in Pynchon’s arsenal, and there’s an amazingly touching undercurrent of record and measurement beating back, and eventually supplanting, legend itself. The world of Mason & Dixon seems to grow along with its characters, itself adapting to technological advancements and provable science. This means that legends — whether talking dogs, giant worms, hollow Earths, glowing Indians, or golems — do exist…until they’re disproven, anyway, at which point they never existed, and they shift permanently into the realm of fancy. It’s a neat trick, and Pynchon handles it beautifully, turning the dawn of the Age of Reason into a kind of unspoken tragedy as much as it is an advancement, and forging strong bonds between all those who witnessed it together. It’s an absolutely beautiful experiment, which might stumble and fall along the way, but which ultimately brings us the most rawly emotional moments to leave Pynchon’s pen, including Dixon standing up to a slaver, and Mason confronting the ghost of his deceased wife. When I first read this book, I was disappointed. I think I expected it to be funnier. The joke, I’m pleased to admit, was on me.

Opening Timeframe: 1786

Chronological Sequence: First

Pynchonverse: The Reverend Wicks Cherrycoke shares a last name with a character in Gravity’s Rainbow, and Fenderbelly Bodine is the earliest known ancestor of the Bodines we meet (and have met) in V., Gravity’s Rainbow, Slow Learner, and Against the Day.

Against the Day (2006)

Length: 1,085 pages

Length: 1,085 pages

Overview: The lives of several major character sets are traced from the World’s Fair in Chicago all the way through — and past — The Great War. I’ve read Against the Day several times, but have rarely finished it. It’s in competition with V. for being my least favorite novel of Pynchon’s…and yet, there’s so much good in it that I find myself thinking about it, meditating on it, wishing to revisit it. I think the problem with Against the Day is that there’s simply too much going on. Unlike Gravity’s Rainbow, which utilized “too much” as a successful method of piecing together a global nightmare, Against the Day wants to be both human and cosmic at once, which means we find it doing great things that feel incompatible with the other great things it does. It’s a fractured experience, but one worth having at least once. While I’m fully aware that I fall into Pynchon’s trap when I read the first few chapters of the novel and get amped up for an exciting saga of Western revenge, the fact is that the stories that follow are, on the whole, not quite as interesting. Overlong passages and seemingly meaningless sequences of events in which characters are shuffled all over the world for the sake of shuffling them make this feel like Pynchon at his least focused and most frustrating. That’s not to say it’s without its merits: an extended sequence in which an arctic expedition finds a malicious figure buried in the ice leads to some of Pynchon’s most chilling writing yet, and the various uses / implications of the double-refracting mineral known as Iceland Spar lead to moments of both effective comedy and tantalizing philosophy. It also introduces us to Dally Rideout, my favorite female character in any of Pynchon’s books, and a firm candidate for favorite overall. (Merle Rideout probably wins the award for Best Pynchon Dad as well…and it probably says something that he’s not actually related to Dally.) Frank Traverse, the universal runner-up, also has a particularly affecting character arc. In short, Against the Day would have been better had Pynchon dedicated more focus to almost any of his ideas. As it stands, too much adds up to too little.

Opening Timeframe: 1893

Chronological Sequence: Second

Pynchonverse: We witness the birth of Jesse Traverse, grandfather of Frenesi Gates in Vineland. We also tag along for a first-hand exploration of the “hollow Earth,” a theory floated in Mason & Dixon. This book features O.I.C. Bodine, a relatively minor — but still welcome — link in the Bodine lineage. The skyship Inconvenience shares a name with a more traditional ship in Mason & Dixon. We also check back in with La Jarretière (Melanie l’Heuremaudit’s stage name in V.) to find that Pynchon revised — perhaps for reasons known only to him — her grisly ending from that book.

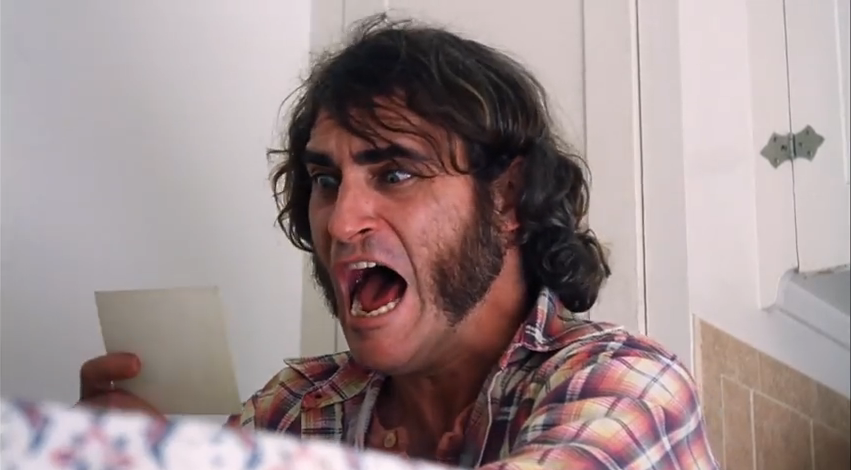

Inherent Vice (2009)

