Prior to this review, I had seen Big Top Pee-wee exactly once in my life. After this review, I can assure you I’ll never watch it again.

As we discussed last week, I loved Pee-wee. I loved Pee-wee’s Big Adventure. I loved Pee-wee’s Playhouse. And yet when Big Top Pee-wee came out, I had no desire to see it at all.

You’d think, maybe, that I had tired of the character or his antics, at least to some degree. But I know for a fact I hadn’t. Big Top Pee-wee came out in 1988, and Pee-wee’s Playhouse was still on the air until 1991. I watched that show until the very end, and was surprised and disappointed when it didn’t come back for another season, so I’m sure I didn’t suffer from Pee-wee fatigue.

And I know that Pee-wee’s Big Adventure was still in our regular movie rotation. Many of my friends had copies, and we’d still pop it in and watch it. I remember this because one of my friends — only one — also had a copy of Big Top Pee-wee. And we never wanted to watch that.

I don’t remember much about the advertising for the film, but I have to assume something turned me off immediately. Sure, I was seven years old and couldn’t get to a theater on my own, but my parents took us to see Who Framed Roger Rabbit? and Bambi, which were both in theaters at about the same time as this film, so I have to conclude that I simply didn’t want to watch it.

I should have wanted to see Big Top Pee-wee, but I didn’t. And when finally I did see it with my friend…man, we hated it.

Hated it.

Exactly as much as we loved Pee-wee’s Big Adventure and Pee-wee’s Playhouse, we hated Big Top Pee-wee.

As I grew up and shared memories with friends in high school and college, I learned that they all had the same reaction. Pee-wee was great, but Big Top Pee-wee was unquestionably awful.

But here’s the thing: nobody brought up any specific complaints.

We could all bond over our favorite bits of Pee-wee’s Big Adventure, but nobody ever mentioned any particular reason that Big Top Pee-wee was bad. No quotes, no scenes, no sequences. And it wasn’t just my friends; Big Top Pee-wee was a film that nobody talked about. Ever. It was never mentioned as anyone’s favorite film growing up and never even mentioned as disappointing, outside of conversations that were already about Pee-wee.

It existed. We all saw it. But, like war, it was an experience we’d prefer not to discuss.

The closest thing to actual criticism I remember anyone having is that Big Top Pee-wee was a love story. And, yeah, sure. I’d buy that that was a problem. I was a stupid kid. I didn’t want to see Pee-wee fall in love; I wanted to see him talking to puppets and riding an awesome bike over a Godzilla set. If Big Top Pee-wee was about…ew…relationships, yeah, I could see myself tuning out. In fact, the one distinct memory of the film I had was Pee-wee strutting around in the dark, playing a love song on an accordion while a woman threw glass at him. The story checked out.

And, in a way, that was pretty good news. While I wouldn’t have had the patience for some sappy, boring love story at age seven, I sure as hell have the patience now. Revisiting a film that disappointed you as a kid only to find some real merit and heart in it as an adult is one of the great joys of growing up. About maturing. About understanding so much more of the world that you’re able to see beauty where you saw nothing at all before.

So I sat down to review Big Top Pee-wee. Not as a kid with a thirst for excitement and silliness and bright colors and corny jokes…but as a man. As a critic. As a grownup who understands that the most rewarding art takes its time and makes you work for it.

And fuck almighty does Big Top Pee-wee suck an egg.

Watching this movie through patient, receptive, adult eyes offers no insight whatsoever into what Paul Reubens — or director Randal Kleiser, of Grease and The Blue Lagoon fame — was trying to accomplish. It’s a trainwreck from beginning to end…the kind of film that starts off pretty bad and gets significantly worse almost every minute that follows. In fact, I’m writing the first draft of this review only a few minutes after watching it, and I wouldn’t be able to identify a plot arc to save my life.

