Friend of the website Dave is hosting a 1990s blogfest today. He’s managed to rope quite a few great bloggers into this (complete list and his own choices here), and we’re also now selling cosmetics door to door on his behalf. The idea is to choose one thing — one anything — as your favorite thing from each year from 1990 – 1999, and write a short bit about it. He also did one for the 2000s, which was pre-Noiseless Chatter I think, but since everything released in that time period was garbage you missed nothing. (And, honestly, I’ll probably end up doing a 2000 – 2010 one just for the heck of it.) Anyway, enjoy…thanks to Dave for hosting this, and let me know what some of your own choices might have been in the comments below. Or tell me I’m wrong in a profane way…I always like that!

1990 – Vineland

I feel more than a little intellectually guilty for only including one novel in my year-by-year rundown, but I’d have to say that the 1990s weren’t particularly well served in a literary sense. Fortunately, though, the decade opens with perhaps the warmest, most welcoming book my favorite author ever wrote. Vineland takes place in 1984, but is very much a love letter to the 1960s. It introduces us to Zoyd Wheeler, a cultural isolate from that lost decade of love, sex and freedom, who’s been reduced to throwing himself through windows to keep up a stream of mental disability checks. It’s an innately comic setup, but the backward, twisting path through time, loss and inevitability is perfectly heartbreaking. Zoyd’s reliable antics, after all, began as an act of genuine desperation when his wife left him, and it’s only been the steady march of time that’s diluted them to meaningless repetitions of what once meant so much. That’s the angle Pynchon takes as he explores the effect aging has had on this world, and ours. It’s Zoyd’s daughter who pulls the narrative along — or backward — as she uncovers, thread by thread, who her mother was. And who her mother became. And, if she learns enough from what she finds, how to avoid a similar fate for herself. Pynchon’s narratives hurdle unfailingly toward doom, but Vineland is the one that reminds you that life is always worth living…regardless of where you might actually end up.

I feel more than a little intellectually guilty for only including one novel in my year-by-year rundown, but I’d have to say that the 1990s weren’t particularly well served in a literary sense. Fortunately, though, the decade opens with perhaps the warmest, most welcoming book my favorite author ever wrote. Vineland takes place in 1984, but is very much a love letter to the 1960s. It introduces us to Zoyd Wheeler, a cultural isolate from that lost decade of love, sex and freedom, who’s been reduced to throwing himself through windows to keep up a stream of mental disability checks. It’s an innately comic setup, but the backward, twisting path through time, loss and inevitability is perfectly heartbreaking. Zoyd’s reliable antics, after all, began as an act of genuine desperation when his wife left him, and it’s only been the steady march of time that’s diluted them to meaningless repetitions of what once meant so much. That’s the angle Pynchon takes as he explores the effect aging has had on this world, and ours. It’s Zoyd’s daughter who pulls the narrative along — or backward — as she uncovers, thread by thread, who her mother was. And who her mother became. And, if she learns enough from what she finds, how to avoid a similar fate for herself. Pynchon’s narratives hurdle unfailingly toward doom, but Vineland is the one that reminds you that life is always worth living…regardless of where you might actually end up.

1991 – A Link to the Past

It’s a fact: the Super Nintendo is the single greatest video game console of all time. Consequently, the early to mid 1990s were a veritable goldmine for gamers. While the NES introduced us to massive numbers of endearing and enduring characters, the SNES took everything at least one step further, and managed to refine and build upon game mechanics without overcomplicating them, or losing sight of what made them work. Super Mario World, Super Metroid and Super Castlevania IV (among so many others) all represented a realization of promise, a step deeper into fantastic and complex universes that we always knew existed just below the surface. But it’s A Link to the Past that really stands out. Taking absolutely everything that worked about the first Zelda game and disposing of everything that didn’t, A Link to the Past laid the precise groundwork for every game in the series that followed, regardless of console. And while certain later entries, such as Majora’s Mask or Wind Waker, attempted to pull the series in other directions, it’s A Link to the Past that rightfully gets the credit for building the solid foundation and framework that gave those later installments the room to expand. The graphics are gorgeous, the music is great, and even if the challenge is somewhat lacking, every new secret you find on the map feels earned and satisfying. I love A Link to the Past. It’s one of perhaps two or three games in the history of the universe that does literally nothing wrong, and it’s a perfect example of what made the SNES so great.

