Let’s talk about a masterpiece.

Mega Man 2 is, simply, a game that cannot possibly be spoken of too highly. It’s one of the most important games of the NES era, and one of the absolute best games overall. It’s not perfect — whatever unhelpful definition of “perfect” we decide to endorse today — but it does much of what it sets out to do perfectly. It’s a finely honed, impressive, addictive, tight, magical experiment that pays dividends far beyond what anybody — gamers, critics, the developers themselves — ever imagined.

That’s certainly great. What makes it even better, though, is how little Mega Man 2 actually had to do differently from its predecessor. Almost everything here was already present in Mega Man. All Mega Man 2 had to do to become one of the best-regarded games of all time was tighten the bolts. It singlehandedly demonstrates the importance of polish.

In fact, Mega Man 2 feels a bit like a rewrite. Forgive me for going all literary on you, but that’s sort of what I do. Writers out there understand — even if they’d prefer not to — the value of rewriting. And rewriting. And rewriting. And rewriting. No matter how good we think our first drafts are, they’re not as good as they should be. I’ve spoken before about how I’ll often go through around 100 revisions of a post here before it ever goes live. And when it does I inevitably find something I wish I had written differently.

That’s not to say that my first drafts don’t have merit. They do, if only as foundations for the superior text that I’ll build on top of them. In fact, I’d argue that everyone’s first drafts have merit in that way; it’s up to us to make good on that merit, to respect it enough to cut what isn’t working, to give ourselves over to the material so that we’ll act in its best interests, to not cling to our mistakes and missteps. It’s a difficult process, and it’s not one writers often let anyone else be privy to. Your favorite novel — whatever your favorite novel is — sort of sucked at one point. It really did. It’s just that you never saw it until it sucked a lot less.

Mega Man is the first draft. Full of great ideas, heavy with potential, and just excited to get out into the world and show an audience what it has to offer. Mega Man 2 is the rewrite. Bigger, yet leaner. Just as daring, but smarter. Every bit as charming, but smoother in its delivery.

Mega Man 2 is a great game. It’s the one I’ve played through the most, it’s the one I know best, and it’s the one I love the deepest.

It’s also, unfortunately, the game that set a precedent that would ultimately cripple the series…but we’ll come to that later.

The leap forward is evident from the opening moments of Mega Man 2. When you slipped the first game into your NES and turned the system on, you’d see a static and silent title screen. Press start and you’re tossed right to the stage select. I think it’s fair to say that there’s nothing inherently wrong with that, but I think it’s just as fair to say that Mega Man 2‘s opening beats the pants off of it.

We get a little bit of exposition that explains not only the concept of this game, but of the previous one as well. After all, if you didn’t have the instruction manual — which you certainly didn’t if you rented it — you never would have known the story of Mega Man without finishing it and watching the end credits. Which you certainly didn’t, because you were 10 years old and terrible at video games.

Mega Man 2, funnily enough, knows that its audience likely wouldn’t be familiar with its predecessor’s plot even if they played it, and it lays out the story of both games up front. The year is 200X. Dr. Light built Mega Man. Dr. Wily flipped some robots’ switches to EVIL. Mega Man kicked their butts, and now Wily has built some robots of his own to strike back. The arms race is officially in full swing.

It doesn’t really seem like the most impressive video game story, but it starts to feel impressive as the camera pans upward…and upward…and upward…windows on a building gliding downward as the music picks up pace…as we sonically and visually climb…as we soar to the top of this impossibly tall building to find something…something important…something meaningful…

And it’s Mega Man. Himself. Alone.

He’s just staring into the distance. Perhaps down at the city. The night wind ruffles his hair. He’s waiting for you, but he’s in no rush. He’s content to wait forever.

When you press start, Mega Man responds to you. To you! And you’ve barely done anything yet! He puts his helmet on and teleports away, ready to fight. He’s at your command.

Before you’ve even started the game you’ve engaged with it, you’ve interacted with it, and you see exactly how far the series has already come. That silent, static title screen from the first game sure feels like a lifetime ago. Mega Man 2 represents a cosmic leap (teleport?) forward, even though it doesn’t have access to any tools that the first game wasn’t already using.

It’s just, already, using them better.

The fact that Mega Man 2 released only one year after its predecessor was both a remarkable achievement and a foreshadowing of the eventual series fatigue that would quickly set in, and which Mega Man has never been able to shake. Granted, Mega Man 2 did release later in North America, giving the first game a little more breathing room, but every single year between 1987 and 1998 would see a release of a new, main-series Mega Man game in either the East or the West. In fact, 1992 saw the release of both Mega Man 4 and Mega Man 5 in the US, and this is to say nothing of the myriad spinoffs and side series bearing the Mega Man name.

Even as kids we got sick of the games being pumped out so frequently, and ridiculed the series for it. To be frank, that’s probably also why we stopped playing. I can only speak for myself, but I didn’t feel like I’d be missing much if the company making the games treated them like they were disposable.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. The point is that a gap of just one year separated Mega Man from its sequel, which was an incredible accomplishment that all too quickly became a worrisome pattern.

We’ll deal with those games later, though. (Aside from Mega Man & Bass, which I may just treat as an aside in the Mega Man 8 review. I’m open to feedback on that.)

The concept of a sequel serving as an incremental improvement (as opposed to a more substantial reinvention) was obviously nothing new to video games, but the oft-mentioned triumvirate of “strange second entries” — Super Mario Bros. 2, Zelda 2, and Castlevania 2 — stand as a point of comparison that shows just how confident the Mega Man series was in its own formula.

Those other games followed up their huge initial success with brave experimentation, and so Mario did away with his patented stomp, Link began to accumulate experience points, and Simon Belmont taught a crash course in Engrish. The Blue Bomber, however, did the same thing he did last time around. The other three franchises moved their bets around the table, but Mega Man let his ride.

