Who is Willie Tanner?

That’s not the kind of question I should be asking 34 episodes into this show. Willie is one of the central characters, after all. But if I were to make a list of all of his traits — actual traits — it would be ridiculously short. I’ve talked before about Kate feeling like the only real character on this show, so using her as a point of comparison would be pretty unfair. But by this point, I feel as though I know Mr. Ochmonek, and even Lynn better than I know Willie.

In “Somewhere Over the Rerun,” I spoke a bit about why ALF, as a show, could never work as the fantasy setting for some other show’s episode the way Gilligan’s Island did there. Ultimately, it’s the fact that the characterization on ALF held steady at a perfect nil.

If the audience doesn’t know anything about the characters, there’s no reason to miss them when they’re gone. The nostalgia simply doesn’t come. You’d end up talking about ALF like you were trying to describe a dream. You could probably rattle off a few things about the central detail — the alien, in this case — but anything else you’d say would have to be pretty hazy. “There was this guy…with glasses. And sometimes he liked ALF, but sometimes he yelled…he wore a suit…I think he had kids…”

Which is why I wanted to take some extra time — an extra week, in fact — to write about “Night Train.” This isn’t ALF‘s first attempt to answer the question of who Willie is, but it’s certainly the better one. In “Jump,” we learned a hell of a lot more about Kate than we did about him. And while nothing that we learned about either of them has been mentioned even once since, I still believe that Kate was once the type of person who attended the Running of the Bulls just for the thrill of it. I do not believe at all that Willie’s the kind of guy to give two shits about jumping out of an airplane because he wrote it on a piece of paper decades ago.

“Jump” rang hollow. It wanted to tell us who Willie was, but it failed to make any kind of coherent — let alone lasting — statement about him. At that point* it was probably already too late to tell us who this character was. By this point it is positively a lost cause.

And yet, “Night Train” takes its job seriously. It tries to get us to believe that Willie Tanner is a character, and then it tries to convince us that he’s a certain type of character.

That’s ambitious, pure and simple. And I respect that. So let’s put “Jump” behind us. Hell, let’s put the previous 33 episodes behind us. Let’s engage “Night Train” on its own merits. That’s the least we can do. It’s going to try to do something interesting, so let’s be fair and see what it comes up with.

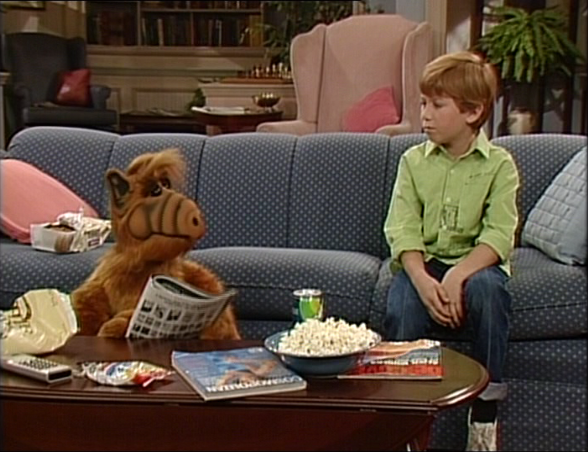

Anyway, the opening scene is ALF yakking about how brave he is. Kate reminds him that he hid under the couch shitting himself when they all watched Aliens, and he replies that he was only scared because “I thought I owed one of those guys money.”

Like the Space Invaders joke that ended “Border Song,” this is good. It’s a bit of a throwaway, but when it comes to throwaways, this is the right way to do it: tie it into something specific to the character. In an alternate universe where ALF is actually the freeloading Uncle Alfred, this joke wouldn’t play. I like that. It shows that the writers were giving at least some thought to who would actually be delivering these lines.

It’s a small moment, and I don’t intend to over-sell it. But the fact that it opens an episode that intends to explore character? Well…that’s pretty reassuring.

Then ALF convinces Brian to jump off the roof, because of how great this show is for families. Oddly, the writers don’t actually let him do it, in spite of the fact that it would free them from having to come up with some pointless line for the kid to say every week.

Anyway, Willie’s not in the opening scene, but we see him come home in the next. He enters his bedroom to find ALF in his bed. Kate’s absence is alluded to, but not explained. It’s a little odd, and it’s the kind of thing that better writing could hide.

See, Kate can’t be present for this conversation. The story wouldn’t work. But rather than have this conversation take place in the shed, or come up with some organic reason for her to be elsewhere, the writers don’t bother to explain why this woman isn’t in her own bed at night.