Length: 369 pages

Length: 369 pages

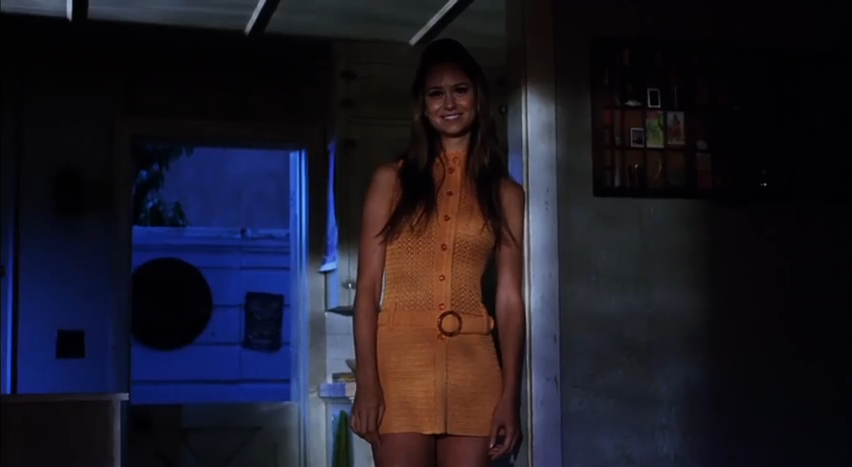

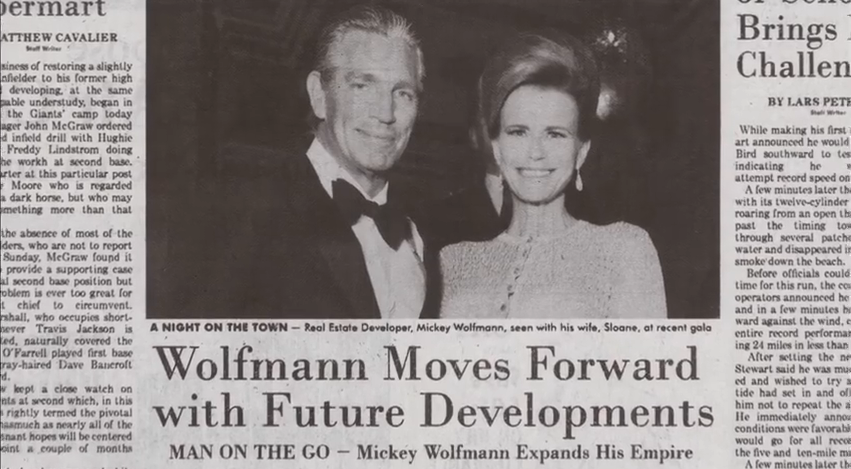

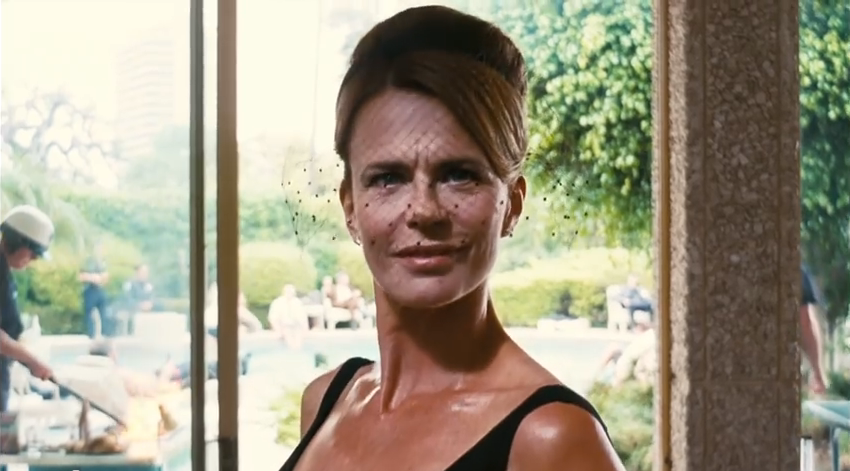

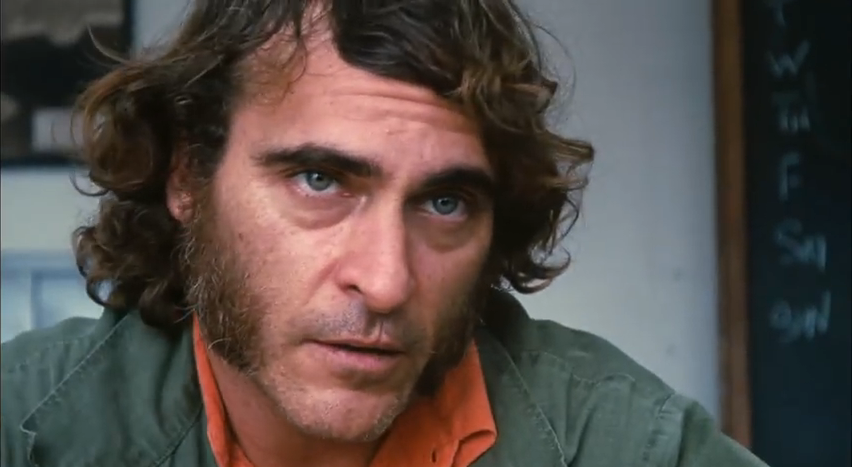

Overview: With the exception of Mason & Dixon, I think each of Pynchon’s novels features a detective figure in a major role. Inherent Vice is the only one, though, that features an actual detective as its protagonist. Doc Sportello is that protagonist, a smarter-than-he-looks hippie being washed unhappily into the 70s, while the Charles Manson trial unfolding in the background serves as a sad reminder that 60s idealism is gone for good. The case he’s working on is one he isn’t even getting paid for: his ex-girlfriend informs him of a plot to kidnap her real-estate mogul beau, Mickey Wolfmann. This being Pynchon, of course, a dozen other stories get woven into and spun out of what should be a relatively straight-forward investigation, and I don’t think I’m spoiling anything by saying that making it to the end of the book doesn’t necessarily imply that you’ll find any kind of resolution. At least, not that resolution. The fog-heavy coda plays like a sustained chord. Some eternal, melancholy echo that hangs in the air long after you’ve placed Inherent Vice back on the shelf, and part of me wishes that scene — that moment — could stand as the last thing Pynchon ever gave us. But, whoops, I’ve gone and skipped over the whole novel. That might be because the best things about Inherent Vice are the exchanges, the way the characters interact and intersect. This is probably Pynchon’s most realistic novel, in that regard, as every friendship and every antagonism feels natural. These are people who both need and needle each other, and are trying, in their own ways, to find meaning in the significant cultural shift happening around them. Most of them find nothing, but none of them stop searching. And every so often Pynchon gives these poor folks a break. The announcement of a pregnancy. A grudging admission of respect. An unexpected payout from a forgotten casino. Throughout Inherent Vice things go from bad to worse, but not at a steady clip. There are moments of respite. There are chances to catch your breath. And there are opportunities to be thankful for what you have, even though — or perhaps because — you know you can’t have it forever.

Opening Timeframe: 1970

Chronological Sequence: Sixth

Pynchonverse: Doc is the cousin of Scott Oof, a young musician we met in Vineland. He’s also done some work for Sledge Poteet, another character from that book. What’s more, we visit Kahuna Airlines here, which played a big role in Vineland, and the two novels also share a fictional location (Gordita Beach). At one point in the book we get a mild hallucination in which Doc has a conversation with Thomas Jefferson, whose dialogue reprises the textual stylization of Mason & Dixon.