It was the smart bet. While those other three franchises view their second installments as black sheep today — interesting curios that are fascinating mainly for how quickly their ideas were discarded — Mega Man 2 is one of the NES’s crown jewels…and, for my money, the best of the series.

So, what’s different?

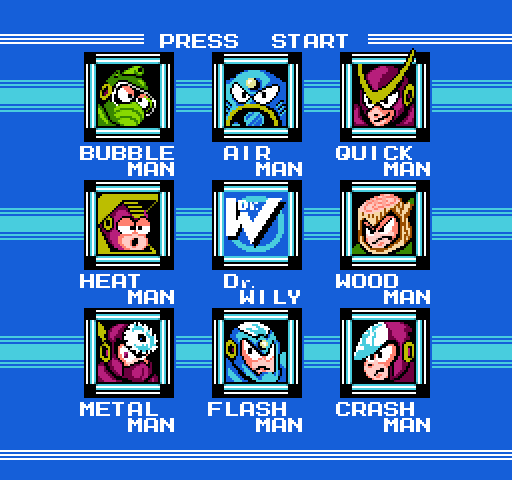

Well, there’s the obvious stuff. Eight Robot Masters instead of six. Twelve weapons and items to play around with rather than eight. A map screen for the Dr. Wily stages. A password system, for honest and dishonest use as we saw fit. A capsule room for the boss refights, rather than haphazardly (and unevenly) scattering them around the last few stages. E-tanks for an invaluable health refill.

Fine.

We know all that. It’s worth remembering just how much of what we now know as the Mega Man formula this game establishes, sure, but those are just things. Things we can list. Things we can point at. Tangible things we can arrange into a nice list of bullets and never think about again.

What really matters is the difference in how the game feels, and that comes down to the changes made in less obvious areas: the controls and the design.

When I refer to the controls, I refer to pretty much exactly what you’d expect. Mega Man himself controls more tightly. The physics are tweaked so that both climbing and falling feel more natural, and he no longer suffers from that slight skid that plagued him in the first game. (I have a friend who swears that Mega Man still skids in Mega Man 2, and it wasn’t corrected until Mega Man 3. My friend is mentally ill.)

But I’m also referring to something you might not expect: the controls are actually more varied than they were in the first game. You can play Mega Man 2 just as simply as you played its predecessor, but you can also tap into a layer of additional complexity, which is where much of the fun comes from.

In Mega Man, all of the weapons worked the same way: you’d press B. That’s it. For your default Mega Buster that’s certainly fine, but you’d press B to toss a Rolling Cutter, B to throw a Hyper Bomb, B to trigger the Fire Storm…and, really, it doesn’t take long to see that all you’re doing is attacking with differently shaped projectiles.

That’s not to say that Mega Man‘s weapons are bad, but it is to say that they’re simple. They lack nuance. If you and I use the Ice Slasher we’re both using it in the same way, because there is only one way to use it.

Mega Man 2 retains the simple “press B to shoot” mantra of the first game, but it doesn’t stop there. Press the D-pad along with the B button to launch a Metal Blade in any of eight directions. Hold the B button to rapid fire Quick Boomerang after Quick Boomerang. Press the D-pad after pressing the B button to throw the Leaf Shield. Hold B to charge the Atomic Fire.

The weapons in Mega Man 2 encourage and reward experimentation, whereas the weapons in Mega Man did not. The weapons in Mega Man 2 expect you not just to play with them, but to learn how to best use them.

Of course, now we’re veering into design, and rightly so, because that’s where we can talk about the utilities.

In Mega Man, the Magnet Beam — the game’s single utility — was, I suspect, born as a graceless answer to the game’s own design flaws.

I have no way of confirming this for sure, but the Magnet Beam’s ability to place a number of straight, flat platforms directly ahead of Mega Man seems like a way of addressing a playtesting problem with the flying Footholder enemies in Ice Man’s stage. As I discussed last time, their AI is genuinely random, which means that they can — and often do — drift around without concern for ever actually getting you over the pits. They are your single mode of transportation across Ice Man’s chasms, but they have no particular interest in assisting you. This means that you could pretty easily end up in a situation in which they’ll never bring you across.

So, how do we address that?

We either improve their AI, which would be an unquestionable drain on the development staff’s resources and might still not provide a viable alternative…or we create another solution. And since Mega Man was already shaping up to be a game of alternate solutions, with special weapons that could be swapped out at will to best address any given situation, wouldn’t that be more in keeping with the game’s ethos anyway?

And, so, the Magnet Beam was possibly born. Mega Man can now create his own platforms, and he won’t have to rely on the game’s in-built bumbling, glitchy ones. Even the utility’s placement in the game feels like an afterthought. It needs to be somewhere, so it was put somewhere. The problem is the fact that the mandatory Magnet Beam is in Elec Man’s stage, yet it requires the Super Arm* to retrieve, which interferes with the any-order-you-please core of the Mega Man experience.

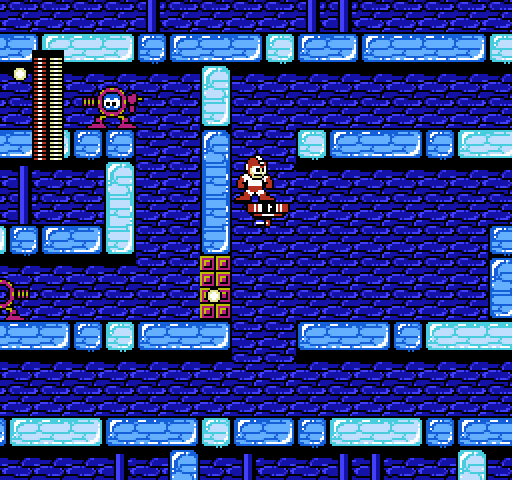

Already we’re able to see ways in which Mega Man 2 improves upon the first game. In Air Man’s stage we have our equivalents of the Footholders: the Thunder Chariots. These move in a fixed pattern, meaning you’ll never have to worry about whether or not they’ll let you make it over a chasm, and have an enemy on top that you’ll need to defeat before hopping on. This both retains the challenge of the originals and makes it far more fair.

