It’s easy to review horror without giving any indication that you were or are under its spell. You can talk about the inventiveness of the central concept, the performances, the casting. You can talk about the dialogue. You can talk about how predictable or unpredictable it was.

But talk about horror — actually talk, with actual people — and it becomes much more difficult. With very few exceptions, your friends won’t want to hear or talk about the gears in the machine. They’ll want to hear and talk about the film’s effect.

“It wasn’t scary,” and “It scared the hell out of me,” are two of the things you’ll hear most frequently. That’s not necessarily because your friends don’t have the vocabulary to assess the film on deeper levels; it’s because how much it spooked you is the common language of horror, just as how much something made you laugh is the common language of comedy and how much something made you cry is the common language of drama.

Horror, though, is a bit different than those other genres. We know comedy is comedy and drama is drama. We may chuckle or cry a bit when thinking back on a film, but they are still isolated experiences. Our reality is distinct from them, and we know it. By contrast, horror rewires our brains.

Growing up I had a friend who watched the film Arachnophobia, and for years afterward — into adulthood — she would never hang her feet off the edge of her bed, both knowing that there were no spiders waiting underneath and knowing for sure that there were. Another friend once told me about how he played the original Resident Evil and could no longer sleep in the same room as the game’s box; every night he checked to make sure it was somewhere else.

And, of course, there’s me, the biggest baby who still likes horror. When I was little, somebody gave me a gift for Christmas or for my birthday. It was a little plastic bank shaped like the man-eating plant from Little Shop of Horrors. I liked it. Its closed mouth pointed upward and there were little metal contacts on its front teeth. You’d stick a coin there and it would open up and swallow the money. Then I actually watched the movie and it scared the fuck out of me and I didn’t want anything to do with the bank anymore.

Horror makes us see shapes in the shadows. It assigns intent to sounds in the night. It follows us into our dreams and refuses to let us go.

At least, effective horror does. And that’s the great irony of horror; the better it is at fucking with us, the more often we come back. The more we come back, the more it…gets inside of us. For me, John Carpenter is the guy who most often keeps me coming back. I collect his special editions. I try to see any of his films that I can when they pop up in my local boutique theater. I have an autographed poster of his…from In the Mouth of Madness.

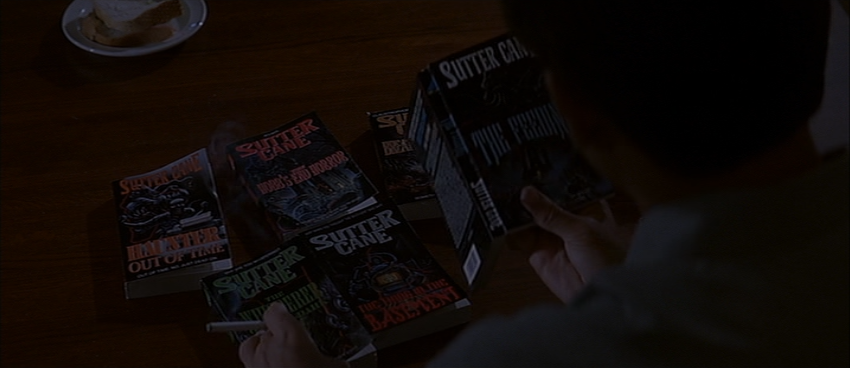

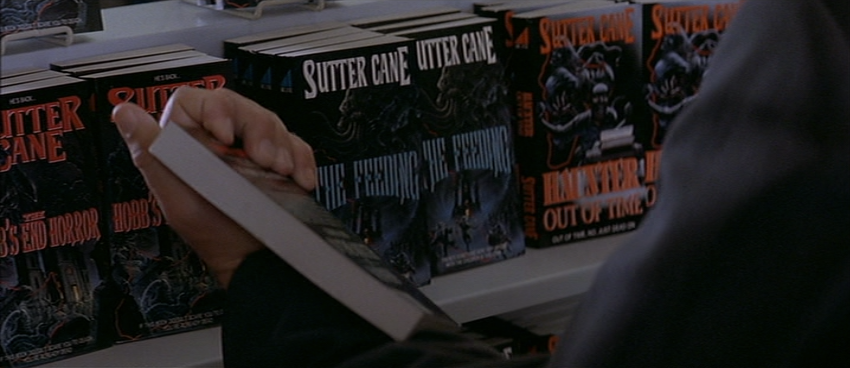

Others, of course, turn to other writers and directors. The characters in this film turn to novelist Sutter Cane. “I just like being scared,” one of them explains. So do his other readers, and we see what happens when his writings get into them.

Sutter Cane is a writer whose books are driving readers insane. It’s rewiring their brains not only to make them afraid of bumps in the night, but to see visions, to lash out, to murder.

