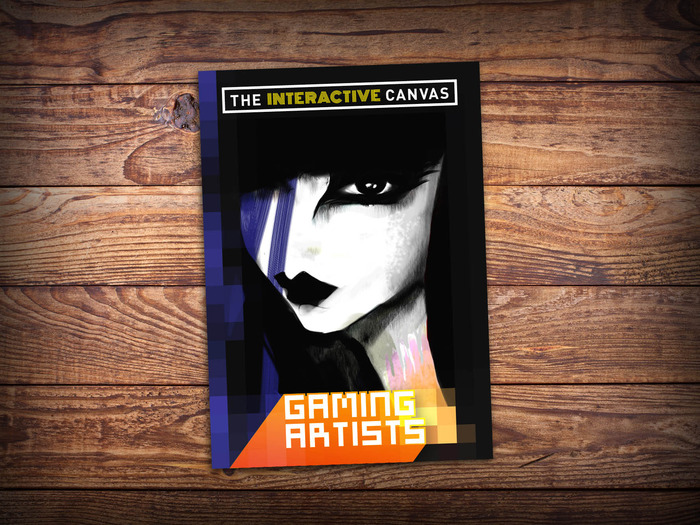

About a month ago I wrote about a project called The Interactive Canvas. At the time it was a Kickstarter hopeful, with author Matt Sainsbury (of Digitally Downloaded) hoping that people would pledge enough money for him to assemble the games industry interview collection of his dreams.

Typically Kickstarter success is measured in terms of funds: if you don’t meet your goal, you’ve failed. If you have met your goal, you’ve succeeded. If you’ve exceeded your goal, you turn cartwheels for several weeks straight.

In the case of The Interactive Canvas, however, success took quite a different form: Matt got the news that a traditional publisher was interested in his book, and he wouldn’t have to crowdfund it after all. The Kickstarter came down, and The Interactive Canvas was fast-tracked to becoming a reality. Hot on the heels of this good news, Matt Sainsbury sat down to graciously respond to my stream of nonsense.

1) In exactly 21 words, what is your intention with The Interactive Canvas?

To provide a definitive resource on the topic of art games, through interviews with some of the industry’s greatest creative minds.

(That was more restrictive than Twitter, you evil man!)

2) What’s the philosophy behind the book? What goes into selecting what you’ll cover, and how you’ll cover it?

The Interactive Canvas is taking my standard journalist process — interview, interview and interview some more — and building a book around it. It’s the people that make games that best know the creative process behind making games, so I do believe that letting them talk about themselves, their backgrounds and their approach to game design will be the best way to show the broader arts community that games are really no different to film or literature now.

As for how I select what to cover, I play dozens of games, sometimes in one week, so, while it would be impossible to cover every artistic game, I have played a very broad range of very artistic games. Securing interviews with the developers of those was my first priority.

3) If you could change one thing about the games industry, what would it be?

It needs greater input from women. The number of women who are game directors (ie: the top of the industry’s creativity) is small — certainly smaller than in any other creative industry. It would be truly great if this industry could move past the boy’s club, and the creative ideas of women could be given the same prominence as their male counterparts.

4) If you could change one thing about gaming community / fans, what would that be?

It would be really lovely of the gaming community could stop harassing game developers for their creative ideas. Mass Effect 3‘s ending and Dante’s “new look” in DMC are just two examples, but there are many more where, the moment a game developer does something that people don’t agree with or don’t understand, those same people take to Twitter, forums, Metacritic and more to harass and threaten harm to the developer. How can we have a creative industry for artists to work with when said artists have a good reason to be frightened to be creative?

5) You’ve referred to The Interactive Canvas as the first book in a series. In what ways would you like to see the series evolve as it progresses?

In my dreams this book will be an annual publication that will continue to track the development of the games industry as a creative medium through more interviews with more developers. I would be over the moon if, ten years down the track, people have access to ten editions of this book, and they can refer back to the first and second book to see the progress of the ideas and philosophy that drive game developers and the games they make.

6) You’ve traveled through time, and you’re handed a pre-release copy of Super Mario Bros. 3. It’s your job to change it in some way to make it better than the game we know today. What do you change? And don’t give me that “It’s already perfect” horsecrap.

I add Chocobos. Every game gets better with Chocobos.

7) What’s your favorite Bob Dylan song?

“One Headlight” by The Wallflowers. I’m the only person in the world that prefers Bob Dylan’s son’s music, but there you go.

8) You’ve got a lot of great interviewees lined up for The Interactive Canvas, but if you could rub a lamp and have any three people in the industry agree to an interview, who would you choose?

David Cage: I interviewed him once before and the guy thinks about games more deeply than anyone else I’ve ever met.