Then, obviously, we have the utilities themselves. Item-1 is a small platform that slowly rises and can be placed three at a time. Item-2 is a rocket sled that rushes quickly forward in a straight line. Item-3 is a piece of hard candy that climbs up and down walls or some ridiculous thing there’s no point in using.

…except that there is, potentially, a point in using it. If it’s all you’ve got, you’ll experiment with it to fit your needs.

The big difference with the utilities in Mega Man 2 is that they don’t address fundamental design problems the way the Magnet Beam did. They’re given to you along with special weapons at the end of three main stages, and the game lets you treat them as new toys. Any one of them can help you make it to new places, but not all of them will. Or, at least, not easily.

If you need to reach a platform a little higher than you can jump, Item-1 is the obvious choice. But if you only have Item-3, you need to learn its quirks and figure out how to get up there using that instead. Or you need to place Item-2 and use it as a platform, jumping off quickly before it rockets you away from your goal. If you need to cross a long gap, Item-2 is the obvious choice…but you could also place a series of Item-1s, replacing each one as it disappears, hoping you have time to make it far enough horizontally before they lift you too far vertically.

Mega Man 2 is very much a game that rewards players for having the right tool for the job, but it doesn’t punish them significantly for having the wrong one; it just makes them work a little harder to get the result they want. Mega Man offered alternate solutions; Mega Man 2 offers alternate solutions to those alternate solutions.

All of which is to say that the game is perfectly designed, and there’s no room for complaint at any point.

ha ha you forgot what site you’re reading

Longtime reader Samuel Caribou had this to say in the comments to my Mega Man article:

The people who were making this game had so many crazy ideas that they were so excited to show off. Even if the Yellow Devil fight is admittedly cheap, you can tell the game designers were absolutely over the moon about it. This was 1987, and they were making a massive boss that would make enemies like Bowser look like a shrimp. […] These were ideas that needed quite a bit more time to cook, but the absolute tenacity that the team at Capcom had is something I’m awed by.

I think he’s right, and that’s also why it’s so hard to stay mad at the first two Mega Man games in spite of their faults. (Don’t worry. We’ll get and stay mad soon enough.) These games were bursting with so many new, unique, and exciting ideas that it’s difficult to begrudge them for having less-than-stellar execution.

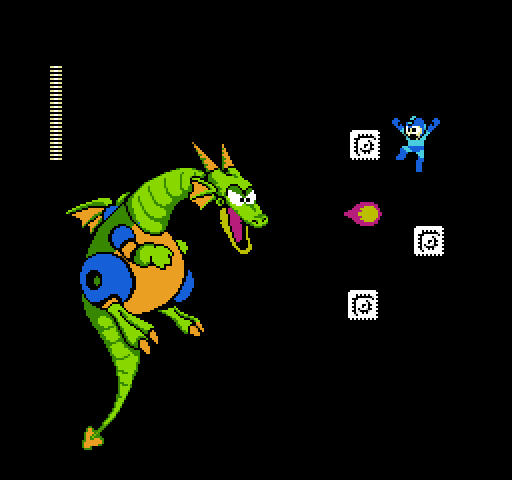

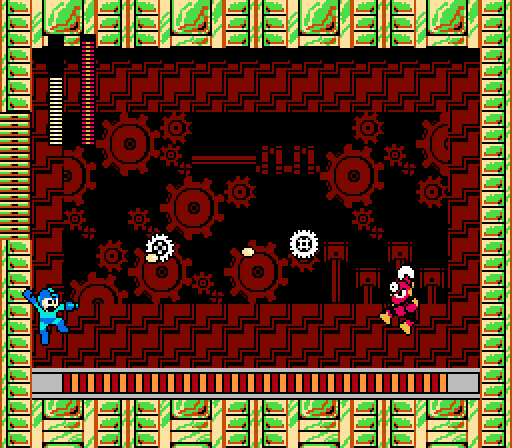

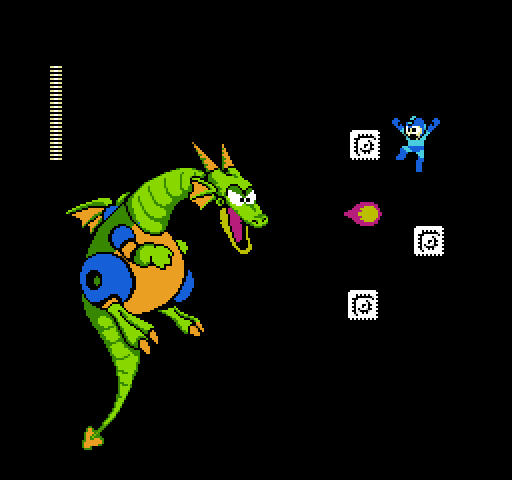

The Yellow Devil fight was indeed cheap — and overlong, and annoying — but wasn’t it also thrilling? Ditto Mega Man 2‘s equivalent showstopper, the Mecha Dragon. Funnily enough, both bosses occupy the same space: the end of the first Wily stage.