It’s clear enough that H.P. Lovecraft is the real-world template for Cane’s works. The little we see and hear of his writing shares Lovecraft’s penchant for description over action, for scene setting over narrative. The effect Cane’s works has on readers is also a nod to the man, as Lovecraft’s writings feature beings so far beyond human comprehension that to even see them is to be driven permanently insane. And, of course, there’s the fact that Lovecraft’s Old Ones are similar to the creatures Cane is bringing to life, but we’ll get to that later.

Another — and arguably stronger — inspiration for Cane is Stephen King.

Allow me to vent for just a moment.

Look up Siskel and Ebert discussing In the Mouth of Madness and find strings of comments calling them out for saying Cane is a King analogue. Look at any review or retrospective that cites King in addition to or instead of Lovecraft and it will be punctuated by angry comments “correcting” the writer. Look at Wikipedia and see that the closest acknowledgement of King its editors will allow is “The film can also be seen as a reference to Stephen King.”

Let me say this clearly: Get off your damned high horse. The Cane / King connection is crucial, important, and obvious. I’ll explain why in my own words, but if you’re already preparing to ignore them, know that Carpenter himself refers to Cane as a King analogue in his own commentary for the film, so nyeh.

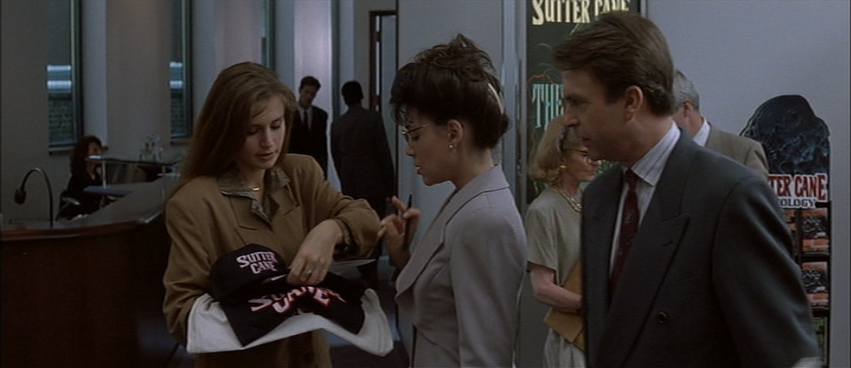

Cane is both Lovecraft and King. He’s Lovecraft’s mind with King’s celebrity. He’s Lovecraft’s influence with King’s merchandising. He’s Lovecraft’s visions with King’s endless releases, translations, and film adaptations.

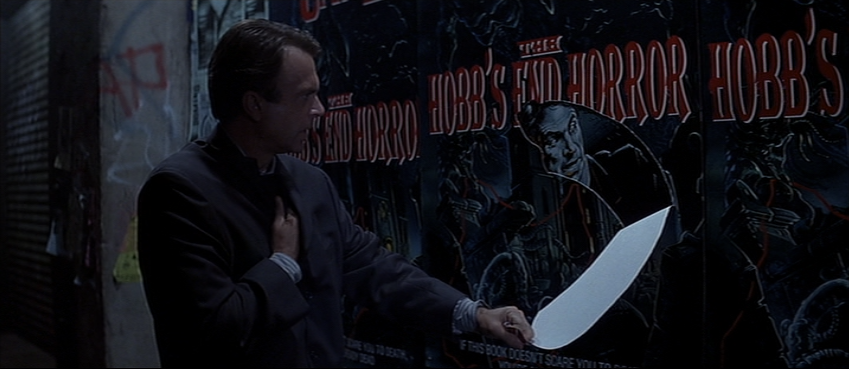

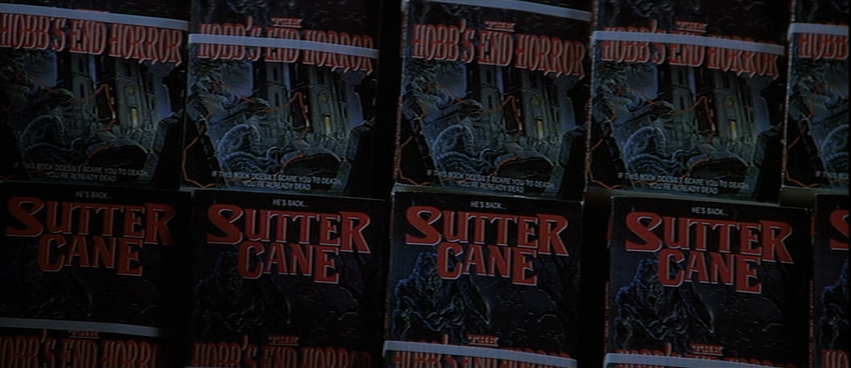

Sutter Cane — even the sound of his name suggests Stephen King, come on now — is a product of his publisher’s marketing. We see his name plastered across marquees, book displays, posters, hats, shirts, coffee mugs, buses.

