Fiction into Film is a series devoted to page-to-screen adaptations. The process of translating prose to the visual medium is a tricky and only intermittently successful one, but even the fumbles provide a great platform for understanding stories, and why they affect us the way they do.

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest is the film that originally piqued my interest in the process of adaptation. I first saw it in junior high. (This surprises me now, as there’s a good deal of profanity, some nudity, discussions of rape, and simulated masturbation, so we must have had a pretty inattentive substitute that day.) Toward the end of high school, I picked up the novel…and I was shocked by something the moment I started reading it: Chief Bromden was the narrator.

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest is the film that originally piqued my interest in the process of adaptation. I first saw it in junior high. (This surprises me now, as there’s a good deal of profanity, some nudity, discussions of rape, and simulated masturbation, so we must have had a pretty inattentive substitute that day.) Toward the end of high school, I picked up the novel…and I was shocked by something the moment I started reading it: Chief Bromden was the narrator.

This is an experiment I’ve enjoyed repeating over the years. Whenever I meet somebody who’s only seen the film, I casually mention that the book is narrated by the Chief. Every time, to some degree, I’m met with disbelief and confusion. They go through that same, silent questioning that I went through way back then. Questioning which, I believe, is a testament to the strength of Milos Forman’s adaptation. Bromden narrating the source material doesn’t just land as a quirky surprise…it makes it immediately clear that the book must be a different kind of story entirely.

And it is. The shift in perspective narrows and sharpens the film’s focus, but it also sets into motion waves of less-perceptible effects. This ends up creating a welcome duplication of the original experience, familiar and just far enough removed that the film was able to take on a very deserved legacy of its own.

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest is probably my example of an ideal adaptation; instead of having one version that trumps (or attempts to trump) the other, we have two versions, existing in two different media, functioning together and also independently. A massive, important, gut-wrenching statement in print managed to become also a massive, important, gut-wrenching statement on film. They share a title, they share a roster of characters, and they arguably share a grander social statement, but the execution in each version is so perfectly tuned to its medium that they’re easy to keep separate. A single ray of light split into two similar but distinct images.

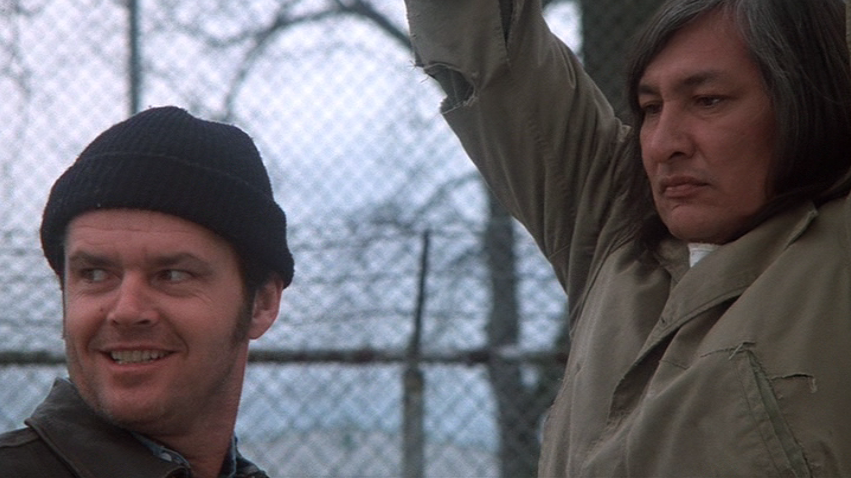

The story of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest doesn’t, on the surface, feel different between the book and the film. Randle Patrick McMurphy — a brash, charismatic criminal — feigns mental illness so that he can ride out his prison sentence with relative ease in an institution. It works, but he soon finds himself locked in a fateful (and ultimately fatal) struggle with Nurse Ratched, who rules with unchecked authority over her numb and defeated patients.

The struggle between McMurphy and the Big Nurse (as Bromden calls her in the book) is what nearly anyone would talk about when asked to discuss the plot of either version. Rightly so, but its not the only plot Kesey set to the page, and it’s only one filter through which his novel explores the world. Forman — I’d say wisely — eschews everything that doesn’t tie directly into this plot, building continuously and without digression toward the showdown between these two giants. While that means that his film loses a lot of Kesey’s warped, cynical playfulness, it also results in a sharper work…one that has a single, specific, inevitable outcome. There aren’t other threads to wrap up or questions to answer; a story of many things finds what matters most to what it neeeds to say, and discards the rest. It’s a movie about its conclusion; no blinking, no distraction, and nowhere to hide. It knows what it’s doing, like McMurphy. And like McMurphy, it barrels forward anyway, knowing full well that it won’t find a happy ending.

The book takes its time. There are lighter, humorous interludes. It moseys along and takes every opportunity to enjoy (or, at least, linger upon) the view. It knows what has to happen as well, but it finds sober, voyeuristic pleasure in the low-stakes poker games and quiet interactions that its cinematic twin ignores. The novel and the film amount to two journeys past all of the same landmarks, but at a much different pace, with a very different tour guide.

Both approaches work, and they work equally well. This is because Kesey and Forman are both in command of their form. At no point does either version of the tale stray from its creator’s intentions. They’re equally potent. Equally memorable. Equally brutal. They’re different, but I think it would be very difficult to declare with any confidence that one is “better.”

Sweeping Bromden from the central role does more than shift the weight of the story. After all, the novel actually weaves three levels of narrative; by edging him out of the spotlight, we end up with the film’s (cold, deliberate) one. The novel features the McMurphy / Nurse Ratched power struggle, of course, but there’s also the story of Bromden’s tribe (an exploration of America’s treatment of its native population), and his intricate hallucinations of an oppressive social force that he calls The Combine.

All three of these are integral to what Kesey considers to be the story. Forman, by contrast, isn’t interested in Bromden’s background or his daydreams. Very little of either of those makes it into the film, because to Forman’s story, they’re irrelevant; the director obviously came away from Kesey’s book with a powerful message, but it didn’t have much to do with the plight of the American Indian. And so we don’t need Bromden in the central role…which has the logistical benefit of Forman not needing to maneuver the seemingly deaf/dumb Indian into every important scene; in the film, the character simply does not appear where he does not fit.

But with him out of the way, we lose, too, his unreliable narration.

Kesey had a great deal of morbid fun showing us the experience through Bromden’s eyes, eyes crucially warped by the specter of mental illness. Stripping Bromden of narrative detail meant that we lost much of the loopy charm (a sequence in which Santa Claus visits the ward and is forcibly committed [“They kept him with us six years before they discharged him, clean-shaven and skinny as a pole.”] is a cruel delight that could only possibly have a home in the book), but in the absence of an unreliable narrator, the central conflict of an irresistible force meeting an immovable object gains potency.

