How do you solve a problem like the Ochmoneks?

Before we watch the episode struggle to answer that, it’s worth reminding ourselves that as much as I’ve griped about its many (many) problems, ALF has at least managed to acknowledge and correct some of its issues. A great example of this is the relationship that developed between ALF and Lynn last season, repositioning the two of them as friends that share a special, honest bond. Another is the introduction of Jake, which was a solution to the problem of the writers not wanting to do anything with Brian (apparently) but still wanting a young boy around. It was by no means a clean solution, but it shows that they were aware of an issue and took some kind of action to correct it.

This week we attempt to address a different problem, whether the show is conscious of it or not: the Ochmoneks.

Originally introduced as a pair of annoying neighbors, they’ve managed to flesh themselves out and develop more character than literally anybody else in this entire show. Mr. Ochmonek, in particular, established himself as more than just an add-on for his wife. It isn’t just me that appreciates what Jack LaMotta brings to his thankless role; the writers must appreciate it as well, because they’ve given him so much more to do that he’s eclipsed Liz Sheridan significantly in terms of screen time.

The “problem,” then, is more of a question: when the sideshow is more interesting than the main attraction, what do you do?

It’s been observed in the comments here that this show would be better if ALF had crashed into the Ochmoneks’ garage instead. I agree. And yet…he didn’t. So what does ALF do instead? We’ll find out in the following half hour that it really has no idea.

Anyway, let’s take a step back. I’m noticing that ALF is wearing clothes a lot more this season. Toward the end of season one we saw ALF in a Hawaiian shirt, which brought back a lot of memories for me. Though it was an exception to the naked norm, it was perfectly in line with what I remember of ALF’s merchandise.

For whatever reason, ALF toys almost always featured him wearing clothes. It’s strange to me, because he so rarely does. (Or…did?) It would be like seeing a bunch of Yogi Bear dolls on the shelf, each of them dressed as a firefighter. I don’t know…maybe it happened once in the cartoon or something, but it would just feel wrong. Yogi gets a hat and a necktie, and that’s it. Anything else and…he’s not Yogi.

With ALF, though, he was nearly always portrayed outside of the show wearing some kind of outfit. Sometimes it was just an unremarkable Hawaiian shirt, and other times it was a fully recognizable costume, such as a chef or Bruce Springsteen. Why? Why was that ALF?

I wonder if the increased frequency of apparel in this season has anything to do with merchandising. It’s not likely to be a standards and practices thing…after all, ALF had already been naked for two full seasons by this point. Additionally, puppets and cartoons are exempt from nudity concerns unless they have recognizable genitalia. (For the record, when I woke up this morning I never expected to type that sentence.)

I think it’s more of a chance to get people (okay…kids) in the habit of seeing the character in costume, so that the dolls and toys wouldn’t seem less like the “real” ALF. Consequently, they’d sell more.

That’s my best guess, anyway. Prior to this season, nearly any time we saw him in an outfit it was for story reasons, or because they were using that bright orange “backup” ALF puppet that I’m positive only wore clothes because they were hiding some kind of damage.

Speaking of which, maybe putting both puppets in clothes regularly is meant to keep us from noticing when they switch them out.

My main point here is that I don’t want to talk about what’s actually happening.

…but I guess I have to. It’s breakfast time, and ALF wants all the ham and eggs. Kate says, “No, ALF, you live in this house with like a million other people and we have to fucking eat, too. In fact, the only reason I’m serving you first is so you can sneeze into the pan and ruin breakfast for everyone, so stop your shitty bastard bitching for cunt’s sake.”

Then ALF sneezes into the pan and ruins breakfast for everyone.

Honestly, I can’t even tell if ALF did this on purpose. He’s enough of a dick that he would, but I guess he could also have sneezed coincidentally as he was being told that he couldn’t eat everyone’s food. It’s rare that a show is so poorly written that three seasons in you still don’t know if the main character is an asshole or an idiot.