Do let me know, of course, if that sounds more like Lovecraft to you than King.

Certainly Lovecraft lived and wrote a century ago, before there was such a thing as mass merchandising, but it’s important to remember that he never experienced his own time’s equivalent of fame. Lovecraft was broke. His stories were sometimes published for a pittance, and usually they were rejected. His influence and significance have both grown over the years, but he was long dead by the time that happened. He ended his career believing himself to be a failure without an audience.

Compare that to Cane and the long lines at bookstores — and riots when they run out of copies — and you’ll see that Lovecraft alone isn’t the key to what’s happening here.

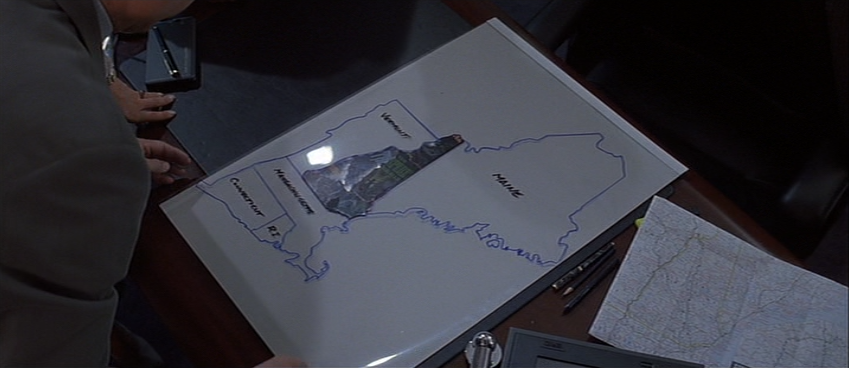

In addition, there’s Cane’s fictional town of Hobb’s End, New Hampshire, the setting for a large number (possibly all) of his stories. That’s not far removed from King’s fictional Castle Rock, Maine, which serves the same purpose. (The states even share a border.)

It’s also, of course, important to remember that “Stephen King” isn’t just a famous novelist Carpenter is likely to have heard of; Carpenter adapted Christine for the big screen. He’s personally familiar with King, with his stories, what they’re like…and how strongly his work resonates with his audience.

That’s what In the Mouth of Madness is about. Resonance. Impact. Effect.

More specifically — though definitely not exclusively — it’s about the effect it has on John Trent (Sam Neill, Memoirs of an Invisible Man), a freelance insurance investigator we meet as he’s being admitted to a mental hospital. He’s visited by Dr. Wrenn (David Warner, Body Bags) who is skeptical of Trent’s madness.

Wrenn and Trent have similar jobs, actually. Trent makes his living poking holes in people’s fraudulent insurance claims, and Wrenn here believes there’s a hole in Trent’s claim of insanity. After all, when Trent arrived he fought the orderlies, cried out for help, swore that he was sane…but as soon as he was locked up he settled down, and used a black crayon to cover himself and the padded walls with crosses.

“They’d almost have to keep you in here, once they’d seen these,” Wrenn says. “Wouldn’t they, John?”

Sure enough, Trent faked at least the severity of his madness so that he’d be locked up. Why? “It’s safer in here now,” he explains.

Trent is our protagonist, which is worth pointing out only because the other two films in this trilogy don’t have them. MacReady is our de facto protagonist in The Thing, but in the same way that he’s that team’s leader: he isn’t, but nobody else will do it. In Prince of Darkness, another version of the film could easily position Brian or the priest (or Catherine) as the protagonist, but the version we got is either an ensemble piece or a film with Satan as its star, depending on your perspective.

Here, it’s Trent and only Trent. And he’s not just the film’s protagonist; he’s also Cane’s.

Trent tells his story to Wrenn, and we follow along. It begins with him hard at work, interviewing Peter Jason (we went over his filmography with Carpenter last week) about his insurance claim, ultimately proving it fraudulent.

Trent’s occupation, demeanor, skill, and fashion sense are straight out of Double Indemnity. He’s like a character plucked from a different story. Believably human, but out of place. He keeps lighting up cigarettes like a character in a movie made 50 years ago, often then being told smoking isn’t allowed, which seems like unexpected and unwelcome information to him.

When he meets Linda Styles — Cane’s editor — his noir sensibilities are brought even more to the fore. She’s prudish and straightlaced, exactly the dame he knows from another story entirely, fully aware that she’ll take off her glasses and let down her hair and reveal the smokey sexuality he hides within. Which is exactly what happens. He even flirts with her with fast, quippy banter that feels more like it belongs in a Raymond Chandler novel than a horror film.

But Trent isn’t a character; he’s a human being. Right? At least, that what he keeps telling people, and trying to tell himself. Twice he says, “Nobody pulls my strings.” At other points he says, “I’m my own man.” “I know what I am.” “I’m not a piece of fiction.” He makes repeated claims that “this is reality.”