It’s a fact: the Super Nintendo is the single greatest video game console of all time. Consequently, the early to mid 1990s were a veritable goldmine for gamers. While the NES introduced us to massive numbers of endearing and enduring characters, the SNES took everything at least one step further, and managed to refine and build upon game mechanics without overcomplicating them, or losing sight of what made them work. Super Mario World, Super Metroid and Super Castlevania IV (among so many others) all represented a realization of promise, a step deeper into fantastic and complex universes that we always knew existed just below the surface. But it’s A Link to the Past that really stands out. Taking absolutely everything that worked about the first Zelda game and disposing of everything that didn’t, A Link to the Past laid the precise groundwork for every game in the series that followed, regardless of console. And while certain later entries, such as Majora’s Mask or Wind Waker, attempted to pull the series in other directions, it’s A Link to the Past that rightfully gets the credit for building the solid foundation and framework that gave those later installments the room to expand. The graphics are gorgeous, the music is great, and even if the challenge is somewhat lacking, every new secret you find on the map feels earned and satisfying. I love A Link to the Past. It’s one of perhaps two or three games in the history of the universe that does literally nothing wrong, and it’s a perfect example of what made the SNES so great.

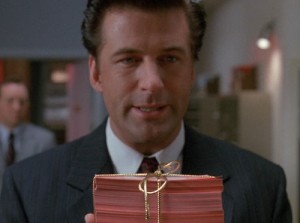

1992 – Glengarry Glen Ross

For a movie with no action, Glengarry Glen Ross is riveting. For a movie with two locations, Glengarry Glen Ross feels enormous. And for a movie with so little at stake, Glengarry Glen Ross feels profound. It’s a story about selling real estate, and how difficult a racket that can be, but it’s also a story about despair, about self-preservation, about pride, about confidence, and about what it means to be a man. It’s all of these things, and it’s more, and the same answer is never given to the same question twice. When a nameless emissary drops by the sales office to address unsatisfactory work, he motivates the sales force by setting them at each other’s throats: the two most successful salesmen will be rewarded to varying degrees, and the other two will lose their jobs. What follows is a single, seemingly-unbroken narrative that spans the rest of that night and the next morning. To say any more than that would likely both give away too much and artificially enhance the importance of anything that happens. The magic — and the story — is all in the dialogue. Glengarry Glen Ross began as a stage play, and it shows. Its big screen adaptation does not seek to overwhelm, astonish, or impress; it seeks to focus. It seeks make you notice every shift of the eye, twitch of the finger, and speck of spittle that accompanies a profane explosion, making it feel like an even smaller and more intimate experience than the play could have ever been. It’s a film that’s terrifying, and it’s terrifying mainly because there’s nothing here to be afraid of. After all, these are just people. Highly and eternally recommended.

For a movie with no action, Glengarry Glen Ross is riveting. For a movie with two locations, Glengarry Glen Ross feels enormous. And for a movie with so little at stake, Glengarry Glen Ross feels profound. It’s a story about selling real estate, and how difficult a racket that can be, but it’s also a story about despair, about self-preservation, about pride, about confidence, and about what it means to be a man. It’s all of these things, and it’s more, and the same answer is never given to the same question twice. When a nameless emissary drops by the sales office to address unsatisfactory work, he motivates the sales force by setting them at each other’s throats: the two most successful salesmen will be rewarded to varying degrees, and the other two will lose their jobs. What follows is a single, seemingly-unbroken narrative that spans the rest of that night and the next morning. To say any more than that would likely both give away too much and artificially enhance the importance of anything that happens. The magic — and the story — is all in the dialogue. Glengarry Glen Ross began as a stage play, and it shows. Its big screen adaptation does not seek to overwhelm, astonish, or impress; it seeks to focus. It seeks make you notice every shift of the eye, twitch of the finger, and speck of spittle that accompanies a profane explosion, making it feel like an even smaller and more intimate experience than the play could have ever been. It’s a film that’s terrifying, and it’s terrifying mainly because there’s nothing here to be afraid of. After all, these are just people. Highly and eternally recommended.