After ensuring that he’s ruined these people’s mornings in addition to their whole lives, he gobbles up a plate of snot covered eggs, daring the audience to come to terms with the things they’ve chosen to fill their time watching.

We get a shot of Benji Gregory saying something I couldn’t hear because I was laughing at the eggs all over him. This poor kid still has nothing to do with anything that happens in the show, but he had to sit still while stage hands covered him in cold, runny eggs before he delivered his single line.

There’s something perfectly terrible about that. I love it, because I’m a heartless human being.

Then Jake comes over and ALF calls him “Jake Your Booty.” I don’t love that at all for any reason.

Apparently the Ochmoneks have been fighting and they resent each other and blah blah fuck you. It smacks of plot manufacture, especially since they’re the only couple on this show that I’ve ever believed are in love. Yes, they’ve got their problems, and I certainly wouldn’t fix either of them up with anybody I know, but they fit together. The things that most people would consider problematic, they seem to find attractive. And in a genuinely satisfying way, that’s sweet.

I know people go through rough times no matter how strong their relationships are, but this is turmoil for the sake of turmoil. If you don’t think that the Ochmoneks fighting represents a stretch of credibility, then you’ll certainly be swayed when you realize that Jake comes to the Tanner house of all places to get away from familial dysfunction.

That smell, my friends, is bullshit.

We come back after the intro credits to the same conversation in the kitchen, making me think it was originally written as one long scene and was hacked up to give the episode a cold open at a later point. Who knows what the original cold open would have been. Probably something hilarious, like ALF bashing Willie’s skull in with a 9-iron.

I don’t really care that they split the scene that way, but if they were going to plop the credits into the middle of it, I’m surprised they didn’t do it after Mr. Ochmonek walked in and they agreed to let him stay with them. That seems like a perfect stopping point, and the scene basically ends there anyway. But, whatever. I’m thinking about things again. I promise I’ll stop.

ALF hides under the table and stabs his family members in the legs with a fork whenever it sounds like one of them might let Mr. Ochmonek stay over. It’s a kind of annoying detour, and it’s not quite worth it for the fact that it ends with Kate kicking ALF in the fucking face. On the bright side, it does end with Kate kicking ALF in the fucking face.

Anyway, Mr. Ochmonek almost eats the booger eggs but then doesn’t. ha ha?

Later, Willie helps him bring his stuff into the Tanner house, and he gets all pissy that Mr. Ochmonek might have to stay with them for more than one night. The guy’s marriage is failing, Willie. I don’t think you telling him to hurry it up is very productive.

Way to social work, asshole.

I know I’ve dug into this before, but I honestly can’t get over it. Why is Willie a social worker? This is a sitcom. That is to say, this is an invented reality. The writers can make him anything at all. Why choose social work if the character doesn’t fit the profile and has no interest in it?

Make him a lab technician, or a librarian. Or an engineer. (Either kind.) Something that would help to develop character rather than work against literally everything we see him do and hear him say.

Once again, this could work if it were the joke. Plenty of sitcom characters are bad at their jobs, or hate their jobs, but we keep getting told that Willie Tanner is the kindest, bravest, warmest, most wonderful human being we’ve ever known in our lives. He’s some kind of social work savant, one who is so valuable and irreplaceable that he deserves raises and promotions showered on him even after he’s caught kidnapping a Mexican kid.

Come on. If Willie’s even 1/1,000th the social worker we’re told he is, he’s surely dealt with countless people who’ve gone through nasty breakups and / or been thrown out with no place to go.

Yet, as we see here, he somehow hasn’t actually learned anything about getting these folks back on track. Unless “I don’t care what you do, but make it snappy” solves more social ills than I’m compelled to believe it does.

Anyway the whole family bitches about how they’ll need to figure out sleeping arrangements while the recently separated Mr. Ochmonek is in the same room. So, that’s another thing good social work entails: making the victim feel as guilty as possible about the inconvenience they’ve now become.

Jake volunteers to sleep with Lynn. It’s funny because he will stick things in her while she is sleeping.

Why is he spending the night, exactly? Did his marriage to Mrs. Ochmonek fall through as well? What the fuck am I watching?