The lady doth protest too much, methinks.

As we learn, it isn’t reality. He isn’t a person. And when he meets Cane, the mad author tells him, “I think, therefore you are.”

Again, though, we get ahead of ourselves.

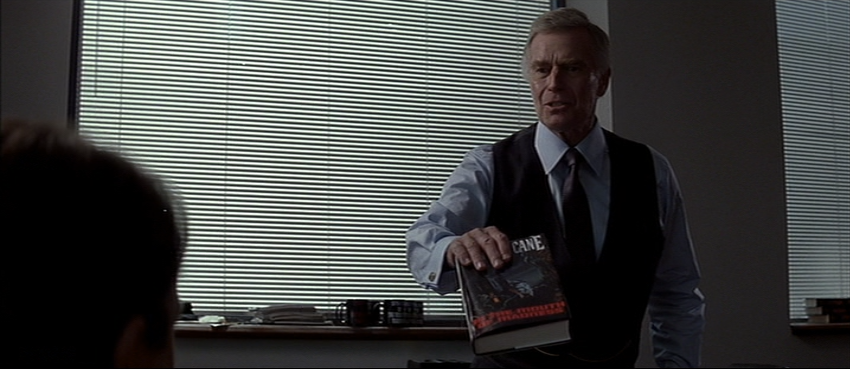

Trent is hired by Cane’s publisher to find the novelist, who’s gone missing. Nobody knows where he is, if he’s coming back, or whether or not he’s still alive. All the publisher knows for sure is that his newest book, In the Mouth of Madness, is at least partially complete, because they received several chapters through his agent.

Cane’s agent would be a great person for Trent to interview, but it turns out they already met.

His agent was driven insane by those sample chapters alone. He smashed through a diner window and attempted to kill Trent before being gunned down by police.

“You’d think a guy that outsells Stephen King could find better representation,” Trent quips. His quip falls flat. He doesn’t realize he’s in a different story now.

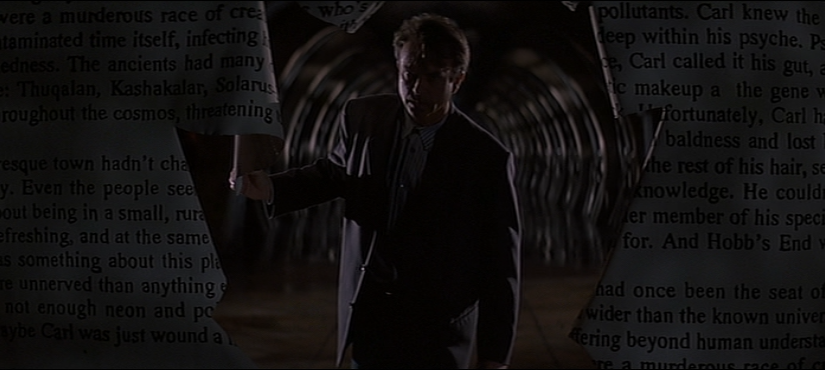

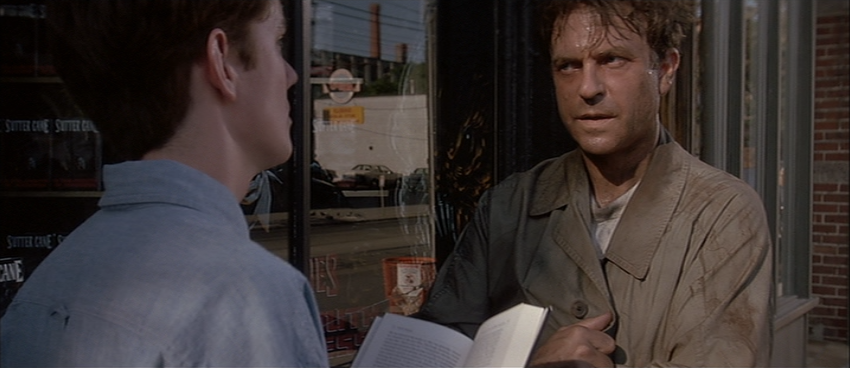

Trent picks up a few Sutter Cane novels and gets reading. They immediately give him nightmares, literally reconfiguring in his mind things he’s seen, such a policeman beating up a vandal in reality who becomes a hideous monster in his dream. His brain is being rewired by Cane, whose writing is (clearly) effective, even if it isn’t very good.

“Pulp horror novels,” Trent describes them to a friend. “They all seem to have the same plot: slimy things in the dark, people go mad, they turn into monsters.” He does concede that they’re better written than he expected, but qualifies that by saying what he really means: “They sort of get to you, in a way.”