Honestly, the most difficult part is figuring out where to begin. With Pee-wee’s Big Adventure, I had to actively look for things to bring up as problems. (And here’s another one I forgot: the studio chase goes on way too long. But it’s pretty cool and Twisted Sister sings “Burn in Hell” so…yeah, still can’t think of much.) Big Top Pee-wee is the opposite; I’m afraid that once I start discussing its flaws, I’ll keep going until I’m dead.

Alright, I think I can say something nice, and I can do it by describing the basic conceit of the film. So, that’s good, and probably a fair place to start.

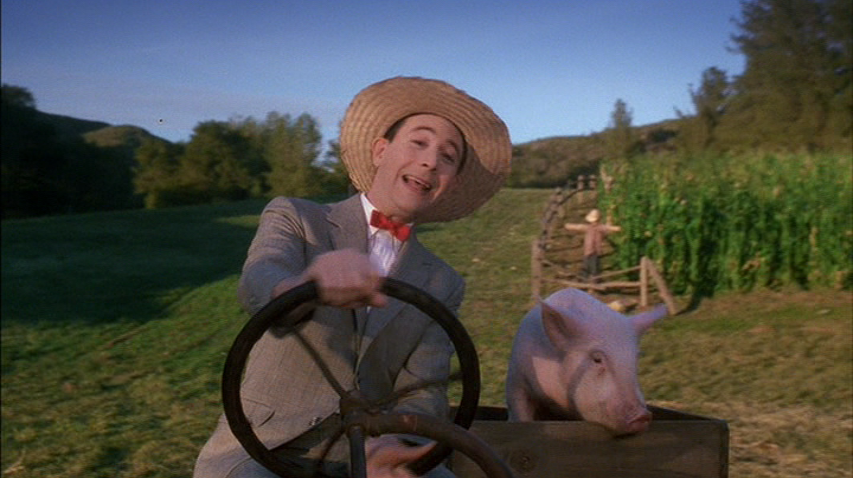

Big Top Pee-wee introduces us to a version of the character that runs his own farm. To go into any more depth about that would be to immediately start rambling about how terrible this movie is, so I’ll just skip ahead to the fact that a storm comes through, depositing a circus on Pee-wee’s land. To go into any more depth about that would also be to immediately start rambling about how terrible this movie is.

So, here’s what I like: each of the three Pee-wee films (and Pee-wee’s Playhouse) features a different incarnation of the character. They live in different places, they associate with different people, and while they’re largely the same in terms of how they think and behave, there are at least small differences in what they specifically want and what they specifically find important.

And I like that. I think it was a good impulse to not make this a sequel to Pee-wee’s Big Adventure so much as a successor. We don’t have to worry about where Pee-wee and Dottie end up as a couple, or what scheme Francis is cooking up to steal the bike again, or whether or not Amazing Larry will share his comments with the rest of us.

It’s wise to set a precedent for each Pee-wee production being a self-contained little world. They each get to succeed or fail on their own merits. We don’t go into them with any particular expectations, and we’ll have less of a temptation to measure them against each other. It also allows Reubens and company to take the character in unexpected directions without any necessary connective tissue. If Pee-wee is a private eye in one movie and an astronaut in the next, we never need to learn how he went from one to the other, because he didn’t. Pee-wee was always a private eye, and Pee-wee was always an astronaut.

So far, so good.

Where Farmer Pee-wee falls down is that son of a bitch does this movie stink.

Farmer Pee-wee just isn’t as…interesting. The Pee-wee we know from big adventures and playhouses was less a character than he was a presence. He didn’t grow or learn or change…he was just Pee-wee. He just existed. That was thrilling and liberating in its own way, but it also meant he could show us anything. Part of the fun of watching him was wondering where he’d end up next, and what he’d do when he got there.