Basically, the seams are showing. Every show — no matter how good — needs to cheat itself every once in a while. If the presence of a certain character would bring a particular story to a grinding halt, then there’s nothing wrong with keeping that character occupied elsewhere. It’s minor, and it’s totally acceptable.

However if you don’t come up with something else for that character to do, you’re leaving the plumbing exposed. It’s easy for the folks at home to see what you’re doing. You’re a lazy magician that doesn’t use sleight of hand at all; you just palm the coin and hope the audience isn’t paying attention.

I dwell on these things because I find them instructive as a writer. While any artist should surround himself or herself with great works, the truth is that great works are great because they don’t betray the work that went into them. In order to see what the gears look like, you need to look at something that fell apart. There’s value in the flawed machinery. You can learn a lot from watching a mechanism break down.

Anyway, Lynn comes in looking for her pillow and ALF replies that he’s resting his anus on it.

The three of them gather round and look at old photos of ALF.** He’s feeling sad, because the photos he found remind him of when he used to do exciting things in space. He shows them pictures of himself climbing Mount Floppy, and ascending Widowmaker Falls in a barrel. Now he sits on a stool in Willie’s garage, masturbating to a teenager.

This is another previously untapped vein of characterization for ALF. “For Your Eyes Only” charted adjacent territory, but that was mainly about how lonely ALF feels away from his home planet. This related — but definitely separate — aspect is a smart thing to explore.

Sure, he misses his home. He misses his friends. He misses Rhonda. But he also misses the adventure.

Really, think about that. It wasn’t just Melmac and Earth. ALF had full roam of the galaxy. He had personal, hands-on experience with planets and phenomena that we don’t even know exist. It’s easy to think that ALF spent his life punching a clock on a planet much like Earth, and certainly this show’s done relatively little to dissuade us from reaching that conclusion, but, really, even a mundane life in a society that’s mastered convenient, independent space travel has to beat a mundane life of being locked in the shed whenever company comes over.

ALF’s new life doesn’t just suck…it sucks on the heels of a life that was probably super awesome. So, yeah, that’s a pretty great angle for a story to tell.

The conversation segues nicely into some gentle ribbing at the expense of Willie’s own dull life, and that may actually be the most narratively organic opening I’ve ever seen on this show.

Seriously. We find something interesting about one character, talk about it for a bit, and then realize we can apply it just as easily to another character. That’s the kind of thing you can do when you actually build characters.

Again, it’s worth remembering that Willie’s not really a person…even by the standards of sitcom writing. He’s a Frankenstein’d mishmash of temporary characteristics that we get introduced to and which are never mentioned again. Each time we’re supposed to believe that these details are the things that define who he is, and each time they get supplanted by something else the following week. It’s not because Willie’s character is Protean — again, think Roger on American Dad!, where constantly changing characteristics are part of the joke — but because the writers can’t commit. They keep trying new things, but nothing sticks, so every week that Willie walks through that front door, we have no idea who he’s going to be.

Yet there is one — and maybe only one — characteristic of Willie’s that’s been consistent from the very first episode. And while there’s not likely to be much agreement about such a sloppily sketched character, I actually think it’s fair to assume that this particular characteristic is one everybody can agree on:

Willie is dull.

And this episode, for purposes beyond a joke, is going to explore that.

That’s good writing. You may have written yourself a character with only one consistent trait, but that doesn’t mean you can’t explore him. It just means that there’s only one angle you can take when you do it. It limits you, but it’s not a creative death sentence. Just look at all of those Simpsons episodes that took one-note characters and built a story around them.

Krusty, Moe, Mr. Burns, Apu, even Troy McClure. These characters were each built on a single joke…but by narrowing the focus and digging into that joke, the writers were able to flesh out the characters from within. None of them had to be fleshed out, mind you. They were — and are — secondary characters. So, why did they do it? Because they could.

Willie shouldn’t have to be treated like a secondary character in order to grant him life. He’s at the center of this show; you don’t need to set an episode aside to tell us who he is…you can tell us gradually, over the course of as many weeks as the show runs.

But, well, here we are. Desperate times, as they say, and since Jean and Reiss worked exactly this magic as eventual Simpsons showrunners, they just might be able to pull off the impossible, and humanize a character who has yet to act like a human.

This humanizing begins with Willie defending himself from the charge of being dull. While ALF and Lynn are clearly just giving him a hard time, Willie genuinely bristles at the suggestion. Which, clearly, is only because there’s truth to it.