Horror doesn’t need to be good in order to be effective, and not all effective horror is good. You don’t need to believe A Nightmare on Elm Street is a good film to see Freddy pop up in your dreams. You don’t need to think The Blair Witch Project is a good film to have your thoughts haunted by it as you walk through the woods at night.

I’ve read a lot of both authors and I’d say that neither Lovecraft nor King are particularly great ones. They both, however, unquestionably have an astonishing wealth of ideas. Ideas that stick. Ideas that are so strong that they succeed in spite of whatever flaws you find in the writing. Trent calls Cane a “hack horror writer,” which might be true but doesn’t matter either way. His writing is effective, and that’s genuinely what is important…both in reality and in this film.

After a long night of studying Cane, Trent notices red lines worked into the cover art of each of his books. He cuts along those lines with scissors and ends up with pieces that fit together to form the shape of New Hampshire, with a single red dot showing, he believes, the “location” of the fictional Hobb’s End. In short, he figures this entire thing is a publicity stunt.

“Makes a great contest, doesn’t it?” Trent asks Cane’s publisher. “Put the pieces together, find the town, win a Sutter Cane lunchbox.”

His publisher swears that’s not the case, and sends Trent and Styles out to find the town, which they do. The invented town of Hobb’s End isn’t on any map, but it does exist, apparently.

The two explore the town, finding everything exactly as Cane described it, right down to a loose floorboard. They encounter characters from the novels, which worries Styles but only further convinces Trent that the entire thing is a setup…an elaborate hoax to freak him out so he will “blab to the media about Cane’s haunted little town, help you sell a few more million copies. Well, fuck that.”

He understandably refuses to believe that a novelist has willed a town into existence and is hiding there, but Styles is genuinely worried. She confesses that they had indeed planned on pulling some kind of publicity stunt — even sent Cane away to get the gossip flowing — but he never showed up at his destination. While manufacturing his disappearance, he really disappeared.

What worries her most is the fact that she’s seeing characters and events in the town that nobody else could know about, because they only appeared in the few chapters of Cane’s upcoming book that he sent to his agent. With his agent dead, only two people know what was in those pages: her and Cane himself.

Without Trent, Styles investigates the church where they think they caught a glimpse of Cane through the doors. She does indeed find him there, working at his typewriter. He expected her, of course. In fact, he wrote her.

“It’s funny, isn’t it?” he tells her. “For years, I thought I was making all this up, but they were telling me what to write. Giving me the power to make it all real. And now it is.”

And that’s what Carpenter posits with In the Mouth of Madness, that Lovecraft and King and Cane and Carpenter aren’t actually founts of incredible ideas…they’re conduits. Somebody — or something — is speaking through them. They don’t close their eyes and generate their own spooky ideas that they can then pass on to an audience; they’re being fed them by something that needs their audience to be frightened into belief. To not just think there might be a monster in the dark, but to believe there is.

Cane ends up being that perfect conduit, and what author wouldn’t pounce on an opportunity like that? Once he learns that ancient creatures are using him and his popularity to bring about their rebirth, well…he keeps writing. Because people are buying it. Because people love him. Because people fight each other and claw each other’s eyes out over the last copy of his latest book at any given store.

He’s a literary celebrity, two words that even in the film don’t often go together.

Cane doesn’t kill himself or warn anybody or fight against the evil forces that use him. He willingly extends his hand so that the devil may shake it. “Someone is going to get fame and fortune in exchange for bringing about the end of the world, right?” we can assume he thinks. “It might as well be me.”

The forces of evil here operate by the opposite rules of those in Prince of Darkness. There, our belief in them made them weak. They were sealed away in a prison, and we were each its wardens. The more we turned our backs, stopped paying attention, stopped caring what it got up to its cell, the greater the chance it had to escape.

Here, our belief makes them strong. The more people who believe in Cane’s slimy, otherworldly monsters, the more people who see them in the shadows, the more people who can be convinced that they lurk under the bed, the stronger they become, and the easier it becomes for them to cross into our reality.

And, it must be said, Cane loves this. I think it’s pretty easy to agree that someone who is offered fame in exchange for destroying the world and replies, “Yes, please,” is a pretty bad guy, but that’s not all Cane is. Cane relishes his status not only as the most famous or profitable author on the planet, but as the most powerful one.

Authors create worlds that both don’t exist and do. They take the form of ink on a page. A series of letters making a series of words making a series of sentences making a series of paragraphs that bring life in the minds and hearts of readers to Captain Ahab, Ebenezer Scrooge, Harry Potter, or Count Dracula. Something that blipped into an author’s mind is encoded as text and circulated, and if it resonates with a large enough audience, the real world adopts it. It takes on a life and an endurance beyond the page. It started in a fictional world, but now it’s part of ours.

Quite literally, the author changes the world.