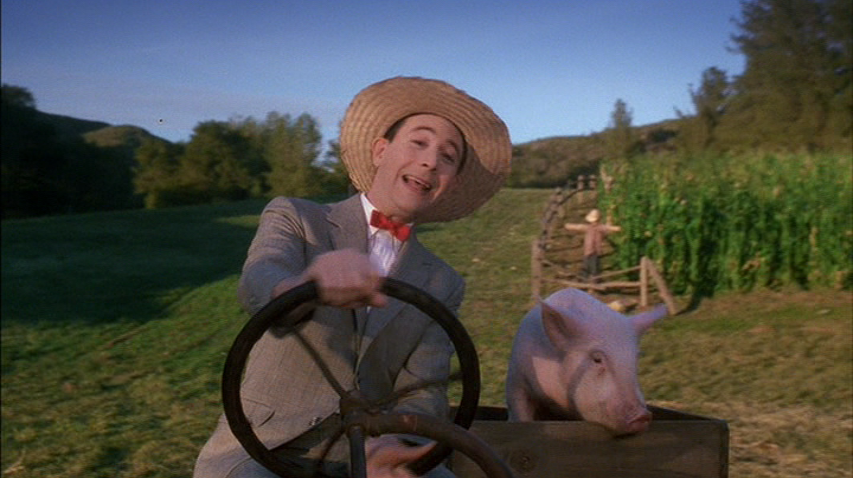

Farmer Pee-wee, by contrast, wakes up and does chores. Sure, he’s still in his grey suit and red bowtie, but now he’s tilling land and tending animals and shopping for groceries. There’s a reason he didn’t do any of that stuff in Pee-wee’s Big Adventure or Pee-wee’s Playhouse: it isn’t any fun.

I get the feeling that Big Top Pee-wee is, in fact, supposed to be fun. Which is disappointing in its own way, because if the entire concept were that Pee-wee lived some boring life before the storm came through (see Dorothy Gale for the obvious template) and the circus taught him how to have fun, that would be a neat idea.

Instead, though, Pee-wee does seem to be already having fun. It’s just that the audience, to a man, is not.

Even the music — again by Danny Elfman — can’t seem to find any joy in the proceedings. In Pee-wee’s Big Adventure it was positively bursting with creativity, incorporating and bleeding into sound effects and cues that came directly from the action on screen. That film’s soundtrack is catchy, memorable, and instantly made Elfman’s career as a composer. Here…well, there’s still music. But I sure don’t remember any of it.

I can’t blame Elfman for that, really. The previous film’s opening had Pee-wee’s incredible (and incredibly convoluted) breakfast machine as its centerpiece, giving Elfman a fun, silly, mechanical device upon which to hang all of his musical hooks. Wheels turned, robots swiveled, slices of toast were launched…Elfman had plenty to work with, and I wouldn’t be shocked if he started his original score duties with that scene and wrote the rest of the compositions from there.

Big Top Pee-wee, in stark contrast, opens with Pee-wee slowly harvesting vegetables by hand. And that’s just not as…inspiring. Especially to someone like Elfman, who thrives on outsized, bombastic quirk.

It’s a bit odd seeing Pee-wee so overwhelmingly happy in this film, at least somewhat due to the fact that there’s no clear reason for him to be. In the previous film, his house was packed with toys and games and candy and gadgets and magic tricks and everything else a little kid could want. Pee-wee, a little kid in an adult’s body, was understandably enamored with this life.

Here, he’s just in a house. A pretty boring house. On some pretty boring land. There’s animals everywhere, I guess, and that’s kind of cool…but Pee-wee waking up excited to get down on sustainable agriculture is not the same as Pee-wee waking up excited to crash a firetruck into Mr. Potato Head. It’s just not…interesting.

I said in my review of Pee-wee’s Big Adventure that the film created a universe in which Pee-wee’s outlandish eccentricities fit. Big Top Pee-wee does the opposite, creating a universe in which Pee-wee’s eccentricities no longer fit the character itself. They’re just…there.

Pee-wee looks and sounds like Pee-wee, and often acts like Pee-wee, but he doesn’t seem to have any reason for being here. In fact, you could swap him out for any other vaguely dimwitted character of your choice, and the film would play out almost exactly as it already does. That’s something you absolutely, positively could not say about Pee-wee’s Big Adventure.

Also, Big Top Pee-wee has a talking pig and fucking fuck the fuck on.

I…

Like, I honestly don’t even understand it. Why does this movie have a talking pig? I have genuinely no clue what they were going for.

