“Expenses” may be the bleakest episode of Better Call Saul yet, which makes it a worthwhile point of comparison with Breaking Bad. See, that show was pretty bleak as well. On the whole, I’d say the agreed-upon bleakest episode is “Ozymandias,” and I’d have a difficult time putting forth any other forerunner.

But what made “Ozymandias” bleak?

Well, there were the deaths of major characters: Hank and Gomez. There was the kidnapping of our second lead, Jesse, as a result of our actual lead selling him out. There was the sudden empowerment of the show’s villains, who then seized the money Walt hid in the desert…the money that was, indeed, the root of all of Walt’s evil. There was the clear and unavoidable distinction between the desperate Walt who opened the series and the cruel, mindlessly vindictive Walt we had now. There was sharp betrayal with fatal consequence that left families irreparably broken.

It was bleak. And even if you’d finger a different episode as your particular “bleakest,” your reasons would probably be similar to everything I said above. The specifics would change, but the broad strokes would not. Breaking Bad had a kind of bleakness that lent itself to being explored in primarily those ways.

And now we have Better Call Saul‘s equivalent.

With no death.

With no betrayal.

With no shifts in power.

With no beloved characters in danger.

Better Call Saul lives in the shadow of Breaking Bad, and God knows its marketing team is comfortable with it remaining there for the rest of time. But the contrast between the way the two shows explore rock bottom — and what they each consider to be rock bottom — is an important and instructive one. It’s where we find each show’s soul. It’s where we see illustrated most clearly the difference between right and wrong. And, in each case, it’s illustrated by the characters choosing incorrectly.

We find Better Call Saul plumbing its own depths in a quiet episode that, ironically, covers a lot of ground without digging deeply into any of it. “Expenses” is decidedly superficial, sketching out the vague points of a tragedy and letting its own silence — and ours — fill the space in between.

The result is…bleak.

And it’s a bleakness that actually works very well with my recurring concern about the show…while asking me to reconsider it.

See, I want Better Call Saul to stand on its own merits. It will necessarily provide backstory for characters we knew in Breaking Bad, and I’m more than happy for the old familiar faces to pop up now and again, but I’ve wanted Jimmy McGill’s story to be…well…a story. Not a preamble, not a prelude, not the long-lost Book One. I want Better Call Saul to be one thing, and Breaking Bad to be a related but distinct other.

And yet, that might be unfair. I don’t know that Better Call Saul ever was promised to us in that way. Maybe Better Call Saul is exactly what it seems like it would be: not the story of Jimmy McGill, but the story of how Jimmy McGill became Saul Goodman.

I wanted the former, and for a good while I thought that that’s what I’d get, but if the show is really about the latter…if it’s less about transformation than it is about that one particular transformation…then, well, I can’t complain.

And “Expenses” suggests that Better Call Saul is something other than what I’d hoped it would be. Fortunately, it also suggests that that’s not a bad thing.

“Expenses” functions as it does — as bleakly as it does — entirely because we already know Breaking Bad. Seeing these characters hit the floor is only as effective as it is because we know what’s to come. We know that while it’s not the end of their story, it may be the end of their relatively safe times. We know that as each of these characters is faced with a chance to extract him or herself from what is clearly a bad situation, they won’t.

The episode doesn’t end by telling us they won’t, because it doesn’t have to. The episode knows that we already know.

And so the bleakness of “Expenses.” A question is raised, but it’s not the deliberation we focus on. It’s the impending doom on the horizon. The knowledge that however many episodes may pass before decisions are made official, the characters are already doomed.

I wasn’t exaggerating up there, either; each of these characters does face a chance to extract themselves. Here. In this one episode. All of them independently of everyone else. What’s more, it’s handled so effortlessly that you may not even recognize the fact that they’re all facing the exact same decision at the exact same time. It’s good writing, as it nearly always is, and it’s so natural as to be invisible.