1993 – Mega Man X

I deliberately avoided mentioning Mega Man X when I basked in the glory of the SNES library above, simply so I could single it out here. Mega Man is unquestionably one of my favorite game series ever, and Mega Man X deviates from the classic formula just enough to justify it as a spinoff. With an increased focus on item collection, upgrades and lingering effects of defeated bosses, Mega Man X brought additional levels of non-linearity to an already legendarily non-linear experience. While the series may have gone off the rails after another four or five games (it’s debatable), the original is a stone-cold classic, with great bosses, impressive stages, and gameplay so versatile that fans, almost 20 years later, are still discovering new ways to play it. Mega Man was never about deep plot or engrossing storylines; these were action games through and through. Mega Man X wisely didn’t try to separate itself from the originals by way of an epic storyline…it simply enhanced the action, layered on new and impressive complications, and married it to a stellar soundtrack. Mega Man X is just fantastic.

I deliberately avoided mentioning Mega Man X when I basked in the glory of the SNES library above, simply so I could single it out here. Mega Man is unquestionably one of my favorite game series ever, and Mega Man X deviates from the classic formula just enough to justify it as a spinoff. With an increased focus on item collection, upgrades and lingering effects of defeated bosses, Mega Man X brought additional levels of non-linearity to an already legendarily non-linear experience. While the series may have gone off the rails after another four or five games (it’s debatable), the original is a stone-cold classic, with great bosses, impressive stages, and gameplay so versatile that fans, almost 20 years later, are still discovering new ways to play it. Mega Man was never about deep plot or engrossing storylines; these were action games through and through. Mega Man X wisely didn’t try to separate itself from the originals by way of an epic storyline…it simply enhanced the action, layered on new and impressive complications, and married it to a stellar soundtrack. Mega Man X is just fantastic.

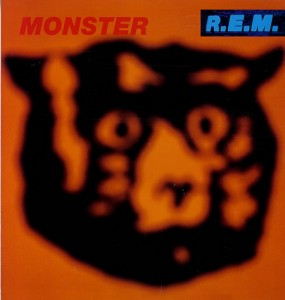

1994 – Monster

So nobody likes Monster. I know that. I also know that that’s their loss. R.E.M.’s hardest rocking album might be so much of a departure from their usual sound that it’s hard to consider it a legitimate installment in their discography…but so what? It’s fantastic. When I listen to Monster — which I do for weeks at a time whenever I stumble across it again — I hear some of the best straight-up rock and roll to come out of the decade. And it’s not entirely devoid of R.E.M.’s signature songwriting, either…you just have to listen through some thrashing guitars to find it. Songs like “Strange Currencies,” “Tongue,” and “Crush With Eyeliner” are all pulled off with the band’s usual sideways insight into the human condition, with all of the disappointment and humane absurdity that implies. The band just happened to couch that insight in some brilliantly distracting, raw, unpolished instrumentation, and that brings with it a charm of its own…a little taste of R.E.M. as the up-and-coming garage band they never were. Some fans are all too eager to dismiss this brief experiment. For me it’s top shelf material, beaten only by Automatic For the People and Lifes Rich Pageant. If you’ve written it off before, it may be worth a reappraisal.

So nobody likes Monster. I know that. I also know that that’s their loss. R.E.M.’s hardest rocking album might be so much of a departure from their usual sound that it’s hard to consider it a legitimate installment in their discography…but so what? It’s fantastic. When I listen to Monster — which I do for weeks at a time whenever I stumble across it again — I hear some of the best straight-up rock and roll to come out of the decade. And it’s not entirely devoid of R.E.M.’s signature songwriting, either…you just have to listen through some thrashing guitars to find it. Songs like “Strange Currencies,” “Tongue,” and “Crush With Eyeliner” are all pulled off with the band’s usual sideways insight into the human condition, with all of the disappointment and humane absurdity that implies. The band just happened to couch that insight in some brilliantly distracting, raw, unpolished instrumentation, and that brings with it a charm of its own…a little taste of R.E.M. as the up-and-coming garage band they never were. Some fans are all too eager to dismiss this brief experiment. For me it’s top shelf material, beaten only by Automatic For the People and Lifes Rich Pageant. If you’ve written it off before, it may be worth a reappraisal.