The next morning Willie and Kate come into the kitchen to find Mr. Ochmonek sitting in the middle of a big mess.

I have to admit, this kind of pissed me off. I was afraid that this was going to be how the show solved the problem of the Ochmoneks being more likeable: we’d get an episode that made a point of saying to the audience, “Look! These people really are trash! All those times you thought Willie was the dickblossom, but it was really the fat, bald, ugly guy like we told you! And his wife’s a bitch!”

Instead, thank Christ, it goes in a better direction. ALF wrecked the kitchen in a feeding frenzy overnight. Mr. Ochmonek had nothing to do with it, and just saw the mess when he came in to eat breakfast.

A few nice things happen in this scene. Firstly, Mr. Ochmonek refers to his little stereo as a “suburb blaster,” which is such a perfect line for him in so many ways. You know, the plot of this episode is rekindling my illogical wish that he and Kate will run off together and star in a much better sitcom than this one.

The other thing I like is that Mr. Ochmonek apologizes for using the last of the milk, and volunteers to go borrow some from Mrs. Bird. That’s Iola from the two part episode “Hostage-O.” Hold on to your butts, folks, because ALF just foreshadowed something that never actually happens. Stay tuned!

Mr. Ochmonek, once again, proves himself to be the nicest human being in this entire terrible universe. It’s first thing in the morning and these assholes were not quiet about their preference that he sleep in the compost heap, but he offers to go out and get them milk. By contrast, how many stars would have to align for Willie to loan the guy a quarter to call 911 if he was being actively murdered?

Willie takes the fall for the mess, which is pretty dumb but who cares. Then Lynn and Brian come in, and the difference in acting ability hits you like a brick. Andrea Elson stops dead in her tracks and looks around before speaking, taking in what she’s seeing and making sure she doesn’t misspeak. Benji Gregory, by contrast, just strolls in and sits down as though it’s only another morning.

Again, that would be fine if it were part of the joke, but it’s clearly not. The stage direction was to come in and sit down, so Benji Gregory does exactly that. Just as Max Wright would have. Andrea Elson, I’m positive, was given the exact same stage direction, but put some thought into the context and reacted appropriately. Just as Anne Schedeen would have. I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: I’m glad she takes after her mother.

There’s also one really odd bit when Kate and Willie first walk in. Mr. Ochmonek is listening to his suburb blaster, and it’s playing some generic three-chord rock music. He turns it off and says it was his and Raquel’s favorite song, and then says, “That Sinatra sure could sing.”

The audience laughs, of course, because it sounded nothing like Sinatra. Then Willie says it sounded more like Pink Floyd, and Mr. Ochmonek says it was, the Sinatra comment wasn’t related. It’s funny enough.

But there’s a problem: that also didn’t sound anything like Pink Floyd. I have no idea what it was, but I’ll bet a dollar to donuts it’s just some no-name library garbage. You can’t make a joke about the song sounding nothing like Sinatra, and then try to convince us that it’s Pink Floyd when it sounds no more like them.

I understand that licensing a Pink Floyd song for the purposes of this throwaway joke would be ridiculous, but then maybe we don’t need the joke? Or maybe Willie could reference a different band that actually did sound something like what we were hearing?

The script said Pink Floyd, but whomever chose the track dug up something that sounded nothing like them. As usual, the script says one thing, the props department or producer or someone does something different, and nobody — from the writers all the way down to the actors — alters their work to reflect the change. For a show that took an average of six hundred zillion hours to record every episode, I’m gobsmacked at just how little effort seems to have been put into it.