This is when he tells them that when he was 17, he used to hop freight trains. He’d take them wherever they were going, all across the country, and do odd jobs for money. He even played the piano in bars, which ties nicely into the fact that we’ve seen him playing the piano and the keyboard before. This sub-detail manages to cement another trait for Willie, re-framing previously meaningless scenes so that they become retroactively character defining. And if you think I’m reading too much into that, wait for the next scene, which makes these intentions of “Night Train” very clear.

This train-hopping isn’t something Willie wanted his kids to find out, and ALF presses him about that. If he used to have so much fun riding the rails, why keep that a secret? ALF’s referring to keeping it a secret from Brian and Lynn, but it’s impossible not to hear this as a question of why it would also be kept from the audience.

The answer is that Willie wouldn’t want his own kids engaging in such dangerous behavior, and that actually ends up answering the audience question as well. Why don’t we know about it? Because Willie wouldn’t talk about such things in his home, which is pretty much the only place we’ve seen him. There’s a reason we’ve never heard this before, and it has to do with the context of the show, and also the conflict in question: Willie is dull, so he spends his time at home. Because he’s at home, he can’t share with us the fact that he used to not be dull. It works.

ALF, of course, presses him about why they wouldn’t want the kids engaging in dangerous behavior, and Willie sarcastically replies, “It’s just Kate laying down these arbitrary rules.”

It’s bitchy on Willie’s part. And God knows we’ve seen Willie be bitchy about Kate before. It’s tempered with just enough irony to turn the joke back on ALF for asking such a question in the first place, but there’s the ghost of real frustration in there. Keep that in mind, because, for once, the writers will, too.

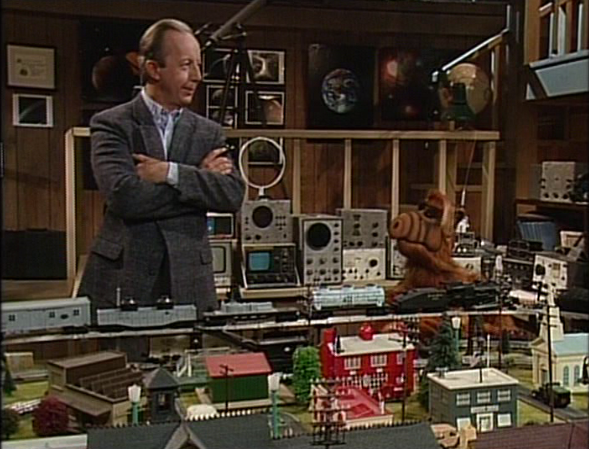

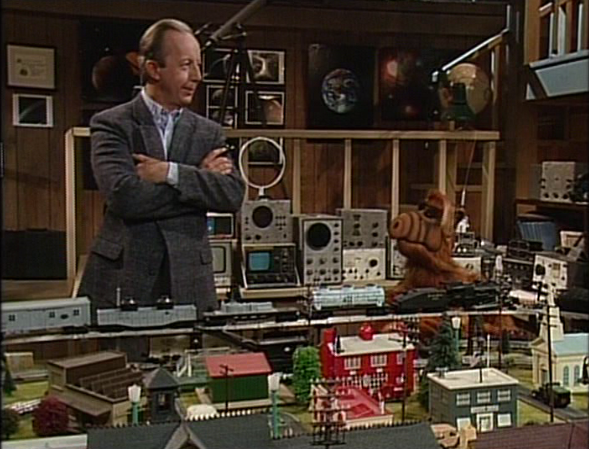

The next day, ALF is playing with the elaborate train set in the garage.

Remember the elaborate train set? You might not, because I’m not sure I’ve mentioned it before. After all, it’s not like it ever came into play. But it was there in the pilot, and at least one other episode (I think). And while it never really did anything but take up space, it existed in the universe of the Tanners.

Here, the writers dug back into this unexplored detail. They saw that it was there, they realized that they’d never done anything with it, and, all at once, they’ve given it meaning. Far, far more so than his mouse traps and rain gauges and ham radio, the train set tells us about who Willie is. It didn’t always…but it does now.

Why would he have spent so much time building this thing in the garage? Well, it’s because it’s meaningful to him. It’s a personal reminder of who he used to be. The episode doesn’t tell us this outright, but it’s easy to infer, especially considering how wistful Willie gets when he walks in on ALF playing with it.

He starts telling ALF about what it was like, and Willie’s nostalgia is palpable. It probably represents Max Wright’s best acting so far, but it’s not as though that was a very high bar to clear. He tells ALF that he hopped trains so often, in fact, that he even earned a nickname: Ol’ Cracky.