With Kubrick’s Lolita the source material lost a massive amount of its identity in the absence of an unreliable narrator, but that’s mainly because Kubrick failed to replace this crucial component of the novel with much else. Forman, on the other hand, knows exactly what to do in the absence of Bromden’s unreliable narration: he doubles down, hard, on the reality of the situation. Bromden’s fantastical narration made for some great (and chilling) reading, but Forman offers no distraction. No respite. This is real. This is happening. And you are going to have to endure every moment. Where Kesey dazzles, Forman refuses to blink.

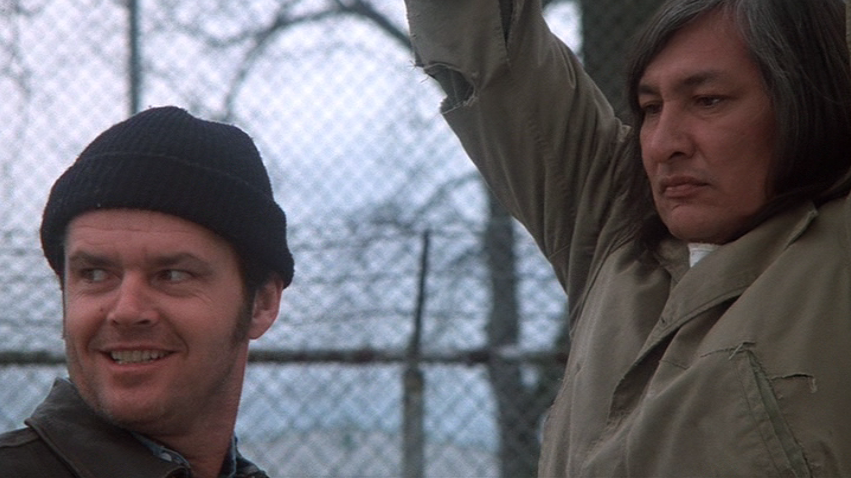

Of course, Forman had a great reason to devote his attention exclusively to the novel’s central conflict: two incredible actors inhabiting the necessary roles. To distract from their performances — however artfully — would have been criminal. Jack Nicholson and Louise Fletcher are the two main reasons the film works as well as it does, and their roles in making this film a success — of any and every kind — cannot be overstated. Most literary adaptations would kill to have just one actor that perfectly inhabits a character; One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Next has two.

Both of them illustrate (if it still needs illustrating) why it’s far preferable for an actor to inhabit rather than simply resemble a character. Neither Nicholson nor Fletcher match Kesey’s physical descriptions at all, but it would take an extraordinarily warped perspective to conclude that this meant poor casting. In fact, Ratched’s physical appearance, almost entirely a creation of the film, is one of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest‘s most enduring visual touchpoints; her hair and wardrobe now serve as a convenient shorthand for a very specific type of character — always female, interestingly — and we see it in everything from the deliberate homage of Cloris Leachman in High Anxiety to the suggested similarities of Tilda Swinton in Moonrise Kingdom. Nurse Ratched’s physical appearance sticks with us long after the film is over. It’s a triumph of rendering the ordinary horrifying.