Maybe that’s the quirk the movie thought it needed, but it feels entirely misplaced and unsuitably cartoony. Pee-wee’s Big Adventure was a thousand times more cartoony than Big Top Pee-wee is, and a talking pig would have been out of place even there.

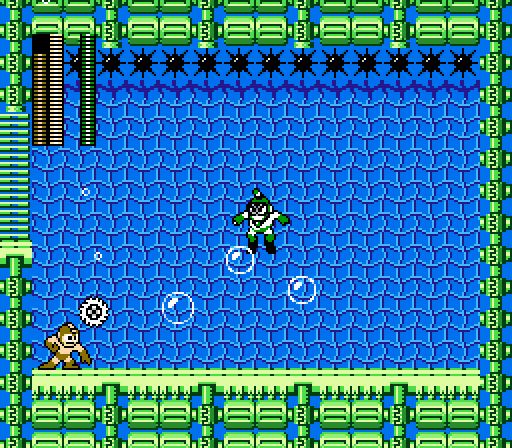

In fact, we can compare and contrast a bit. In Pee-wee’s Big Adventure, there’s a scene in which our hero calls Dottie from a payphone. She holds the phone out for Pee-wee’s dog, Speck, who grumbles and barks at his owner through the receiver.

Speck doesn’t hold the phone himself, Speck doesn’t talk, Speck doesn’t climb through the phone and lick Pee-wee’s face or any kind of crap like that. The dog just acts like a dog. Pee-wee jokes around with Speck, pretending they’re having an actual conversation and eventually asking him to put Dottie back on the line, but the joke is that they aren’t really having a conversation. That sort of goes out the window the moment the animal talks back, wouldn’t you say?

And as long as we’re making direct comparisons, let’s compare Pee-wee’s flames.