The Yellow Devil fight was frustrating mainly because it’s almost impossible to understand what’s happening until it’s already killed you. You enter a pitch black room, and you stand there. Alone. Some worrying, anxious music plays. And then, all of a sudden, little chunks of…something zip inexplicably across the screen, with you standing in the way. Yes, they come in a pattern. Yes, the pattern is easy to learn. But no, there’s not really time to learn it before the chunks of Yellow Devil — which you see gradually assembling itself audience right — kill you. The collision damage is significant, and there’s no way to heal. You’re dead before you can even open fire.

But, again…thrilling. Looking back it’s easy to nitpick that fight, but it’s also still pretty easy to see why we overlooked its flaws and focused instead on its spectacle.

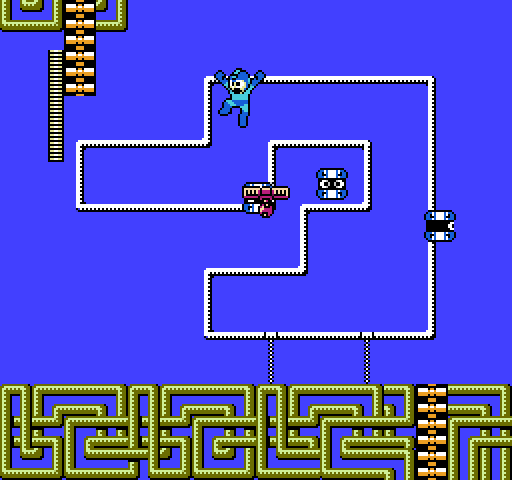

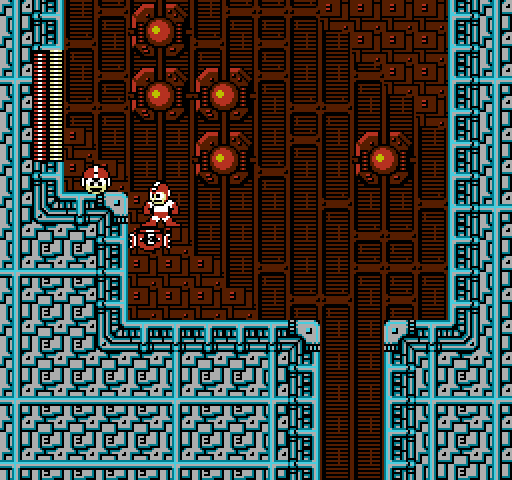

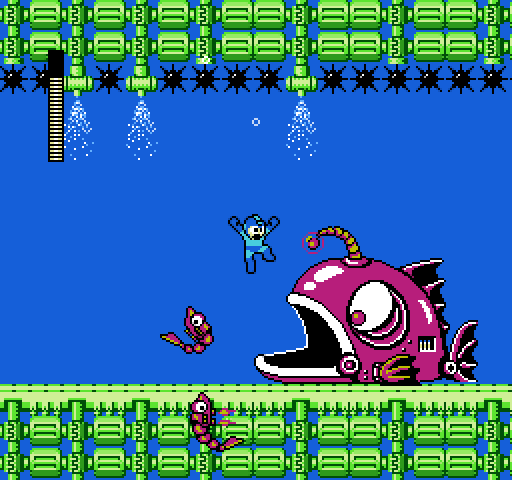

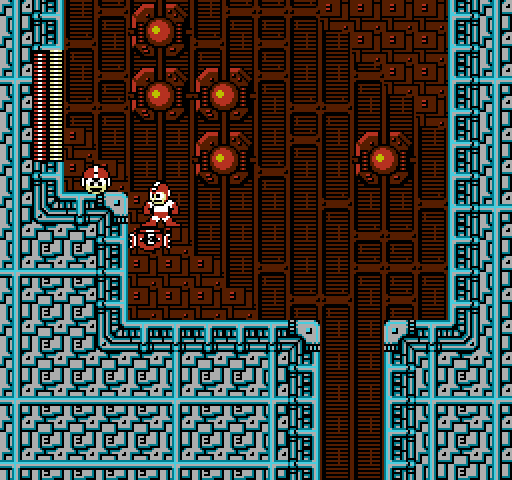

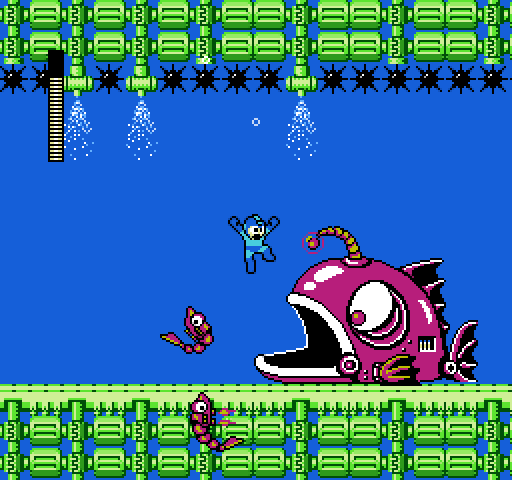

The Mecha Dragon pulls a similar trick. You enter a dark area. There’s nothing ahead of you aside from some narrow blocks. You start hopping along them. The screen scrolls automatically for the first time in either game. And then, just as you’re learning the rhythm of leaps and pauses, an enormous robotic dragon comes crashing through the platforms to chase you the rest of the way.

We all remember the spectacle…

…but, damn, this sequence is flawed. And cheap.

For starters, it’s a bit too much at once. The disorientation of the autoscroll is one kind of obstacle, but combined with the too-narrow platforms it becomes borderline unfair. The sequence doesn’t allow time to think; if you’re wondering what to do next, you’ve already fallen to your death.