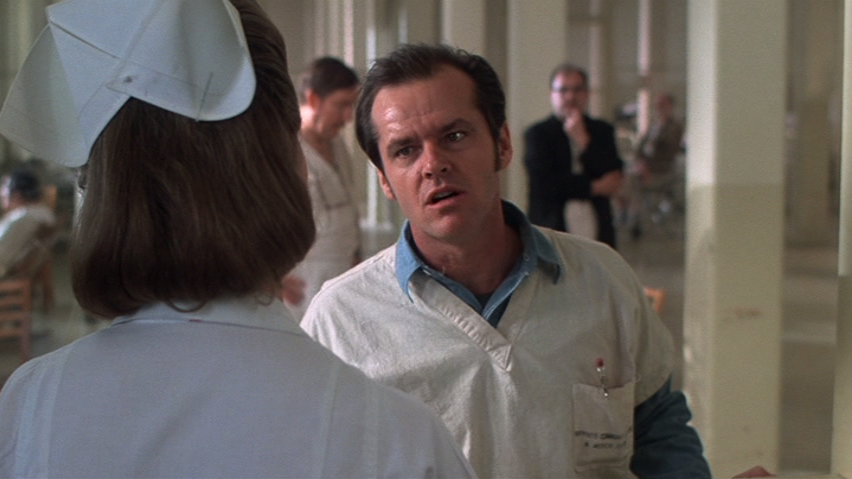

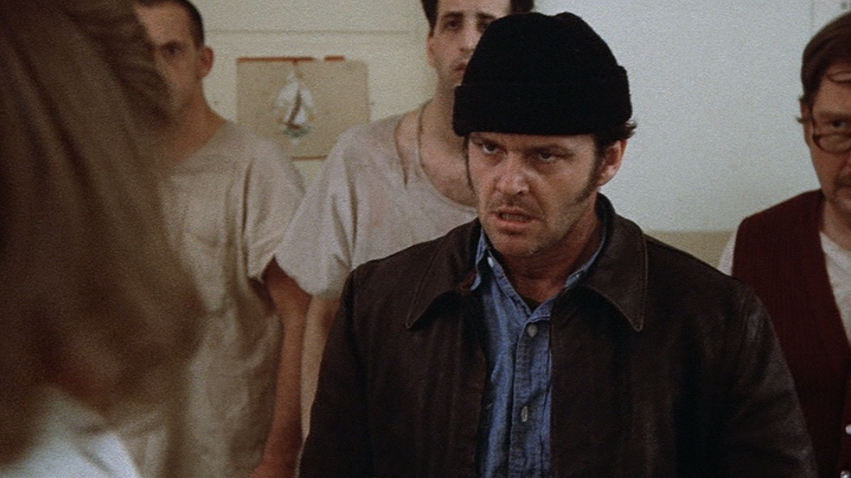

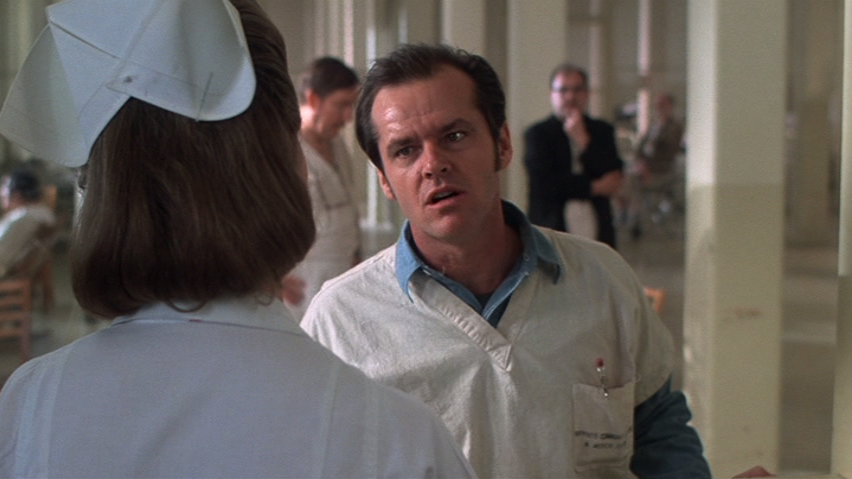

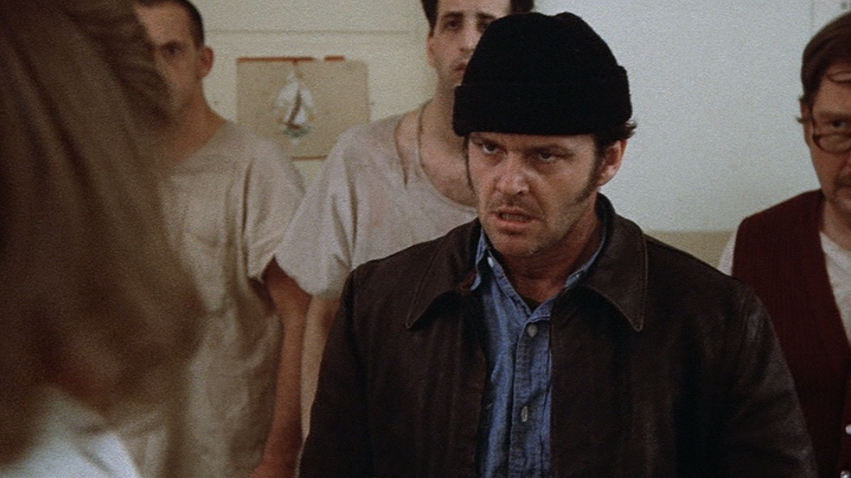

Nicholson plays McMurphy as an agent of calculated chaos. He rips into the meticulous order of the ward from the moment he’s uncuffed (literally that moment, as the first thing he does is whoop joyously…something that even this early in the film we know doesn’t happen often here). He sets about introducing himself to the other patients, interrupting their games, and making sure they know his name. He treats them — to their clear surprise — like human beings. That doesn’t mean that he treats them well, exactly, but that’s okay. He treats them the way he’d treat anyone else. And that in itself is enough to set the wheels in motion: the patients begin to suspect they might not be so different after all.

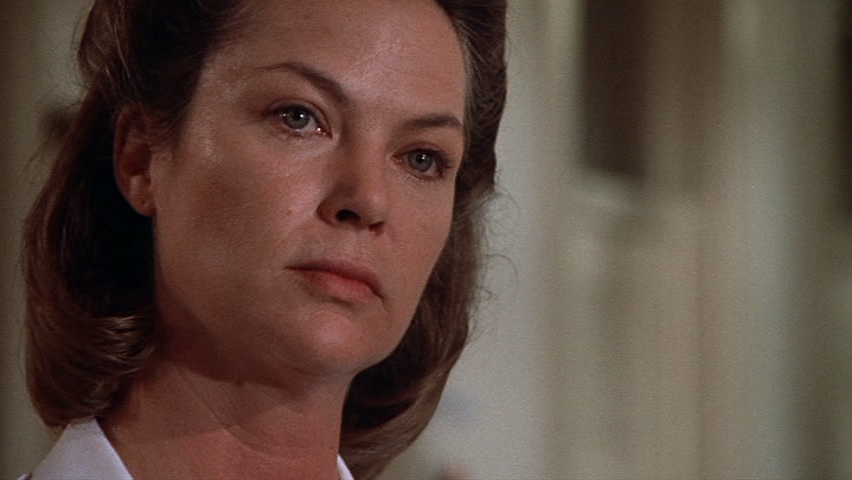

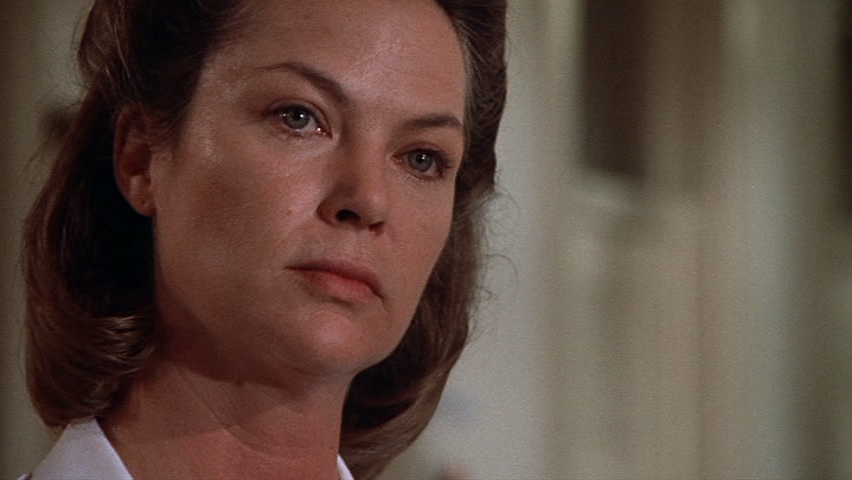

By contrast, Fletcher inhabits Nurse Ratched as a looming wraith. She rules her ward not with an iron fist — a simplification that must have been tempting for both authors of the tale — but with perfect calm. With a smothering delicacy. With glares and implications. And she is — pardon the language — fucking terrifying.

She’s a villain perfectly secure in the knowledge that she can never be threatened, because she also has the final say in who wins. As Bromden observes in the book, you can probably beat her once, but you need to keep beating her forever. There’s no victory state for her hypothetical antagonist…just an endless series of wins and losses until, all at once, there are no more wins.

In the struggle between them McMurphy is the clear hero, but at no point is it reduced to a simple conflict between “good and evil.” McMurphy may be the more humane combatant, but he fleeces, cheats, and uses his fellow patients in service of his own ends…and saying nothing of the fact that he was imprisoned for statutory rape, which is something he even brags about. And Nurse Ratched, for all that is clearly wrong with her methods, is ultimately in her position for a reason: many of her patients do have legitimate mental health issues, and her ostensible concerns (medication, respect for the schedule, the dangers of McMurphy’s schemes) are sound.