…no, it was Boxcar Willie. Which, actually, is exactly the nickname actual human beings might give to a guy named Willie who rode in boxcars. Yes, it’s another music reference in a show full of them, but this one works. It makes sense. It’s not labored; it’s a reference that exists in the show that would have probably also existed in real life. For ALF, this is an accomplishment worth celebrating.

ALF asks Willie about the kitchen car, which is a cute enough question, but here’s what really makes the moment stand out: Willie laughs.

They’re getting along. I’ll say that again, and I may even have it framed: ALF and Willie are getting along.

Why doesn’t this happen more often? ALF and Willie, without question, should be the central comic dynamic in the show. Alien / Earthling. Sponge / breadwinner. Freewheeler / uptight. Silly / serious. Naked / suit and tie.

They’re a classic Odd Couple pairing, and yet the show doesn’t seem to realize that. The fact that we also have a frustrated housewife, wide-eyed little boy, and high school girl living in the house should give rise to some nice side stories, but the heart of this show needs to be Willie and ALF.

There’s comic mileage there. And moments like this, Willie’s seemingly-sincere chuckle when ALF asks about the kitchen car, shows that Paul Fusco and Max Wright can actually have some chemistry.

The little I know about the inner-workings of ALF leads me to conclude that the antagonistic relationship between the two actors kept the writers from exploring the relationship between the two characters. And while I can respect that (actors are still human beings), I keep thinking about Red Dwarf, in which the two main actors also disliked each other…something the writers took full advantage of, as it allowed for the mutually-irritating relationship between Lister and Rimmer to feel right. They were actors, but they weren’t acting. The emotions were real, and as the rocky relationship between the two men softened into understanding and fondness in real life, the writers took advantage of that, as well, and stopped leaning on direct conflict in favor of group comedy.

Perhaps — and I’m only hypothesizing here — the fact that Chris Barrie and Craig Charles were made to act out their animosity on camera resulted in them realizing how silly it was. They came to respect each other, at least to some degree, because there was no reason not to. Sitcom as a form of public therapy, perhaps. In the case of ALF, the two actors didn’t like each other, so their interactions on camera were kept to a relative minimum. Not only did that stymie what should have been the richest comic relationship in the show, but it meant Fusco and Wright never had to come to grips with what babies they were being. By keeping them separated, the animosity was allowed to survive. Barrie and Charles continue to work together on Red Dwarf to this day. Wright and Fusco probably can’t even say each other’s names without dramatically spitting on the ground.

ALF then tries to convince Willie to take him to the train yard. He’s never seen a real train, and the stories have him excited. This is ALF getting to be a child…something I really like, and something the show should do more often.

When ALF buys a car and wrecks it, that’s not funny. When ALF wants a TV show to stay on the air so he hacks the ratings, that’s not funny. When ALF wants to see trains and begs a “parent” to take him, that’s wonderful.

He tries a few different things to get Willie to take him, culminating in the lie that he has 24 hours to live. Willie finally relents, and ALF, surprised, asks, “You bought that?”

Willie says, “Nah. I bought the second thing you said.”

Then ALF asks Willie to remind him what the second thing was again, so he can remember to use it in the future.

This is cute. It really is. These two are playing off of each other rather than bickering, and that works wonders. When Willie or Kate engage with ALF, he becomes a lot less irritating…even if he’s still (technically) demanding and selfish. It’s because when his sort of dickishness is one-sided, it comes off as a kind of verbal abuse. It’s unpleasant, and only rarely funny at all. When Willie and Kate are allowed to push back, it becomes a give and take, which cushions the blow substantially, and can even, as it does here, imbue the exchange with a kind of unexpected sweetness.

They take a wrong turn and end up on stage in a middle school play about…

…oh. Nevermind. That’s the trainyard.

Whatever. Teasing this show about its budget isn’t totally fair. I know I do it a lot, but that’s mainly because most episodes of ALF are fuckawful. “Night Train” might look a little ropey, but it’s trying, and I’ll absolutely give it credit for that.

srsly tho that set really does look like shit.

As soon as they get there, Willie starts nerding out about trains. He talks about how much they weigh, how fast they go, what they’ll do a penny left on the tracks, and it’s really nice. This makes sense; Willie is a nerd. Or should be. He’s got the look of one, and the periodic interests of one, but he never has the passion of one.

Think about it. This is a guy who used to spend all of his spare time poring over starcharts and broadcasting messages into space, seeking proof of intelligent life. Then a space alien crashes into his garage, so he tells it not to eat the cat, and goes to bed because he has work in the morning.