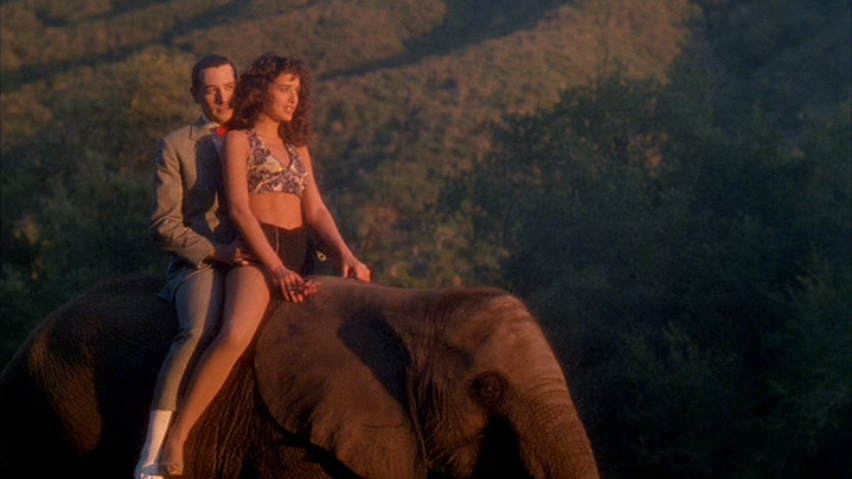

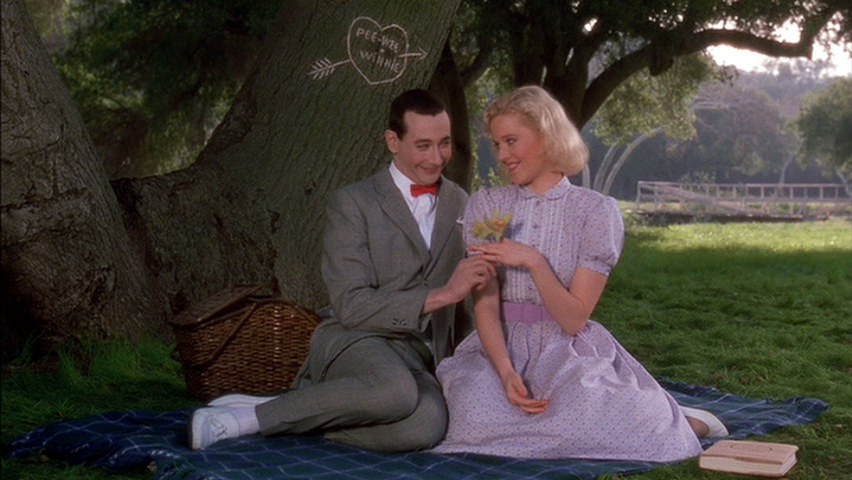

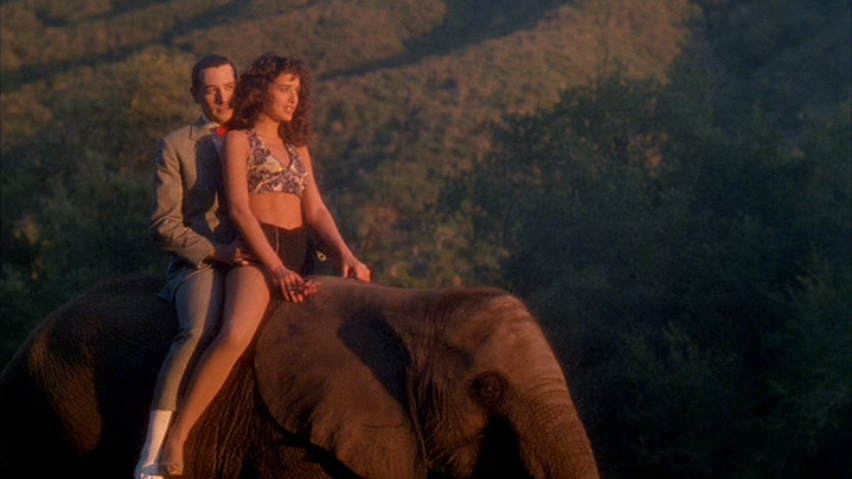

In a word, Gina in this film is no Dottie. In a few hundred more words, I’ll explain fully.

See, as with the talking pig, Big Top Pee-wee misses what was funny about the first film. It corrects for a problem it never had, cheapening the experience as a result. Here, it’s the spark of romance. And as with talking animals, the first film was funnier for not having one.

Dottie adored Pee-wee. That was clear. It was also the joke. Pee-wee…well, he’s Pee-wee. He dresses and acts like an idiot. He’s often selfish and always self-absorbed. He sees very little beyond himself or his most immediate need. He’s completely and totally disinterested in romance, to the point that his response to Dottie’s overtures is less a rebuff than it is a vacuum. Dottie gonna dote, and that’s funny because Pee-wee is both oblivious to and undeserving of the doting.

There’s also a classic moment in that movie in which a large man chases Pee-wee around huge, artificial dinosaurs, intending to bust his head open…because he thinks Pee-wee’s been smooching with his girl, Simone. The joke, of course, is that there was nothing romantic between Pee-wee and Simone. Simone may have had a little bit of a crush on him, but it’s only made funny by the fact that Pee-wee appears to be utterly sexless. Not only did nothing happen; nothing could have happened. He’s Pee-wee. He might as well be a Ken doll.

Big Top Pee-wee loses all of the comedy of these non-romances and introduces a profound new layer of discomfort by letting Pee-wee…erm…reciprocate? I don’t know; I’m trying to think of a better way to put it than “letting Pee-wee fuck.” But rest assured, this is the movie nobody asked for in which Pee-wee fucks.