Nurse Ratched may be doing a number on the confidence of the men in her ward, but she’s seen (in both the novel and the film) by the rest of the hospital as one of their most valuable members. We also see her at her worst, but to her supervisors and colleagues, she’s great at her job and a valued member of staff. Clearly she’s doing something that at least seems like good work, and it can’t all be illusory.

The complicated nature of the struggle is part of why it works so well. Nurse Ratched isn’t pure evil, which is why she’s so often able to stymie McMurphy; she makes fair points. Her intentions may be less noble than his, but her reasoning — she makes very sure — is solid and defensible. And McMurphy isn’t pure good, coming across as an obnoxious braggart while still serving, remarkably, as a savior. She’s a cruel angel of mercy, and he’s a selfish asshole who makes the ultimate sacrifice. such a balance is hard enough to achieve in writing; on screen, Nicholson and Fletcher each achieve the impossible.

Fletcher masterfully embodies the personable horror that is Nurse Ratched. Hers is the most natural portrayal of an unnatural terror that I have ever seen, and her flat expressions and piercing glares are positively withering. The film does such a great job of building the dread one feels when she just steps into a room that when she finally has reason to bare her teeth in anger, it’s genuinely scary.

Hers is a silent brutality…effortlessly chilling and immensely dangerous without displaying any emotion whatsoever. The moment emotion does come to the surface, it’s unbearable. We know exactly how she maintains order on her ward; keep everyone that close to breaking, and it doesn’t take much to finish the job.

In the book, we Bromden in a position to tell us all of this in as many words. In the film, Forman conveys all of the same things visually…hanging on her icy glare long enough for us to sense, innately, in our bones, how unbreakable, untouchable, undefeatable she is. She reduces patients to tears and dismay without so much as raising her voice. She fixes the aggressive and the docile with the same look, and they wither equally.

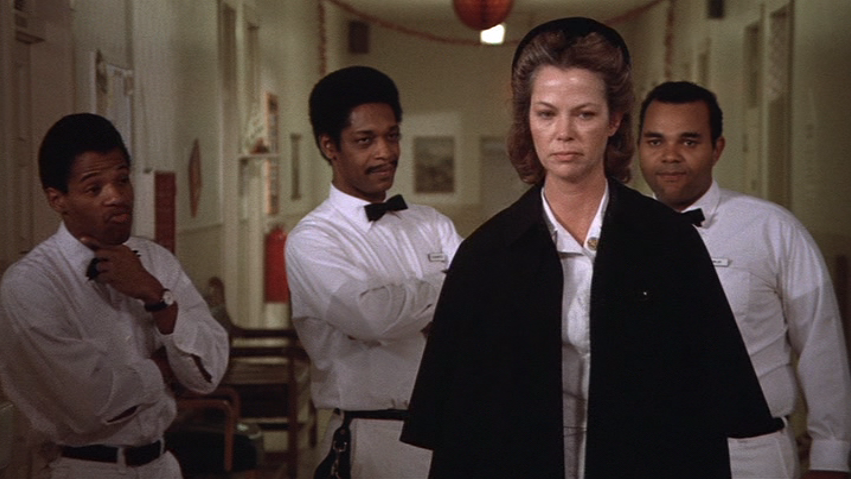

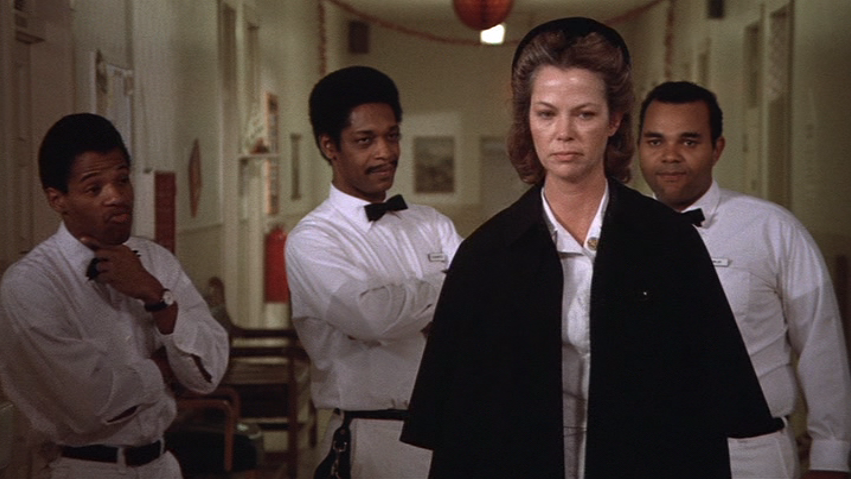

One interesting thing Forman does is forbid her, nearly always from sharing the frame with any of her patients. In passing, yes, there are times that she does share space…but when she does it’s with McMurphy, who is meant to be seen as toppling barriers anyway. The rest of the time she engages with them we cut from the patient to Nurse Ratched, and then back to the patient. She exists behind invisible boundaries that they dare not cross, and which she is perfectly happy to maintain her end. She does not share their space…and she does not allow them to share hers.

Forman emphasizes this silently, visually, gorgeously. The camera functions like the glass window of the nurses’ station; it invisibly isolates the patients from the one who is ostensibly there to help them. And, like that glass window, it’s McMurphy who eventually shatters it.

She is, however, framed frequently with other members of staff, in particular her three orderlies. The orderlies, in turn, are often framed with the patients, and this establishes — completely visually — the entire caste system of the ward.

The patients are on one end, the Big Nurse is on the other. The orderlies go where they’re needed in order to execute Nurse Ratched’s wishes, and she never needs to get her hands dirty. Bromden tells us all of that in the book. Forman doesn’t say a word.

And when this visual restriction is shattered for good with the film’s climactic strangling, we feel a barrier being destroyed. McMurphy takes control of Nurse Ratched’s space at last…and we know, unquestionably, that this must be the last time it happens as well.

Though Forman’s take on One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest feels like a pretty straight adaptation on the surface, there are a lot of significant alterations, nearly all of which benefit the film.

For instance, we don’t get the series of patient deaths that we do in the novel. There, at least three patients (Old Blastic, Rawler, and Cheswick…the latter two by suicide) die before the fateful ward party that takes Billy Bibbit and (indirectly) McMurphy, but in the film Billy is our first casualty, and it ends up having more weight in Forman’s telling as a result. The film doesn’t let show us patients dying, so when Billy cuts his throat we feel it all the more deeply; this wasn’t something that we thought could happen.