Then there’s the Mecha Dragon himself, who can kill you by crashing up through the platform you’re standing on. Which means you’re supposed to stay as far to the right as possible. Which is both counter-intuitive (you already have limited reaction time…why would you stay to the right and reduce it further?) and impossible to guess (there’s no indication that anything will come crashing up from the bottom, let alone where it will happen).

Oh, and touching the Mecha Dragon is a one-hit death at this point…but at the end of the sequence, he’ll just do a chunk of contact damage. That means the developers deliberately made it less fair during the chase.

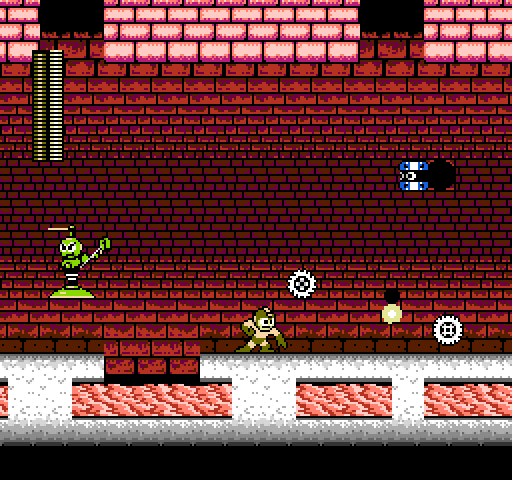

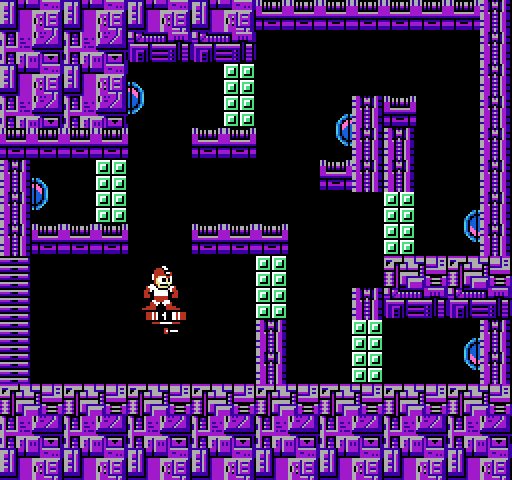

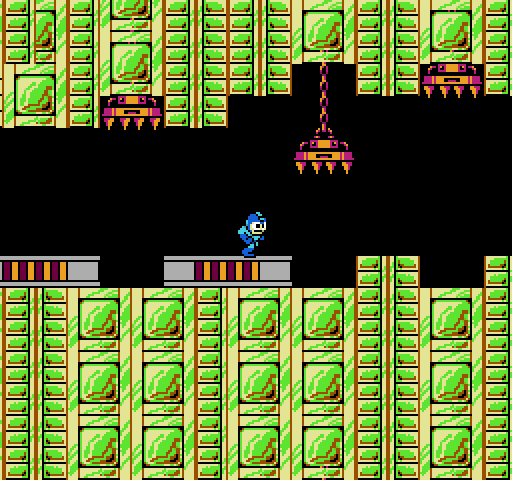

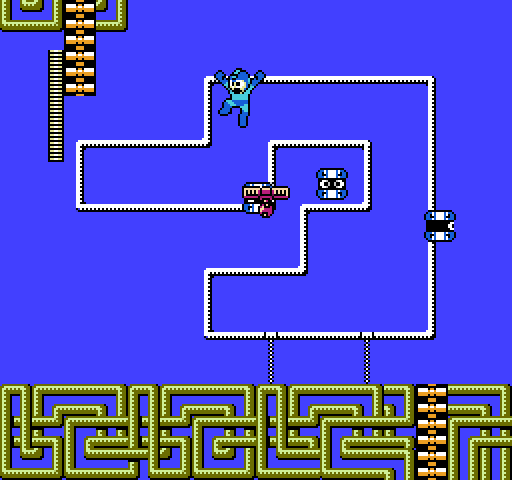

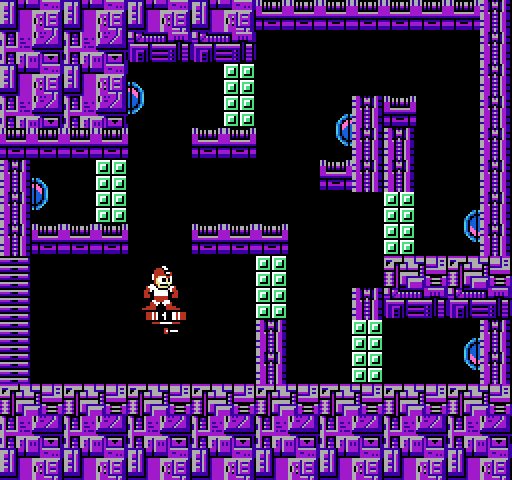

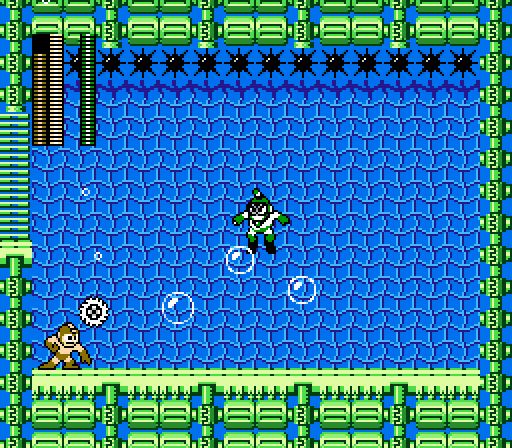

The other major lapse in design comes with the Boobeam Trap in Dr. Wily’s fourth stage. Here you have a set of turrets that can only be destroyed with the Crash Bomber…many of which are hidden behind walls that can only be destroyed with the Crash Bomber. The Crash Bomber itself is a very inefficient weapon, and you don’t actually have enough weapon energy, even with a full charge, to defeat the turrets and take out more than a small number of walls. And that’s assuming that you enter the boss fight with a full Crash Bomber charge, which you likely will not unless you know you’ll need it ahead of time.