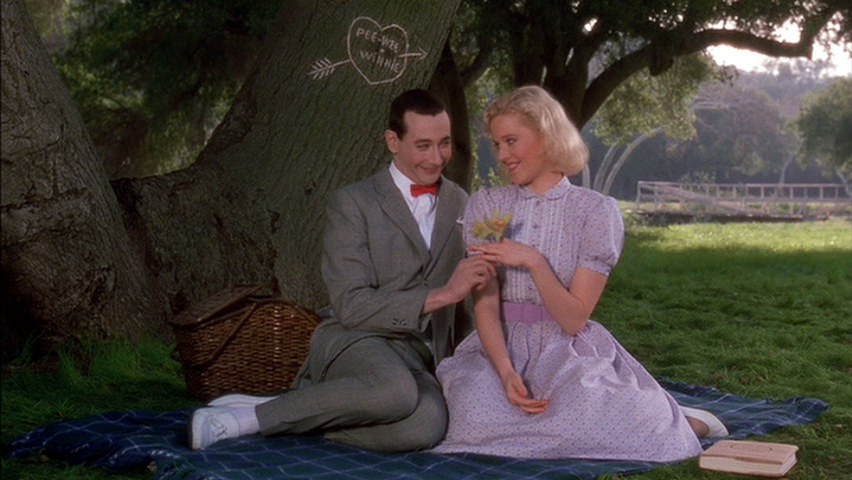

And it’s not just the fucking. It’s the fact that Pee-wee is constantly horny. Long before he and Gina get Pee-wee Hammerin’ he’s drooling all over her, flirting heavily with her, making out with her by a waterfall. You know. All the stuff Pee-wee should never, under any circumstances, do. And earlier in the film he literally can’t control his urges, hopping on and dry humping his fiancee Winnie. It happens multiple times, and it’s really pretty gross.

That’s right; fiancee. It’s certainly bad enough that this incarnation of Pee-wee actively seeks to insert his penis into things, but it’s also problematic in his treatment of Winnie. Yes, he shrugged off Dottie in the first film, but the joke was pretty clearly two-fold: he was clueless, and she should have known better. Here he strings his fiancee along until he tires of her (because she won’t let him fuck her in front of a group of children…I shit you not), and then makes out with sexy trapeze artist Gina behind her back.

He doesn’t leave Winnie or put the breaks on with Gina; he just pursues both of them for no reason with very little consequence. (Winnie leaves him but they remain super awesome totally great friends, as you do after you’re exposed for actively cheating on your significant other.) He’s just kind of…awful.

Pee-wee is always kind of a dick. I know that. That’s actually part of what makes him funny, and oddly endearing. But here he’s just a sex-obsessed idiot, which is neither funny nor endearing…especially in a children’s film. And after Gina (rightly) dumps his ass for two-timing, he wins her back not with a grand gesture, not by saving the circus, not by doing anything in the least bit selfless, but by bothering her relentlessly, night and day, against her clearly communicated wishes, until she spreads her legs just to shut him up.

And they lived happily ever after.

Fuck this movie.

Well, I say movie. It’s certainly long enough to be one, but it doesn’t behave like one. For starters, there’s no plot. Sure, Pee-wee’s Big Adventure had a decidedly inconsequential plot, but there’s a big difference between “decidedly inconsequential” and “completely lacking of.”

Here, I’ll illustrate. We can easily identify the primary plot points of Pee-wee’s Big Adventure, and see that it’s a clear and natural sequence of events: Pee-wee loves his bike, Pee-wee’s bike is stolen, Pee-wee seeks his bike, Pee-wee finds his bike.

Now, Big Top Pee-wee: Pee-wee works on a farm, a storm puts a circus in Pee-wee’s yard, Pee-wee woos an acrobat, some old people shrink because they eat magic cocktail wieners.

Bet you think I made up that last one, huh?

I didn’t, and that’s the way the movie ends.

Pee-wee’s Big Adventure was relentlessly silly, but every sequence followed from the previous and led into the next. Part of the reason it’s such a watchable film is that it flows so naturally from beginning to end that it’s easy to get swept away by it, even at its most ridiculous.

Big Top Pee-wee just does something, then another thing, then something else, then it ends. It feels careless, as though it were assembled from outtakes from a whole slew of different Pee-wee movies, all of which were terrible.