1995 – “Knowing Me Knowing Yule With Alan Partridge”

I love Alan Partridge. He ranks easily among my five favorite comic creations throughout all of human history, and that’s due in large part to the way that Steve Coogan slips — seemingly effortlessly — into Alan’s skin and becomes him. Though he started behind a sports desk and then moved into the chat-show format, there was always something more to him. He was never a “type,” and the humor was not situational; Alan was a human being, free to be himself wherever — and with whomever — he was. He was a person, a person with insecurities, interests, and a uniquely slanted perspective. “Knowing Me Knowing Yule” is a one-off special that bridges the gap between Knowing Me Knowing You With Alan Partridge and I’m Alan Partridge…two very different, but perfectly complementary, insights into this fascinating man. It’s presented as a needlessly expensive and woefully inessential yuletide installment of Alan’s chat show, and it’s what seals the casket on his broadcasting career forever. Considering that the last proper episode of Alan’s chat show saw him shooting a guest through the heart live on air, that gives you an idea of just how poorly this festive outing manages to go. It’s a great and always welcome entry into the Christmas special canon, and worth a watch at least once per year. Alan getting threatened by a transvestite, failing to properly lip-synch “The 12 Days of Christmas” and struggling desperately to halt an in-process bit of product placement never gets old. Watch it during a family gathering. Believe me, it will make you feel better about everyone you’re related to.

I love Alan Partridge. He ranks easily among my five favorite comic creations throughout all of human history, and that’s due in large part to the way that Steve Coogan slips — seemingly effortlessly — into Alan’s skin and becomes him. Though he started behind a sports desk and then moved into the chat-show format, there was always something more to him. He was never a “type,” and the humor was not situational; Alan was a human being, free to be himself wherever — and with whomever — he was. He was a person, a person with insecurities, interests, and a uniquely slanted perspective. “Knowing Me Knowing Yule” is a one-off special that bridges the gap between Knowing Me Knowing You With Alan Partridge and I’m Alan Partridge…two very different, but perfectly complementary, insights into this fascinating man. It’s presented as a needlessly expensive and woefully inessential yuletide installment of Alan’s chat show, and it’s what seals the casket on his broadcasting career forever. Considering that the last proper episode of Alan’s chat show saw him shooting a guest through the heart live on air, that gives you an idea of just how poorly this festive outing manages to go. It’s a great and always welcome entry into the Christmas special canon, and worth a watch at least once per year. Alan getting threatened by a transvestite, failing to properly lip-synch “The 12 Days of Christmas” and struggling desperately to halt an in-process bit of product placement never gets old. Watch it during a family gathering. Believe me, it will make you feel better about everyone you’re related to.

1996 – “22 Short Films About Springfield”

Coming at a time when The Simpsons could genuinely do no wrong, “22 Short Films About Springfield” reads like a time-capsule today. It’s a relic — and a loving, fascinating, and clever one — of a time when Springfield was more than just a sea of caricatures and types; it was a place, fully functional in and of itself. One operating under its own logic and impossible to mistake for the real world, but real in its own way all the same. It’s a half hour without plot, without intention, and without a moral…just a simple, and undoubtedly well-earned, chance to take a deep breath and survey the incredible playground the show had built up for itself by that point. The characters were so well established and the dynamics between them so fruitful that all you needed to do was let Apu take some time off, bring Reverend Lovejoy and his dog to Flanders’ front lawn, or give a stranger the chance to turn the tables on Nelson, and comedy would flow. Effortless, wonderful, eternal comedy. “22 Short Films About Springfield” floats by like a whisper, as it should. While any other show on television could work harder and harder every week to make even a fraction of the impact on the cultural landscape that The Simpsons made, The Simpsons itself didn’t seem to need to work at all. It could just step back and see what the characters were doing…and, here, that’s what it did. The Skinner / Chalmers segment will go down in history as an all-time best sequence no matter how long the show runs, but even if that clear highlight were to be somehow excised from the episode, “22 Short Films About Springfield” would still be a perfect gem. With so many forgettable seasons behind us now, the episode is almost like footage of a great civilization long gone: those of us that were there will always have this souvenir, and those who missed it will be eternally grateful for this brief — and brilliant — window into the past.