As such it’s a bit of a puzzle boss, which can be frustrating in itself, but it’s made worse by the fact that if you die — which you unquestionably will your first several times fighting it — you are dropped into a corridor with enemies from whom it is very difficult to farm weapon energy. On top of that, you’ll need to use your utilities during the fight in order to climb up and around the barriers, meaning that even if you do manage your weapon energy well enough, you’d better hope that you managed your utilities just as well.

What’s more, the Boobeam’s projectiles are incredibly fast and well-aimed…not to mention the fact that they come from all directions until you take out some of the turrets, making it just about impossible to avoid taking significant damage.

In theory, I like the Boobeam Trap. It’s a wise decision to incorporate utilities into a boss fight after providing so many opportunities to play with them in less-dangerous situations. And yet I can’t imagine a worse implementation than what we got here. To quote Jeff Goldblum in Jurassic Park, “They were so excited about the things they could do that they ended up making stuff that kind of sucked a little bit.”

But, if you’ll notice, these design issues all come from the Dr. Wily stages, which I’ve already said are nearly always a bit of a letdown. The main stages in Mega Man 2 are incredibly fun, and even the worst of them is better designed than any of the stages in this game’s predecessor. They’re more varied, more clever, more full of secrets, and backed by what has got to be one of the all-time greatest gaming soundtracks.

Sure, Heat Man’s tune is bit weak by comparison (perfectly fitting of its environment, though, I concede), but when it came time to choose a best track for this article, I was conflicted. At least half of the main stages have songs that deserve the title, and another three are…well, pretty darned close.

There’s the soaring majesty of Air Man’s theme. The prancing tease of Quick Man’s laser drop. The slippery disco of Flash Man’s maze. The meditative haze of Bubble Man’s song. The music here is just incredible, and I don’t think it’s possible to sing its praises enough.