That’s a seductive concept. And while very, very few writers will create any characters as enduring as the ones I mentioned above, any author who is read at all does transport his fictional concepts into real human beings…where they then live, grow, evolve, haunt. They take on a life beyond the words that created them.

One of the highest compliments I’ve ever received was from somebody who had read one of my stories. She was talking to a friend and something in the conversation sparked a memory for her. Midway through relaying that memory she realized it wasn’t something that actually happened…it was a scene in my story that had stuck with her so effectively that her brain didn’t remember that it was fiction. In her mind, at least for a moment, it wasn’t something she’d read; it was something she’d experienced.

I gave her words, and she gave them life. What an incredible honor that is for any author, any writer, any director, any artist.

Carpenter certainly knows a thing or two how it feels to see his fanciful ideas shaping reality. Halloween gave generations to come a new costume. Escape from New York inspired one of the most iconic video game characters in history. When somebody jokes about a car having a mind of its own by calling it Christine, it’s Carpenter’s film that turned that name into a cultural touchpoint. King reached readers; Carpenter reached everyone else.

Cane reached readers, too, at first, but gradually gained more power. He wasn’t just filling people’s heads with visions of Hobb’s End; he was chiseling it into the New Hampshire countryside. He’d put a monster in this greenhouse, a murderous old woman in that hotel, a pack of violent children near the church.

And he’d do it because he could.

We don’t know if Cane created Trent, but it almost doesn’t matter. Trent has memories of a long life before he ever even heard of Sutter Cane, but those could be artifical. (Or, as Cane would call it, backstory.) Is he a gifted freelance insurance investigator, or is he just a character written as one? A character who only exists out of narrative necessity?

Whether he’s a real person or a fictional character, though, Cane is a powerful enough author that he holds dominion over him.

He toys with him. When Trent tries to escape the town, Cane keeps rewriting things so that every road leading out turns him right back inward. When Trent tries to lose or destroy the manuscript for In the Mouth of Madness, Cane keeps writing it right back into his hands. And in my favorite moment, while a distressed Trent dozes on the bus, Cane appears to him in a dream.

“Did I ever tell you my favorite color was blue?” Cane asks him, and Trent awakens to find everything is now blue.

In truth, this is not unique to Trent. Cane invents characters, uses them, and then writes them out. He reconfigures the world to suit his needs and his vision. Like any author, Cane is constantly editing.

Trent’s tragedy is that he is the only character who remembers the previous edits. His world is constantly being updated around him. People he grew close to are proven to never have existed. He’s been to places that nobody can find. He remembers things that can’t — and could not have — happened, all because he retains memories of those earlier drafts…those earlier versions of reality.

“Reality is not what it used to be,” a man tells Trent. The man came to Hobb’s End just like Trent did. His family was rewritten, and now he’s alone. “The thing I can’t remember is what came first,” he says. “Us, or the book.”

The man readies a gun for suicide and Trent objects. But the man doesn’t hesitate.

“I have to,” he explains. “He wrote me this way.”

As I discussed in the two previous entries, Carpenter’s films are about their characters figuring out the rules the govern the world around them. Sometimes they succeed, sometimes they fail. Trent is in the horrifying position of trying to figure out rules that are always changing, and it’s a miracle he retains his sanity as long as he does.

What finally breaks Trent is a conversation with Cane’s publisher. He learns two things. The first is that Styles never existed. Of course she did; he has memories of her and she was an integral part of the story. In fact, rewatching the movie with this in mind, we see that Styles and her boss interact a number of times, meaning Cane really did rewrite things to remove her from the story — and the world — entirely.

That’s frustrating to Trent, but not unexpected. He’s used to these tricks by now.

Then he learns something else. While explaining to the publisher why he will not turn over Cane’s final manuscript, the publisher tells him that he already has. Trent brought it to him months ago. It’s been in stores for weeks. The movie will be released shortly.

Throughout the film Trent fights against what Cane keeps telling him is his character’s purpose. Trent is the character who travels to Hobb’s End to retrieve the manuscript, get it published, and unleash unthinkable horror upon the world. Trent refuses at every turn to play his role, no matter what the emotional or psychological cost of noncompliance.

And then he learns that he did it anyway. If Trent wouldn’t cooperate, Cane would just write that he’d done it already. We don’t need to have a chapter in which he does…we just need a chapter in which he did.

Which leads to Trent either fulfilling Cane’s circular narrative or breaking out of it; he picks up an axe and murders somebody, just as Cane’s agent tried to murder him at the film’s start.

It’s an act of calculated madness. Cruel, but he feels he has no other choice. “Every species can smell its own extinction,” he tells Wrenn.