Coming at a time when The Simpsons could genuinely do no wrong, “22 Short Films About Springfield” reads like a time-capsule today. It’s a relic — and a loving, fascinating, and clever one — of a time when Springfield was more than just a sea of caricatures and types; it was a place, fully functional in and of itself. One operating under its own logic and impossible to mistake for the real world, but real in its own way all the same. It’s a half hour without plot, without intention, and without a moral…just a simple, and undoubtedly well-earned, chance to take a deep breath and survey the incredible playground the show had built up for itself by that point. The characters were so well established and the dynamics between them so fruitful that all you needed to do was let Apu take some time off, bring Reverend Lovejoy and his dog to Flanders’ front lawn, or give a stranger the chance to turn the tables on Nelson, and comedy would flow. Effortless, wonderful, eternal comedy. “22 Short Films About Springfield” floats by like a whisper, as it should. While any other show on television could work harder and harder every week to make even a fraction of the impact on the cultural landscape that The Simpsons made, The Simpsons itself didn’t seem to need to work at all. It could just step back and see what the characters were doing…and, here, that’s what it did. The Skinner / Chalmers segment will go down in history as an all-time best sequence no matter how long the show runs, but even if that clear highlight were to be somehow excised from the episode, “22 Short Films About Springfield” would still be a perfect gem. With so many forgettable seasons behind us now, the episode is almost like footage of a great civilization long gone: those of us that were there will always have this souvenir, and those who missed it will be eternally grateful for this brief — and brilliant — window into the past.

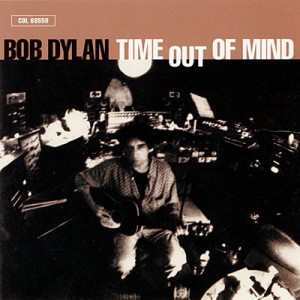

1997 – Time Out of Mind

I’ve talked a bit about Dylan’s lost years here, but I didn’t say much about what brought him back to life. Time Out of Mind is what brought him back to life. For me, it was released at the perfect time; just as I started to explore Dylan myself, this came out. Suddenly the warnings to avoid “the recent stuff” went quiet…and I do mean suddenly. Time Out of Mind is a bullet of an album…a shot through the brain that lingers and haunts and does not let go, and critics and fans alike flocked to it immediately. Time Out of Mind doesn’t feel like a comeback album…it feels like he never left. Though his youthful, nasal prophesying is replaced here by a gravelly howl, it’s Dylan to the core, providing one of his best love songs (“Make You Feel My Love”), some chillingly vague danger (“Cold Irons Bound”), and a classic meandering tale of introspection, playing Neil Young at high volumes, and ordering hard-boiled eggs at a restaurant (“Highlands”)…it’s a gloriously meandering shaggy-dog story that caps off an aimless-by-design rediscovery of who Dylan is. It would be quicker to list the things I don’t like about this album, because there really aren’t any. Songs like “Tryin’ to Get to Heaven” and the bluntly desolate “Not Dark Yet” triggered suspicions that this was Dylan’s final statement…that the man had pulled it together one last time, to end his career on a high note. He’s released four more albums of new material since then. Dylan’s going out on a high note alright…he’s just making sure to sustain it this time. On his next album, Dylan would sing “You can always come back, but you can’t come back all the way.” That would have made more sense before Time Out of Mind, which disproves it conclusively.