The death of Billy has more bite in the film, I’d argue, and that’s probably because it was unprecedented. Billy isn’t the next death…he’s the death. And when McMurphy reaches for Nurse Ratched’s throat, it’s not because it happened again, but because it happened at all.

And just as Billy’s death is repositioned as the death, McMurphy’s role becomes singular, too. In the novel, we get a few flashback featuring a patient known as Taber, who questioned Nurse Ratched’s authority and methods. Taber was, essentially, pulling the same duty as McMurphy. He needled the Big Nurse, refused to take his medication, and raised issues that the other patients were too docile or embarrassed to raise. Nurse Ratched, in return, made sure that he was embarrassed, abused, and eventually broken by electroshock therapy. Though he was discharged, he was not the same man. His story, relayed briefly by Chief Bromden in the book, is McMurphy’s entire arc in micro. A nice touch, but in comparison to the film this makes McMurphy less of a singular force. In the book he’s the latest in a line of disruptions, whereas in the film, he is the disruption.

Most interesting about this change is the fact that Forman includes Taber in the script. He’s played by an underutilized (but still very good) Christopher Lloyd, and he’s right there on the ward with McMurphy. What’s more, many of his lines from the book are given to McMurphy.

While it would have been easy to not include Taber at all, Forman wants us to see that what happened in the book did not happen in the movie. We don’t get to imagine that at some point in the past there was a Taber. Forman wrenches him out of the flashbacks and sits him down right where you can see him, all so you know, beyond the shadow of a doubt, that McMurphy isn’t just offering another chance to the other patients; he’s offering the only chance they’ll ever have.

Probably the smartest major change, though, is Forman’s abandonment of the “Matriarchy” nonsense.

In most ways, Kesey’s novel has aged extraordinarily well. It’s gorgeously written, effectively harrowing, and socially sharp. Yet his seeming concerns about the Matriarchy read as preposterous — and more than a little embarrassing — today. The idea that men would be castrated (literally and figuratively) by an all-powerful Womanhood, to whom they’d sacrifice their autonomy, and which would hold all of the power and authority in the nation, reads even sillier today than it must have in 1962. Perhaps back then it was possible to see this as a cause for some concern; and, hey, for all I know One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest single-handedly prevented America from sliding helplessly into the tyrannical grip of unbridled femininity. I don’t and can’t know. Today, though, it’s patently absurd, and the belief that women hold (or are in danger of holding, or who would systematically destroy mankind once they managed to hold) absolute power requires a complete disconnect from anything even resembling reality.

It’s tempting to handwave the book’s suggested misogyny as stemming from the diseased mind of Chief Bromden, but it manifests itself in too many facets (several of which have nothing to do with Bromden) to be entirely a product of his narration. It’s Bromden’s mother, it’s Nurse Ratched, it’s Harding’s wife, it’s Billy’s mother, it’s even the teenage girl McMurphy rapes. The Matriarchy — which is mentioned and cautioned against by name — is a very real threat in the world of novel, and it’s one that beats down each of the men. Forman, intelligently, ignores this entirely, and even announces as much at the beginning of the film when McMurphy is admitted. There we get a shot of patients from other wards looking upon him with curiosity…and they’re women. In the novel, the patients are exclusively male. Here, with one shot, Forman brushes aside the distasteful paranoia and lets us know something important: these things are horrible not because they’re happening to men, but because they’re happening to people. Gender doesn’t enter into it.

This is also reflected in the revised role of Dr. Spivey, who in the film is ineffectual, rather than henpecked. In the book he is present at all of the ward meetings, mainly to demonstrate the fact that he’s under the thumb of Nurse Ratched as well, even though he is technically her superior. In the film, he rarely leaves his office, meaning we get less of a sense that he’s under her (or anyone’s) control.

This is important, because this version of Dr. Spivey is not cowing in fear…yet he still fails to be of much use. He’s not rendered powerless by the Matriarchy; he’s simply not very good at his job.

If the film has a weakness (and I’d personally say it has a few), it’s the fact that it’s made up of big scene after big scene. As nice as it is to have the sharper focus of Forman’s vision and the inexorable march toward the climactic gut-punch, the novel’s quieter scenes are missed. Nearly every scene in the film is a confrontation, the build-up to a confrontation, or the aftermath of a confrontation. It’s exhausting; it can feel draining to watch…which, admittedly, is likely enough a deliberate way of getting us to feel some of what McMurphy must feel. But this comes at the expense of the feeling of misfit community that the book conjures up so wonderfully. Card games, small talk, a trip to the hospital library. Scenes that, sometimes, do little more than make the tiny universe of ward life feel more real…but that’s exactly why they’re missed. When we jump from big moment to big moment, that sense of gradual build is sacrificed in favor of something more like an emotional slideshow.

Much of these missing quiet moments are down to the reimagining of the character Harding, who in the novel serves repeatedly as McMurphy’s verbal sparring partner. That Harding is as intelligent as McMurphy is brash, and they form a begrudging respect for each other; each has what the other is too proud to admit he wants. Like McMurphy, the novel’s Harding is one of the least sick men on the ward, and most of his troubles (such as they are) seem to stem from worries about his wife’s sexuality, and suspicions about his own. Outside of McMurphy and Bromden, he’s the most important of Kesey’s patients, and it’s through him that most of the novel’s foreshadowing unfolds.

In the film, Harding is more helpless than intelligent, and Nicholson’s McMurphy, for whatever reason, can’t stand him.

It’s a major shift in dynamics from the book. Book Harding rises to McMurphy’s taunts…and the two settle into a kind of unexpected friendship. Film Harding shrinks before McMurphy’s taunts…and therefore never earns his respect. The book and the film, as a result, seem to form a pair of realities, each of which exploring the way in which Harding’s role changes, based upon two different, hypothetical reactions to McMurphy.

So far away from the often chummy banter the two share in the book, in the film McMurphy ruins his Monopoly game, spits a pill in his face, cuts in front of him in line for medication, teases him about his sexuality, kicks him out of the basketball game, and — the biggest slight of all — he introduces him as Mr. Harding before the fishing trip, whereas everyone else gets to be Dr. Cheswick, Dr. Taber, Dr. Scanlon (the famous Dr. Scanlon), and so on. In short, McMurphy treats Harding noticeably worse than he treats the other patients.

It’s an interesting change, as though Book McMurphy sees in him a source of valuable advice (and information), while Film McMurphy sees him as someone who needs to be knocked down a peg. This, I think, is due to the fact that Harding’s purpose in the novel is rendered redundant on film. In the book Harding had to relay information to the reader; he was the only character who could. Bromden can’t (ahem) speak and isn’t to be entirely trusted anyway, Nurse Ratched wouldn’t dare vocalize her intentions, McMurphy is new on the ward and learning things along with us…but Harding fit the role nicely. He was relatively sane, relatively reliable, relatively friendly, relatively talkative, and had been on the ward long enough to know which end was up. In the book, his was the most trustworthy voice.