If alien life interested him so much, how come he hasn’t given a single shit about it since he’s started harboring living, breathing proof of its existence?

I’ll tell you why: because that’s not really something he was interested in. The writers thought he was. Maybe the actors thought he was. And the audience was supposed to believe he was. But based on what actually happens on the screen, and the fact that the show immediately ditched sci-fi hooey for a story in which ALF steals an old lady’s pizza, we can see that that wasn’t the case. It’s something we were told, but nothing that was really true.

Here, though, we’re told that Willie has a fondness for trains. Then Willie is at the train yard and he demonstrates that fondness for trains. It’s really not difficult, but what we’re told and what we see so rarely synch up on this show that when it does happen, it means something. It means the writers are paying attention. And then, all at once, I am, too.

Willie gets to be a nerd. He loves something very specific, and and we witness that love in action. It’s long-overdue, but welcome all the same.

Then there are some stupid jokes that actually get laughs because we’re invested in what’s happening. A train comes by and ALF wigs out because of how large and loud it is. “This makes the one you have look like a toy!” Next a guard comes by and Willie tells ALF to hide, but ALF isn’t concerned, because the guard has a seeing-eye dog. No, Willie says, it’s a doberman pinscher. This causes ALF to panic and say, “Don’t let it pinch me!”

See, this is why the high-water mark of good writing is important. You can have these groaners, and they can actually be welcome, because what they do is sort of remind the audience that they’re watching a silly show. Sure, there’s an alien squatting in a bush there, but when the writing is good we start to empathize with the characters. One of them remembers a long-gone pastime and starts missing it, which allows for an emotional connection with with those watching at home…most of whom undoubtedly have their own fond memories they wish they could relive.

That’s when the minor, silly jokes work best. They punctuate the emotion with release. They keep the heart from overtaking the episode and tipping it toward drama. It’s a chance to laugh along the way to the big climax, which could either be emotional or comic. They’re a way to maintain balance…a balance which necessitates care and attention on the part of the writing staff. It doesn’t happen automatically. It takes work.

Here, they’re investing the work. In other episodes, “Don’t let it pinch me!” might be some pointless line I’d forget the moment the studio audience of the undead stops laughing. Here it registers, because it serves a purpose. It’s a moment of release. I don’t laugh because it’s hilarious…I laugh because the episode worked to get me on its side, and I’m willing to play along. It’s demonstrated to me that I can trust its construction. It’s going somewhere. It promises me that much. The least I can do is climb aboard.

Speaking of which, they run from the guard and ALF jumps a train. Off-camera, because the midget was busy that week. Willie jumps in after after him. The logic of how ALF manages to hop into a moving train without difficulty doesn’t stick in the throat the way it did in “Baby, You Can Drive My Car,” when it was perfectly reasonable to wonder how he reached the pedals. Again, that’s because we’re along for this ride. We trust it, so we’re not asking questions. We’re following along.

This, again, is why good writing is so important. You can get away with a lot more when you’ve earned the respect of your audience. The best episodes might be full of illogical gaps just as the lousy ones are…but because we like the good episodes, those gaps don’t matter, and may not even register. Treat your audience like idiots, however, and all we will do is pick your show apart. Why wouldn’t we?

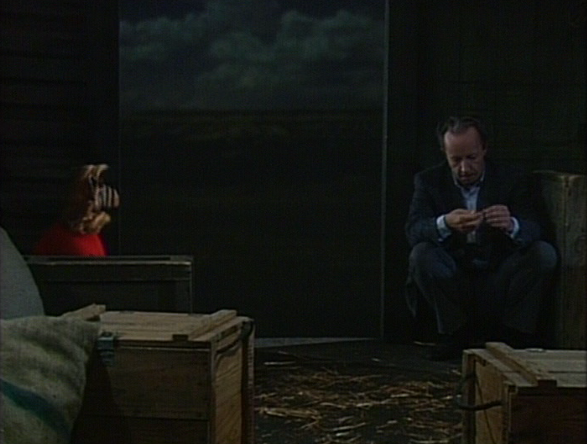

There’s a long period after the commercial where ALF and Willie sit in silence. The lack of dialogue holds just long enough that when ALF breaks it to ask, “Who do you think’s on Letterman tonight?” it’s a legitimately good laugh. Timing is everything.

With the silence broken, Willie unloads. He asks ALF what possessed him to get on the train. ALF asks, “Is ‘impetuosity’ a word?” Willie tells him it is. ALF then says, “Then I did it because I’m impetuosity.”