The most obvious example might (might) be Kim, who snaps rudely during a meeting with her client. She takes it back — and all seems fine — but then blurts her regret about piling on Chuck the way she did. She’s openly having second thoughts, and Rhea Seehorn put forth some of the best physical acting I’ve ever seen on television in that scene. Her voice remains steady, but the inner turmoil is conveyed through her breathing. If you’ve ever seen somebody pop in real life and then stuff it right back down, you’ll know what to look for. And you’ll find it right there.

Then there’s Mike, who keeps good on his unwitting promise to build a new playground for the church. While there he bonds with another parishioner, and we see a side of him we’ve never seen before, on either show: Mike with a real friend.

Prior to this, I think the closest friend we’ve ever known him to have was Jesse Pinkman, and that relationship — as important and genuine as it was — also involved a clear and necessary distance. Here he lets her help pour concrete, and later listens intently to her story of her missing husband. He opens himself up to her — and to the church — in an unexpectedly warm way. He lets his guard down. He accepts help. He accepts…others.

It’s a different Mike. It’s a Mike he might even like being.

But it’s not the Mike we lose in Breaking Bad. We know he pushes it away.

Then there’s our old cobbler-sitting, card-collecting friend Pryce, who finds himself seduced back into the game by the promise of $20,000 for easy work. Mike specifically cautions him against getting involved. In fact, he tells him not to and instructs him to come up with an excuse. This is Pryce’s chance to break free as well as a reminder that he’s lucky to have made it out alive the first time. Needless to say, he doesn’t listen, either.

And that’s not all. There’s Nacho, whose plot against Hector has holes poked in it, and who is also cautioned against proceeding. We can say with confidence that — while he may or may not succeed — he certainly won’t put the breaks on.

Centrally, though, there’s Jimmy, whose conclusion is the most foregone.

This is his chance to extract himself, too. To admit defeat. To swallow the loss on his airtime and malpractice insurance, to knock out his community service, and to find a job that brings in more money than he spends.

But he doesn’t do any of that. He sinks more time and money into his commercial gambit, and lies about its actual performance to Kim. (Several times over.) He uses his failed appeal to his insurance agent as an opportunity to kick Chuck even harder while he’s down. He digs his heels into a venture that isn’t — in any sense of the word — working, refusing to find another professional and ethical direction for himself even when, it has to be said, that would be the much easier option right now.

Every one of those characters has a chance to take a deep breath, think about where they are, and take a step toward getting, instead, where they’d like to be.

But they each grit their teeth and decide against their own better judgment to stay where they are. Each of them is a failure raging against an opportunity to succeed.

And that’s pretty remarkable characterization to pull off five times in succession in a single episode.

I’m interested in the Jimmy we see in “Expenses,” because I think we’re about halfway toward him truly becoming Saul. Certainly there’s a balance between his two incarnations here, and we can feel it teetering.

He still has a heart, and is still a largely decent human being, refusing to take money back from one of his film crew, even when he clearly needs it. Yet he schemes to get Chuck’s insurance rates raised with a cruel crybaby act.