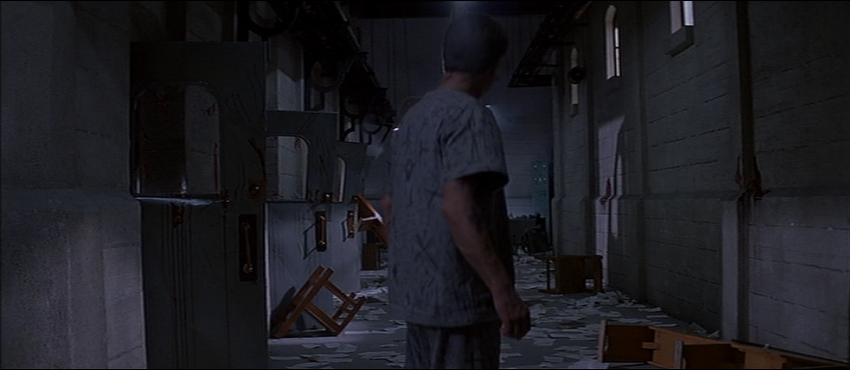

If he’s going to survive the otherworldly invasion brought about by Cane’s latest masterpiece, he’s going to need to be somewhere very secure. He gets locked away in the institution. It’s a cruel and dehumanizing place, but it’s preferable to the literal apocalypse unfolding outside its walls.

We don’t see much of the apocalypse, but we see (and hear over the radio) enough to know the situation is hopeless. Mankind is in the active process of being exterminated. Cane’s tales were so believable that people knew his monsters existed…and they certainly didn’t stop believing when the monsters actually showed up to kill them.

But even then, as the world burns, Cane isn’t done running his favorite character through the wringer.

The door to Trent’s room swings open. There’s no explanation for it. There’s no need for one. Cane is long past hiding his narrative contrivance.

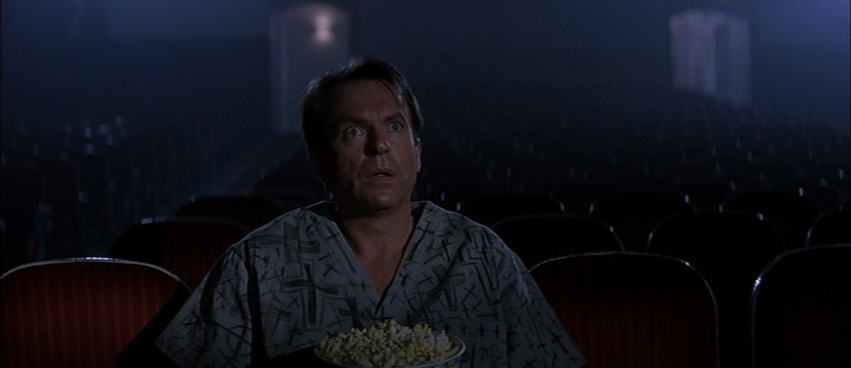

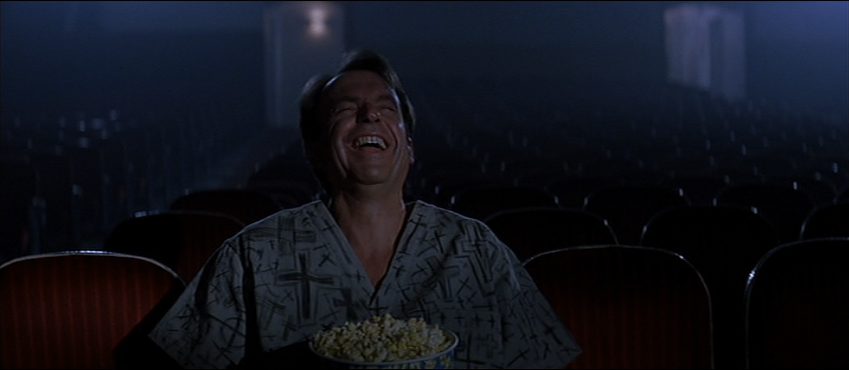

Trent stumbles out. He encounters no other human being. The movie theater is within easy walking distance of the mental institution. Why not? That’s where we need it to be. It’s playing the film adaptation of Cane’s brand-new novel, In the Mouth of Madness.

Whatever was going to happen already happened. However much Trent managed to postpone tragedy — if at all — he can’t postpone it anymore. He might as well pour himself a bucket of popcorn and enjoy the show.

He sees himself on the big screen ranting about reality, insisting that reality is what he says it is, promising that it is solid and unchangeable…and the Trent watching the film laughs.

And laughs, and laughs.

What else can you do?

Early in the film, Trent and Styles debate the nature of reality. She tells him that reality is just an agreement everyone has with each other, and that what really scares her about Cane’s work is how scary reality would be if it shared his point of view.

Which is what happens. It’s what Cane wants to happen. It’s what Cane rubs Trent’s nose in at the end of the film. The Trent on the screen — actual clips from the movie we’ve just seen — was the real Trent. Now the real Trent is eating popcorn and watching it. Reality and fiction have switched places.