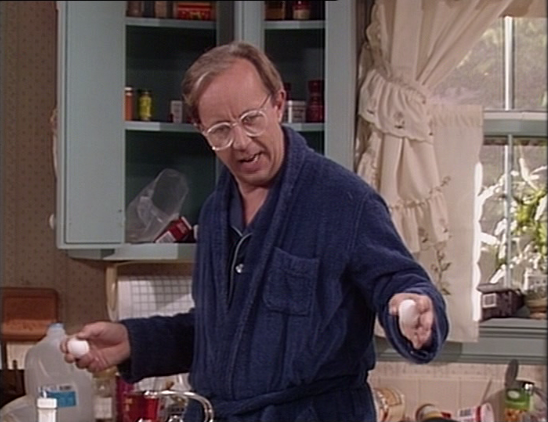

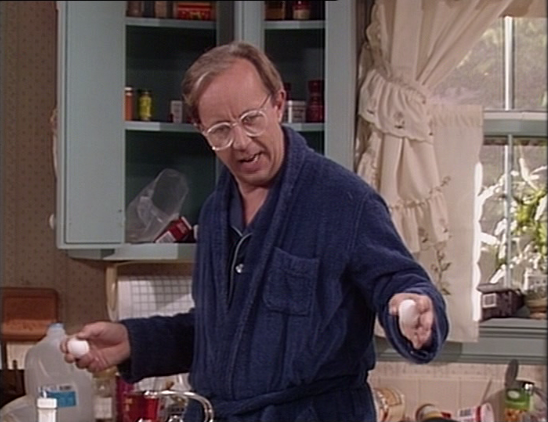

Anyway everyone bitches again and then Willie waves some eggs around.

While Mr. Ochmonek is out of the house, Mrs. Ochmonek and Jake come over with more of his stuff, including a moose head so that Willie can humorously sit next to it and make funny faces in a moment, even though there’s a completely vacant sofa like one foot away if it’s such a big fucking deal to him.

Mrs. Ochmonek says their separation is final, because the script told her to. She says she saw her husband coming out of Mrs. Bird’s house first thing this morning! Through a pair of binoculars, of course. He was there to pick up milk for the Tanners, which we know and she does not, and which the Tanners don’t seem all that intent on telling her about.

Nice family, huh?

There’s the germ of a very good idea here, but I know why the show didn’t go that route; it’d require taking the limited amount of characterization this show has actually done into account.

Remember, Mrs. Ochmonek was first and foremost introduced as the neighborhood busybody. That might have fallen away over the past two years, but that’s okay. Just look at how The Simpsons introduced characters for one very specific purpose, and then found much (much) more interesting things to do with them later. Original roles can evolve. In fact, they absolutely should.

The problem with Mrs. Ochmonek is that nothing’s really been introduced to take the place of her faltering nosiness. That, too, is okay, if a little unfortunate. But “Breaking Up is Hard to Do” is in a perfect position to get the character back to her roots (er…root) and, for the first time, spin an actual plotline from it.

We’ve already got the foundation for it right here: because she’s nosy, she spotted her husband coming out of another woman’s house. That’s the kind of thing that might spill out in the writer’s room, and it would be the perfect reason to go back and revise the previous pages of the script, giving this episode some strong, character-specific resonance.

Specifically, here’s what I’m getting at: have the initial fight between the Ochmoneks come from something similar. Maybe Mr. Ochmonek comes home late, and his wife is convinced he’s having an affair. She starts spying on him and sees things that can be easily enough misinterpreted as evidence of an affair…a problem that doesn’t exist, but which she’s creating in her own mind because she’s the kind of person who butts into other people’s business. For instance, you could see Mr. Ochmonek walking into a jewelry store with another woman. Mrs. Ochmonek kicks him out of the house without giving him a chance to explain, and maybe without even telling him what she saw.

Of course, it turns out to have been a coworker or someone, and he was trying to pick out a nice gift for his wife and wanted a woman’s opinion before he made the purchase.

Groundbreaking? Fuck no. But ALF isn’t interested in breaking ground, and I’m okay with that. When I look at ways to fix the show, yes, it’s easy to say nuke it from orbit. But assuming we’re not doing that, and we’re going to adhere to tried and true conventions of the format, there’s still so much room for improvement. ALF can be better without ever having to be original; all it needs to do is step back, take a look at the universe it’s built (deliberately or not), and create stories from that, rather than spit out whatever first comes to mind and hope for the best.