In the film, however, there’s no need for him. Forman conveys with quiet visuals what Kesey detailed in meticulous text. The audience picks up on things by virtue of simply seeing them, and the film trusts them enough to fill in the blanks.

Forman also skimps decidedly on the foreshadowing. Whereas Kesey needed Harding to explain the nature of electroshock therapy or lobotomy, Forman doesn’t want him talking. When those moments hit, he wants them to hit both hard and unexpectedly. Just as the string of deaths was stripped from the film and Taber was stripped of his role as proto-McMurphy, Harding was stripped of his warnings. Forman didn’t want the audience to be told what was coming. The audience would know, because that’s how inevitability works, but somehow it’s scarier, more effective when it’s not spoken of aloud.

I’d argue that Forman’s rollout of horrors is handled more artfully than Kesey’s, but that’s just a matter of opinion, and even then I can’t say that I have a strong preference either way. What I do prefer is that Forman’s methods force us to side with McMurphy. In the novel, we know ahead of time what he’s getting himself into, and we have every right to question his intelligence (and, erm, sanity) when he pushes forward anyway. In the film we learn as he learns…which is as the punishments are lashed upon him. This makes us feel protective, feel angrier on his behalf, and see clearly the importance of his rebellion.

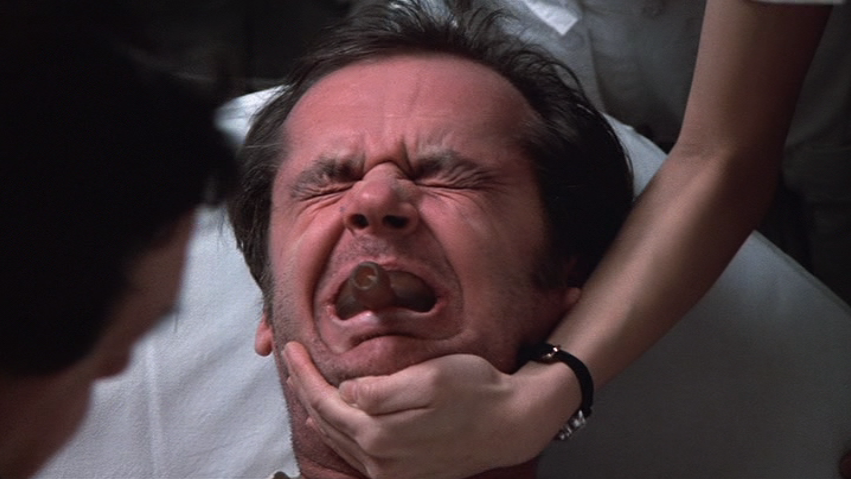

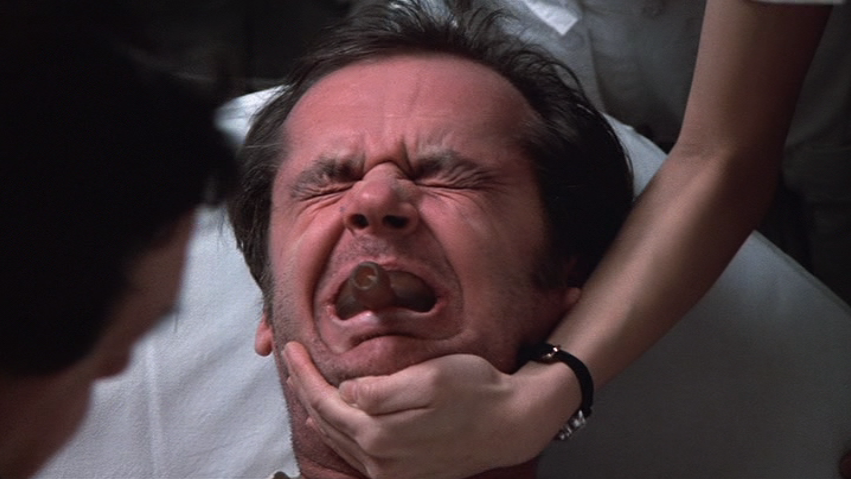

Forman’s unblinking lens (the precise opposite of an unreliable narrator) illustrates the toll this rebellion takes on McMurphy by refusing to cut away. The electroshock therapy scene makes for intensely difficult watching, simply because of how naked it feels. There’s no movie magic here; it’s a man on a gurney, acting out his pain. We don’t get any fake electricity sound effects, we don’t cut to black and leave the audience to imagine things, and we don’t have another character explain to us what the experience is like. Kesey’s depiction of the punishment is entirely internal, relayed through Bromden. Forman’s is entirely external, captured through a camera’s lens. Both of them in perfect keeping with the strengths of their format.

This is McMurphy, writhing in agony, and we are not spared a second. Whatever the strength of his swagger after this scene, from this point on it’s impossible to not be aware of the effect it’s having on him. We’ve seen him at his most vulnerable. We’ve seen how doomed his rebellion really is. It’s something he’ll never reveal to the other patients…but we’ve already seen it.

