As you know, I’ve been reviewing self-published books on this blog recently. As you also know, I’m currently writing a novel of my own. So allow me to pass down something that’s done me a great deal of creative good.

As you know, I’ve been reviewing self-published books on this blog recently. As you also know, I’m currently writing a novel of my own. So allow me to pass down something that’s done me a great deal of creative good.

Here’s the single hardest lesson I had to learn as a writer. Are you ready? It’s a pretty brutal one:

I sound ridiculous.

And guess what? So do you.

We all sound ridiculous…at least by default. That’s why literature, in all of its forms, has evolved a set of conventions. Romance, comedy, tragedy, mystery, memoir…anything you read will have associated with it a whole host of expectations. Conventions exist for a reason, and that reason is this: they double as the contract between author and audience.

When you read a piece of literature, it’s often fun to point out the tropes and conventions as you go. If you’re especially well-read in a particular genre you might even be able to map out what’s likely to happen next. The big mistake we all make is to surrender to a sort of cynicism that implies this to be a bad thing. It isn’t.*

Conventions exist because people like to know what they are reading. It’s similar to ordering meals in a restaurant…you like to have some sense of what it contains. You don’t necessarily need to know exactly how much of what is in it, or how it was brought together, or how it’s going to taste…but it’s not out of line to want some knowledge of what you’re about to eat. After all…you’ve been eating for your whole life. You know that there are certain things you simply don’t enjoy, and other things you enjoy very much.

When writing, those unspoken conventions serve the same purpose. We should be able to know if mysteries, on the whole, appeal to us without having to read every single one of them. Some will be better than others, sure, but that’s a given. We know that, and conventions don’t at all suggest anything in a qualitative sense. What they do tell us is a list of the ingredients the work is likely to contain. For instance, maybe you read Raymond Chandler and didn’t like the terseness of his writing. In that case, you may simply not be a Chandler fan. However if you read some Raymond Chandler and didn’t like the violence, the red herrings, the alternating seduction and cruelty, or the seemingly silly pursuit of some relatively minor object, then you can pretty much count on the fact that you don’t enjoy detective fiction.

That’s fine. That’s why those conventions exist. Those of us who like it know where to find it, and those who don’t know to look elsewhere.

They also exist in order to give writers direction. The greatest literary artists know how to elasticize them, distort them, give them new and interesting ways to work, but, ultimately, they are there, and they function as signposts. The author may then choose to pull toward those sign posts, to loop mischievously around them, or to deliberately drift as far from them as possible. In any case, they are still there…and if they weren’t, we wouldn’t be able to appreciate what the artist is doing.

You — yes, you, if you intend to write — need to understand this, because it’s what’s going to keep you from sounding ridiculous. These structures and conventions and signposts exist, all of them, explicitly so that you won’t sound like a fool. Because if you just allow yourself to write, without being well-versed in the conventions and expectations of your genre of choice…that’s exactly what you will sound like.

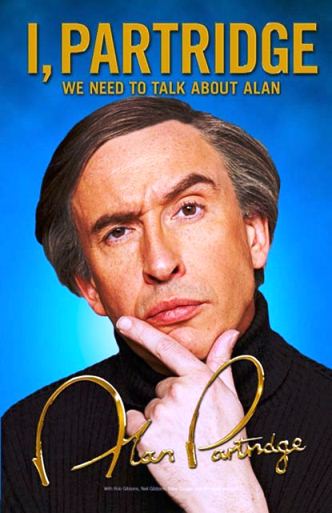

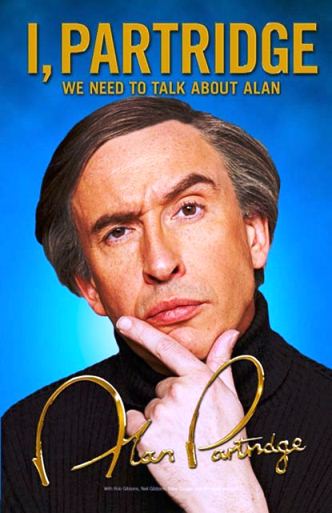

I, Partridge is the rarest of all possible comedy tie-in books: it’s the comedy tie-in book that is also, front to back, a work of art.

It’s the ostensible memoir of Alan Partridge, a fictional character who has appeared in multiple British television and radio programs, as well as stage shows, specials, and pretty much everything else. I, Partridge is that character, recounting his life experiences. And it’s a brilliant work of incredible unreliability.

Granted, if you’ve seen and heard Partridge’s earlier misadventures then I, Partridge doesn’t have to work quite as hard. You’ve seen him shove a piece of cheese into a BBC superior’s face and use the hand of a dead man to sign a contract that would put him back on television, so when Alan narrates these events differently, you understand very clearly the humorous disconnect.