Narrative arc, of course, is one thing, but character arc can and often does make up the difference. For instance, The Royal Tenenbaums lacks a strong narrative arc, but it makes up for it (and then some) with important, incredible, artfully explored, deeply intertwined character arcs. Try to tell the story of The Royal Tenenbaums and you won’t have much to say, but try to explain what the characters go through and you can spend hours without scratching the surface.

Not that I’m suggesting Big Top Pee-wee needs to have anything in common with that film or its approach, but it’s a useful example to keep in mind as we look at what this movie does, or fails to do. It has no discernible plot arc, and it doesn’t rely on inventive setpieces and wacky comedy like its predecessor…so does it go the character route instead?

It does not. Pee-wee makes no progress as a human being, aside from the rite of passage of losing his presumed virginity. Not that that actually registers as much of an event. It just…happens, and we move on. Gina likes him again, though, charmed forever by the Pee-wee Hardon. Pee-wee at the end of the film does do a brief tightrope walk, which fulfills his goal of participating in the circus, but it’s a goal that was mentioned exactly once earlier and which he could only have had for a few days at most.

So what about Gina? Does she grow or change or learn anything? Of course not. She’s there to be made out with and plowed. She fulfills both purposes and accomplishes (and wants) nothing else.

Winnie — an underused but reasonably game Penelope Ann Miller — likes Pee-wee and then leaves him to marry four different men at once. I don’t know what that is, but it’s certainly not a character arc. Maybe it’s a joke about how she wouldn’t give it up to him but is perfectly happy getting gang-banged. It’s unclear. I’m glad for that much.

Also she joins the circus because why the fuck not.

Then there’s ringmaster Mace Montana, played by an only partially drunk Kris Kristofferson. He gets a lot of screentime, but to no real end. He sets up his circus on Pee-wee’s land and kind of…walks around a lot, I guess? I don’t know.

He’s in a lot of scenes but I’d have a hard time telling you much of anything he said. At the end of the movie he puts on his circus for everyone, which isn’t much of a character arc as that’s, y’know, his job.

The minor characters are similarly wasted. For the most part they’re just standard circus freaks (a bearded lady, a two-inch-tall woman, a human cannonball, a…hermaphrodite…), but we get a few that seem to be more important and go just as nowhere.

Michu Meszaros — yes, the little fellow in the ALF suit — plays Andy, who has a good amount of lines but doesn’t seem to have been given a personality. It’s a little disheartening to see him in this film, because Reubens seems to think it’s enough that he’s small. Meszaros doesn’t get any jokes, say anything important, or do anything of significance. He just keeps getting trotted out like a freak, which is odd, because the film also suggests that circus folk deserve to be treated like actual people. (Spoiler: in the end, they still aren’t. The old people who hated them just shrink because they eat magic cocktail wieners.)

The dog-faced boy is played by Benicio del Toro in his first major role, and I assure you it’s no longer on his resume. He’s another character who gets a lot of lines but has no more significance than anyone else. At one point he makes dog noises, which I’m reasonably certain is meant to qualify as a joke.

Then there’s a mermaid and the acrobats who fuck Pee-wee’s ex and a clown named Snowball who Kristofferson calls Showball in what I’m certain was a blooper nobody was paying enough attention to reshoot.

I don’t care about any of these people. Ever. For any reason. None of them mean anything to me, whereas Pee-wee’s Big Adventure gave me a huge smile just by showing me Jan Hooks. Or by having Mickey the criminal praise Pee-wee’s film from a prison bus. Or by surrounding Pee-wee with Satan’s Helpers and letting him get out of his pickle in a uniquely Pee-wee way.

What I mean to say is that everything in that movie was a delight. It went from great scene to great scene, with so much to enjoy at literally every point. In Big Top Pee-wee I didn’t care once. It’s more than a step backward; it’s a fundamental disinterest in providing an experience of any kind. It’s just…there.

While researching a few basic facts about this film, I saw that, at some point while promoting it, Reubens said that the cast spent a year and a half going through circus training. Imagine if they spent a year and a half writing jokes instead.