And that might be the best damned joke I’ve ever heard in this show. I’m not kidding. That’s 30 Rock-level stuff. Tracy Jordan and Liz Lemon could have had the exact same exchange. I’m genuinely impressed.

Of course, this is ALF. The feeling of being impressed is short lived, as a fuckin’ cartoon hobo comes out.

This is Gravel Gus. What with the human aspect of the show being handled pretty well so far, I actually kind of expected part of the moral of this episode to be that you can’t go back again. Things have changed. Maybe Willie had colorful boxcar adventures three decades ago, but now it’s fantasy. There’s no room for that lifestyle today.

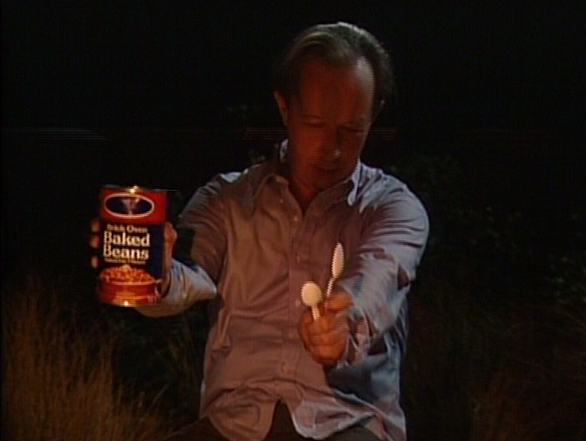

But, no. Gravel Gus is like any one of those hobos you see in old Warner Bros. cartoons. He’s got the wardrobe and the silly voice and the can of beans. So much for respecting the audience.

ALF hides behind a crate when Gravel Gus shuffles into view, but he can’t resist shouting excitedly when the hobo offers up some beans. Gravel Gus sees ALF and, of course, assumes he’s a kangaroo, at which point he leaps to his death.

…what?

Maybe if he thought ALF was a coyote or something, fine. But does the sight of a kangaroo cause people to flee in terror? Would you honestly throw yourself from a speeding train at the mere thought of one?

Oh well. That part was pretty fucking shitty, but at least we only had to spend thirty seconds of the journey with Gravel Gus.

It’s odd, though, how quickly he appears and disappears. Did he have a larger part in an earlier draft? Or were the writers fucking with me? “Oh, you were enjoying this one, Philip? Well…here’s Gravel Gus!!! …nah jk that guy died. We’re writing a good one this time.”

With an innocent man splattered on the tracks, a standard episode of ALF has reached its midpoint. Our two heroes complain about how uncomfortable and cold they are, and how hungry. Willie is surprised that ALF could be so quick to bitch about this stuff, since he used to climb space mountains and engage in cosmic derring-do before he started his new life, chained to Willie’s radiator.

But ALF admits that he never did those things. They were looking at novelty photographs that he’d had taken at a carnival.

When the guard arrived, ALF jumped onto the train not only to get away, but because Willie made it sound like a train ride would be fun and adventurous. That’s why he got excited over a can of beans. That’s why he started singing “The City of New Orleans” before Willie shut him up. For ALF, this wasn’t a chance to recapture the life he once had…it was a chance to live the life he wishes he’d had.

Wow. Complex motives. This is major, folks. These are almost — dare I say it? — characters.

ALF, the space alien with the galaxy at his fingertips, was actually jealous of Willie. They both might lead dull lives now, but at least Willie had some real excitement in his past. This was ALF’s chance to have some too.

That’s fucking wonderful.

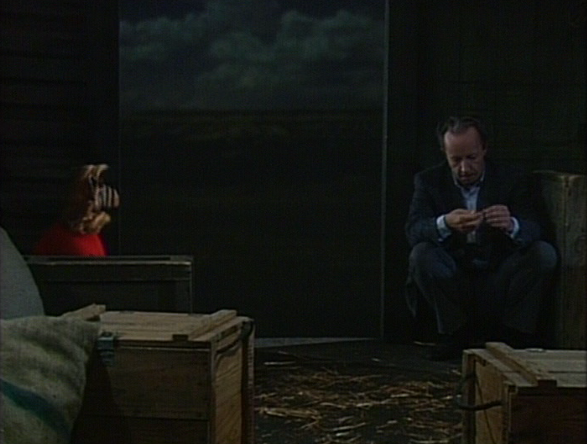

ALF’s honesty causes Willie to soften a bit, and they end up having an actual conversation. The dialogue isn’t great or anything…but it’s good. It feels real. These two are opening up to each other. The fact that they’re stuck in some room together is nothing new, but the fact that they’re conversing like human beings absolutely is.