I’ve talked a bit about Dylan’s lost years here, but I didn’t say much about what brought him back to life. Time Out of Mind is what brought him back to life. For me, it was released at the perfect time; just as I started to explore Dylan myself, this came out. Suddenly the warnings to avoid “the recent stuff” went quiet…and I do mean suddenly. Time Out of Mind is a bullet of an album…a shot through the brain that lingers and haunts and does not let go, and critics and fans alike flocked to it immediately. Time Out of Mind doesn’t feel like a comeback album…it feels like he never left. Though his youthful, nasal prophesying is replaced here by a gravelly howl, it’s Dylan to the core, providing one of his best love songs (“Make You Feel My Love”), some chillingly vague danger (“Cold Irons Bound”), and a classic meandering tale of introspection, playing Neil Young at high volumes, and ordering hard-boiled eggs at a restaurant (“Highlands”)…it’s a gloriously meandering shaggy-dog story that caps off an aimless-by-design rediscovery of who Dylan is. It would be quicker to list the things I don’t like about this album, because there really aren’t any. Songs like “Tryin’ to Get to Heaven” and the bluntly desolate “Not Dark Yet” triggered suspicions that this was Dylan’s final statement…that the man had pulled it together one last time, to end his career on a high note. He’s released four more albums of new material since then. Dylan’s going out on a high note alright…he’s just making sure to sustain it this time. On his next album, Dylan would sing “You can always come back, but you can’t come back all the way.” That would have made more sense before Time Out of Mind, which disproves it conclusively.

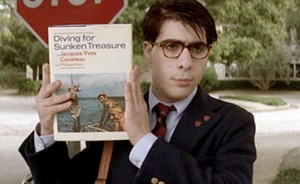

1998 – Rushmore

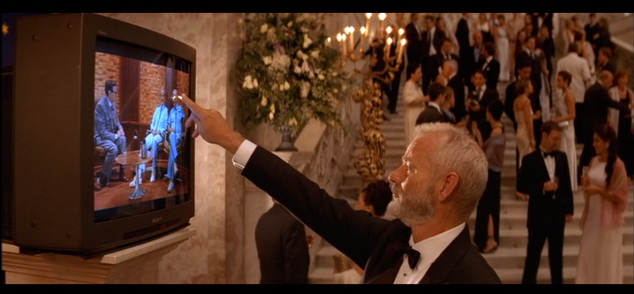

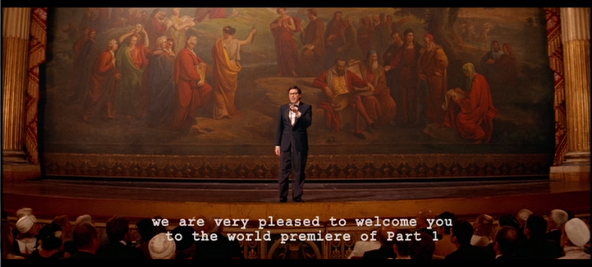

There may not be much more I can say about Rushmore than what I’ve already said here, but that by no means dampens my excitement for talking about it yet again. Rushmore is, by many accounts, Wes Anderson’s best film. Anyone who says that to you, however, is lying. What it is, however, is Wes Anderson’s mission statement, and it’s a solid, fantastic, indelible one. Coming off of Bottle Rocket, Rushmore represents an almost unprecedented stylistic and qualitative step forward. It’s not a film in which Anderson finds his voice…it’s a film in which we find Anderson’s voice. The soundtrack, the costumes, the visual design, the character dynamics, the relentless attention to detail…everything here established what it meant to be “classic Anderson,” and it both defined a career and forever cemented a fanbase. It also introduced the world to Jason Schwartzman, and reintroduced the world to a penitent Bill Murray…a gift to humanity that Anderson should always be praised for. It’s one of those movies packed so densely that no two viewings have to feel the same, and there’s literally always something new to notice, tucked away in the corner of a quick shot, or hiding in plain sight while the camera dwells and your eyes wander. Rushmore is a great film, and while I enjoy it most for what it allowed Anderson to do down the line, I can never watch this one without coming away impressed all over again. And crying when Max introduces Mr. Blume to his father. Because that part’s fucking gold.