However I don’t think you have to have seen any of that in order to enjoy — and as a writer learn from — the book. It functions within its own reality brilliantly, with Alan’s suspiciously too-careful recitation of details giving away the fact that something is being clearly fabricated.

Throughout the book he misunderstands social cues and signals that the readers pick up on, leaving his narration and the reader’s experience of that narration to diverge wonderfully. Alan continues down a road of doubled self-delusion (as he certainly believes that his readers are taking his lies as gospel) while we are able to parse and inspect the text in order to determine just how far from reality his narration really is.

It’s every bit as fascinating as anything Nabokov — the unrivaled master of unreliable narration — has ever done, but is infinitely more accessible. And for that reason, I think I, Partridge should be required reading for anyone who believes themselves to be a writer.

Alan’s ridiculousness is palpable, and it’s palpable simply because he believes he’s being anything but ridiculous. He couldn’t begin to entertain the fact that anything he’s saying would be suspect…and that’s exactly why it’s so suspicious. His readers stop paying attention to what he says, and start paying attention to how he says it.

Your readers will do the same thing. Because you sound ridiculous.

When reading A Soul’s Calling, there was a similar disconnect. Scott Bishop — or his textual avatar — fancied himself an educated, spiritual humanitarian…but he came across on the page as a foolish, selfish weirdo. When he says that demonic spirits interfere with his life and make people dislike him, he believes it…yet the narration diverges from the experience of the reader, who sees instead that people dislike him because he’s an actively insufferable human being. And when he — in an act of paramount dickishness — finds a prayer note left at base camp by a woman before him, he burns it instead of leaving it under the rock where she left it. Why? Because he knows how this prayer needs to be handled, and she obviously didn’t. In his mind, he did her a favor. Any reader in their right mind, however, would see this as a tremendously rude gesture, and the anonymous woman would be no less hurt by it than Scott himself would be if someone came along and kicked over his pyre because they personally didn’t think that was the right way to pray either.

Similarly, when Lawrence Fisher positions himself as an unfortunate misfit wrestling with the game of love, we as readers see clearly that he’s not alone…literally every woman he dates, whether or not that date goes well, is in the exact same situation, meaning it’s a bit harsh for him to expect us to both feel bad for him and laugh at them when he says they’re annoying, not pretty enough, or just plain undateable. Lawrence wants us on his side as narrator, but he spends so much time pushing away those who are already on his side that we end up distanced as well.

What’s more, he keeps distracting himself from his ostensible topic to quote irreverently from films and television shows, or discuss historical intricacies of his religion, or wonder how people can be rude enough to speak through BlueTooth headsets in a restaurant. There’s nothing wrong with that, but the book is only around 130 pages and he’s spent so much time on tangents that he’s left himself no room to getting around to his actual topic.

What writers need to learn, whether they intend to employ the method or not, is how unreliable narration works. And they need to learn that lest they start narrating unreliably against their will.

I, Partridge features exactly the same failings as the two self-published books I mention above, but with a difference: here, they are failings by design.

Alan assumes the applause for a crippled veteran are directed at himself, a low-level radio personality. He gets lost discussing technical details about headsets and cars and radio frequencies when he’s meant to be relaying interesting anecdotes about important people in his life. His “big breaks” for other up-and-coming performers typically leave them embarrassed, disgraced, and broke.

But Alan doesn’t realize any of this. He is the central comic figure in his own farce, but sees himself as a hero, overcoming tragedy after trial. He uses his complete command over his own memoir to rewrite history, and to paint himself in colors he could never achieve in real life.

Writers do that all the time. And that’s okay.

But they need to do it deliberately, and they need to do it well.

Because if they don’t, they’re just writing their own unintentional comedies.

It doesn’t take much to turn your heart-warming tale of spiritual awakening into a showcase for self-importance and silliness. It’s just a shift in perspective…and it’s the shift in perspective that comes automatically from giving yourself an audience.

I honestly would recommend I, Partridge to anyone who wants to be taken seriously, because the absolute best first step on that road is to see, first-hand, why nobody would.

—–

* At least, it isn’t automatically a bad thing. If that’s all an author is doing, then that’s bad. But an author who uses convention as a framework upon which to build his or her unique story around it is simply doing his or her job as a writer. Railing against convention for the sake of railing against convention is something else many writers find it difficult to grow out of. But mark my words: the longer you spend fighting the form, the more you’re postponing the moment when you learn how to make the form work for you. In short, you’re delaying your own creative growth. So don’t do that.

Here’s a public service announcement: stop waving people on, asshole.

Here’s a public service announcement: stop waving people on, asshole.