They talk a bit about Melmac, and Willie actually asks him questions about it. Hey, remember when Willie was like totally so interested in alien life and stuff?? Kind of funny how he loved it so much but never thought to ASK THE FUCKING SPACE ALIEN WHAT SPACE IS LIKE

Anyway, he does it now. Better late than never, I guess.

ALF tells Willie that he’d just started dating Rhonda*** when his planet exploded. “Unlucky in love, unlucky in Armageddon.” It’s a great line, actually…one that reminds you of just how horrific ALF’s backstory really is. Mork still had Ork. Balki still had Mepos. ALF’s got nothing.

In order to emphasize this fact, the writers have ALF point out to Willie where Melmac used to be: “That spot up there. Where it looks like there should be a planet.”

Fuck me. That’s both effectively funny and effectively sad.

Willie spots a shooting star and tries to cheer ALF up by telling him to make a wish. ALF wishes he had his planet back.

Damn, kids. “Night Train” is pretty good for an episode about a stammering dipshit and his rapist puppet friend.

Later on it’s Willie’s turn to open up. Honestly, the fact that he used to ride the rails is enough characterization for me. What comes next is actually really nice, but almost unnecessary. And I like that. We’ve got some believable glimpse of a personality for the first time ever…but the writers decide to give us more. They’re on a hot streak, and a base hit isn’t enough for them. They’re going for a grand slam.

Willie tells ALF that he never thought he’d be married and settled down. Why? Because he didn’t want to be like his father.

Wes Anderson presents: The Life Cosmic with Gordon Shumway.

It’s not much background information, but it helps us to understand Willie. As much time as we’ve spent with Kate Sr. in person, we’ve heard all of jack shit about Willie’s parents. The fact that he didn’t get along with his father retroactively explains why that is. I can tell you from personal experience that the more strained your relationship with your father is, the less likely you are to volunteer any information…including whatever positive memories you might have.

This works.

ALF asks what Willie’s father was like, and Willie says that he was married with two kids**** in the suburbs. But Willie resented how dull and structured his father’s life was, and his impulsive adventure across America’s rail lines was a direct attempt to break away from that.

While traveling, he met a girl in Colorado and fell in love with her. No, it wasn’t Kate…it was Linda Evans. For those who don’t know, Linda Evans is probably best known for her regular roles on The Big Valley and Dynasty, but she also played a prostitute in Mystery Science Theater 3000 favorite Mitchell.

Notice an interesting parallel here?

In “Jump,” ALF‘s first attempt at defining Willie Tanner, we learned that Kate had an adventurous streak in her youth, and that she had some kind of romantic entanglement with a celebrity.

What do we learn in “Night Train”? That Willie had an adventurous streak in his youth, and that he had some kind of romantic entanglement with a celebrity.

“Jump” did a better job of fleshing out Kate than it did Willie, for exactly that reason. Because we learned about the things she did (running with the bulls, writing fiction, Joe Namath) we were able to draw reasonable conclusions about the kind of person she was.

We didn’t get any of that for Willie in that episode. Just a shot of a gorilla skydiving.

Here, they dust off that template, and align it properly this time. The execution is a lot different (thank fuckety fuck) but the kinds of details we’re getting are the same. It’s like somebody on-staff saw the same thing I did in that episode, and finally made the effort to center the character development where it originally should have been.

I don’t even mind it. I’m willing to accept that both of these people were once much more spontaneous than they are now, and while it’s a bit of a stretch to think that they were both involved with famous people before they met, both of these reveals work, and I’m willing to overlook the suspicious similarity.

Besides, it leads to Willie confirming that as adventurous as he once was, and as much as he got to jizz on Linda Evans’ boobies, Kate was the true love of his life. And that’s sweet. As nostalgic as he was for riding the rails and porking the woman who was in not one but two Kenny Rogers made-for-TV movies, he realizes that he’s happier where he is now than wherever he was then.

He tells ALF — and reminds himself — of why he’s glad he ended up where he is. His first Christmas with Kate. Lynn being born. Brian’s first words. A bit cliche, but 100% human. You get the sense Willie is remembering for the first time in a long time that he’s actually a pretty lucky guy.

Then ALF asks if he ever wishes that he didn’t crash his spaceship into his house.

Willie hesitates just long enough for us to get the idea, but he tells ALF, “Never.”

Then he puts his arm around him and that was fucking adorable.

See? This is chemistry. This is why Willie and ALF need to have the central relationship in the show. They’re funny. They’re honest. They get on each other’s nerves, but they also let their guard down. This script could actually be from an unproduced episode of The Odd Couple and I’d believe it. Only I’d have to wonder why Oscar Madison was reminiscing about his destroyed homeworld.