Shigeru Miyamoto: It’s impossible to discuss games on any meaningful level without considering the impact that this man has had on games.

Yuko Taro: People might not know this name, but this is the man that made Nier. Nier is pure art.

9) Discussions about video games seem to get heated rather more quickly than discussions about literature or even music. Why do you think that is?

Discussions about video games get heated quickly, but, more importantly, they get heated over the silliest of topics. “My console is better than your console,” or “I disagree with you so you’re stupid.” It’s quite childish really and I do think that the reason that literature and music have more interesting, civil conversations is because it’s possible to find places to have discussions on a mature level. With the games industry it’s impossible to avoid the immaturity.

10) What is the second best gaming system ever made?

The PlayStation 3. I like my consoles handheld so the fact that the PS3 isn’t portable is the only reason why the DS will always be the better console in my mind. Both consoles have a shedload of JRPGs on them, and this really is all I care about when determining the quality of a console.

11) Why Kickstarter? What sort of challenges did you face working with that platform?

Because Kickstarter was to be the only way I could raise the money to self-fund the publishing of the book. It’s a marketing nightmare to try and get people to support a Kickstarter campaign; I must have spent 15 hours a day working on that thing while it was live, but it worked — without the Kickstarter I would never have got the publisher.

12) Peach or Rosalina?

Peach is a hopeless character, so Rosalina.

13) While it’s debatable whether or not the Ouya failed, it’s obvious that it didn’t meet expectations. What do you think happened?

I think people had unrealistic expectations of Ouya. People saw that it raised a few million dollars via Kickstarter and overshot its target by a massive margin, but forgot to remember that a console like the Sony, Microsoft and Nintendo devices cost more than a few million dollars to make and support. Ouya was always going to be a “B-Grade” console. The fact people were disappointed by this just shows how little people understand about how the spreadsheet side of the industry works.

14) What classic novel deserves a video game adaptation?

The Big Sleep. But I worry that Activision would buy the rights and turn it into a linear FPS with a cover system and dog companion.

15) You describe The Interactive Canvas as a coffee table book. On a scale from 1 – 10, how offended would you be if somebody kept it on their kitchen table instead?

10. The Kitchen is where you put cook books. Does it look like I’m going to have a recipe for my world famous lemon tart in there? Actually, that’s not such a bad idea…

16) It’s a tired question. I don’t care. Are video games, today, as they currently stand, art?

Yes. But people don’t treat games like art. They say “oh, games are art because look at how pretty they are,” completely misunderstand that a game’s graphics are not what makes it a work of art, and then go back to their arguments about how Call of Duty is better than Battlefield.

If games are to be legitimised as works of art in culture, then people need to start having discussions about games as art. This means philosophy. This means sociology, and psychology. This means feminism — without the writer then being targeted by threats of rape. Games will only truly be “art” when the conversations around games grows the heck up.

17) Your tastes seem to gravitate toward games with a traditionally Japanese flair. Why do you think that resonates more strongly with you than what you see in Western games? Or does it?

Japanese games tend to have a stronger grasp on the idea of “fun.” I look at Western games and I see two things absolutely dominate: sports games, and extremely violent games. The former is fine if you’re a fan of the sport, the latter is visceral. But where’s the oddball humour? The variety of experiences? The silly sexuality? The surrealism? The abstraction?

I generalise, of course, but the western games industry tends to take itself very seriously, while the Japanese games industry has Hidetaka Suehiro and Goichi Suda. And, somewhat ironically, because the likes of Suda are so off-the-wall and weirdly creative, his work has far more artistic merit than the Western developers that seem to be more interested in competing with Michael Bay.

18) If you could have complete creative control over a new game in any franchise, which would you choose? What would the game be like?

Not so much a franchise, I’d say, but rather a license – the Warhammer franchise has been done dreadfully for 15 years, or however long it’s been since Warhammer: Dark Omen was released. I would take that license and build a slow-paced strategy RTS that focuses heavily on the strategy side of things. You know, like how the actual tabletop game is.

19) Most disappointing game purchase or rental ever. Go.

Any modern game that has the words “Star Trek” on the cover. Seriously, how can developers mess up that franchise when they literally have decades of lore and an entire universe to play with? Mass Effect proved galactic character-based narratives can work in games. Star Trek developers have no excuse.

20) You’re trapped forever in any video game. Which is it?

Atelier Meruru: The Alchemist of Arland. Because Meruru.

BONUS: Say anything to our readers that you would like to say that hasn’t been covered above.

The best way to enjoy a good game is with a six pack or ten of beer.

I’d like to thank Matt for taking the time to answer my moderately-relevant questions. I’m sure that as publication dates are set I’ll be talking about it again, so keep an eye out here and on Digitally Downloaded.