In the end, I don’t care how well Pee-wee or his fuckbuddy perform stunts. If I want to see circus acts, I’ll go to the circus. There’s also the sad fact that while it might be impressive that Paul Reubens can briefly walk a tightrope after 18 months of practice, it’s not anywhere near as satisfying or interesting to watch as someone who has spent his life honing more impressive feats. Even as circus spectacle, it fails.

No, I didn’t want to see this circus crap. I wanted to see Pee-wee. I wanted to see comedy. I wanted to see inventiveness and creativity and giddy, silly fun.

But instead I got…nothing.

Nothing at all.

Just something that ate another hour and a half of my life, and didn’t seem to have any idea what it wanted to do with it.

And then Big Top Pee-wee just…stops, no wiser than I am about whatever it was trying to say, or accomplish, or make me feel.

I think that says something. Maybe it says everything.

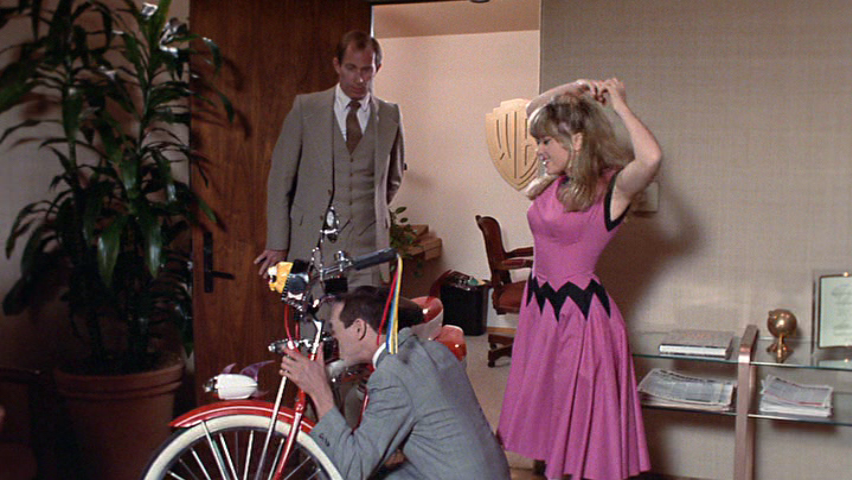

In a nice bit of series continuity, we’re introduced to each film’s incarnation of Pee-wee in a dream. In Pee-wee’s Big Adventure, he dreams of winning the Tour de France on his beloved bicycle, tying neatly into the film we’re about to see. In Pee-wee’s Big Holiday, he dreams of saying goodbye to an alien buddy, setting up the main themes of the film: Pee-wee’s desire for close friendship and his reluctance to leave home. Great.

Big Top Pee-wee also opens with a dream, in which Pee-wee croons “The Girl on the Flying Trapeze” to an audience of fawning women. It’s very un-Pee-wee, and also doesn’t tie into the film at all. Sure, he eventually does fall for Gina, who suits the description, but his fantasy is about being a famous singer…not a guy who shuffles along a tightrope for a few minutes at the end of a shitty movie.

Like the film itself, it’s just…there.

There’s also a running joke about Pee-wee’s pig getting repeatedly violated by a sexually aggressive hippopotamus.

I could have left that out of the review pretty easily so…you’re welcome.

My dislike of the film is obviously not unique. Pee-wee’s Big Adventure made around six times its budget at the box office, turning it into a surprise hit. Big Top Pee-wee, by contrast, lost five million dollars…which was almost the entire budget of Pee-wee’s Big Adventure, to put it in perspective.

It’s possible that we might have gotten another Pee-wee movie had Paul Reubens not run into legal trouble in 1991, but I think it’s fair to say that after Big Top Pee-wee, nobody was clamoring for another film. Possibly not even Reubens, who can’t have been ignorant of its commercial failure and toxic reputation.

But time passes. Nearly 30 years in this case. And we eventually did get a third Pee-wee film.

At this point, the record was split. One film timeless and thoroughly enjoyable, the other a joyless flop.

Which way would Pee-wee’s Big Holiday tip the scale?

We’ll find out next week.