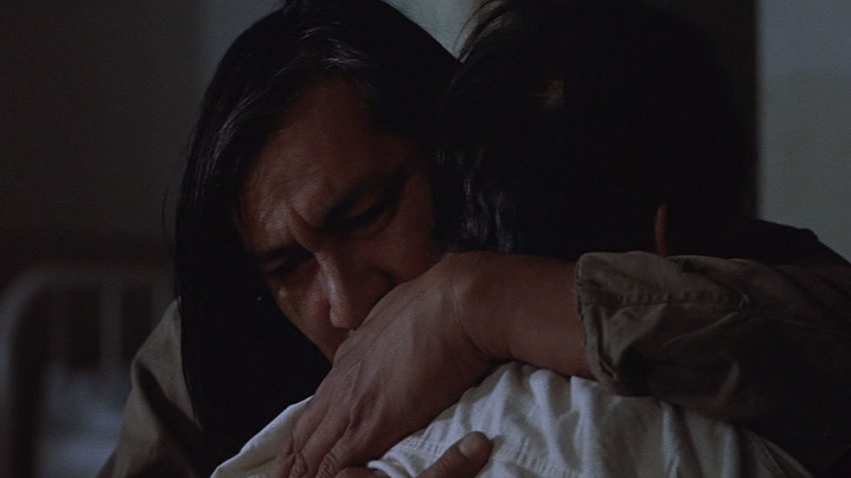

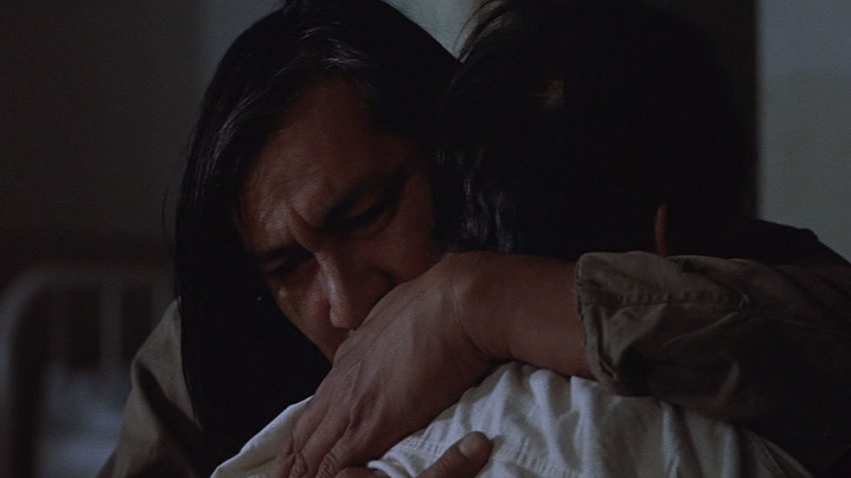

Of course, the electroshock therapy scene is also where we learn that Chief Bromden is neither deaf nor dumb…a significant change considering that we know these things from the very start of the novel.

It’s yet another very interesting effect of sidelining Bromden. What was one of the very first things we learned in the book — one that shaped the way in which every event was reported to the reader — becomes a mid-film surprise. In both cases Bromden speaking represents a major evolution for the character, and is crucial evidence of the positive impact McMurphy is having on his fellow patients. But the film allows us to share McMurphy’s surprise, and his incredible series of reactions to the development.

At first he can’t bring himself to believe that the Chief thanked him for a stick of gum, so he does what any good scientist would do: he offers him another, to see if he can repeat the result. Nicholson’s performance throughout this entire scene is a thing of beauty, starting with the fact the he can’t decide if this is evidence that he’s helping Bromden, or going insane himself.

When Bromden does speak again (“Ah, Juicy Fruit.”) it’s just after McMurphy loses hope, and looks away. At this point Nicholson leaps into a state of elation and laughter, as we likely do in the audience as well.

And this quickly shifts into worry as he remembers where he is. “What are we doing in here, Chief?” he asks, immediately sobered.

Nicholson cycles through this series of emotions flawlessly…and they each feel as though they spring from the previous one naturally. It’s profoundly sad that when he realizes that he has a confidant in the Chief, he opens right up to him. It demonstrates how starved he is for somebody, anybody, that he can communicate with in a significant way.

The surprise of Bromden speaking is probably the most famous moment in this film, apart from — of course — the ending. And it succeeds because of how perfectly, and simply, it balances everything that’s happening in the entire story. The idea of actual vs. feigned mental illness, power rendering its victims helpless, the punishment that’s unfolding in the background and about to engulf them, the psychological retreat of the men, the fleeting smallness of triumph.

It’s an equally powerful moment in both media, but it plays differently in each. Which might actually be the best part about it; if you’ve already experienced it in one version of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, the other still has the capacity to surprise.

This commiseration with the Chief is perhaps the first sign of the toll McMurphy’s rebellion is taking on him, and the electroshock therapy that follows cements it. In the novel, that same toll is relayed in a much different way. There, McMurphy takes a short detour after the fishing trip to show the patients his childhood home. He doesn’t get out of the car…he just tells them stories. He seems to be the same person he always was, except that Chief Bromden catches a glimpse of his face in an expected splash of light, and he sees a tired and hurting man. Bromden sees then what their all-too-human savior is going through.

It’s one of the most significant and important moments in the entire novel…and Forman snips it. That’s not a problem in itself, since — as with most of his snips — it’s in aid of showing rather than telling, and it’s a change that suits the medium. The problem is that Forman doesn’t also snip the fishing trip. Its most important moment has been excised, but the outing is still here…a bloated, uncomfortably silly sequence robbed of its purpose, breaking the sense of suffocation and claustrophobia for no real narrative or artistic gain.

It’s an unfortunate example of flab in an otherwise perfectly constructed film, one which thrives on (and is weakened by any distance from) the central conflict between Nurse Ratched and McMurphy.

The extraordinary tension between the two, even (or especially) when they are both completely silent, makes the film what it is. At no point in their scenes together does one get the sense that we are watching two actors give us a performance; this is real, cold, calculated abuse, and as the story progresses both Kesey and Forman do a great job of ratcheting up the pain, the desperation, and the stakes.

It begins with their very first meeting, a group therapy session on McMurphy’s first day. And we know something is wrong not because the characters tell us, but because they say nothing. Forman catches Nurse Ratched flicking her eyes to her new charge. McMurphy just sits back and observes. Neither of them have any concept of the struggle they’re already locked into, but they both know well enough to size each other up, and identify whatever weaknesses they can. Whether in the prison or the mental institution, they each know the threat that one person with power can wield.

When two actors work well together, it’s often referred to as chemistry. What Fletcher and Nicholson have is something more like toxicity. There’s a genuinely scary, deeply affecting darkness that runs between them from the beginning of the movie through the end. At no point do we or can we suspect that they will come to respect the other’s point of view. There will be no compromise. When it ends, only one of them can remain standing. They both know that, and neither would dare give up the fight.

Throughout everything — the fishing trip, the patients pretending the watch the World Series, the basketball games, the electroshock, the group therapy sessions — this is the conflict that looms. This is the knowledge that is never far from what we are watching unfold before us. Like McMurphy laughing when the Chief thanks him, any joy we feel on the ward is fleeting. We can chuckle at the funny parts and ponder the profound parts, but quickly, sadly, soberly, we remember where we are.

What are we doing in here, Chief?

Several times throughout the course of the film it’s made clear that Nurse Ratched — for all her perceived good — cares more about demonstrating her power than she does about what’s right for the patients. One of these demonstrations comes in the electroshock therapy scene, and it’s more than just the fact that this method of “therapy” is being deployed as punishment.