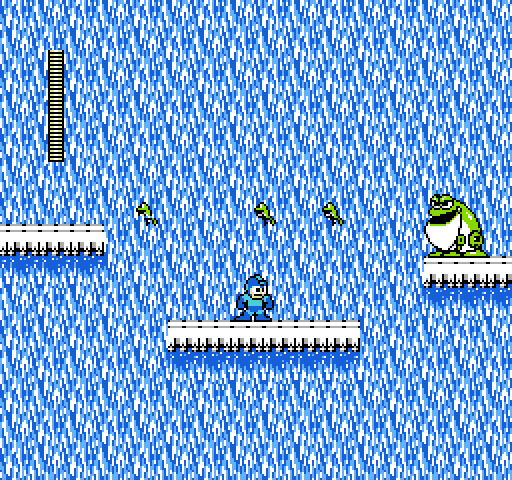

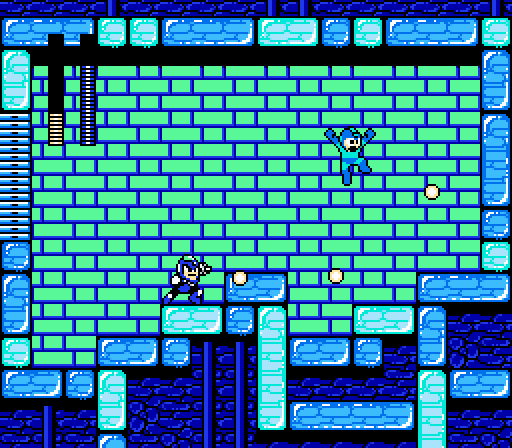

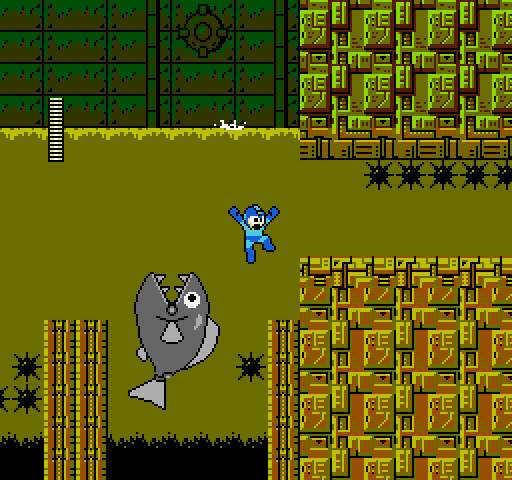

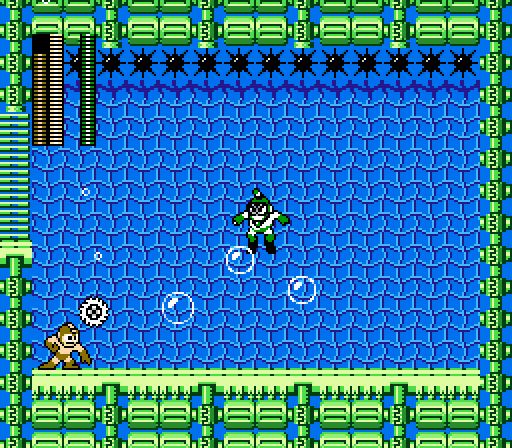

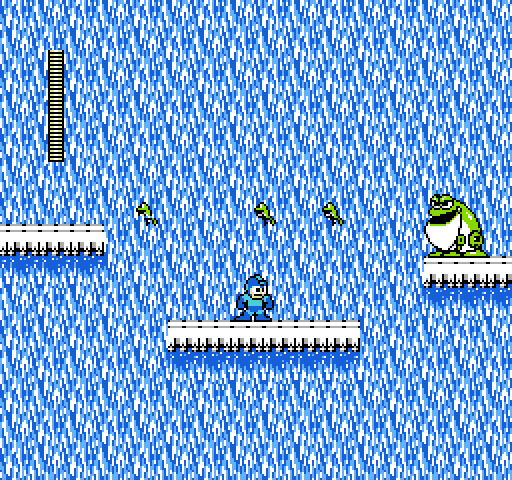

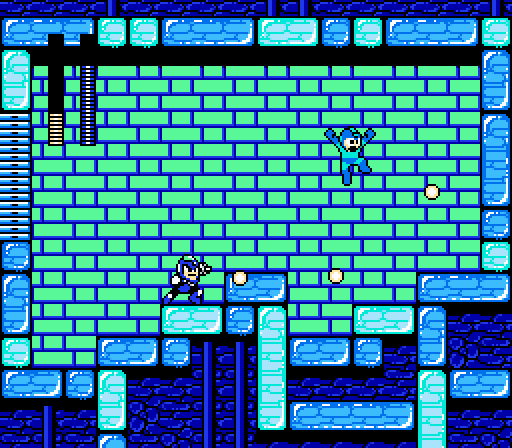

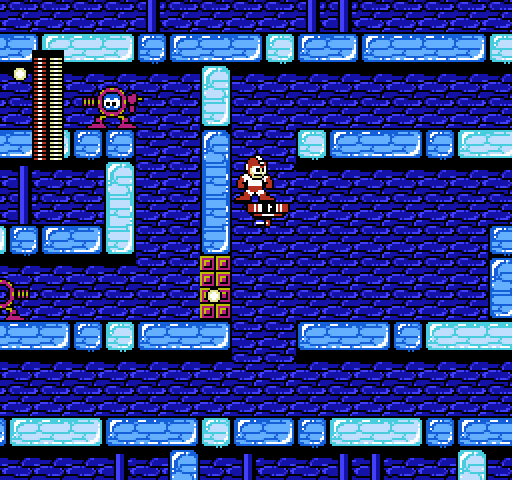

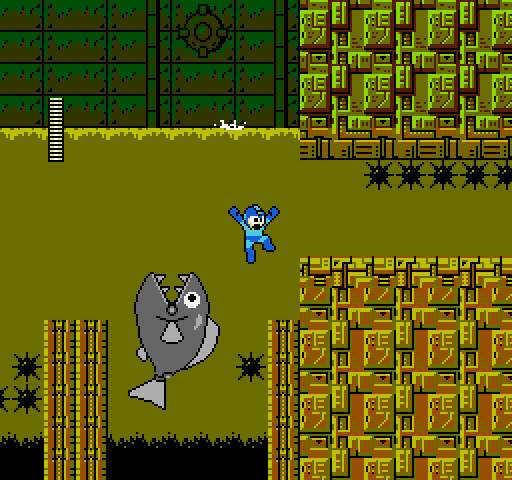

The music, though, would mean little if it wasn’t underscoring some truly great stage design. Bubble Man’s stage is probably the highlight, if only for the brilliant progression of its background and gimmicks. Mega Man starts outside of what seems like a dam, learning to manage his jumping and firing across narrow platforms with enemies of different sizes. Advancing a little further brings him to platforms that drop…a more urgent indication that careful attention to jumping will be necessary. Then there’s a long plunge down into a body of water, where more enemies of varying sizes invite him to manage jumping and firing again…only this time with water physics. The shrimp enemies move gracefully through the level, at angles that benefit them more than they benefit you. They’re a reminder that you’re on somebody else’s turf now…

Here is where you learn the ropes of Mega Man’s buoyancy, which at first is just a question of lining up his shots, but which will soon become a matter of life and death as the ceiling becomes lined with spikes at varying heights. After fighting your way through more enemies and navigating tight, deadly passages, you pretty much have a handle on the water physics. In fact, instead of the graceful shrimp enemies you end up fighting the clumsy, mindless frogs from the beginning of the level, only now there are no pits and you’ve learned to manage the water. You feel like you’re more capable. More experienced. And you’re right. You’ve made progress.

Then, just as you start feeling comfortable, you’re outside again. It’s platforms with the waterfall in the background, and little robot crabs dropping out of the sky to knock you to your death. I hope all that stuff underwater didn’t cause you to forget the “careful jumping” lesson from the beginning of the stage! Finally you drop into a second, smaller reservoir, where Bubble Man waits…and you’re forced to remember the lessons of buoyancy again.

It’s a great level and a decent fight, especially if you’re attempting to clear it with no damage. And I admit that it holds some sentimental value as well: Bubble Man was the first Robot Master I ever defeated. Maybe that’s just because his stage was fun enough that I kept coming back to it. Whatever the reason, he gave me my first special weapon to play with…and inspired me to keep going. Almost 30 years later, I still am.