There may not be much more I can say about Rushmore than what I’ve already said here, but that by no means dampens my excitement for talking about it yet again. Rushmore is, by many accounts, Wes Anderson’s best film. Anyone who says that to you, however, is lying. What it is, however, is Wes Anderson’s mission statement, and it’s a solid, fantastic, indelible one. Coming off of Bottle Rocket, Rushmore represents an almost unprecedented stylistic and qualitative step forward. It’s not a film in which Anderson finds his voice…it’s a film in which we find Anderson’s voice. The soundtrack, the costumes, the visual design, the character dynamics, the relentless attention to detail…everything here established what it meant to be “classic Anderson,” and it both defined a career and forever cemented a fanbase. It also introduced the world to Jason Schwartzman, and reintroduced the world to a penitent Bill Murray…a gift to humanity that Anderson should always be praised for. It’s one of those movies packed so densely that no two viewings have to feel the same, and there’s literally always something new to notice, tucked away in the corner of a quick shot, or hiding in plain sight while the camera dwells and your eyes wander. Rushmore is a great film, and while I enjoy it most for what it allowed Anderson to do down the line, I can never watch this one without coming away impressed all over again. And crying when Max introduces Mr. Blume to his father. Because that part’s fucking gold.

1999 – “Space Pilot 3000”

When Futurama debuted, it seemed like it was just going to be the less-deserving little brother of The Simpsons. But arriving, as it did, just at the time the elder show was losing steam, it established itself immediately as a more than worthy successor. While The Simpsons took a few seasons to establish a flow and sustainable gag-rate for itself, Futurama burgled some writers and hijacked that momentum, allowing it to fire on all cylinders right from the get-go. The result is an almost impossibly strong first season, kicked off by one of the most confident and well-handled pilots I’ve ever seen. Space Pilot 3000 has barely aged at all. While the voice actors may have still been getting a handle on things, the writing is sharp and solid, and the groundwork for countless fantastic episodes of smart science-fiction, piercing comedy and genuine emotion is laid here. There’s a long love letter to Futurama that I’d like to write, but as the years go by it keeps getting longer…eventually I’d just end up with too much to say. After all, what can I say to a show that gave me “Jurassic Bark,” “Time Keeps On Slipping,” “The Luck of the Fryrish,” “Godfellas,” “Lethal Inspection,” and so many others I love beyond words? Futurama is by no means a perfect show, but for some silly cartoon knockoff of another silly cartoon, it sure managed to exceed expectations quickly. It brought an end to the 90s, but ushered in a whole new expanse of grand adventures and brainy plotwork. Philip J Fry inadvertently froze himself, and woke up in a far stronger television landscape. Welcome to the world of tomorrow.

When Futurama debuted, it seemed like it was just going to be the less-deserving little brother of The Simpsons. But arriving, as it did, just at the time the elder show was losing steam, it established itself immediately as a more than worthy successor. While The Simpsons took a few seasons to establish a flow and sustainable gag-rate for itself, Futurama burgled some writers and hijacked that momentum, allowing it to fire on all cylinders right from the get-go. The result is an almost impossibly strong first season, kicked off by one of the most confident and well-handled pilots I’ve ever seen. Space Pilot 3000 has barely aged at all. While the voice actors may have still been getting a handle on things, the writing is sharp and solid, and the groundwork for countless fantastic episodes of smart science-fiction, piercing comedy and genuine emotion is laid here. There’s a long love letter to Futurama that I’d like to write, but as the years go by it keeps getting longer…eventually I’d just end up with too much to say. After all, what can I say to a show that gave me “Jurassic Bark,” “Time Keeps On Slipping,” “The Luck of the Fryrish,” “Godfellas,” “Lethal Inspection,” and so many others I love beyond words? Futurama is by no means a perfect show, but for some silly cartoon knockoff of another silly cartoon, it sure managed to exceed expectations quickly. It brought an end to the 90s, but ushered in a whole new expanse of grand adventures and brainy plotwork. Philip J Fry inadvertently froze himself, and woke up in a far stronger television landscape. Welcome to the world of tomorrow.