Bleeding Edge (2013)

Length: 477 pages

Length: 477 pages

Overview: Maxine Tarnow, a decertified fraud investigator, finds herself set by various interested parties on long, complicated, dangerous trail, similar to the one on which Doc found himself in Inherent Vice, but here the backdrop is entirely different. Technology allows freer and faster access to information, but it brings with it the “Deep Web,” which might not be an inherently bad thing but certainly provides a platform for the bad to grow worse. This symmetrical advancement, both positive and negative in roughly equal measures, serves as a big theme; technology allows us to spread word of injustice, but it also makes it easier for professional silencers to track us down. It’s a terrifying, all-too-recognizable landscape that he paints, and yet it feels like Pynchon’s most personal novel to date. Sure, he’s not a female detective, but there’s an unexpected warmth and openness in what drives Maxine, in how she interprets the world, and in what she allows to break down her barriers. I’ve warmed up to it quite a bit since I reviewed it, and though I do still recognize its flaws, I’ve come to be disarmed by just how fragile he allowed this small sliver of his world to remain. When the towers come down in September — as we know they must — the things that matter to these people will get reprioritized, which itself is both a positive and negative advancement. The good times (and good people) will be gone, but the bad times begin to heal in the wake of larger tragedy. Lives lost on the surface continue to exist in echoes of technology. Fears and frustrations are borne out in video game behavior and a child’s choice of Halloween costume. Maxine’s lesson is daunting in its complexity, as she’s punished (along with everyone else) for both caring too much and not caring enough. Incorporating such a relatively recent event into one of his narratives was a gamble — especially 9/11, considering how often it’s been used for the sake of cheap manipulation — but it leaves the modern-day reader with an innate understanding of what Maxine feels at the end of the novel, which resolves with perhaps the most poignant, affecting, simple image Pynchon will ever create.

Opening Timeframe: 2001

Chronological Sequence: Eighth

Pynchonverse: Misha and Grisha, a pair of Russian revolutionaries from Against the Day are reborn here in an updated (and arguably more threatening) context. There’s also a reprise of “Soul Gidget,” a Pynchon song we learned the lyrics to in Inherent Vice.