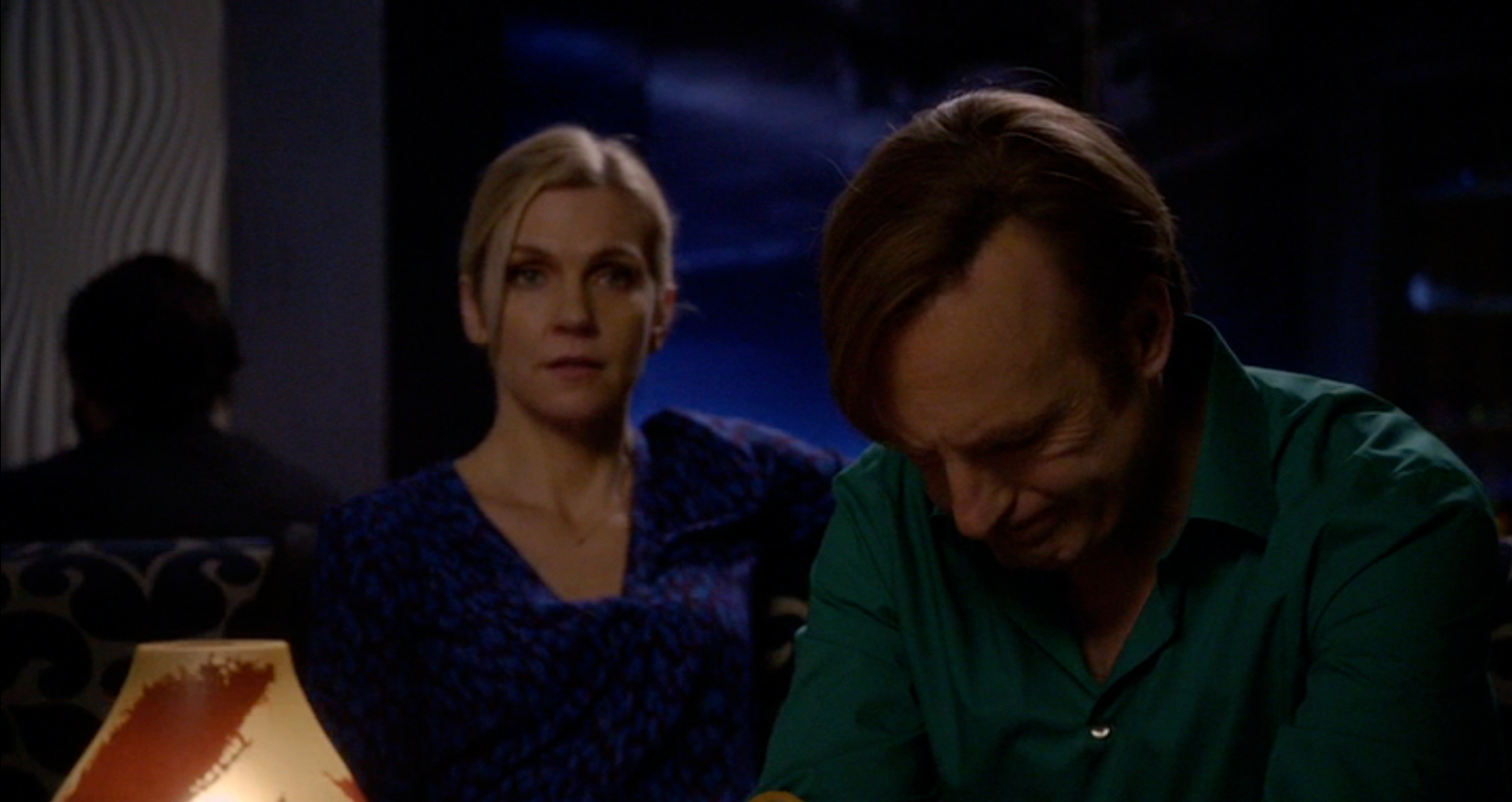

He still takes Kim out (and treats her) because he knows she needs a break, but their usual, playful scamming turns darkly sinister as he seems to realize, in that moment, that he could genuinely break one potential target just for the fun of it. (A moment that clearly worries Kim, but doesn’t scare her off; yet another illustration of the balance.)

I wanted Better Call Saul to be something that I’m increasingly coming to believe it isn’t.

But it is something great. Something that’s grown on its own terms, feeding on our love for Breaking Bad, yes, but giving us a deeply engrossing and elegantly handled transformation story along the way.

Only three episodes in the season remain. And the fact that we already know no character will make wise use of them only makes them more compelling.

Love this write-up! Earlier, I found your aversion for this show detracting time from Jimmy McGill to provide backstory for other “Breaking Bad” characters to be a legitimate concern, but ultimately a preference as opposed to a valid criticism. And on my part, I was rather enjoying the backstory portions. And now I see you’re becoming more like me, which is all I ever ask from anyone.

.

Best part for me is that I can’t remember whether Nacho was a character in “Breaking Bad.” (Please don’t remind me.) That means he is, for me, the wild card, the character who can meet any imaginable fate without my being able to predict it.

.

p.s. I kind of had a crush on Tamara Tunie from her SUV days. Kind of hope Mike gets all up in that.