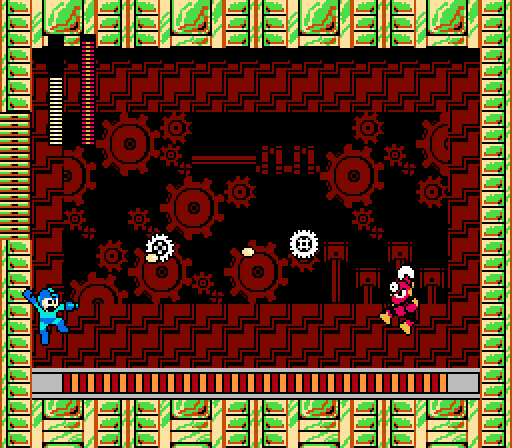

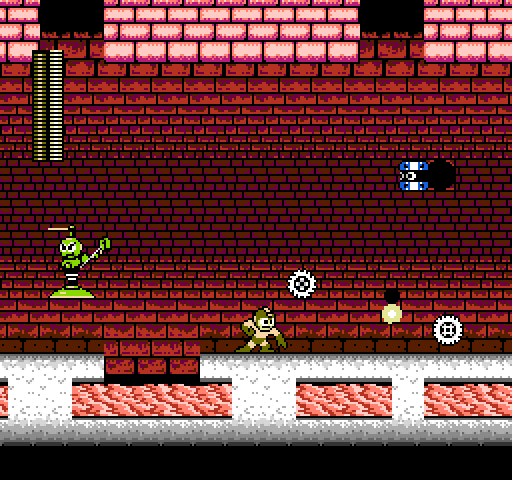

I won’t go through each of the levels, because then I’d never get to talk about any of the other games, but there’s a tangible love behind each one that I can’t help but feel every time I play. Crash Man’s incredible tower climb into the night sky. Flash Man’s pulsing, driving, twisting level that always feels more interesting and impressive than it really is. Metal Man’s accurately dangerous robot factory, swarming with traps and OSHA violations. Everything is just so…good.

They’re not all fantastic, though, I admit.

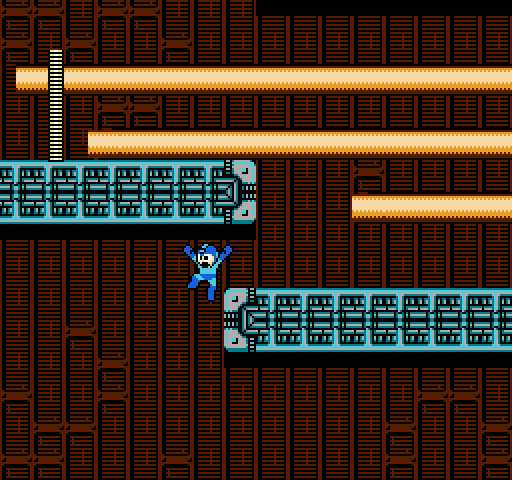

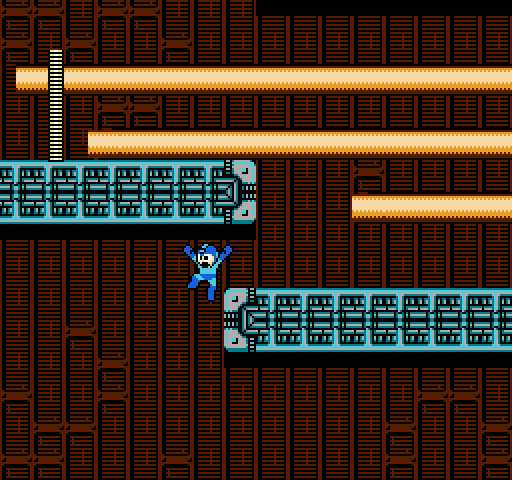

Heat Man’s stage is…okay. It’s not bad, but the disappearing block section is frustrating at worst and tedious at best. The block pattern is actually not difficult to learn, but it goes on far too long and, as with the Yellow Devil fight from the first game, there’s no way of knowing what the pattern is — fair or not — before it kills you a good number of times. It’s an irritating stretch in an otherwise incredible game, and as much as I love Mega Man 2 I’m content to pull out Item-2 and skip it every time.

Then there are the Quick Man lasers, which…okay, they’re kind of bullshit. One-hit kills that you can’t quite predict. Of course, the Mega Man series freezes the action during screen transitions, which does help players to orient themselves during this section, and does give a brief insight into where the lasers might come from…but this is another stretch that simply can’t be completed the first time through. Fair stage design implies that a skilled player should reasonably be able to figure out how to progress without having to make any life-ending mistakes. Here, though, it’s just a mad dash through instant death traps, and the fact that I can do it easily today in no way excuses the laziness of those traps.

So, no, Mega Man 2 isn’t perfectly designed. But…I might say that it’s a perfect experience. The Mecha Dragon still thrills me more than it concerns me. The Boobeam Trap is simple enough, now that I know to expect it. The Heat Man blocks are easy to avoid. The Quick Man lasers, if anything, remind me of how tirelessly I worked as a kid to figure them out…and how I never gave up until I did.

The fact that I did give up on many other games when I didn’t give up here speaks to the incredibly high quality of Mega Man 2. I had no patience for crap like that as a child…but I kept going. Because, on some level, I knew that Mega Man 2 was worth it.

I haven’t second-guessed that thought since.

Ultimately, Mega Man 2 is the game we all thought we were playing when we played the first Mega Man. It still has its flaws, but what game doesn’t? It’s a refined version of the addictive template we experienced in the original, one so well constructed that it illuminates flaws that we never consciously realized Mega Man had.

Many years after I finished college, I got a job for the state government. I had a little Mega Man action figure on my desk. My boss used to love those games, too, and we’d talk about them. He was older than me, and yet his memories of the series were just as vivid and fond as mine were. We bonded over that.

One day he pointed to the action figure and said, “You know, that toy makes him look like a little kid.”

But Mega Man always looked like a little kid.

It’s just that we saw something so much bigger when we looked at the screen.

Best Robot Master: Crash Man

Best Stage: Bubble Man

Best Weapon: Metal Blade

Best Theme: Air Man

Overall Ranking: 2 > 1

(All screenshots courtesy of the excellent Mega Man Network.)

—–

* You could also play through Elec Man’s stage twice, as the Thunder Beam can remove the obstacles that fence off the Magnet Beam, but that’s clearly not the intended method of retrieving it and is in no way any better a solution to the problem.