She sends three patients, after all, for the treatment. Sending McMurphy makes sense; he smashed the window to the nurse’s office and punched one of her orderlies. Sending Bromden, too, makes sense; he participated in the ensuing brawl. But the third patient, poor Cheswick, did nothing. He was neither violent nor uncontrollable; he was voicing his concerns about cigarette rationing in a way that was indeed aggressive, but was by no means deserving — as she well knew — of severe punishment. What he needed was somebody to help him calm down, but she decided instead to us him to make a point: when you enable or support or befriend her enemy, you become her enemy.

A more significant example comes at the end of the film, when she finds Billy Bibbit the morning after the party, having lost his virginity and freed himself of his stutter. She breaks him down, threatening to tell his mother, refusing to give anything in the way of support even as he is dragged screaming down the hallway. She tells her orderlies to lock him in the doctor’s office, alone. Even if he didn’t commit suicide in there, it’d be difficult to find any kind of therapeutic value in her verbal abuse and threats toward the boy.

When Billy takes his own life, a direct result of his treatment at the hands of the Big Nurse, McMurphy snaps. The rage building behind Nicholson’s eyes is a perfect (maybe the perfect) example of why he’s one of the best actors we’ve ever had. He isn’t Jack Nicholson. He’s R. P. McMurphy. An angry dog at the end of his chain, just before breaking free.

We know what’s coming, and Forman’s camera lingers, letting them share the same shot longer than he has before, McMurphy seething while Nurse Ratched must see him, but is unable to process it. She’s in crisis control mode, but it’s for a different crisis.

The camera holds steady until McMurphy breaks, and he takes her by the throat.

Now, Forman’s careful, deliberate shooting instantly and artfully shatters. His was a calm camera. His takes were long. His editing deceptively simple. Everything was carefully blocked and arranged. He was documenting, after all, a ward of order.

Until McMurphy gets both of his hands around order’s neck, and throttles it against the wall.

The camera can’t keep up. Patients keep getting in the way of the shot. There’s not a clear view of what’s happening, at least never for long, but we can feel it. We see it even when we can’t.

He beats her against the wall. He tackles her to the ground. He chokes her long enough that the life begins to leave her, and the camera is as shocked and unable to process all of this as the patients. It, too, seems to have still been reeling from Billy’s suicide. It only just barely manages to catch the next development. And it doesn’t get a chance to breathe until Nurse Ratched does too…as McMurphy is knocked unconscious from behind by one of the orderlies she — literally — could not live without.

In the end, McMurphy is removed from the ward. As in the novel, rumors spread of his escape. As in the novel, he returns after an extended absence. As in the novel, Nurse Ratched has had him lobotomized.

But there a few differences here, and significant ones. Bromden euthanizes him, in both cases so he will not serve as a barely-alive testament to Nurse Ratched’s incontestable authority, and escapes.

In the novel, this happens after McMurphy’s body has already been on the ward for a while, and has been examined and processed by the other patients. In the film, Forman returns McMurphy to his bed in the middle of the night, and Bromden is the only one to encounter him in this vegetative state.

This means that in the novel, in a relative sense at least, Nurse Ratched got what she was after. McMurphy didn’t live long on the ward after his operation, but every minute that he was there registered as a triumph for her. He was a monument to her success.

In the film, she has no such monument. Bromden, heartbreakingly, tells McMurphy that he’s finally ready to escape…and then sees the scars. He’s too late. He hugs McMurphy, or what’s left of him, to his chest. And then he smothers his friend with a pillow.

None of the other patients see McMurphy before he’s killed. In fact, they don’t realize anything is happening until Bromden hurls the control panel through the window and escapes…his final gesture serving as a moment of conflicted triumph in both the book and the film, and the perfect ending to each.

But something happens as Bromden runs away in the film that can’t happen in the book: his fellow patients (Chewsick, Taber, Harding, et al.) watch him go. In the book, those people are all gone for various reasons. Largely, they’ve found the strength to leave the ward. And they do, before McMurphy’s body is ever returned. This is evidence, obviously, of the effect McMurphy had on them. The patients may have been committed voluntarily, but they still could not leave. Thanks to the acts and miracles of McMurphy, they finally do. They sign themselves out, and they don’t look back. Bromden remains because he’s not a voluntary patient…and by the time McMurphy returns, he’s one of the few on the ward who would recognize him.

This makes Bromden’s gesture that much more important in the film. The patients were strong enough to leave before this moment in the novel, but they were still not strong enough to leave in the film. In Forman’s vision, Bromden is the first one out, not the last. His final gesture is as important to the rest of the patients as anything McMurphy did for them, whereas in the novel it’s unlikely that any of them even find out it happened.

Though the Chief’s final decision plays out the same way in both versions, in the novel it’s mainly for him. In the film, it’s for everybody. It’s for everybody left. It’s a final chance for them to act on everything McMurphy had been trying to get them to act on all along.

In the novel, McMurphy succeeded…though he’d never know it. He did convince them that they were no more crazy than anybody on the streets. He did convince them that life was worth living, and that fear was not worth nurturing. He did convince them that there was more to being alive than safety and routine. None of them got the chance to thank him for it, but they all took it to heart…and they all signed themselves out.

In the film, if anyone succeeds, it’s Chief Bromden. The spirit of McMurphy lives on through him…a testament to a friendship deeper than either of them realized it was. It’s an incredible and enduring moment in cinema, and one rendered more important to the other characters by directorial decision, and the simple shifting of narrative perspective.

In the novel, the ending had to be more significant to Bromden, because it was Bromden’s story. In the film, the story belonged to McMurphy, and when he died the ending belonged to everybody.

That’s why it’s so surprising for those who start with the film to find out that Bromden is the novel’s narrator. It means that however similar the two tellings might be, the shift in perspective makes it an entirely different kind of story.

And that’s bound to be at least a little bit of the reaction; the welcome surprise that they’ll get to experience it anew, in a different format, all over again.

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest

(1962, Ken Kesey; 1975, Milos Forman)

Book or film? I genuinely can’t say. Each is a powerful, devastating, nearly-perfect work in its own right. I’d love to hear from somebody in the comments who does prefer one to the other, because I’m unable to view them as anything other than glorious equals. If I must choose for the sake of choosing, though, I’ll go with the book. It’s portable.

Worth reading the book? Definitely.

Worth watching the film? Definitely.

Is it the best possible adaptation? Yes. The casting and performances could not possibly be bettered, and a hypothetical smoothing out of its rougher edges wouldn’t necessarily make for a better film, nor would including a larger sample of the book’s content. It endures for a reason, and it’s hard to imagine a version working better than this already does.

Is it of merit in its own right? It does exactly what an adaptation should do; it preserves the integrity of the source material while making all changes necessary to suit the medium of film. It not only has merit in its own right; it is its own unforgettable, profound, haunting experience, which both enhances and stands entirely apart from the novel.