God. If this was the only episode of ALF I’d be convinced that if it had only been picked up for a series it could have been brilliant.

The short scene before the credits actually breaks format a bit. It’s a few minutes long, and it resolves the episode rather than leaving us with a quick gag.

It starts with Kate getting a phone call from Willie. We only hear her side of the conversation, but we learn that ALF and Willie are in Barstow.***** She says she’ll come get them, but before she hangs up there’s a short pause, and then we hear her say, “I’m glad I married you, too.”

Willie may be short with Kate. Willie might be downright obnoxious toward her at times. But in that moment, guys and gals, I genuinely believe they’re in love. And that’s a hell of a step forward.

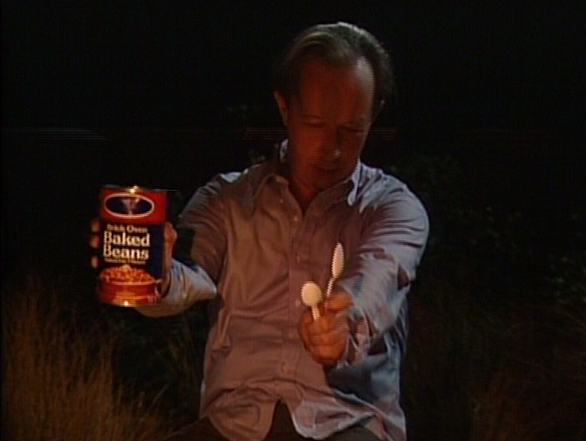

We then cut to Willie and ALF at a campfire. Willie says he found a minimart and called Kate, who will be there in a couple of hours.

While he says this he’s walking around really awkwardly, which stood out to me, but it turns out he was trying to hide a surprise for ALF behind his back:

He pulls out a can of beans and two spoons, and ALF is so happy he doesn’t even rape anyone. Then while Willie opens the can, he gently sings “The City of New Orleans” with his alien friend. The credits come up, and I love the fact that we didn’t end on a punchline. We ended on a note of vulnerable sweetness, and for an episode full of vulnerable sweetness on the parts of the two most problematic characters, that’s a hell of a breath of fresh air.

Season one had three good episodes by the time it ended. Season two now has three as well, and it’s not even halfway done. This might end up representing a step up in quality after all. And, hey, even if it doesn’t…I’m glad we have this one. “Night Train” wasn’t just good; it suggests that ALF as a whole had everything it needed to be a great show. It wasn’t…but all of the components were there. “Night Train” is a welcome taste of what could have been.

So, who is Willie Tanner?

I still don’t know, but I hope it’s this guy, because I’d like to see a lot more of him.

I really hope he gets a show of his own one day.

MELMAC FACTS: The currency on Melmac was the Wernick, which was worth $10 American. Dating on Melmac was called “Taking a Girl to Dinner and a Movie.” Telephones were called “Those Plastic Things on the Counter that Ring.”

—–

* Funnily enough, “Jump” was the ninth episode of season one, and now we’re getting our next exploration of Willie in episode nine of season two.

** “Wedding Bell Blues” kinda sucked, but I do like the red-backed photographs it introduced into ALF’s mythology. It’s a tiny detail, but the fact that they’re red suggests a different photographic process and / or technology from what we know on Earth, and I like that. It’s the kind of unspoken detail you might get from a show that cared.

*** “Help Me, Rhonda” established that they never actually dated…their first date was supposed to happen the night Melmac exploded. But, again, this is the kind of thing you don’t worry about when you’re actually enjoying the show. That’s why it gets a footnote and not a FIFTEEN HUNDRED WORD SCREED

**** Is this true? In “La Cuckaracha,” Willie mentions having a brother named Rodney. But I know in season four, we meet his brother Neal. So that’s three kids…unless Neal turns out to be adopted or something. In fact, I kind of hope he does, because I’d hate to imagine the man whose semen could give rise to both Max Wright and Jim J. Bullock.

***** Google Maps puts the journey from LA to Barstow by train at three hours, forty-one minutes. While the schedules have changed (I’m sure) since this episode aired, it’s the Southwest Chief that now makes this journey daily, passing through LA at 6:15 in the evening and Barstow at 9:56, which matches up pretty darned well with what we see in the episode. Incidentally, Kate saying she’ll be there in a “couple of hours” is also accurate, as the driving time between those two cities is about an hour and forty-four minutes. Fucking hell, writing staff. When did you start doing research?