It’s a pretty good joke, even if Trent is the only one left who can appreciate it.

Of course, there’s another possibility: Trent really did go insane, and he did so very early in the film.

His visions and nightmares start not after but during an all-night binge of Sutter Cane. Anything we see after that could be representative of his descent into madness. Seeking out the author, exploring the town he just read about, meeting characters from the story…it’s possible that none of that happened.

And if that’s the case, well…what did happen?

We do know that Cane’s writings caused insanity, that his horror rewired minds, that his fans became fanatics. (“Do you read Sutter Cane?”) There are riots. Violence. A crazy man attempts to murder Trent with an axe. Readers bleed from the eye, move through life in a daze, ignore their personal hygiene, mutter seeming nonsense. They detach from reality. Whether that’s due to Lovecraftian Elder Gods speaking through Cane or just due to his particular, creative approach as an artist, the result is the same.

Trent’s mind wouldn’t even have to stretch very far to imagine what at first seems like a very complex hallucination. As Cane explains late in the movie, “All those horrible, slimy things trying to get back in? They’re all true.” The horror we see unfold in Hobb’s End, the specific motivations of the hideous creatures forcing their way back into our world…well, Cane already wrote that, and Trent just read it. All his mind needs to do is let fact and fiction change places.

Cane’s agent, as well, never traveled to Hobb’s End to see the monsters; he only read the sample chapters Cane sent along. Ditto everyone else participating in the violence in the streets. They didn’t go on the same pilgrimage Trent thinks he did; they just read the books. We don’t know what’s happening in their minds. Trent doesn’t know what’s happening in his.

And so when Trent appears outside of a bookstore, disheveled, carrying an axe, and starts hacking away at a Sutter Cane fan…is that an act of calculated madness to keep him safe from ancient beasts? Or, y’know, is that actual madness because he thinks the ancient beasts in Cane’s writings are real?

Remember that Dr. Wrenn, after listening to Trent’s entire tale, dismisses it. He is a professional who works with the mentally ill on a daily basis, and after listening to Trent’s elaborate, paranoid ramblings, he doesn’t see it as anything of particular worry. The guy is crazy, and now he’s in a cell. Wrenn is satisfied, professionally, with that alone.

Of course, then, what of the apocalypse? Without the monsters clawing their way back to an Earth that once was theirs, what ends the world?

Well, as we’ve been told, it ends with a whimper. We never see the monsters outside of either Trent’s tale or his point of view. The murders and deaths and killings are real, whatever Trent does or does not see as the impetus.

It’s his mind assigning that form to something very simple: The most widely read author on the planet is driving his readers nuts.

Enough people read Sutter Cane that the number of insane quickly outnumber the sane.

“Sane and insane could easily switch places,” Styles tells him early on. “If the insane were to become the majority, you would find yourself locked in a padded cell, wondering what happened to the world.”

She’s making conversation. Nothing to worry about, really.

In the Mouth of Madness is often considered Carpenter’s last great film. I don’t buy that, but I also know I’m a bit more willing to search for merit than most people. (Seriously, though, the existence of Vampires is evidence that this can’t be his last great film.) If this movie does end up standing as his final major cultural achievement, though, that’s not such a bad thing. It deserves attention, however it gets it.

It’s not a movie that I hear people talk about often. In fact, I only ended up watching it because a friend told me I needed to. It had been on my radar as a love letter to Lovecraft, but beyond that I didn’t know anything.

And while I do think it’s the weakest of the Apocalypse Trilogy, that’s less to do with any failing on this film’s part than it is to do with the incredibly high bar set by the other two films. Taken on its own merits, In the Mouth of Madness is a weird, memorable, and often very funny film.

It’s the least scary, but that’s almost certainly because its central danger is the most complex. It’s relatively easy to put yourself in the place of someone who can no longer trust anybody he knows, or someone tasked with stopping an evil presence she doesn’t even understand. I think it’s far more difficult to put yourself in the place of someone who is a character doomed to remember all the rewrites of the story he occupies.

Which, to be totally honest, is probably why Carpenter leans pretty heavily into comedy here. It doesn’t come at the expense of horror, but it keeps us tagging along, and keeps us interested in a situation it’s safe to say none of us will ever experience.

I like that, actually. I like that the Apocalypse Trilogy closes off with a film that both finally brings us the apocalypse and keeps it at a distance. We already can’t relate to Trent’s plight, so having his film be the one that actually faces the apocalypse makes it something easier to enjoy as we sit in the dark, watching, stuffing our faces with popcorn.

It’s just fiction. It’s just something some writer came up with somewhere. We just like being scared. Nobody pulls our strings.

And we’ll laugh, and laugh, and laugh.

Happy Halloween, everyone. Thank you for reading.