Mrs. Ochmonek should be a busybody who created this conflict by virtue of being a busybody. Instead we still don’t know what they fought about* or what a reconciliation would entail. That means it’s not only impossible to get invested, but we don’t know why we should want to be invested. Without knowing the stakes, we don’t care. If we don’t care, we probably aren’t laughing.

Once again, the importance of second drafts, ladies and gentleman. It’s not a luxury upgrade…it’s the bare minimum you need to keep an audience watching.

The Willie sits next to the moose and prays to God.

Yes, really.

He asks God why He puts “such ordinary people in such extraordinary situations.”

…which is a pretty strange thing to ask in reference to his neighbors having a spat, as opposed to…oh, I dunno, a giant space roach rampaging through the house, the president sending him to Guantanamo, his uncle falling down dead in the back yard, an alien singing about how nice it would feel to fuck his teenage daughter, his boss showing up at the house for an impromptu Halloween limbo party, film crews stumbling upon the actual flying saucer in his garage, or Anne Ramsey threatening sexual violence against him.

Willie’s got one hell of a strange sense of what’s worth bothering God with, I must say.

Then ALF burps and Willie says, “lol nevermind!!!!!!”

Yes. Really.

The fuck is this show. Who laughs at this?

Later on, ALF is in the garage, calling people in the town to see if they’ll let Mr. Ochmonek stay with them. None of them, I guess, ask who the fuck is calling them. He’s not impersonating Willie’s voice or anything…he’s just a stranger asking a stranger if a stranger can live with them for a while. I don’t care. I hate my life.

He actually manages to get Mrs. Bird on the line, and it’s Beverly Archer…the same actress that played her last time. Oddly, though, this is it. We hear only a snippet of her conversation with ALF, and then she is neither seen nor heard again. Why did they bother paying her to reprise the character for this? The way she gets name-dropped throughout the episode you almost expect her to play a part in whatever the big resolution at the end turns out to be, but…no. First draft. Always the first draft.

Then Mrs. Ochmonek comes over to bitch Willie out for telling the neighborhood her business, and the joke I guess is that she lists off the last names of all the neighbors and they rhyme or something.

Then Willie goes over to bitch ALF out for telling the neighborhood her business, and the joke I guess is that he repeats the list of neighbors and they rhyme or something.

Willie is actually really fired up, so once again I have to wonder why this situation — of all the fucking situations ALF has dragged him into — has him so furious. Since when is he more passionate about Ochmoneks’ love life than he is about the safety and financial security of his own family? Perhaps being in a position in which he must help another human being is King Social Work’s kryptonite.

Maybe if it was Jake getting upset at ALF, this would make sense. In fact…why isn’t it Jake? He has a significant personal investment in the state of their marriage, and he knows ALF exists, putting him in a position to confront him about his meddling. It’s a far more natural way for this to play out, and, besides, Jake is already in this episode. Why not give him a fucking purpose?

Seriously guys…these are all thoughts I had the first time watching the episode. Could it really be that hard for writers who got paid to do this to come up with something better than they did?

Anyway, Willie leaves and there’s an admittedly cute little moment when ALF reaches for the phone, and then quickly withdraws his hand as Willie turns around. Then he orders flowers for Mrs. Ochmonek because he gives even less of a shit about what Willie thinks than we do.

Mr. Ochmonek sees the flowers later, and he comes into the garage to yell at Willie for sending flowers to his wife. It’s not a great scene, but there are some funny moments, including an unexpected one from Max Wright**: Mr. Ochmonek says he’s upset because no man would send a $79.95 flower arrangement to another man’s wife unless he knew he was causing trouble.

Willie replies, “There must be some seventy-nine ninety-five??”

And, yeah, I’ll give him that one. That was a great delivery, and genuinely funny.

Then there’s a humorless exposition dump, because it was either that or go back and add better jokes to the earlier scenes.

ALF sent the flowers so it’d look like they came from Mr. Ochmonek, but Mr. Ochmonek knows he didn’t send them, so he called the florist and they told him it was billed to Willie’s credit card.

No joke, I wonder how often florists get calls like that. I’m genuinely curious. Anyone out there ever work in a florist? Maybe a jewelry store? Is it a fairly common thing for them to get calls from men asking who the scumbag was that just sent gifts to their significant other?

Mr. Ochmonek then threatens Willie to stay away from his wife, otherwise “I’m moving out of your house.” It’s a good line delivery from Jack LaMotta, lacking all self-awareness and believably upset. It’s good comic acting.

This was probably the best scene in the episode, which isn’t saying much. Or maybe I’m just biased because it opens with Willie cramming ALF into a cardboard box.

ALF and Jake break into the Ochmoneks’ bedroom, because hey, why not. They’re looking for a clue about how to get them back together, which I guess makes sense because they live in a sitcom and the episode is almost ending. Whatever’s going to resolve the plot has to be lying around somewhere.

Yeah, it’s all riding at a fast clip toward whatever disappointing conclusion the writers manage to crap out.

A good joke (ALF seeing a display of little hula girls and being impressed by how much class the Ochmoneks have) even veers immediately back into standard ALF horseshit (ALF lifts a grass skirt to jack off to some sculpted pussy). It’s fucking gross even before you remember that he’s doing this in front of a kid.

Then Mrs. Ochmonek comes home after having had a fight with Mrs. Bird — off camera, apparently — then Mr. Ochmonek comes home after ALF called him saying a terrorist was in the house, then I kill myself.

ALF, hiding under the bed, tosses a scrap of paper out to Jake, who picks it up in his only relevant action in the entire episode. It turns out to be a poem that Mr. Ochmonek wrote to Mrs. Ochmonek way back in a year the writers didn’t bother to figure out.

Actually, it’s the lyrics to Chicago’s “Just You ‘N’ Me,” which goes for some pretty lazy laughs of recognition when it’s read out loud, but Mr. Ochmonek’s “I meant every word I stole” does actually manage to redeem it.

Anyway, now they’re back together. Being as they had no real reason to be apart, I suppose it’s fitting that this just kind of happens and nobody has to work through any of those pesky emotions the writers have heard so much about from their colleagues on better shows.

In the short scene before the credits, ALF comes out from under the bed. Hilarious!

He says to Jake, “You’re more than a life saver. You’re a milk dud.”

And when that’s just about the cleverest thing in the entire episode — and the punchline to which 25 minutes of this shit have built — you know you’ve wasted a lot of time that you could have spent eating a bag of nails.

So…how do you solve a problem like the Ochmoneks? This episode doesn’t know, but it certainly tries a lot of things and abandons them along the way. The odd-couple pairing of Willie and Trevor could have worked, if we got more than a scene or two of it. The home-wrecking Mrs. Bird seemed to be positioned as a willing antagonist to the couple’s happiness…but then nothing came of that either. We were also in a prime position to explore the dynamic of this relationship…learn a little more about them, perhaps, or at least spend some time learning about who they become when they’re no longer together.

Instead of exploring that dynamic, we get an invented and disposable conflict. Jake is there for the sake of being there, but we never get a sense of why this matters to him. (Apart from the fact that he could be shipped off again if they split up.)

The Ochmoneks are the closest thing this show has to reliably good characters. That’s the good news. The bad news is that the show still hasn’t figured out what to do with them. I’d like to give them credit for trying, but all “Breaking Up is Hard to Do” proves is that when you try to weave something good into the ALF universe, that goodness suffers far more than the universe is improved.

If you missed this episode, don’t worry. Next week is a clip show, so we’ll see some of it again. Yep, after a whopping three episodes, it’s time for this season to start resting on its laurels.

I’ll see you then. :(

—–

* At one point we do hear that Mrs. Ochmonek sees her husband as a slob, and that’s the closest we get to an explanation. But that clearly isn’t a new development in their relationship, and she’s never had a problem with it before, so I don’t buy it. Not on its own.

** I’ll take those wherever I can get them.